INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, a specialized cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for hoarding disorder (HD) has been developed, based on scientifically grounded models of HD, which includes motivational interviewing (efforts to increase motivation to change and adherence to treatment), graded exposure to nonacquiring (gradually building ability to resist the urge to buy or otherwise acquire items), training in sorting and discarding (practicing effective decision making using challenging questions), cognitive restructuring (identifying and correcting maladaptive patterns of thinking), and organizational training (practicing appropriate handling and placement of items to be saved in order to reduce clutter in the home). For more details about the specific CBT procedures, the reader is directed to published treatment manuals.

[1–3] Hoarding-specific CBT has now been tested in both individual

[4,5] and group

[6–8] formats; concurrently, specialized assessment instruments have made it possible to assess not only the presence of HD, but also outcomes for the specific symptoms of difficulty discarding, acquiring, and clutter, as well as associated functional impairment.

[9] Outcomes of clinical trials of CBT for HD have generally yielded positive results, although it has been noted that many, if not most, patients continue to experience some degree of hoarding symptoms and associated impairment at posttreatment.

[10] To date, no studies have examined treatment outcome across studies in HD samples, as has been done for hoarding symptoms within obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) samples.

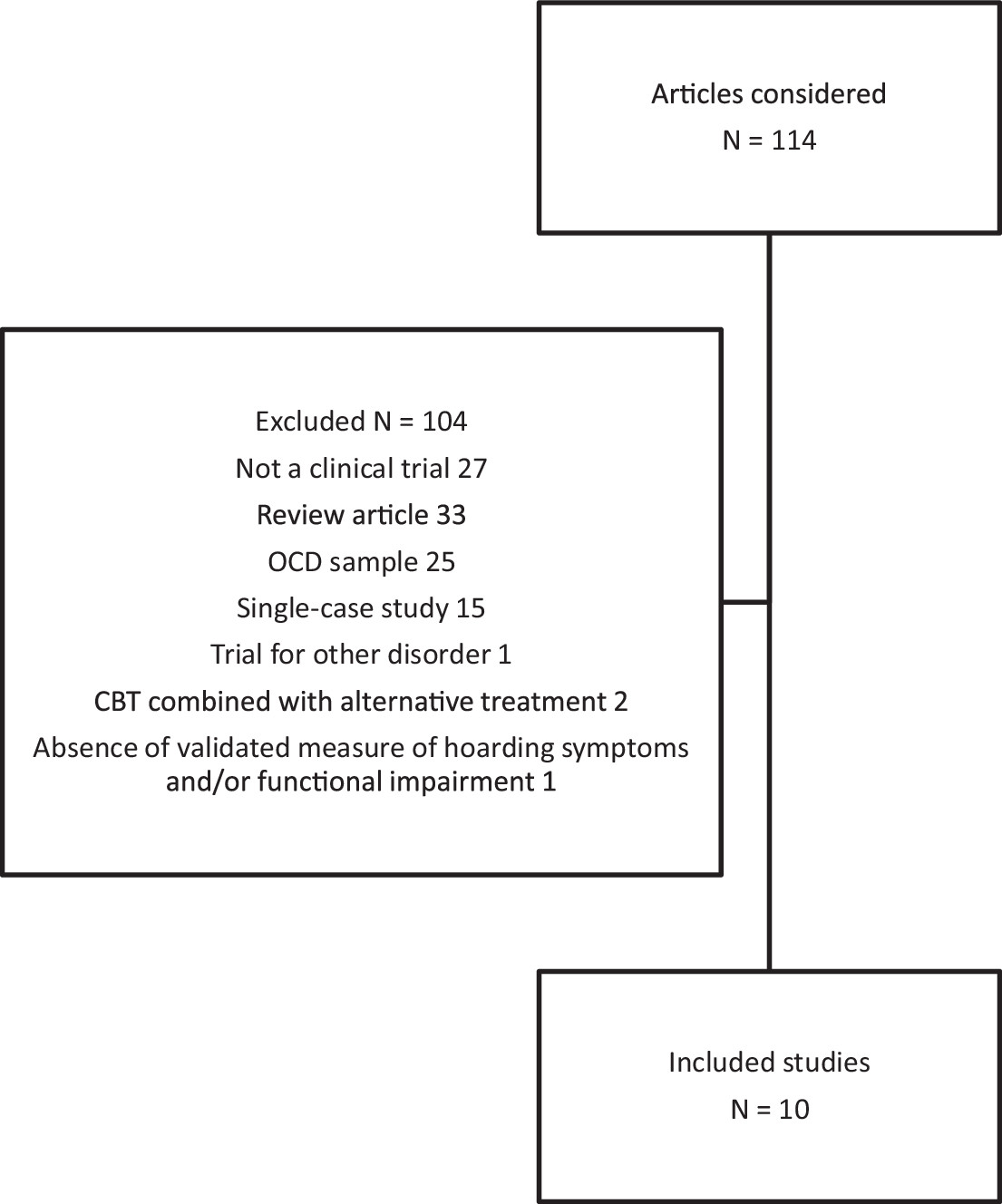

[11] The primary aim of the present meta-analysis is to examine the within-group effect size of CBT for HD, with attention to overall HD severity as well as to the individual symptoms of clutter, difficulty discarding, acquiring, and associated impairment.

The fact that the treatment of HD is still very much a “work in progress” makes this an ideal time to examine factors that predict CBT outcome. Understanding predictors of treatment success would likely help efforts to refine treatment protocols. One trial of CBT in older adults yielded poor outcomes,

[12] although another seemed more promising.

[13] Despite a roughly equal prevalence of HD in men and women,

[14] most trials have included relatively few men, making it difficult to understand the relationship between gender and HD treatment outcomes. Depression, the most common comorbid condition in HD,

[15] may also be a complicating factor in CBT; some studies have suggested that severe depression is associated with attenuated treatment outcome in OCD.

[16,17] Furthermore, medication status may also be predictive; in OCD, patients receiving antidepressant medications along with CBT show somewhat better outcomes across studies than do patients receiving CBT without medications.

[18] Understanding the relationship between the number of sessions (both in the home and in the office) and outcome would help identify a dose-response relationship of CBT and examine the necessity of home visits; one trial suggested only modest benefits from increasing the number of sessions in the home.

[19] Investigating the impact of treatment parameters, such as individual versus group sessions and the presence of a professional clinician, may help improve the efficiency of treatment, which can be somewhat labor-intensive in its original form,

[4,5] but has shown promise in group settings

[6–8] and with trained lay counselors.

[20,21] Thus, the second aim is to examine whether demographic and treatment-related variables are associated with differential CBT response.

The third and final aim is to examine, for each outcome domain, the proportion of patients achieving reliable and clinically significant change. As has been noted qualitatively,

[22] many patients remain significantly symptomatic after the completion of CBT. By examining the proportion of patients meeting criteria for reliable change (change in the outcome measure is significantly greater than that expected by chance, given the test-retest reliability of the measure) and clinically significant change (posttreatment scores that better match the distribution of scores in the general population than in a hoarding population), we will be able to make stronger conclusions about the efficacy of CBT for HD than would be possible with estimates of statistical significance alone.

[23,24]DISCUSSION

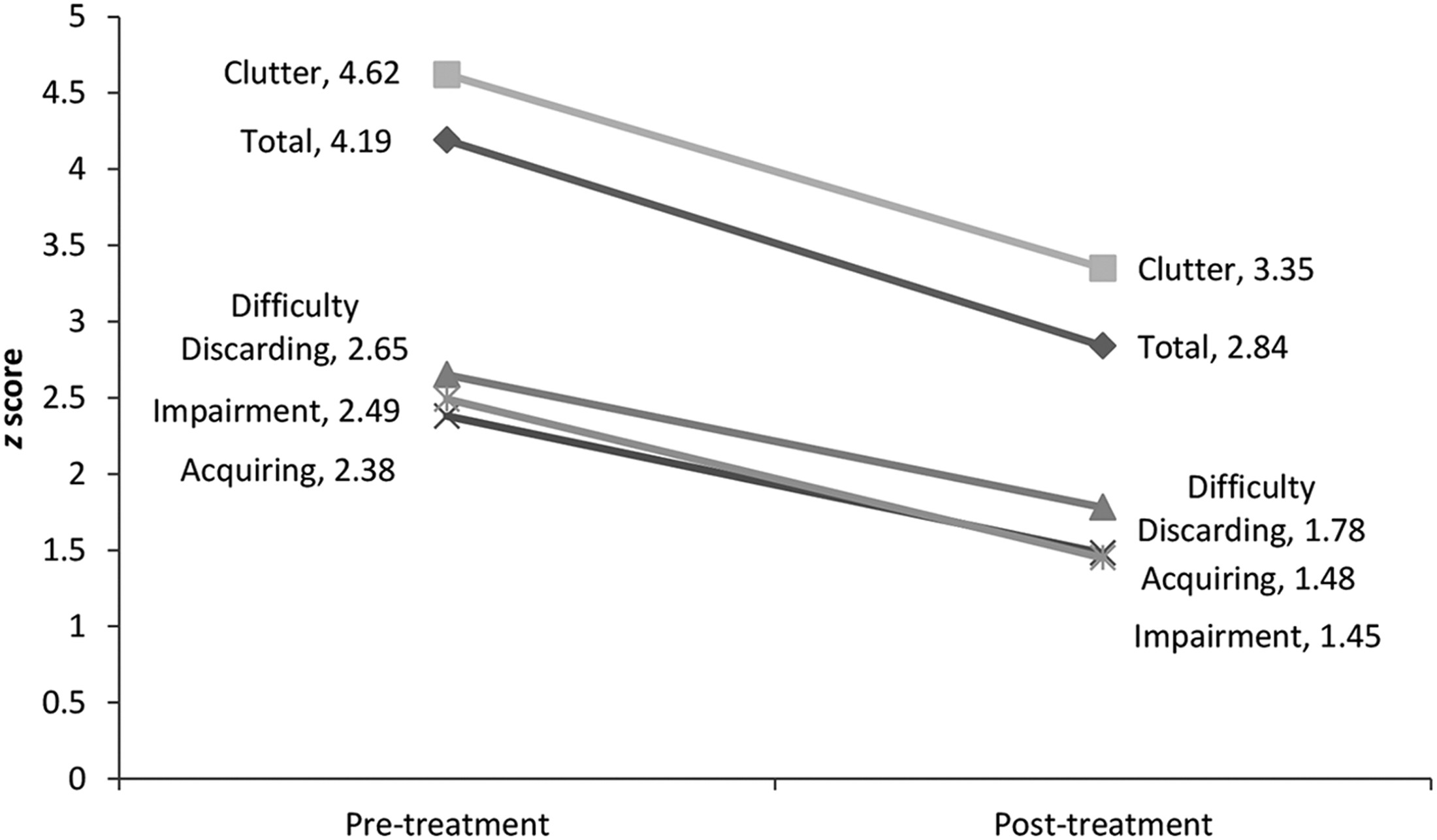

The present results demonstrate that CBT has a large effect from pre- to posttreatment, with a particularly strong effect for the core behavioral feature of HD, difficulty discarding. This is perhaps not surprising, given the focus of most of the CBT protocols on that symptom.

[1] Interestingly, a greater number of sessions in the home was associated with greater improvement in difficulty discarding. This likely reflects the fact that in-home sessions provide an opportunity to practice discarding in the most challenging context.

Effect sizes for clutter and acquiring were somewhat lower. As clutter is an environmental outcome of HD, one might expect that clutter would respond less strongly to behavioral intervention than would hoarding-specific behaviors. Indeed, the association between clutter reduction and more sessions (both in the office and in the home) would suggest that clutter reduction is a timeconsuming and laborious process. Follow-up data do not indicate that clutter continues to decrease after treatment discontinuation,

[48] although it could be argued that additional improvement would have occurred with ongoing external support. Additional research is needed to determine whether longer-term practical supports, such as help with sorting and organizing, or physical help with cleaning, would improve the efficacy of treatment on reducing clutter in patients who have received CBT.

The lower response of acquiring is somewhat surprising. The somewhat attenuated effect for acquiring may be due in part to the lower pretreatment severity in this domain, compared to clutter and total HD severity. The lower pretreatment score might also help explain why a higher percentage of patients met criteria for clinically significant change on acquiring symptoms compared to clutter. It is also possible, however, that the CBT protocols used in previous clinical trials

[1] placed a greater emphasis on discarding than on acquiring; recent manuals

[2] increase attention to reducing acquiring.

Functional impairment showed an effect that, while significant, lagged behind the effects observed for the core features of HD. As was the case with acquiring, this could be due in part to somewhat lower pretreatment severity on impairment measures. The attenuated effect on impairment may also relate to the ongoing impact of clutter, as the ADL-H is a hoarding-specific measure of impairment that explicitly links functional impairment to clutter in the home. As was the case with clutter, impairment appears to respond to a higher number of sessions in and out of the home. It is also quite possible that the level of impairment in HD patients is not exclusively due to the symptoms of HD themselves. Although impairment did not correlate significantly with depression across studies, other symptoms could be involved. Psychiatric comorbidity in HD is very high, with a majority of individuals meeting criteria for comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders.

[15] Furthermore, substantial evidence suggests the presence of diminished cognitive functions, such as attention, memory, or executive functions;

[49] impaired behavioral self-control;

[50] and significant medical illness.

[27,51] The SDS, which is a broader measure of impairment, does not specify a cause of impairment, and it may be that these other factors contribute to residual functional impairment even after successful treatment of HD symptoms.

The clinically significant change findings suggest that although treatment gains may be substantial in HD patients, the majority continue to score in the clinical range at posttreatment. The best results were seen for acquiring and impairment, which, as described previously, may relate to somewhat lower pretreatment severity on these measures. Clinically significant change was lowest in the domain of clutter, which also showed the highest severity at pretreatment. This finding, along with the somewhat weaker within-group effect size, underscores the idea that successful decluttering may require, for many, more time and intervention beyond that represented in most CBT trials.

The relationship between gender and CBT outcome was not expected, as gender has not been consistently associated with outcome in treatment for related disorders, such as OCD.

[52] Previous research investigating gender differences in HD has not produced likely explanations for the poorer CBT response in men: compared to women with HD, men with HD have somewhat higher rates of OCD, but lower rates of anxiety and mood disorders, and the rate of personality disorders is similar for both genders.

[15,53] Gender does not appear to be associated with the severity of HD symptoms or associated functional impairment,

[27] nor are men with HD described as less insightful than women with HD.

[53,54] Men with HD report a somewhat earlier age of onset than do women,

[53] although their HD is not more severe.

[55] In the present analysis, men treated for HD showed lower symptoms of difficulty discarding and acquiring symptoms (the behavioral aspects of HD), compared to women. Further research is needed in order to understand why men with HD may fare more poorly in CBT than do women, and how CBT might be modified in order to improve response rates in men.

Younger age was predictive of better CBT response, and it appears that this finding is largely the result of differential acquiring outcomes. Compulsive buying behaviors are more common among younger adults than among older adults,

[56] and the present data show that pretreatment acquiring was more severe among younger study patients. It may also be the case, however, that increased age presents a different set of challenges in CBT for HD. Older adults with HD may be at particular risk for chronic medical illness

[51] and executive dysfunction.

[57] Research in middle-to-later adulthood HD patients suggests that older age is not significantly associated with greater hoarding severity, depression, or functional impairment, although therapists rated older HD patients as more severely psychiatrically ill in general than younger patients.

[58] Further research on the impact of age on CBT response in HD, including potential remediation for cognitive dysfunction,

[59] is needed.

The finding that psychiatric medication use was associated with better outcomes in difficulty discarding is intriguing. Without knowledge of the specific medications used, it would be premature to speculate about a possible augmenting effect of medications on CBT for HD. In one open trial of paroxetine, hoarding and nonhoarding OCD patients fared equally well,

[28] although neither group showed a particularly strong response. In a recent open trial of venlafaxine, patients’ hoarding symptoms improved significantly with a high response rate.

[60] However, among OCD patients, those with hoarding symptoms show poorer response to pharmacotherapy.

[11] In the present analysis, samples with a higher rate of medication use were associated with higher levels of pretreatment impairment, potentially creating greater room for clinical improvement. Additional research is needed to compare the efficacy of CBT and medications for HD, alone and in combination.

The absence of demonstrated relationships between treatment outcome and the requirement of an HD diagnosis, therapist involvement, or individual versus group treatments merit further study. At this time the significance of these null findings is not clear, given the relatively small number of studies and the fact that categorical analyses such as these may have been underpowered.

Although the present study examined several potential moderators of treatment outcome, there are several other variables that have not been consistently assessed (and therefore could not be included in the present meta-analysis), but might nevertheless prove important as moderators or mediators of treatment response in HD. Factors such as poor insight,

[53,61,62] impaired cognitive function,

[15],

[63–67] and maladaptive personality features

[68–72] may all adversely impact the process and outcome of CBT.

A major limitation of the present meta-analysis is the use of within-group, rather than between-group, analyses. Without direct comparison to placebo conditions, treatment effects cannot be reliably distinguished from the passage of time, regression to the mean, and nonspecific treatment effects. To date, three randomized controlled trials of CBT have been published;

[5,8,21] in each of these, CBT proved superior to control conditions in which patients showed minimal improvement. The present analyses are confined to posttreatment outcomes, as there have been few follow-up studies of CBT for HD. The existing research, however, suggests that treatment gains are largely maintained after treatment discontinuation.

[48] We also did not include studies in which CBT was combined with alternative treatments. Two studies suggest that various forms of cognitive remediation, when added to CBT, might have a beneficial impact on cognitive function

[73] or on HD severity.

[59]