Mental health professionals may struggle to implement their own self-care. The culture of medicine has historically valued the ideals of self-sacrifice and perfectionism. As a result, psychiatrists and psychologists frequently report feeling guilty or self-indulgent when they take the time and effort to enhance their own wellness and quality of life. Professionals with mental disorders, substance-related conditions, or behavioral problems, in particular, are exposed to distinct and difficult stresses.

Appropriate self-consideration is respectful of one’s patients and oneself and essential for competent practice. To be effective, clinicians must be energetic, connected to others, and knowledgeable about preventive health and self-care. The fields of psychiatry and psychology have much to contribute regarding wellness, even as psychiatrists and psychologists face unique threats to well-being while they help others to bear considerable trauma, distress, and suffering.

This book was written for psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health professionals who care for patients across a full range of practice settings. Information has been included that is applicable throughout the professional life span, including for students and trainees. For reasons of brevity and readability, the text focuses primarily on psychiatrists and psychologists. However, the intention is to be inclusive of all mental health professionals at any level of training. The motivation behind this book is to offer inspiration, support, and practical strategies that can be employed by psychiatrists, psychologists, mental health clinicians, and trainees to advance professional and personal well-being.

Historical Roots of Wellness for Physicians

Although wellness has become an increasingly popular construct in contemporary life, the concept of caring for the self has deep roots in ancient philosophy, including in the practices of Ayurveda as well as ancient Greek and traditional Chinese medicine. The emergence of such fields as osteopathy, homeopathy, naturopathy, and chiropractic in the nineteenth century further set the stage for modern medicine’s increasing acknowledgment that mental and spiritual well-being support physical health. As the concept of taking care of wellness (as opposed to illness) became even more mainstream at the end of the twentieth century, businesses began to incorporate wellness programming into their employee benefits. Today, it is increasingly common to discuss issues of professional well-being across a wide range of disciplines.

In parallel with the growing focus on wellness in the general population, important historical movements in medicine paved the way for drastic change in thinking about the health of doctors themselves. The transition from seeing doctors as individuals with godlike powers to seeing doctors as human beings in need of support and caregiving has taken a long time and has been met with considerable resistance. Yet the mind-set change has had critical benefits for psychiatrists, psychologists, and patients alike.

Many of the barriers to acknowledging the importance of physician wellness have come from inside the field of medicine itself, driven by the sometimes fiercely held myth that to be a good doctor one must be superhuman. Aspects of medical training and practice reinforce this perfectionistic attitude, for instance, by creating training schedules that normalize unsafe sleep deprivation and medical licensure application questions about prior mental health treatment.

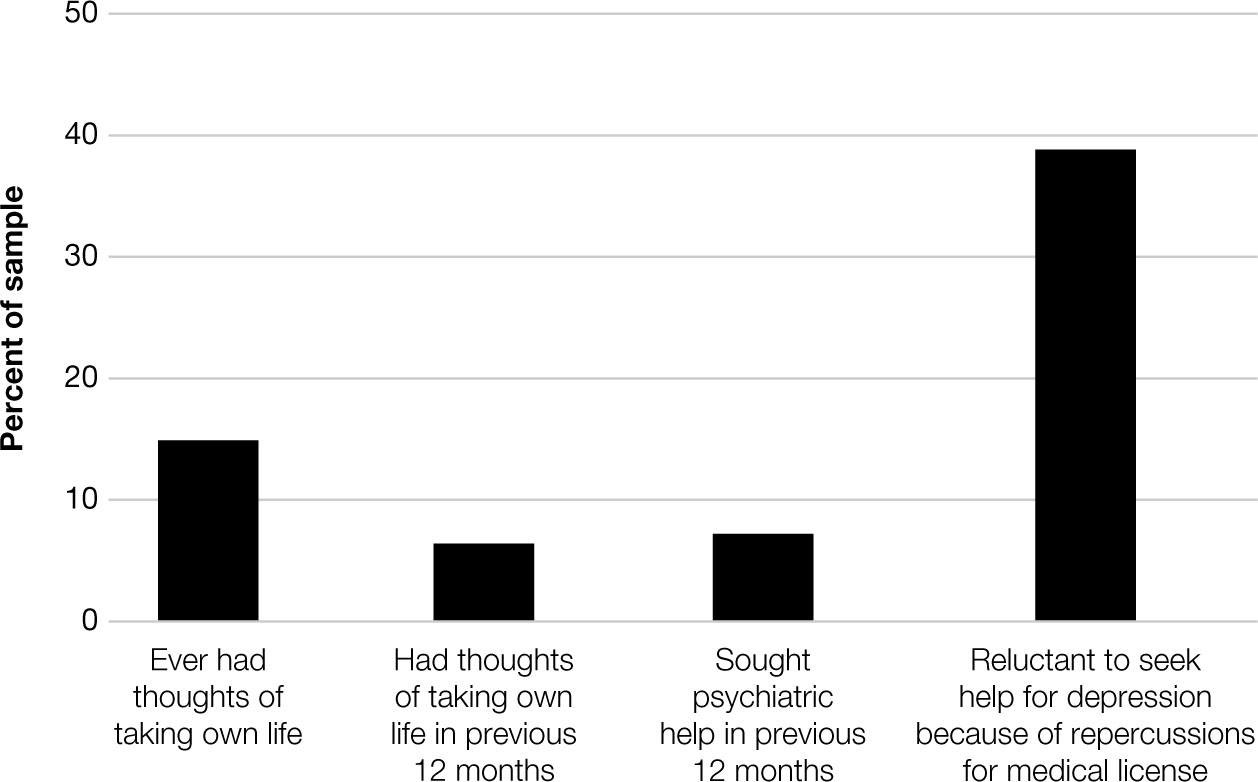

Figure 1–1 depicts a striking reluctance to seek mental health care among American surgeons, attributed largely to fears about potential medical licensure repercussions (

Shanafelt et al. 2011).

Trainees and practicing physicians may even neglect their own basic medical care (

Dunn et al. 2009;

Gross et al. 2000), perhaps because of time pressure or because of concerns about confidentiality (

Roberts et al. 2005). The message medical students receive tends to frame excellent patient care as potentially competing with good self-care. For example, the

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (2018) professionalism guidance promotes “responsiveness to patient needs that supersedes self-interest” (p. 18), suggesting that self-care should be secondary, an idea that has deep historical roots in medicine (

Trockel 2019).

In spite of these strong messages, powerful counterexamples have gradually begun to undermine the problematic view of the infallible doctor and suggest that the humanity of psychiatrists and psychologists can also be viewed as a potential source of strength. In part, this mind shift occurred because of individual physicians who wrote about their own illnesses and how the experience as patients made them more compassionate. In a compelling lecture titled “Arrogance,” Franz Ingelfinger described the poignant experience of working as a doctor who eventually contracted a disease in which he was an expert. He outlined the confusion his family felt without guidance from an authoritative physician in whom they could place their trust. In the following provocative statement, he imagined the benefits of restricting the practice of medicine to individuals who had been patients themselves.

One might suggest, of course, that only those who have been hospitalized during their adolescent or adult years be admitted to medical school. Such a practice would not only increase the number of empathic doctors; it would also permit the whole elaborate system of medical-school admissions to be jettisoned. (

Ingelfinger 1980, p. 1511)

After living through a significant medical illness, many physicians reflect on the ways in which they have treated patients in the past and wish they had done better. It is particularly striking that Ingelfinger noted in 1980 that the already growing pressures of efficient practice and computerized medical records were making personal relationships with patients, so necessary for effective care in his view, quite difficult. He concluded that the personal experiences of physicians inform their empathic practice. His writing had major influence on a generation of physicians struggling to reconcile their real-life experiences with the “good doctor” ideal.

System-level responsibility for sick doctors has been another galvanizing issue in the history of physician wellness. Many people believe that with all the self-sacrifice doctors commit for the sake of patient care, their institutions owe them, at a minimum, decent health coverage. Doctors who risk contracting serious illness in the line of duty provide an extreme example of this important issue. For instance, the case of Dr. Hacib Aoun, who in 1983 contracted HIV from a needlestick and was ostracized by his colleagues and dismissed from his hospital employment, sparked outrage about the treatment of sick physicians. In a New York Times article, Dr. Aoun described his poor treatment by colleagues and by his employer.

“It is hard enough to live with the nightmare of AIDS, especially with a wife and a small child,” Dr. Aoun said. “But to hear colleagues drop innuendos and issue slanderous comments about my private life and hear that the institution you committed yourself to will not help—that is too much.” (

Hiltsmarch 1990)

This case, and other similar experiences of stigma and inadequate care for physicians, prompted overdue improvements in institutional policy for injured doctors and, importantly, set the stage for more widespread physician health programs.

Inspired by stories like those of Franz Ingelfinger and Hacib Aoun as well as by the deeply personal experience of giving birth to her first child as a medical student, one of the authors (L.W.R.) began studying the health-related experiences of medical students and residents. This research revealed the tremendous stress associated with students or residents having any kind of health care need while in training. Students struggled with time demands, embarrassment, worries about access or costs of care, and awkwardness or vulnerability associated with the dual role of learner and patient, especially when seeking care in a training setting or from health care professionals who also served as teaching attendings. Students went to great lengths to obtain prescriptions from colleagues, mostly residents, “off the record.” It became apparent, too, that the experience of being a patient while in training had a profound formative impact: there was a great deal more to learn about the importance of compassion, competence, and self-advocacy than any book could teach.

In interviewing other medical students across the country, it became clear that many medical schools did not require comprehensive health insurance, an issue that persists today, particularly for mental health and addiction treatment. Students at some institutions were extremely worried about their health, about becoming ill, about their ability to obtain health care, and about adverse repercussions for their careers should it be known that they needed, or sought, health services. These conversations prompted the first multi-institutional study of medical student health care in the United States (

Roberts et al. 2000).

More than 1,000 medical students at nine medical schools participated in this initial survey project (52% response rate, with response rates varying from 20% to 87% by school) (

Roberts et al. 2000,

2001). Nearly all students—93% women and 87% men—in the study had health care needs. Most students had deferred or avoided necessary health care because of confidentiality, cost, and time constraints. Students, especially women and clinical-level students, strongly preferred the option for care outside of the training institution. Students expressed concern that they would experience academic jeopardy, such as lower grades from supervisors or a negative letter from the dean’s office for residency, particularly for stigmatizing health issues. These concerns were greater for women and for students identifying as members of an underrepresented minority. The narratives provided by respondents—about their own or their loved ones’ illnesses—were extraordinarily moving.

Interestingly, in the 1990s, only a limited set of medical education journals and psychiatry journals were willing to publish papers on the topic of medical student and physician wellness. Viewing the topic as unimportant or, perhaps, as self-important, it was difficult to persuade most medical editors and peer reviewers of the salience and impact of the health and health practices of physicians and physicians-in-training.

Thus, another set of historical barriers to acknowledging the importance of physician wellness is the perception that doctors are a highly privileged group. In the context of the vast range of human suffering, it seemed self-centered to focus on the well-being of these “elites.” Today, an emerging science of well-being—across fields of medicine, psychology, ethics, and organizational management—supports the idea that self-care is not selfish or overly indulgent but is critical for providing effective care (

Baker 2003;

Menon and Trockel 2019). In fact, the practitioner’s state of mind has tremendous influence on medical decision-making. Therefore, cultivating the emotional literacy and mindfulness of psychiatrists and psychologists can help ensure that decisions are made after considering all relevant medical and psychological/contextual evidence. One example of this approach has been called

mindful practice (

Epstein 1999), which can help physicians act with compassion, solve difficult problems, and cope with emotional experiences that arise during practice.

In direct contrast to the problematic ideal of the superhuman doctor, a new image of health professionals is now emerging that is focused on improving wellness for both patients and physicians through common humanity and self-compassion (

Horowitz 2019;

Trockel 2019). Self-compassion means practicing mindfully and with kindness, not just with others, but with one’s self as well (

Neff and Germer 2013). The self-compassionate approach to physician wellness has taken many decades to emerge, but it offers great promise as an authentic way to move forward for both healthier patients and health care professionals.

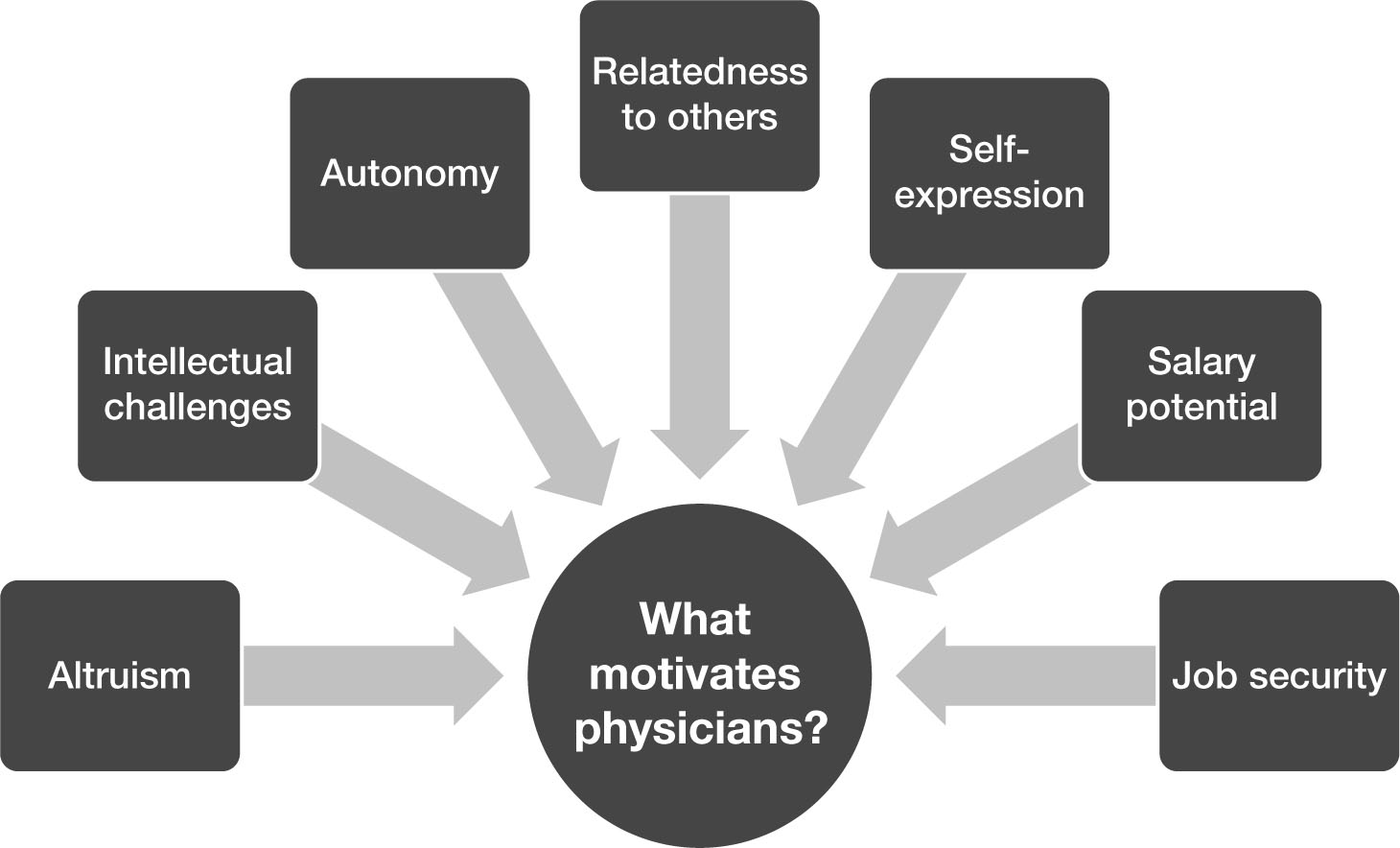

From Avoiding Professional Burnout to Enhancing Professional Engagement

Burnout was first described in the 1970s to capture the experience of therapists who were feeling mentally and physically depleted and no longer functioning effectively (

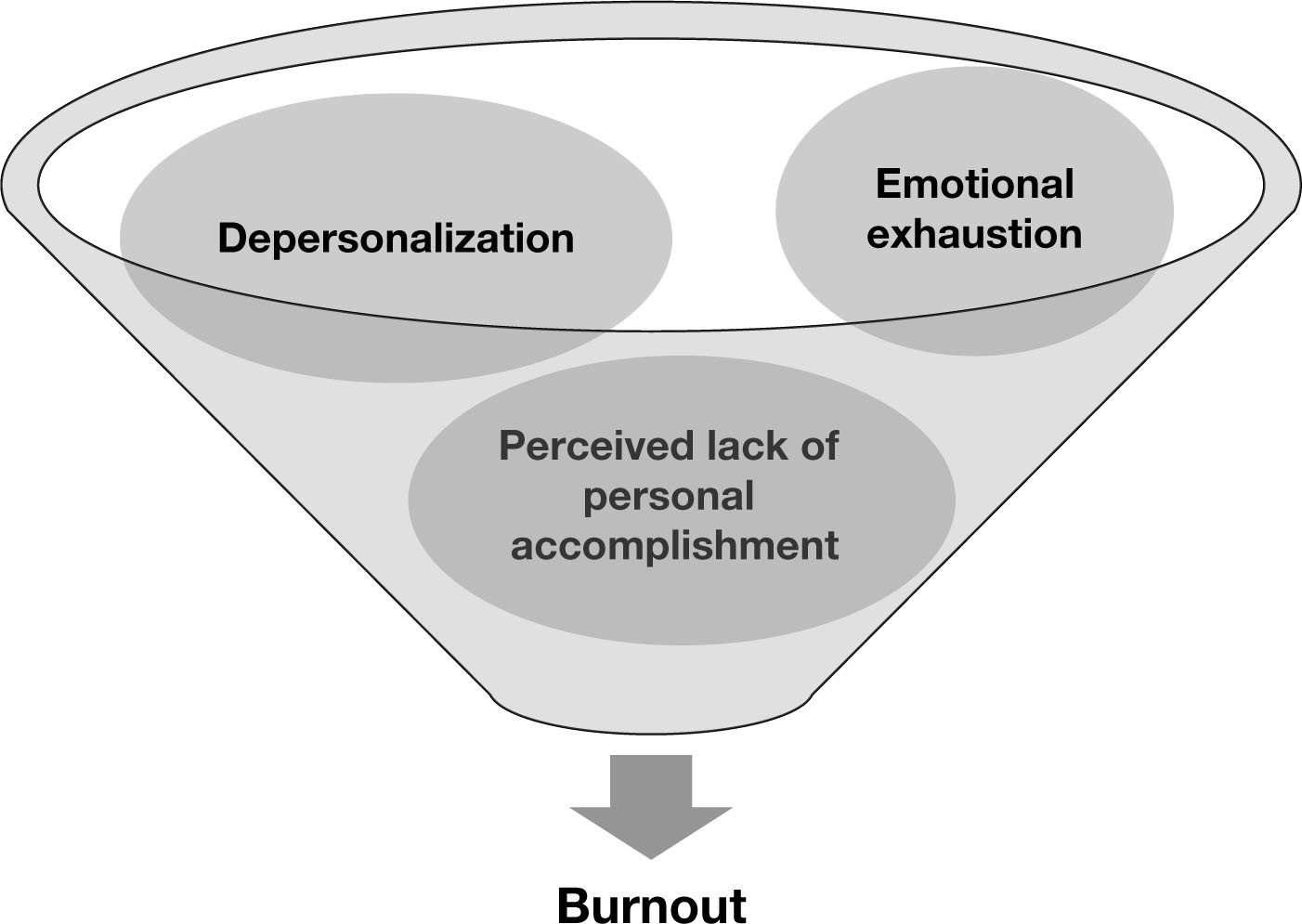

Schaufeli et al. 2009). As the study of this phenomenon has progressed, burnout has come to be known as a syndrome involving three components: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and perceived lack of personal accomplishment (

Maslach and Jackson 1981) (

Figure 1–2).

As the economies of many nations have shifted toward service sector jobs, burnout has emerged as a topic of great importance (

Schaufeli et al. 2009). The risk of burnout increases when workload is excessive and workers have minimal control or inadequate rewards. Conflicting values, perceived inequities, and poor interpersonal communication in the workplace are also contributors (

Leiter and Maslach 1999). Thousands of studies have now been published on the topic of burnout, and the World Health Organization has classified burnout in ICD-11 as a syndrome tied to “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” (

World Health Organization 2018). Over the years, the study of professional burnout has contributed greatly to the understanding of factors that promote, and also detract from, professional fulfillment and life satisfaction.

There are also legitimate concerns that the emphasis on the burnout construct can overshadow several critical wellness issues. First, the construct of burnout may be used to describe a wide range of symptoms that warrant differential treatment. The seriousness of clinical depression or suicidality, for example, can be obscured by the use of such a broad term. Second, defining a negative outcome like burnout provides inadequate guidance about what optimal functioning should look like. The goal of avoiding burnout is now seen as just a small component of a more important positive objective: enhancing professional engagement. Defined in contrast to the burnout syndrome,

engagement is evidenced by high energy, strong involvement, and increased sense of personal accomplishment (

MacKinnon and Murray 2018). The positive psychology movement (

Seligman et al. 2005) has further informed this transition from an emphasis on deficits and problems in the workplace toward exploration of opportunities for personal growth through meaningful work. Finally, the emphasis on clinician burnout can be criticized for placing implicit blame on the individual clinician, when, often, system-level drivers are major contributors to the prevalence of burnout. Improving clinician engagement and wellness (with associated decreases in burnout) will require a mind-set shift across many aspects of practice, ideally starting with early training experiences (

Eckleberry-Hunt et al. 2009).

The Professional Fulfillment Index (PFI), proposed by one of the authors (L.W.R.) along with colleagues, was created to assess dimensions of well-being among health professionals in a brief but more positive and balanced manner than other instruments that focus primarily on negative feelings toward work (

Trockel et al. 2018). The PFI seeks to evaluate variables that are relevant to physicians, measure change in response to workplace interventions, and uncover positive (fulfillment) and negative (burnout) aspects of health professionals’ work. The PFI underwent testing and was found to correlate with existing measures of burnout, although it includes additional domains, such as experience with making mistakes and evolving feelings and attitudes over time. Initial empirical work with the PFI suggests that it may provide a valid and reliable new methodology to advance the field of physician well-being. Findings that derive from the use of the PFI may also help to determine whether efforts to strengthen individual well-being and to introduce systemic interventions make a constructive difference.

Costs of Clinician Burnout

One major reason that physician well-being matters is the relationship between psychiatrists’ and psychologists’ well-being and the quality of patient care. Evidence suggests that physician burnout is associated with more medical errors (

Shanafelt et al. 2010;

West et al. 2009). Studies of psychotherapists have also indicated that burnout is associated with lower quality of care (

Lee et al. 2011;

McCarthy and Frieze 1999). The depersonalization psychiatrists and psychologists may feel when experiencing burnout also diminishes capacities of empathy and conscientiousness, which are critical when caring for the mentally ill. Mismanagement of personal boundary issues can also compromise quality of patient care. For instance, a clinician who lacks close personal connections outside the workplace may be more vulnerable to engaging in inappropriate relationships with patients or colleagues.

Studies show that doctors are also more likely to recommend preventive health care strategies that they themselves actually use (

Frank et al. 2013). Psychiatrists’ and psychologists’ practice of healthy behaviors may actually be one of the strongest predictors of whether they emphasize prevention with patients (

Frank et al. 2000;

Shahar et al. 2009), with data coming from diverse areas ranging from exercise to smoking cessation (

Abramson et al. 2000;

Howe and Monin 2017;

Pipe et al. 2009). What this literature suggests is that the patients of doctors who practice poor self-care likely receive less guidance regarding health-promoting behaviors. In contrast, efforts to improve clinician health could have important downstream effects on patients’ health.

Burnout and compromised well-being can also have significant business costs for organizations (as discussed in detail in Chapter 3, “Burnout and Clinician Mental Health,” and Chapter 7, “Legal and Ethical Issues in the Context of Impairment and Recovery”). Across fields, when a psychiatrist or psychologist leaves the profession, the cost of replacing that individual in the workforce is significant. When psychiatrists and psychologists work with reduced efficiency, or call in sick frequently, the organizations they work for suffer. Burnout in mental health care can be especially problematic because of the relational nature of treatment (

Lim et al. 2010).

Finally, the well-being of mental health care professionals can be seen as an ethical issue. First, self-care can be considered an ethical imperative related to competence (

Wise et al. 2012). Psychiatrists and psychologists have an obligation to practice within the boundaries of competence, including seeking medical and mental health care for themselves when needed. In addition, mental health care professionals have a human right to strive for health and wellness, the same objective they pursue so passionately for their patients. As the medical field has increasingly embraced the importance of preventive health care strategies for patients, there is greater appreciation of the important role that prevention plays in promoting physician health as well. When psychiatrists and psychologists know about the suffering of their colleagues and trainees, they have an obligation to help. Taking steps to improve their wellness, whether small or large, is the right thing to do for the sake of patients, for the sake of colleagues, and for the sake of psychiatrists, psychologists, and future generations.

Individual and System-Level Interventions

In this book, we review a wide range of strategies for enhancing clinician well-being. These strategies include both system supports that can be put in place and practical approaches that individual psychiatrists and psychologists can employ in support of their own wellness. Because of the growing recognition that burnout is a symptom of organizational problems, rather than individual physician weakness (

MacKinnon and Murray 2018), many types of system-level interventions have been proposed. For instance, workload and schedule adjustments, mentorship programs, and decision-making processes that allow for input from staff at all levels of the organization may help reduce burnout (

Panagioti et al. 2017). In addition, a wide variety of innovative methods and programs have been proposed and tested to enhance system health and clinician engagement. These include changes in the way psychiatrists and psychologists document care, increased use of technology in treatment, regular opportunities for professionals to discuss wellness issues with peers, and leadership training programs. System-level interventions are discussed in detail in Chapter 6 (“Systems and Supports for Clinician Wellness”).

For individual health care professionals, a wealth of practices can enhance well-being. In the final chapters of the book, we review down-to-earth advice for professionals seeking to enhance their own well-being. For instance, many physicians find that deliberately scheduling healthy activities helps them stay accountable for their own self-care. Burnout may make psychiatrists and psychologists more vulnerable to depression. Likewise, depression may make a person more vulnerable to burnout. Research has suggested that healthy activities, such as regular exercise, can help protect against these negative outcomes (

Toker and Biron 2012). Work on meaningful projects also helps, including making a clear list of personal and professional priorities and feeling comfortable enough to say no to opportunities that do not advance worthy and personal goals. Routine medical care and mental health treatment as needed are critical for healthy functioning. Vacation and time for social connections also feed a full life. Exposure to nature helps many people recharge and combat mental drain experienced by overwork or stress (

Berto 2014). Self-compassion is also critical so that real challenges can be acknowledged and addressed without harmful self-sacrifice.

Although mentorship and close connections with colleagues are critical for all professionals, the more isolated the psychiatrist or psychologist is during work, the more important strong mentorship relationships likely will be. Individuals in private practice must be uniquely responsible for their own self-care and burnout prevention (

Lee et al. 2011) and must often take the initiative to self-evaluate and seek peer consultation and supervision as needed to perform patient care with competence. Mentoring is known to reduce the risk of burnout in academic faculty members (

Van Emmerik 2004). In psychology, approximately two-thirds of Ph.D. students report having a mentor; the figure is lower for Psy.D. students (

Clark et al. 2000). The low rates are particularly concerning given that mentor relationships established in graduate school often form the basis for mentoring relationships in early-career professionals, either because the mentor continues to support the individual after graduation or because the mentor is instrumental in connecting the individual with another important mentor relationship. Institutional recognition of faculty who excel at providing such support should be seriously considered as a system-level intervention to help incentivize staff to perform this critical role (

Johnson et al. 2000).

Special Issues for Students and Trainees

A large body of evidence suggests that trainees and professionals in the earliest stages of their careers may be particularly vulnerable to burnout (

Baker 2003). Young age is one of the factors most consistently associated with burnout (

Lim et al. 2010), with multiple previous studies showing that older professionals are less likely to report emotional exhaustion than are younger professionals (

Rosenberg and Pace 2006). As mental health professionals accumulate substantial work experience, they appear to be at lower risk for burnout (

Lim et al. 2010).

It is concerning that medical students show higher rates of psychological distress than do age-matched peers, especially since they are a subgroup of individuals with many strengths and lower rates of burnout and depression before medical school (

Baker and Sen 2016;

Brazeau et al. 2014;

Dyrbye et al. 2006). Students may also be less likely to seek care for medical or mental health problems because of fear of stigma or adverse academic or career consequences. For this reason, students need both easy access to confidential treatment and a culture that legitimizes self-care. Aspects of medical training that exacerbate symptoms of burnout and risk of psychiatric illness warrant change, even if major curricular and institutional modifications are needed to accomplish this (

Slavin et al. 2014).

The process of becoming a doctor is a process of identity formation (

Baker and Sen 2016). The training to become a medical professional or mental health care clinician brings serious risks. First, there are overt risk factors, such as long hours, heavy workload, sleep deprivation, financial strain, and mistreatment by authority figures. A hidden curriculum (

Hafferty and Franks 1994) values an unrealistic ideal of perfectionism and self-sacrifice. Trainees are often taught that their suffering is a normal part of the process and that admitting to struggling is an unwelcome sign of weakness in a highly competitive environment.

Table 1–2 summarizes the findings from a six-school study of depression and suicidal ideation in 2,193 physicians-in-training (

Goebert et al. 2009). The data reveal a concerning trend that females experienced more frequent depression symptoms, and ethnic minority students were at higher risk for suicidal ideation.

Evidence that students from underrepresented racial, ethnic, gender, and sexual minority groups are at substantial additional risk of depression (

Hunt et al. 2015;

Lapinski and Sexton 2014;

Przedworski et al. 2015) is even more troubling. In their recent study of students enrolled in 49 different medical schools,

Dyrbye and colleagues (2019) found that nonwhite students had significantly higher rates of depression. Although mentorship can be a critical ingredient for increasing both academic success and belonging, the persistent underrepresentation of faculty in academic medicine who identify as members of racial, ethnic, gender, and sexual minority groups means that students have minimal access to role models who may share critical aspects of their personal identities. Wellness programming should therefore include deliberate hiring of diverse staff and engagement of cultural consultants (

Seritan et al. 2015). Physical health disparities are already closely linked to class and race. If wellness programming is primarily designed by and for majority culture individuals, there is a good chance it will fail to adequately address the unique needs of underrepresented minorities (

Kirkland 2014).

Potential Problems With Wellness Programming

Wellness campaigns can be criticized for placing too much emphasis on a predetermined set of solutions and dismissing individual diversity. In fact, there are a wide range of viable solutions for enhancing the well-being of individual health care professionals. No particular set of solutions will be right for every professional. Although system supports are essential, engagement with wellness initiatives must be voluntary, selection of which activities to pursue must be individualized, and diverse perspectives on the desired outcomes must be respected. When making an effort to inspire groups of professionals to participate in activities to enhance wellness, great care must be taken to make sure campaigns do not become a new way to discriminate against people who have diverse life choices or development trajectories.

Aspects of both medical training and practice place psychiatrists and psychologists in particularly vulnerable positions. The nature of the work can feel isolating, and demanding schedules can limit the health care professional’s ability to be in connection with loved ones. At times when the young person’s developing identity is fragile, feedback systems can be designed to exploit this vulnerability to exact hard work and substantial personal sacrifice. Finally, the financial commitment required to complete training can add to the feeling that trainees are being exploited inappropriately. These factors contribute to the criticism that the field of medicine can feel like a cult at times. Although a growing emphasis on psychiatrist and psychologist well-being is an attempt to mitigate many of these problems, there is a risk that it can be one more form of unachievable perfectionism, placing too much of the blame on the individual health care professional already struggling to survive the pressures of a challenging job.

Kirkland (2014) makes a compelling case that institutions and leaders must be careful not to use wellness programming in a way that becomes discriminatory. In her article, Kirkland argues that wellness programming risks reproducing hierarchy and condoning discrimination based on personal health characteristics (

Kirkland 2014). Wellness programs may reward those who are already healthy and risk having little impact on those who have few resources or are coping with substantial health problems. The fallacy that health is primarily under individual control can also lead to assumptions that individuals who are not healthy, for whatever reason, deserve their lower status. For individuals with disabilities, there is even greater risk that narrowly defined wellness programming will further exclude them. Although civil rights laws protect employees from discrimination based on personal characteristics, and employers ordinarily cannot legally discriminate on the basis of employee health status, employers are allowed to offer health coverage at a reduced cost contingent on employee achievement of specified health goals. Careful consideration of the ways in which wellness programming can exacerbate existing disparities and legal protections for a diverse workforce is strongly needed.

Another concern is that doctors who promote themselves as wellness experts may actually alienate patients who might be intimidated to discuss their shortcomings with someone perceived to be thriving under similar circumstances. In primary care, for instance, an overweight patient may be reluctant to visit a physician who appears to be thin or whose online profile boasts about regular exercise. Emerging evidence suggests that when physicians express an inclusive philosophy related to self-care that acknowledges individual differences and a nonjudgmental attitude, patients may feel more comfortable (

Howe and Monin 2017). Although less is known about the extent to which this pattern is applicable to mental health care, it is reasonable to consider whether visible wellness activities of psychiatrists and psychologists may alienate patients who have psychiatric illness or significant relational problems. Certainly, inclusive messaging remains important in the mental health context.

Recognizing these pitfalls, the aim of this book is to take an authentic look at the important challenges related to professional wellness for psychiatrists’ and psychologists’ mental health care and to offer ideas for a self-compassionate approach to enhancing their well-being. Institutionally administered wellness programs may be harmful if they inadvertently isolate psychiatrists and psychologists who are already feeling vulnerable. A mindful approach dedicated to inclusivity and open listening is critical.

Recommended Resources

Brady KJS, Trockel MT, Khan CT, et al: What do we mean by physician wellness? A systematic review of its definition and measurement. Acad Psychiatry 42(1):94–108, 2018

Kirkland, A: Critical perspectives on wellness. J Health Polit Policy Law 39(5):971–988, 2014, 25037834

Lee J, Lim N, Yang E, Lee SM: Antecedents and consequences of three dimensions of burnout in psychotherapists: a meta-analysis. Prof Psychol Res Pr 42(3):252–258, 2011

MacKinnon M, Murray S: Reframing physician burnout as an organizational problem: a novel pragmatic approach to physician burnout. Acad Psychiatry 42(1):123–128, 2018

Roberts LW, Trockel MT (eds): The Art and Science of Physician Wellbeing: A Handbook for Physicians and Trainees. Cham, Switzerland, Springer, 2019

Thomas L, Ripp J, West C: Charter on physician wellbeing. JAMA 319(15):1541–1542, 2018