Understanding the clinical types of depression in late life is important for predicting clinical course and for choosing appropriate treatment. Clinical subtypes of depression in this older population include the following:

NEUROBIOLOGY

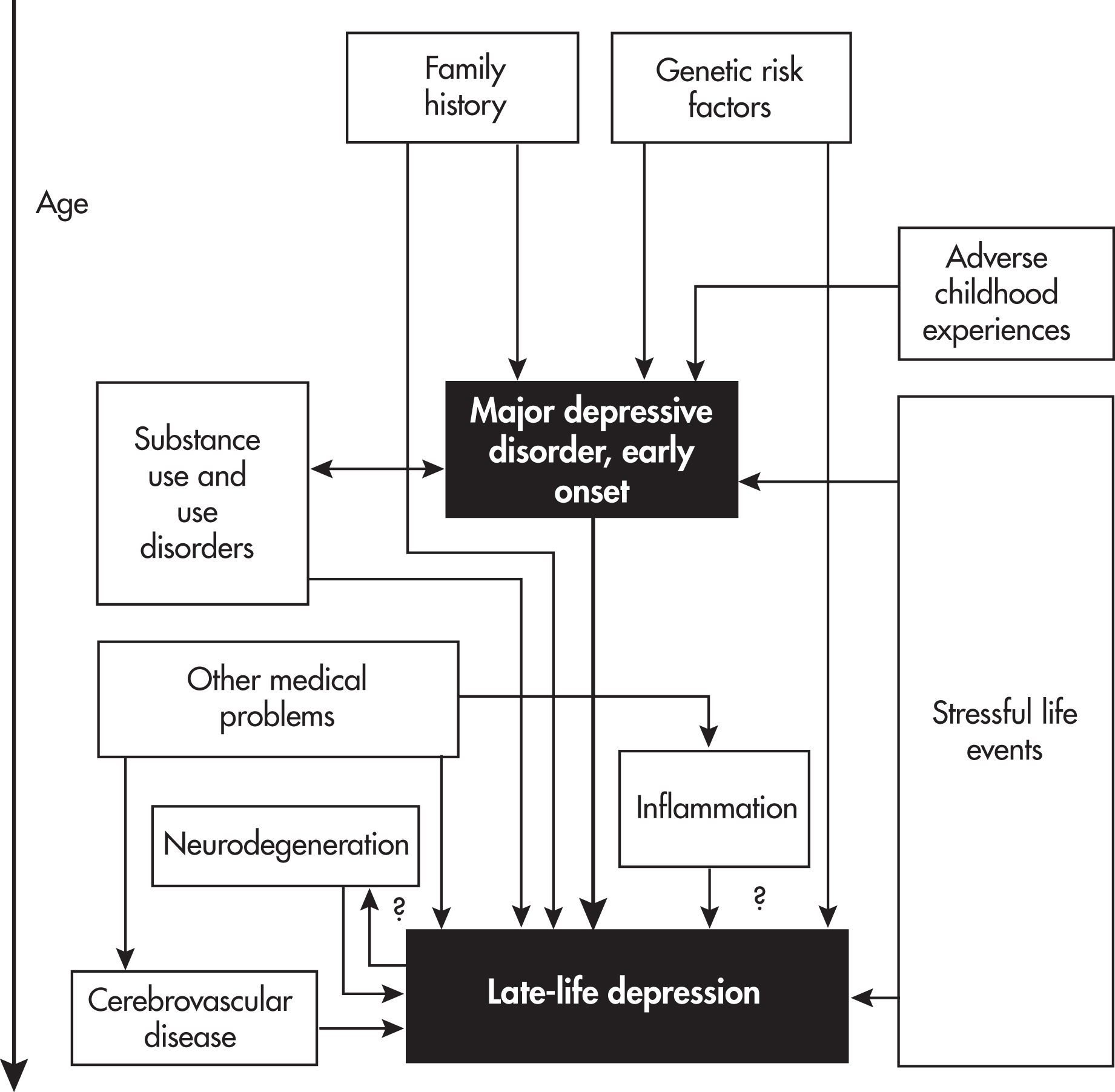

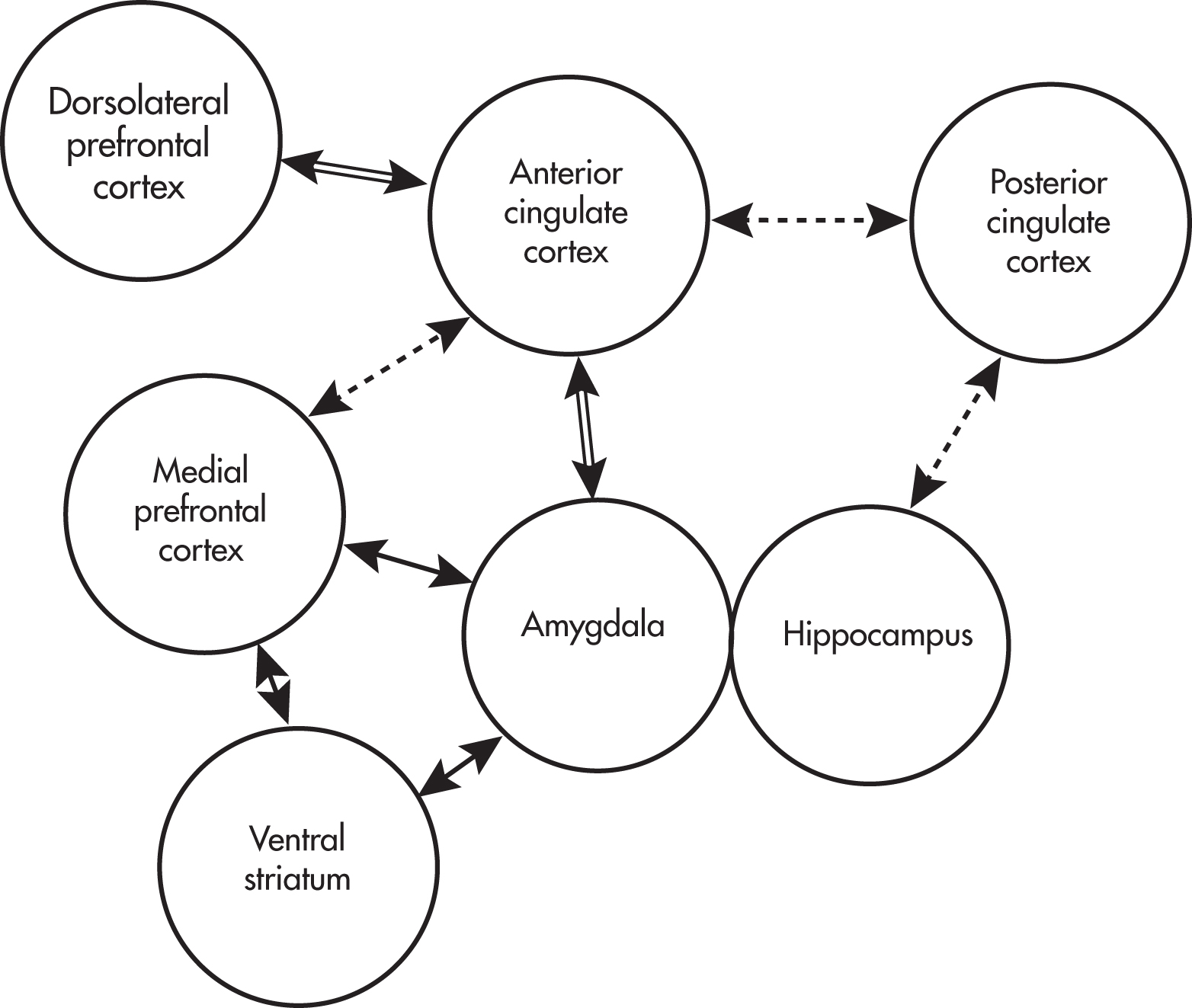

LLD may arise from disruption of the neural circuitry involved in emotion regulation, especially frontal-executive and corticolimbic circuits (

Rashidi-Ranjbar et al. 2020). Various networks are thought to be involved in emotion regulation, including the default mode network, an executive control network, and a network involved in reward and reinforcement (

Kupfer et al. 2012). These networks include parts of the prefrontal cortex (e.g., the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), hippocampus, amygdala, posterior cingulate cortex, and white matter tracts connecting these and other structures (see

Figure 1–3). Anhedonia may arise from abnormalities in the reward network, executive dysfunction may arise from abnormalities in the executive control network, and rumination may arise from abnormalities in the default mode network.

Cerebrovascular disease, especially ischemic changes in white matter, is a primary cause of this disruption of neural circuitry (

Alexopoulos 2019). Location of disease in white matter and extent of white matter disease have been associated with LLD, especially late-onset depression. Persons with LLD have been found to have decreased resting cerebral blood flow in the frontal lobes. Vascular risk factors in midlife, including hypertension and diabetes, are also risk factors for LLD. This strong link between cerebrovascular disease and depression has led to the construct of

vascular depression, discussed in greater detail in the subsection

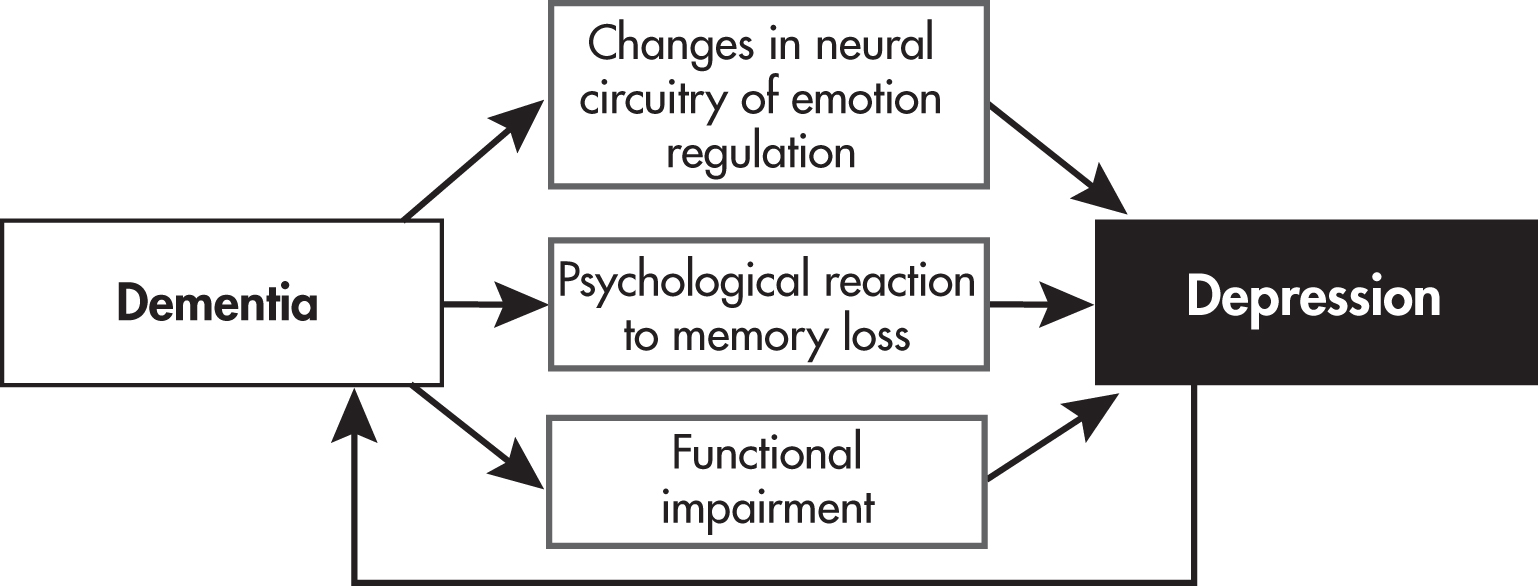

“Vascular Depression.”The high rate of depression in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease suggests that neurodegeneration affects not only cognition but also emotional functioning. Several Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers (e.g., burden of amyloid plaques in the frontal cortex and hippocampus) have been associated with depression in older adults with and without dementia (

Alexopoulos 2019). Depression, especially late-onset depression, may be a risk factor for dementia and for progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia, suggesting a two-way relationship between dementia and depression; we discuss this in greater detail below.

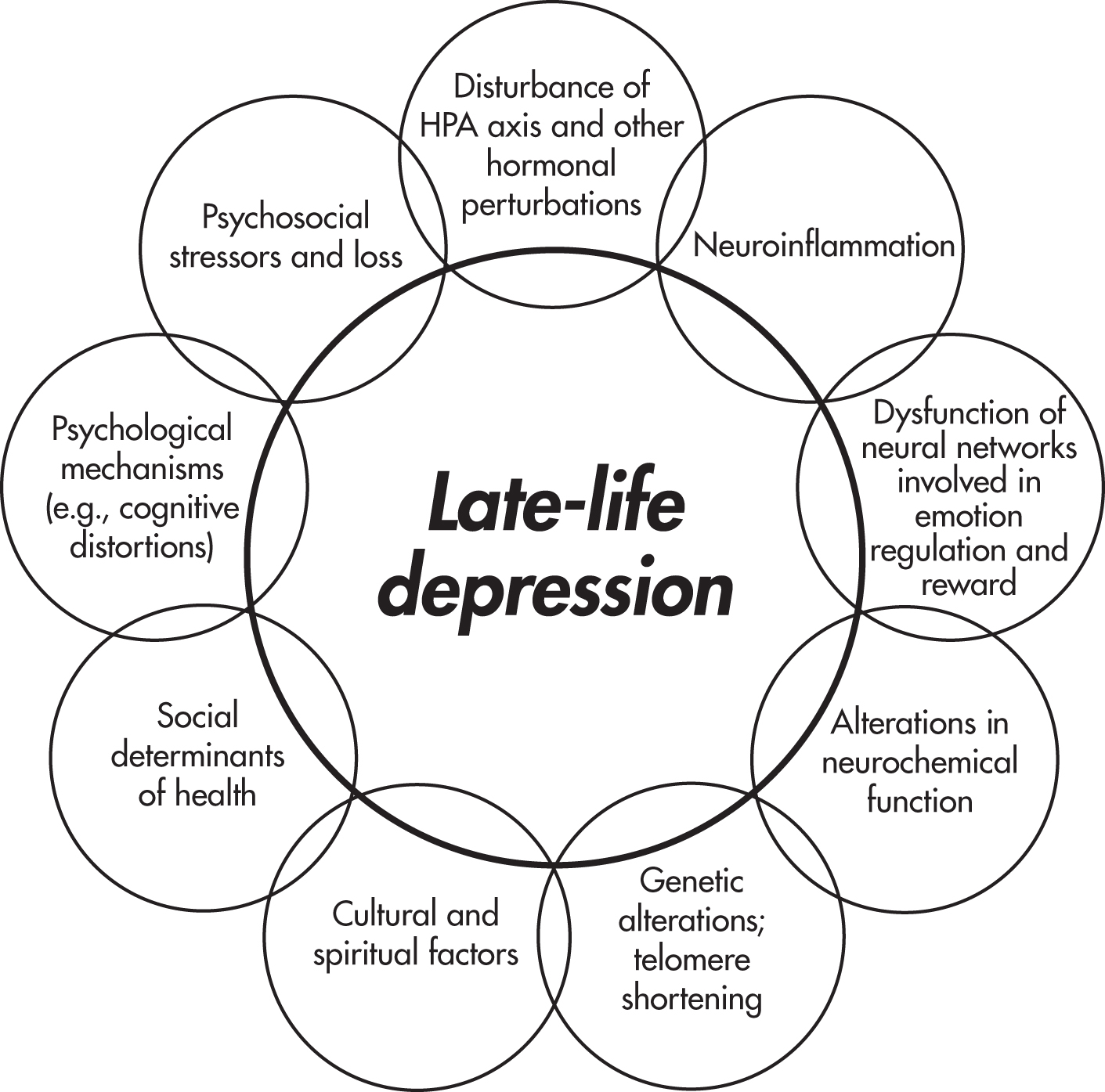

Peripheral inflammatory markers have been associated with LLD, suggesting a pathway from aging to peripheral inflammation to central nervous system inflammation to depression (

Martínez-Cengotitabengoa et al. 2016;

Miller et al. 2013). For example, a large longitudinal study measured an inflammatory marker, C-reactive protein (CRP), in midlife, 7 years later, and another 14 years later, at which time depressive symptoms were also assessed; elevated CRP at two or more time points was associated with LLD (

Sonsin-Diaz et al. 2020). This link raises the possibility of anti-inflammatory approaches to preventing or treating depression.

LLD has low to moderate heritability (14%–55%), suggesting a modest role for genetic factors (

Tsang et al. 2017). Elders with early-onset depression are more likely to have a family history of depression than do those with late-onset depression (

Gallagher et al. 2010). However, most genetic studies of LLD have not distinguished between early-onset and late-onset depression, making it hard to figure out how much of the genetic contribution to LLD is mediated by depression earlier in life. Carriers of the e4 allele of the

APOE gene, an allele associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, may also be at slightly increased risk of LLD (

Tsang et al. 2017). Cognitively intact elders with depression who are

APOE ε4 carriers may be at higher risk for cognitive decline (

Morin et al. 2019). Note that most subjects in the

APOE studies have been non-Hispanic white people, limiting generalizability. Polymorphisms involving genes encoding neurotrophins such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) have also been associated with LLD (

Miao et al. 2019;

Tsang et al. 2017). In younger populations, carrying the S allele of

SLCA64 (which results in less transcription of serotonin transporter) moderates the relationship between stressful life events and depression; the same polymorphism confers a slightly increased risk of LLD (

Tsang et al. 2017). Depression has been associated with telomere shortening, a marker of cellular aging (

Ridout et al. 2016).

Dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a hallmark of depression in younger adults. Older adults with depression can have either hypocortisolemia or hypercortisolemia, with the latter possibly associated with smaller hippocampal volumes (

Bremmer et al. 2007;

Geerlings and Gerritsen 2017). Women who undergo menopause later (i.e., have greater exposure to estrogen) have a lower risk of subsequently developing depression, even among women with a history of premenopausal depression (

Georgakis et al. 2016). Estrogen has antidepressant and neuroprotective properties, although perhaps only during the perimenopausal period because estrogen has not been found to be effective for depression in women after menopause (

Georgakis et al. 2016). The literature on the relationship between low testosterone and depression in older men is mixed (

Walther et al. 2019).

Aside from neurodegenerative disorders, stroke, hypertension, and diabetes, other medical conditions have been associated with LLD. These conditions include coronary artery disease (including myocardial infarction), chronic pain, arthritis, hearing loss, vision loss, sleep apnea, cancer, thyroid disease, hyperhomocysteinemia, and vitamin B

12 deficiency (

Aziz and Steffens 2013;

Kerner and Roose 2016). This list becomes especially pertinent when we seek to identify reversible causes of depression in our patients, which we cover in

Chapter 3. A number of medications have been associated with LLD, including steroids, β-blockers, benzodiazepines, opioids, and antiparkinsonian agents (

Aziz and Steffens 2013). (Note that some of these medications can also cause euphoria or mania, in particular steroids and antiparkinsonian agents.) Excessive use of alcohol, benzodiazepine use disorder, and opioid use disorder have been associated with LLD (

Wu and Blazer 2014).

PSYCHOSOCIAL, PSYCHOLOGICAL, AND PERSONALITY FACTORS

For a comprehensive review, readers are referred to incisive articles by

Areán and Reynolds (2005) and

Laird et al. (2019).

Table 1–1 summarizes the findings from these reviews. In general, older adults experience a number of stressful life events, most notably the deaths of a partner and other loved ones, which in turn may result in loss of social supports and loneliness. Some stressors may be somewhat unique to aging, such as the loss of driving privileges due to physical or cognitive decline, which has been associated with a doubling of the risk of depression (

Chihuri et al. 2016). The stressors do not have to be recent: older adults who had experienced one or more adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), especially those with low perceived social support, are at higher risk of LLD (

Cheong et al. 2017). Older women, ethnic and racial minority elders, and sexual minority elders may continue to face sexism, racism, homophobia, and transphobia as they age. Increased living expenses while on a fixed income, neighborhood crime, food insecurity, and problems with access to and affordability of medical care may contribute to depression. Like younger adults, older adults may have a number of maladaptive personality traits and coping strategies that precipitate or perpetuate depression. Conversely, resilience may be protective (

Laird et al. 2019).

In my practice, I have found older adults’ despair about a perceived loss of meaning and purpose to be an especially powerful and difficult-to-address component of LLD. For a more in-depth review of the role of meaning and purpose in psychological well-being, cognition, and survival, I recommend reading the section

“Capacity Assessment” in

Chapter 6.

It is helpful to understand how the psychology of LLD informs evidence-based psychotherapy (

Kiosses et al. 2011). For example, the recognition that grief, loneliness, role transitions (e.g., retirement, becoming a caregiver), interpersonal skills deficits, and interpersonal conflicts can contribute to depression forms the basis of interpersonal psychotherapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy seeks to address negative dysfunctional thoughts, distorted perceptions and beliefs, and the withdrawal or inactivity that accompany depression. Because cognitive impairment and executive dysfunction can accompany depression in older adults, problem-solving therapy focuses on “teaching patients skills for improving their ability to deal with specific everyday problems and life crises . . . . Patients identify problems, brainstorm different ways to solve their problems, create action plans, and evaluate their effectiveness in implementing the best possible solution” (

Kiosses et al. 2011).

CULTURAL AND SPIRITUAL FACTORS

We devote

Chapter 6 to a comprehensive review of cultural and spiritual factors in the care of older adults with depression and anxiety. Here we discuss the roles of culture and spirituality in contributing to LLD. Please note that I use the ethnic/racial terminology used in the original papers.

Culture refers to “a set of shared symbols, beliefs and customs that shapes individual and/or group behavior” (

Dilworth-Anderson and Gibson 2002). Culture influences how people define a mental health problem, how they perceive the cause of the problem, how they cope with the problem, and whether and how they seek help for the problem (

Aggarwal 2010). A tool such as the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview, discussed in

Chapter 6, can help the clinician better understand the role of culture in an elder with depression.

Culture may affect how depression manifests in older adults. For example, Black African, Caribbean, and South Asian elders in the United Kingdom are less likely to report guilt, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation than are White British elders. This could reflect a different presentation of LLD (fewer affective, more somatic symptoms) or lower acceptability of reporting such symptoms (

Mansour et al. 2020).

The experience of being an ethnic minority or immigrant may contribute to developing LLD. Being an older adult who immigrated may be protective against depression (e.g., because of the

healthy migrant effect, the hypothesis that the immigration process selects for more psychologically resilient people) or a risk factor (e.g., because of loss of power or status within the new culture) (

Mansour et al. 2020;

Sadavoy et al. 2004). Among immigrants to Western nations, intergenerational conflict over traditional versus Western-based values may serve as a stressor contributing to depression (

Sadavoy et al. 2004). For example, Asian elders may feel disappointment in their adult children with respect to

filial piety, “the spirit and principle of being considerate and respectful toward one’s parents and older family members”: Asian older adults’ satisfaction with their children’s filial piety is correlated with lower level of depression (

Wu et al. 2018, p.370). Latinx elders may have expectations regarding

familismo, the “intergenerational obligation, respect, and the duty to care for aging parents” (

Wu et al. 2018, p.376).

Language barriers and challenges navigating social and medical systems may contribute to social isolation, in turn a risk factor for LLD (

Sadavoy et al. 2004). Elders of various cultural backgrounds may view depression as a personal or familial matter not requiring a medical intervention (

Flores-Flores et al. 2020;

Ward et al. 2014). Ethnic minority elders may face challenges with respect to accessing linguistically and culturally appropriate services and are less likely to receive appropriate treatment, including antidepressants and psychotherapy (

Mansour et al. 2020;

Sadavoy et al. 2004). African American and other ethnic minority elders in the United States experience psychological distress as a result of racism, discrimination, prejudice, and poverty (

Conner et al. 2010). African American elders are less likely to seek treatment for depression than are white elders because of mistrust of the health care system, stigma about mental illness, and alternative methods of coping (e.g., religious practices) (

Conner et al. 2010). Depressed Black elders are 61% less likely to receive any depression treatment than are non-Hispanic white elders (

Vyas et al. 2020).

In general, religion and spirituality have been associated with reduced risk of depression. There is some evidence that religious practices (such as attendance at religious services and prayer) are more protective against LLD than are religious beliefs alone (

Laird et al. 2019). Spirituality may be especially important with respect to addressing LLD. For example, older African Americans may be more likely to turn to religious counsel (e.g., clergy) and may wish to incorporate religious practices into treatment of depression (

Pickett et al. 2013).

We cover social determinants of health in

Chapter 6.