Suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) are major public health problems. Suicide is the third leading cause of death among youth 10 to 24 years of age, and national surveillance data indicate an annual suicide attempt (SA) rate of approximately 6.3% among high school students.

1 NSSI, defined as deliberate self-harm without suicidal intent (e.g., cutting, burning), is at least as common as suicidal behavior, although rates vary across studies, underscoring the impact of sampling and methodological factors.

2,3 The significance of NSSI as a treatment target in clinical samples is underscored by surveys of mental health providers indicating that NSSI is a more frequent problem than SAs among their patients.

4Despite increasing recognition of NSSI, its prognostic significance with respect to depression response and suicidal behavior is not well understood.

5–7 This article reports secondary analyses examining NSSI and SAs cross-sectionally and longitudinally in the Treatment of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI)–Resistant Depression in Adolescents (TORDIA) study, a large multi-site study of chronically depressed adolescents. Given the links between depression and suicidal behavior, as well as emerging data indicating that depression is associated with NSSI, this sample of youths with severe and treatment-resistant depression offers a unique opportunity to examine patterns of SAs and NSSI in a high-need clinical sample.

Compared with our knowledge of adolescent suicidal behavior, less is known about correlates and predictors of NSSI in adolescents, in part because efforts to clearly distinguish between self-injurious behavior with and without suicidal intent have been relatively recent. Extant research indicates that youths with a history of NSSI have elevated rates of depressed/anxious symptoms, conduct problems, substance use, symptoms of borderline personality disorder, dissociative symptoms, stress, and histories of abuse/violence.

2,8,9 NSSI also appears to be associated with elevated rates of SAs and to predict future suicide and SAs in adults.

2,10–13 The question of whether NSSI predicts future suicide/SAs in adolescents requires evaluation.

In a previous report, focusing on acute treatment outcomes at 12 weeks in the TORDIA study sample, we found relatively high incidence rates of suicidal adverse events (new-onset or increased suicidal ideation or an attempt, present in 11.3% of youths). However, the rate of new-onset SAs was only 5%, and NSSI was present in 9% of the sample, during these 12 weeks.

14 Although predictors of suicidal events included drug and alcohol use, family conflict, and higher levels of intake suicidal ideation, the strongest predictor of incident NSSI was a previous history of NSSI; it was found that NSSI history was not a significant predictor of suicidal events during the 12-week acute treatment period.

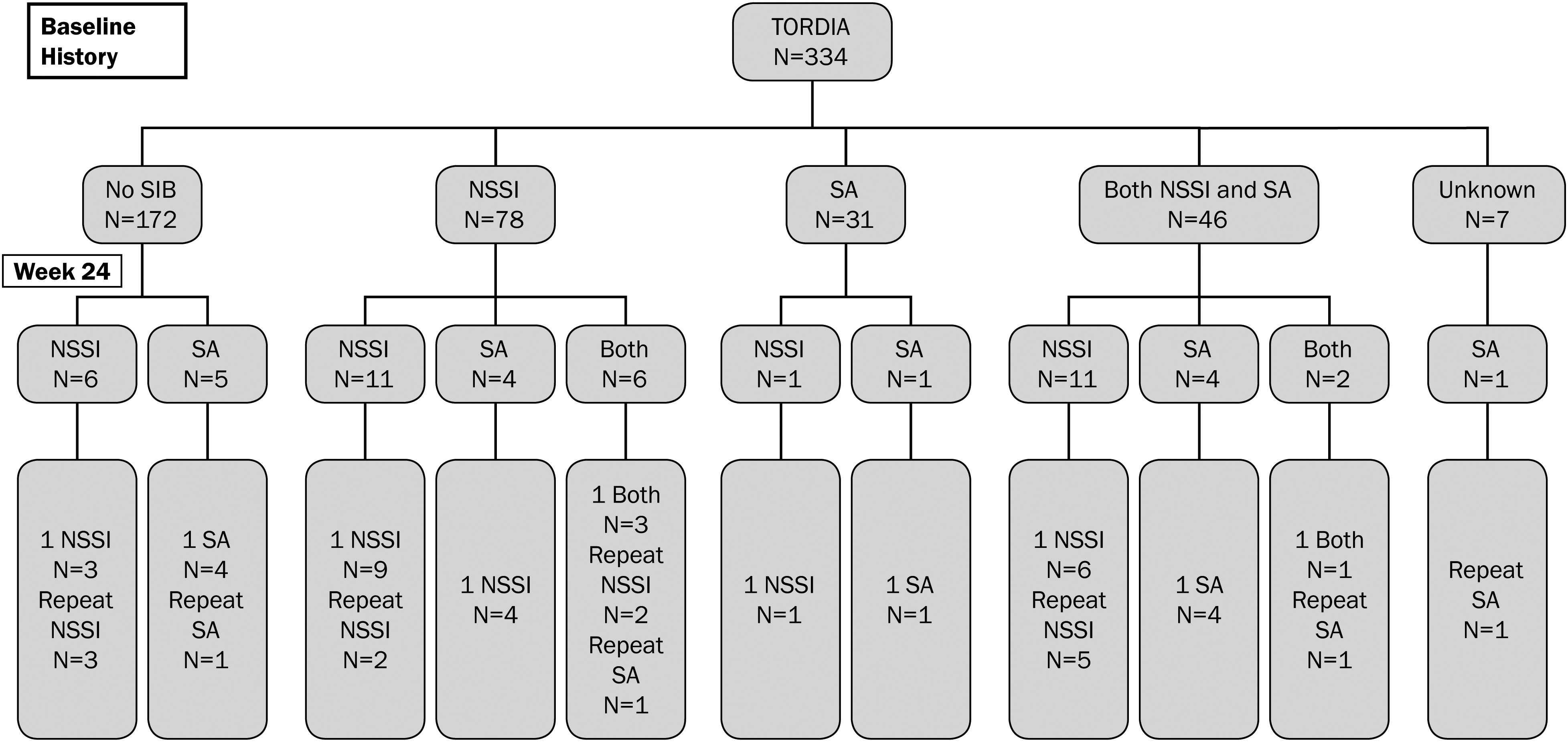

14 Other predictors of NSSI through week 12 were self-reported suicidal ideation, history of abuse, and history of suicide attempts. We now extend these results to examine the progression of self-injurious behavior (SA and NSSI) over an additional 12 weeks of continuation treatment for a total of 24 weeks or 6 months. Specific aims of this article are as follows: 1) to describe NSSI and SA outcomes through the 24-week treatment period; 2) to compare rates of incident NSSI and SAs among youths with baseline histories of NSSI, SAs, and both NSSI and SAs; 3) to explore other predictors of SAs and NSSI over the 24-week treatment/follow-up period; and 4) to present new analyses of correlates of NSSI and SA histories at the initial/baseline evaluation. Based on prior literature indicating that suicide attempts are predicted by prior suicide attempts

15 and emerging literature indicating that prior NSSI predicts future NSSI,

14 we predicted that SAs and NSSI during the 24-week treatment period would be predicted by baseline histories of self-injurious behavior of the same type. We hypothesized that the strongest predictors of SAs would be depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation, whereas NSSI was predicted to be more strongly associated with abuse histories and substance use, problems often associated with personality disorders.

12,13 Given prior research indicating that NSSI and suicidal behavior are associated forms of self-injurious behavior, we predicted a significant association between baseline histories of NSSI and SAs.

12,14Method

Detailed descriptions of participants, assessments, treatments and outcomes are available elsewhere.

14,16,17 Therefore, we focus here on participant characteristics, measures, and procedures relevant to the outcomes of SAs and NSSI. The study was reviewed by each site’s local institutional review board. All subjects gave informed assent/consent (as appropriate), and parents gave informed consent.

Participants

Participants were adolescents 12 to 18 years of age, with moderate to severe

DSM-IV18 major depressive disorder (MDD) and clinically significant depression (Child Depression Rating Scale—Revised (CDRS-R)

19 total score ≥40 and a Clinical Global Impression— Severity (CGI-S) Subscale ≥4 (moderate or greater severity)

20 despite being in active treatment with an SSRI for ≥8 weeks (

Table 1). The sample was 69.7% female, with a mean age of 15.9 years. Exclusion criteria were bipolar spectrum disorder, psychosis, pervasive developmental disorder or autism, eating disorders, substance abuse or dependence, or hypertension.

Randomization

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: change to another SSRI, change to venlafaxine, change to another SSRI plus CBT, or change to venlafaxine plus CBT. Subjects were assigned to treatment using a variation of Efron’s biased coin toss,

21 balancing both across and within sites with respect to incoming treatment medication, comorbid anxiety, chronic depression (duration ≥24 months), and BDI item 9 (suicidal ideation) ≥2.

Interventions

Pharmacotherapy. Medication sessions occurred weekly during weeks 1 to 4, then biweekly until week 12. Adjunctive medications for sleep and for anxiety, as well as stimulants (for youths on stimulant treatment at study entry), were allowed. Subjects with a clinically acceptable response (CGI-I ≤2 and ≥50% decrease on CDRS) received 12 additional weeks of continuation treatment. Nonresponders were offered open treatment.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. In TORDIA, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) was flexible and encouraged selection of modules/skills based on patients’ clinical needs. Modules/skills emphasized cognitive restructuring, behavior activation, emotion regulation, social skills, problem solving, and parent–child sessions to improve support, decrease criticism, and improve family communication and problem solving.

16 The protocol included ≤12 CBT sessions during weeks 1 to 12, biweekly visits for the next four sessions, then monthly until week 24.

Assessments

Baseline Diagnostic/Clinical Assessment. Diagnostic symptoms, including SAs and NSSI, were assessed using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children—Present and Lifetime Versions (K-SADS-PL)

22 administered by an independent evaluator (IE) with a graduate degree in a mental health field. An SA was defined as “self-harm with actual or inferred intent to die.” NSSI was defined as “self-injurious behavior resulting in physical damage with no explicit or implicit intent to die.” These variables were recorded by the IE at the end of the second (week 0) baseline evaluation and represent best estimate ratings based on youth and parent responses to the KSADS SA and NSSI questions and all other available information from the initial (week −2) and second (week 0) assessments.

14,16,23 Interviewers rated overall severity, functional impairment, and depression severity using the Clinical Global Improvement Severity Subscale (CGI-S),

20 Child Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS),

24 and the Child Depression Rating Scale—Revised (CDRS-R),

19 respectively. Self-rated depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),

25 Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS),

26 and Suicide Ideation Questionnaire—Jr. (SIQ-Jr.),

27 respectively. History of physical or sexual abuse was obtained from the trauma section of the K-SAD-PL. Adolescents rated parent–child conflict using the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire—Adolescent (CBQ).

28 Alcohol and drug use were rated using the self-report Drug Use Screening Inventory (DUSI).

29 Primary Outcomes. The two primary outcomes were as follows: 1) a SA, defined as a deliberate selfinjurious behavior with some non-zero intent to die; and 2) NSSI, defined as deliberate self-harm without suicidal intent. We refer to either of these outcomes as “self-injurious behavior” (SIB). These SIB outcomes were assessed during the 24-week trial using adverse events records, discussed on weekly conference calls with the site investigators, and classified by consensus.

14 Clinical raters were blinded to medication but not to CBT status. As described elsewhere,

14 for the first 181 participants, suicidal events were based on spontaneous report. However, following concerns/ warnings regarding increased risk of suicidality with antidepressant medications,

30 the last 153 subjects were monitored weekly by clinicians for suicidal ideation and SIB using the Clinician Weekly Rating Scale and Brief Suicide Severity Rating Scale (B-SSRS).

14, 31 Interrater reliability was assessed on 49 cases and was found to be excellent for SAs and NSSI (100% agreement).

Follow-up. Of 334 participants randomized, follow-up data were available on 287 (85.9%) at 12 weeks, and 279 (82.3%) by 24 weeks, the end of continuation treatment.

Statistical analyses

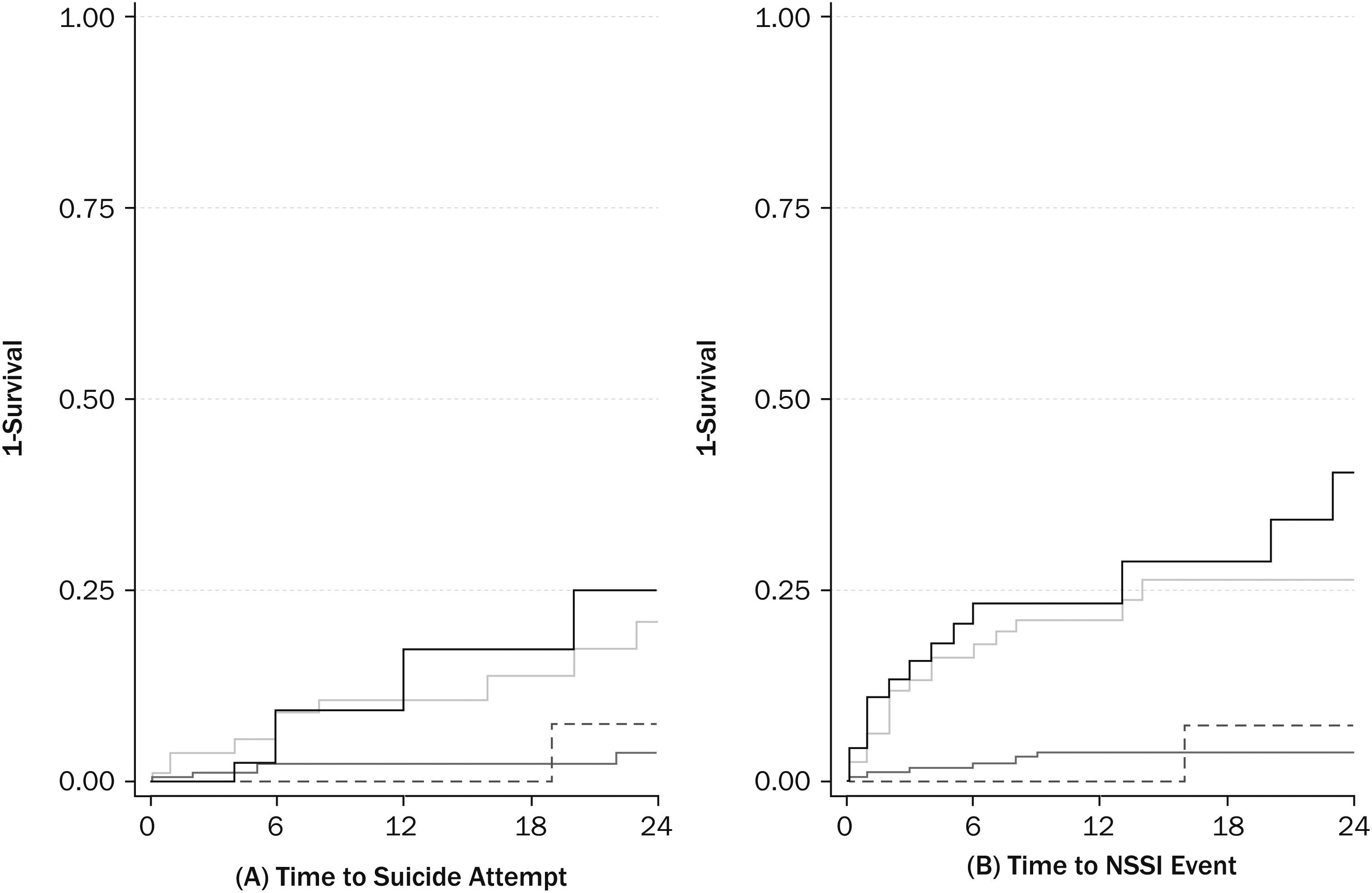

Parallel analyses were conducted for SAs and NSSI. We report frequency of SAs and/or NSSI at baseline and examined associations among these variables and baseline clinical, demographic, and background variables using standard univariate statistics. Predictors of time to event (SA, NSSI) were examined using log-rank tests for categorical variables and Cox regression for continuous variables. The most parsimonious set of predictors were identified using a backward stepwise Cox proportional hazards method. Each variable that was selected as a predictor of SA or NSSI events was then added to a logistic regression that also included terms for medication and CBT treatment effects and all two way interactions. The rate of SA detection was not significantly different before and after systematic monitoring [χ2 (1) = 2.26, p = .13]. However, NSSI was rarely detected without systematic monitoring [31 of 37 youths (83.8%) with NSSI identified under systematic monitoring, χ2 (1) = 24.17, p < .001]. Restricting analyses to participants with systematic monitoring led to the same conclusions; therefore, we report only primary analyses using the full sample.

Discussion

The present results underscore both the prevalence and significance of NSSI among adolescents with chronic treatment-resistant depression. Consistent with results indicating relatively high rates of NSSI in the general adolescent population,

2,8 NSSI histories were relatively common in the TORDIA sample (38%) and more common than SA histories (23%). In addition, NSSI and suicide attempts tended to co-occur, with 14% of the sample presenting with baseline histories of both NSSI and SAs, and these youths frequently presenting with double depression (major depression superimposed on dysthymic disorder). Youths with histories of both NSSI and SAs also reported the highest levels of suicidal ideation, hopelessness, depressive symptoms, family conflict, and were most likely to have histories of physical or sexual abuse. Although a history of SAs or NSSI was also associated with increased problems, on average these youths fell between the no-SIB group and the combined NSSI plus SA group on study variables.

NSSI was also more common than SAs over the course of the treatment trial, which extended from 12 weeks of acute treatment for another 12 weeks of continuation treatment. Rates of NSSI through the 24-week/6-month treatment period were high, and were particularly high among youths with baseline histories of combined NSSI and SAs and NSSI alone. SAs were also disturbingly common during the 24-week treatment period, underscoring the high-risk status of these youths, particularly since a previous SA and major depression are among the strongest predictors of completed suicide in this age group.

15 History of NSSI at baseline was a significant predictor of SAs through week 24, and a stronger predictor than baseline SA history, again underscoring the need to evaluate, monitor, and effectively treat NSSI in youths with treatment-resistant depression.

Future research is needed to clarify the processes contributing to the higher rate of SAs during the TORDIA trial among youths presenting with NSSI histories at baseline. Our finding that baseline suicide attempt history was not a significant predictor of SAs through week 24 was surprising, given the conventional view that SAs are more pernicious than NSSI.

32 However, our results are consistent with those of a recent report from the Adolescent Depression Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT), which similarly reported that NSSI history at baseline (but not SA) was a significant predictor of SAs over 28 weeks.

33 There are several possible explanations for these findings. NSSI and SAs may be on the same spectrum of self-harm behavior, and may share similar correlates and risk and protective factors.

32 For instance, the Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) model posits that youths with NSSI could have emotion regulation deficits that are risk factors for both future NSSI and SAs.

11 It could also be that expressing self-harm impulses in an SA may have a short-term effect of reducing SA risk because of resulting interventions (e.g., SA means restriction or increased treatment intensity). Alternatively, NSSI may not yield changes in treatment plans, and when NSSI also fails to produce sufficient relief (intrapersonal and/or interpersonal effects), vulnerable youths may turn to SAs.

32 Another possibility is that engaging in NSSI desensitizes youths to selfharming behaviors, thus lowering the barriers to SAs and NSSI.

34 Although the temporal relationship of NSSI and SA in this study are consistent with that view, the sequence of self-harm events is equally consistent with the other explanations described above.

It is important to consider the present findings in relation to overall results of the TORDIA trial. Primary outcome analyses revealed that youths receiving combined CBT plus a medication switch were more likely to have a positive treatment response than youths receiving a medication switch alone (55% versus 40.5%).

16 Furthermore, baseline NSSI-history predicted poor response and limited benefits from the TORDIA CBT.

23 Although approximately 60% of youths eventually attained remission, remission rates were less than 40% at 24 weeks, and nearly 20% of those showing a good response by 12-weeks experienced a relapse upon follow-up.

17,35 Slow recovery from depression has been associated with a higher risk for suicidal events both in TORDIA and in the Treatment of Adolescent Depression Study (TADS).

36 Also, in the ADAPT study, NSSI occurrence was greater in those individuals with a slower recovery from depression.

33 Therefore, interventions that will accelerate treatment response in adolescent depression may reduce the incidence of suicidal events and NSSI. Furthermore, depression treatment may need supplementation with interventions targeting specific risk factors for SIB, such as problems with emotion regulation and distress tolerance.

Study limitations merit consideration. Although the TORDIA sample included a diverse and under-studied group of adolescents with relatively chronic depressions, results may not generalize to less chronically depressed, untreated, or nonreferred samples where NSSI is often found without chronic, or even acute depression. Statistical power limited our ability to detect differential effects within subgroups and potential effect modifiers. A more detailed assessment of NSSI that evaluated the degree to which NSSI was repetitive and the functions and motivations for NSSI would have provided additional information. We did not assess personality disorders, and SIB history may have been associated with risk for borderline or other personality disorders. The TORDIA study was a treatment trial, with close clinical monitoring. Although the best efforts of the TORDIA team did not eliminate SAs and NSSI, the observed rates may underestimate incidence rates under routine practice conditions. Although the sample was followed through week 72, weekly adverse event monitoring stopped at 24 weeks when the continuation treatment protocol concluded, limiting our ability to examine NSSI and SA outcomes beyond week 24. Spontaneous reports of SIB were supplemented by systematic monitoring mid-way through the study due to concerns regarding increased suicidality with antidepressant medications. NSSI was rarely detected without systematic monitoring; however, sensitivity analyses restricting the sample to the subgroup of youths with systematic monitoring yielded similar results.

In conclusion, the present results underscore the clinical significance of NSSI and SAs among youths with treatment-resistant depression. NSSI was common in the histories of these youths, and predicted both SAs and NSSI over the course of the first 6 months of the trial as well as a poor response to the TORDIA treatments, particularly CBT.

23 These data indicate that better assessment and intervention strategies for NSSI may be helpful in the management of treatment-resistant depression, as well as the prevention of suicidal behavior.