Combination pharmacotherapy—sometimes derisively called

polypharmacy to connote drugs that are deemed unnecessary or inappropriate in a regimen—has long been a cornerstone of treatment for complex medical conditions ranging from hypertension to infectious disease to oncology. Psychiatry has lagged behind other areas of medicine by fostering the idea that psychiatric disorders somehow ought to be treatable with only one medication, no matter how complex the problem may be, and that the deliberate juxtaposition of two or more drugs likely reflects shoddy prescribing rather than the pursuit of pharmacodynamic synergy. In the case of bipolar disorder, in which comorbid conditions are more common than rare (

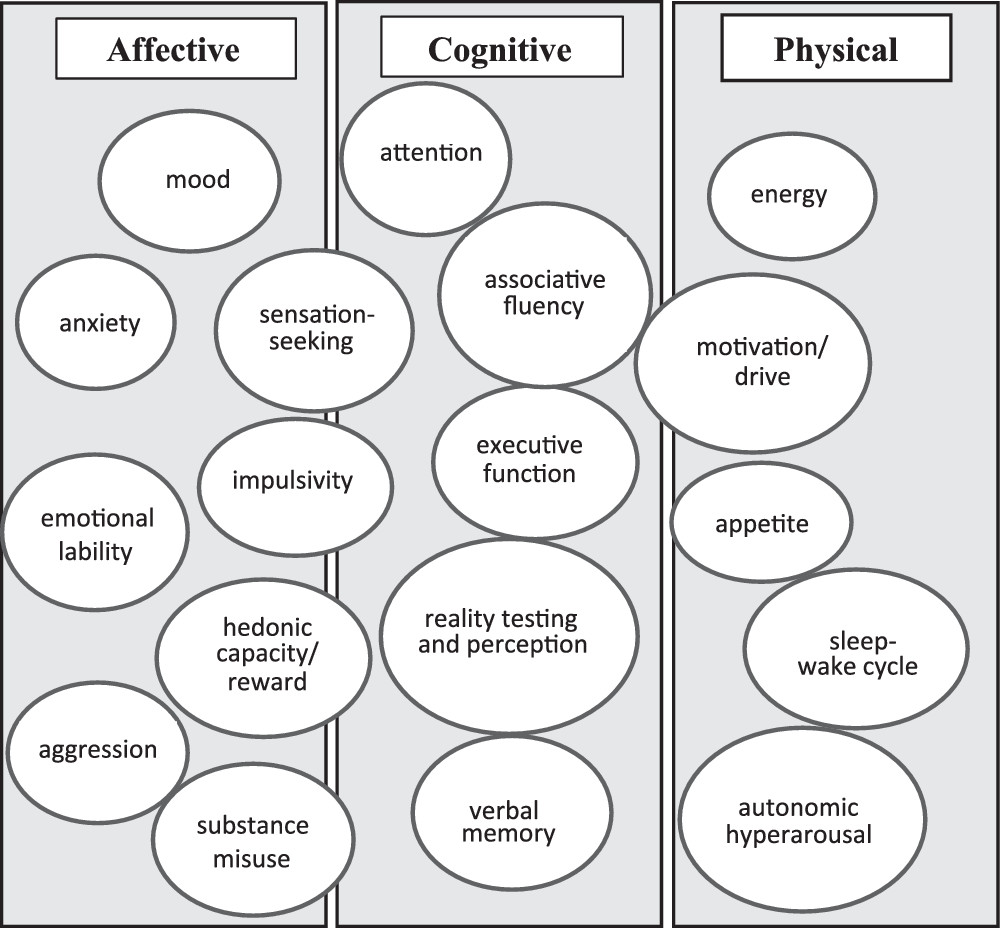

1) and symptom targets are often heterogeneous, the idea that one medication will reliably and effectively resolve all features of a complex clinical presentation is often unrealistic and naïve. In part, such fanciful expectations reflect a dubious assumption that a single underlying neurobiological process accounts for the entirety and diversity of psychopathology features shown by people with bipolar disorder. Seldom does one all-encompassing intervention ameliorate all signs of psychopathology as comprehensively as an antibiotic for pneumonia treats cough, fever, weakness, and dyspnea or a nitrate for angina eliminates chest pain, nausea, diaphoresis, and weakness. Accordingly, in this article, I provide an overview of the varied symptoms of psychopathology for which patients with bipolar disorder are prescribed medications so that practitioners can devise regimens that are complementary, nonredundant, purposeful, and evidence based.

Prevalence of Prescription of Complex Combination Pharmacotherapy

Cross-sectional descriptive studies have suggested that about one-fifth (

2) to one-third (

3) of patients with bipolar disorder are taking four or more psychotropic medications at the time of hospitalization. Among 4,035 mostly outpatient entrants to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD), 18% were taking four or more psychotropic drugs, and 40% took three or more (

4). One European study found that nearly 80% of outpatients with bipolar disorder took a mean of 3.8 medications, most often a mood stabilizer (92%), followed by an antidepressant (59%), benzodiazepines (43%), antipsychotics (39%), and thyroid hormone (21%;

5). Another report from the United Kingdom found that, in 2009, nearly half of patients with bipolar disorder were prescribed two or more psychotropic drugs on an ongoing basis; nearly half of that group chronically took lithium plus an antipsychotic drug (

6).

Separate from merely counting how many medications a patient takes is determining whether the components of a pharmacotherapy regimen are appropriate and complementary (as opposed to inappropriate and pharmacologically conflictual). Considerations of drug appropriateness include the following:

•

Is the intended use of a drug aligned with its known pharmacodynamic effects? For example, lamotrigine would not be considered relevant to treat acute mania; chronic sleep aids may be unnecessary and counterproductive in patients with hypersomnia.

•

Are the known pharmacodynamic effects of a drug contrary to current symptoms? Antidepressants generally have no value during acute mania; and psychostimulants are likely counterproductive when treating acute psychosis.

•

Do the effects of one drug contradict or conflict with those of another? An example is simultaneous use of an anticholinergic drug (such as benztropine) and a procholinergic drug (such as donepezil).

•

Are current medications consistent with the patient’s present clinical state? Antidepressants would be illogical during acute mania, as would be the absence of one or more antimanic drugs.

•

Are adverse effects of one drug causing or mimicking psychiatric symptoms? Akathisia can be mistaken for agitation; anticholinergics impair cognitive function; and sleeplessness or loss of libido can be caused by a monoaminergic antidepressant or by depression. Adverse effects may also exacerbate a medical problem (e.g., beta blockers worsening asthma; noradrenergic drugs driving hypertension).

•

Are medications being retained if they have been deemed ineffective (and have all medications in a regimen received an adequate trial and been deemed effective or ineffective)?

•

Are medications being used and retained even when they have an abundance of negative controlled trial data for an intended purpose, such as topiramate or gabapentin in mania or paroxetine in bipolar depression, or an illogical rationale, such as use of modafinil or amphetamine for agitation or anxiety?

•

Have clinically important drug interactions gone unrecognized? For example, carbamazepine and primidone are potent inducers of cytochrome P450 enzymes and may effectively reduce serum levels and pharmacodynamic efficacy of drugs that undergo Phase I oxidative metabolism.

Do Guidelines Offer Guidance?

Practice guidelines convey only limited insight into the utility of complex combination therapy. Beyond specifying episode features such as with versus without psychosis or mixed versus pure affective polarity, they tend to say little about contexts and comorbid conditions that typically influence treatment decisions. Examples might include mania in someone with or without metabolic syndrome, in someone with or without substance misuse, or in a sexually active woman of child-bearing age or a person with bipolar depression with versus without prominent anxiety, with comorbid ADHD, or with suicidal features. For a patient with severe, acute mania, some guidelines advocate a combination of two drugs (usually lithium or divalproex plus an antipsychotic) as a first- (

7–

9) or second- (

10) line intervention. Some make no specific mention of combining three or more agents in any phase of bipolar disorder so much as replacing an ineffective medication with an alternative (e.g., the 2018 Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments Guidelines;

8). Others identify triple (or greater) therapy regimens as worthy of consideration only after the failure of multiple single- or dual-drug therapy efforts for manic or mixed episodes (e.g.,

9,

10), and these regimens usually consist of two mood stabilizers plus a first-generation antipsychotic or a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA).

For acute bipolar depression, current guidelines have not suggested a role for more than two drugs in combination (generally a mood stabilizer or SGA plus an antidepressant). Guidelines usually list novel agents (such as pramipexole [

11], inositol [

12], anti-inflammatory or antioxidant drugs [

13], or thyroid hormone [

14]) collectively as last-step options, but without regard to the total net number of medications in a regimen. Most also seldom offer explicit recommendations about when and how to di

scontinue a drug once it has been introduced into a regimen, apart from often blanket discouragement of long-term use of antidepressants for people with bipolar disorder (despite a lack of consensus among experts and a limited evidence base from which to inform decisions about deprescribing antidepressants when they are acutely effective;

15).

No systematic studies have looked at combining two (or more) monoaminergic antidepressants that have complementary mechanisms as a strategy to treat bipolar depression, unlike for major depressive disorder. The relatively small handful of randomized trials that have involved the use of traditional antidepressants to treat bipolar depression have generally not demonstrated robust efficacy—not unlike for treatment-resistant unipolar depression. However, with no studies of the use of combination antidepressants in treating bipolar depression, the potential utility of novel or multiple antidepressant approaches remains unknown. Clinical characteristics associated with the use of combination therapy for bipolar disorder are summarized in

Table 1 (

2–

4,

16–

18).

Polypharmacy has been identified as one of the biggest contributors to guideline-discordant treatment of bipolar disorder (

18), yet herein lies a major dilemma for practitioners: Guideline recommendations are based on traditional efficacy trials for specific phases of an illness rather than on effectiveness studies with real-world populations. Snippets of guideline recommendations can be judged for concordance with prescribed medications for specific illness phases of bipolar disorder (e.g., in the STEP-BD, guideline-concordant treatments were prescribed for more than 80% of manic-hypomanic, mixed, or depressive episodes per se;

19), but most patients with bipolar disorder outside of clinical trials require treatment for more than simply a current affective phase of illness. Clinician surveys that examine guideline nonadherence in treating bipolar disorder have pointed to the failure of guidelines to address particular features of unique clinical populations (

20). Indeed, it would be difficult to craft an effective guideline-driven drug regimen for a bipolar II depressed patient with prominent anxiety, attentional complaints, substance use comorbidity, chronic suicidal ideation, metabolic syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea, and chronic kidney disease.

Guidelines become less useful when diagnoses and illness phases do not conform neatly to DSM-5 criteria, patient priorities drive adherence, and prominent comorbid conditions and complex features (e.g., trauma histories) must be addressed. In addition, the clinical trials literature does not indicate whether and when mono- or dual pharmacotherapies yield better outcomes than more extensive but thoughtfully devised combination regimens is largely unknown. The shortcomings of current practice guidelines for bipolar disorder are summarized in

Box 1.

Rationales for Pharmacotherapy Combinations

From one perspective, combining diverse medications makes sense with a disease entity in which known drug mechanisms of action are complementary and related to the pathophysiology of the underlying disease process. In the case of bipolar disorder, such exactitude is unfortunately largely unknown and may at best be speculative. Although a systematic review of current theories about the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder is beyond the scope of this article, theories that have been reviewed elsewhere (e.g., Manji et al. [

21]), ranging from the level of molecular-intracellular function to neuronal networks, include the following: monoaminergic dysregulation; elevated intracellular calcium and abnormal calcium signaling (e.g., calcium channel blockade); circadian dysrhythmias (e.g., light entrainment of the circadian pacemaker; sleep-wake cycle perturbations); dysfunction of purine metabolism (hyperuricemia in mania); endocrinopathies (e.g., glucocorticoid receptor dysfunction, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical dysregulation, hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis dysfunction); abnormal signal transduction (e.g., overactive inositol phosphate signaling, elevated intracellular inositol or cyclic adenosine monophosphate); immuno-inflammatory mechanisms, impaired neuronal plasticity, regulation of oxidative stress, and neuroprotection against neuronal loss; and disrupted connectivity of neural circuits.

Table 2 summarizes presumed neuronal and molecular-cellular mechanisms of action for psychotropic drugs commonly used to target mania, depressive symptoms, or both in patients with bipolar disorder (

22–

55). The list of potential mechanisms is far from complete due to the limited knowledge about bipolar disorder’s basic pathophysiology, along with emerging novel hypotheses that do not yet clearly translate to any specific biological interventions (e.g., mitochondrial dysfunction, shortened telomere length).

In addition, as noted in the table and its footnotes, in many instances only preliminary animal or in vitro data exist regarding the effects of specific psychotropic drugs on possible receptor targets; these effects may not be so straightforward or easily translated. For example, neither lithium nor anticonvulsant mood stabilizers exert known direct effects on specific serotonin receptors, but they might exert indirect modulating effects; possible in vitro effects of monoaminergic antidepressants on ion channels may not translate to pharmacodynamic effects in humans. Preclinical or in vitro receptor binding studies may not necessarily provide information about regional anatomical differences in drug effects. Existing treatments, for better or worse, are geared more practically toward altering observable psychopathology rather than modifying an identified neurobiological process.

Some proposed mechanisms are likely more specific to the treatment of depression than to that of mania (e.g., serotonin reuptake inhibition) or vice versa (e.g., protein kinase C inhibition or inositol depletion), and even identified neuronal or molecular mechanisms do not necessarily provide information about pharmacodynamic class effects (e.g., mania may respond to some drugs that inhibit protein kinase C inhibitors [e.g. tamoxifen;

56], but not all [e.g., omega-3 fatty acids;

57]). Existing knowledge about drug mechanisms of action also does not specifically address pharmacodynamic effects relevant to particular illness subcomponents (e.g., use of a drug for narrow purposes such as putative antisuicide effects, such as lithium [

58]), procognitive effects (e.g.,

withania somnifera [

59] or lurasidone [

60]), anticraving effects (e.g., naltrexone), or targeting of impulsive aggression (e.g., divalproex;

61). It is also worth noting that nuanced differences exist within the broad mechanisms included in

Table 2 whose depth is beyond the scope of this article. For example, some anticonvulsant drugs (divalproex, carbamazepine) are believed to exert antiglutamatergic effects only through

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor blockade, whereas others (lamotrigine) appear to also affect α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors. Calcium channel blocking effects of mood-stabilizing anticonvulsants may occur through L-type calcium channels (carbamazepine); L- and T-type calcium channels (divalproex); or L-, P/Q-, R-, and T-type calcium channels (lamotrigine). Among SGAs, individual agents vary in their specific receptor profiles and affinities, as well as in their unique targets (e.g., 5-HT7 antagonism or D3 partial agonism are not universally shared targets across SGAs, as noted in

Table 2).

Complex Combination Pharmacotherapy for Bipolar Disorder and Clinical Outcomes

Almost no systematic studies have provided information about whether and when a more extensive pharmacotherapy regimen leads to a better or worse clinical outcome than a simpler regimen. Such questions may never be answerable because of the inherent complexities of controlled study designs and the matching of drug regimens to individual patient characteristics that in themselves influence medication choice. It is obviously also an oversimplification to count the sheer number of medications someone takes without regard to the appropriateness, responsivity, redundancies, and purposefulness of each drug on a treatment roster, as though counting instruments in an orchestra without distinguishing woodwinds from brass or strings or the composition of the overall ensemble. Specific medication choices in a given regimen, and their response likelihoods, are also often made not just on the basis of an overall Food and Drug Administration indication (e.g., acute mania) but more precisely according to other characteristics associated with more specific symptom domains (e.g., divalproex vs. lithium in mixed episodes; lamotrigine for maintenance therapy in patients more prone to depressive rather than manic recurrences) (

62).

Existing randomized combination pharmacotherapy trials for bipolar disorder focus mainly on the potential utility of two medications versus one during either acute manic or depressive phases of illness or during maintenance and relapse prevention phases. This literature is summarized in

Tables 3-

5, respectively, (

63–

88) for treatment of acute bipolar manic or mixed episodes, acute bipolar depression, or bipolar maintenance and relapse prevention, respectively. For acute bipolar depression,

Table 4 focuses on combinations of mood stabilizers or adjunctive SGAs with mood stabilizers; I did not include studies of traditional antidepressant or novel compounds (e.g., pramipexole, modafinil, psychostimulants) added to a mood stabilizer because such published studies generally do not account for variability in inherent potential antidepressant properties among mood stabilizers.

Some naturalistic studies have suggested that patients with bipolar disorder who take fewer medications (e.g., one) manifest more symptom stability (remain relapse-free) over time than those on two, three, or more medications (

5,

89); still others have suggested that when medication regimens include certain core pharmacotherapies such as lithium, there may be less need to add additional medications (

90). Open (nonrandomized) data suggest that inpatients with mania who begin pharmacotherapy with a combination of lithium and divalproex at the outset may incur a lesser dosage burden of antipsychotic cotherapy than those who begin on lithium without divalproex (

91). The NIMH Lithium Treatment Moderate Dose Use Study (LiTMUS) trial found that cotherapy with subtherapeutic doses of lithium has not shown greater symptomatic benefit than placebo (although a post hoc analysis suggested that low-dose adjunctive lithium may be associated with lower dosages of concomitant SGAs;

92). By contrast, use of other medications (notably, chronic benzodiazepine use) in a regimen for treatment of bipolar disorder may be associated with higher recurrence rates and more severe overall illness (

93)—not necessarily in a causal fashion, but more likely because of the stigmata of pathology.

The literature on extensive polypharmacotherapy of psychotropic drugs is largely more naturalistic and observational than randomized, which makes it hard to draw causal inferences about treatment outcomes. In such studies, medications are usually chosen on the basis of patients’ individual conditions, leading to the problem of confounding by indication. For example, some observational studies have attributed lower suicide attempts or completions to the inclusion of lithium in a treatment regimen over other mood stabilizers (

94), but these studies have not accounted for the possibility that clinicians might avoid prescribing lithium to patients at a higher risk of suicide (e.g., in the aftermath of an overdose or other attempt), relegating prescription of lithium to a potential marker or artifact of a better prognosis at baseline. Similarly, some observational studies of rapid cycling have concluded that prescription of antidepressants may lead to more frequent episodes (

95), without considering the reverse possibility that frequent depressive episodes may cause more prescription of antidepressants. In any nonrandomized pharmacotherapy study (but especially in those involving multidrug regimens), possible confounding by indication poses obstacles to inferring causal drug effects as a result of unrecognized and unaccounted-for moderators and mediators of outcome (

62).

A further dilemma when trying to assess extensive combination pharmacotherapy regimens involves uncertainties about within-class differences versus generalizabilities among medications. For example, the relative magnitude of antimanic efficacy across individual SGAs appears comparable (

96), although individual agents may vary in their antidepressant, anxiolytic, or tolerability profiles. Similarly, monoaminergic antidepressants are often lumped together as homogeneous entities, although the absence of placebo-controlled studies for most newer agents (vortioxetine, vilazodone, desvenlafaxine, levomilnacipran, mirtazapine) makes it difficult to generalize about within-class efficacy or the potential for synergy from particular antidepressant combinations.

What About Antidepressant Adjuncts to Mood Stabilizers for Bipolar Disorder?

Practice guidelines (

7,

8,

10) and expert consensus statements (

15) emphasize the importance of avoiding antidepressant monotherapies in bipolar I depression (with possibly greater leniency in bipolar II depression). Such recommendations mainly reflect concerns about the potential for antidepressants to destabilize mood via a treatment-emergent affective switch (TEAS). Consequently, guidelines have advised using antidepressants only in tandem with mood stabilizers in bipolar depression, mainly on the basis of assumptions that mood stabilizers help safeguard against TEAS outcomes rather than the perception that most mood stabilizers exert meaningful intrinsic antidepressant effects that synergize with antidepressant cotherapies. One often cited example, the NIMH STEP-BD study, found only a modest antidepressant response rate with mood stabilizer monotherapy (about 24%) and no added benefit with antidepressant cotherapy (

97). Said differently, the current evidence base has suggested that neither mood stabilizers nor monoaminergic antidepressants, nor their combination, exert reliable and robust antidepressant effects on bipolar depression. Yet, contemporary observational studies have found that about one-third of patients with bipolar disorder take antidepressants on a long-term basis (>90 days) as part of their overall pharmacotherapy regimen (

98). Such prescribing habits notwithstanding, the Florida Medicaid Guidelines (

9) noted that “there is inadequate information (including negative trials) to recommend adjunctive antidepressants . . . for bipolar depression.”

It is also worth noting that clinicians in real-world practice settings may sometimes use selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or other antidepressants for their putative anxiolytic properties (in addition to, or possible entirely apart from, depression as an intended treatment target). However, apart from one secondary analysis from a negative randomized controlled trial of paroxetine for bipolar depression (

99), no prospective randomized trials have demonstrated anxiolytic efficacy for monoaminergic antidepressants in bipolar disorder. Although this absence of evidence is not evidence of absence and does not negate the possibility of benefit, prescribers must recognize that such assumptions have not been empirically tested.

Deprescribing and Maintenance of Pharmacological Hygiene

Surprisingly few randomized pharmacotherapy discontinuation trials exist in research on bipolar disorder. Although such studies provide the most rigorous data about the optimal treatment duration for any medication, that information is especially important during combination therapies, in which unnecessarily prolonged inclusion of a drug jeopardizes overall treatment adherence and imposes an additive side effect burden, cost, and risk for drug-drug interactions. To the extent that randomized clinical trials nowadays fall mainly under the auspices of pharmaceutical industry sponsorship, there is little economic incentive for commercial manufacturers to drive the deprescribing of their products.

Give the scarcity of empirical information about when a particular cotherapy may no longer be beneficial or necessary, the components of a pharmacology regimen can potentially accrue in a manner sometimes akin to hoarding. Because pharmacotherapy per se is for most patients with bipolar disorder an indefinite, open-ended undertaking, it can be difficult to fathom specified end points for stopping certain medications within a regimen. One conspicuous exception is the frequent admonition against long-term antidepressant use espoused in some practice guidelines, based on theoretical concerns about accelerated cycling frequency. In fact, however, randomized discontinuation trial data would suggest that, contrary to popular belief, cessation of an antidepressant after an initial robust response may incur a greater risk for depression relapse (

103,

104), except in patients with past-year rapid cycling, for whom long-term antidepressant use has been associated with more depressive episodes (

104).

Rapid cycling may represent a particular instance in which monotherapy may rarely produce improvement. A notable example is a randomized trial specifically with patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder (

105) in which open-label dual therapy with lithium plus divalproex was then converted to monotherapy with either agent. Only one-quarter of 254 rapid-cycling patients initially stabilized during combination therapy with lithium plus divalproex (meaning that most rapid-cycling patients either poorly tolerated or did not benefit from this combination); after subsequent randomization to either agent as monotherapy, only about half of patients remained relapse free over a 20-month period. Unfortunately, this study did not examine whether the continued combination of lithium plus divalproex might have prolonged the time until relapse more than occurred with either pharmacotherapy. It also did not examine whether the total number of relapses per year among rapid-cycling patients was less after randomization to either monotherapy than before.

In the case of adjunctive SGAs, Yatham and colleagues (

106) studied patients with manic or mixed bipolar episodes who were stabilized on lithium or divalproex plus an SGA (olanzapine or risperidone) and then compared time until relapse among those randomized to continued combination therapy versus mood stabilizer monotherapy for one year. Relapse rates were significantly lower for those in the combination condition than in the monotherapy condition (hazard ratio=0.53, 95% confidence interval=0.33–0.86) up to 24 weeks, but beyond that time frame the combination provided no continued advantage in preventing relapse over monotherapy. However, weight gain was significantly greater with a continued adjunctive SGA beyond this time (mean 3.2 kg gain vs. ≤0.1 kg gain, respectively).

A basic principle of psychopharmacological hygiene involves discontinuing a psychotropic drug that exerts no benefit after an adequate trial has elapsed. More ambiguous can be knowing whether and when to stop ancillary pharmacotherapies for bipolar disorder, such as benzodiazepines or sleep aids, nonbenzodiazepine anxiolytics (buspirone, hydroxyzine, anxiolytic anticonvulsants), psychostimulants (particularly if used off label to counteract sedation, obesity, or slowed attentional processing), beta blockers for social anxiety or tremor, thyroid hormone in the absence of intrinsic thyroid disease (or safety concerns related to cardiac arrhythmias or osteoporosis), and vitamins or nutritional supplements.

Other tenets of basic pharmacological hygiene include avoiding mechanistic redundancies, contradictory mechanisms, and irrational strategies to avoid future events (e.g., maintaining antidepressants during an acute manic episode on the basis of the notion that doing so may ward off a subsequent depression); optimizing dosing of a first drug before adding additional agents aimed at the same intended symptom target; not maintaining sleep aids when hypersomnia is present; minimizing the number of new or additive drug exposures during pregnancy, to the extent feasible; and knowing why a prescribed drug was originally introduced to a regimen and addressing its utility and ongoing relevance for a given patient.

As a practical matter, it can be helpful (as well as rapport building) for patients and clinicians to conduct periodic “performance evaluations” of a pharmacotherapy regimen and review and mutually decide what value and cost each drug brings to the patient’s treatment. Medications whose relevance is uncertain can then be further assessed one by one (thus changing only one variable at a time), either by tracking intended target symptoms more closely and formally or by dosage reduction or cautious elimination to determine whether a unique benefit indeed exists.

Another useful practical rule of thumb involves the concept of making no changes to a drug regimen for at least four to six months once unequivocal wellness has been established. This approach may also sometimes include prolonging or suspending a cross-taper in progress. Although “stalled” cross-tapers can leave patients on potentially unnecessary or duplicative medications, and as such are less than elegant, greater gains are sometimes accomplished by changing nothing once wellness is achieved and letting patients accrue lengthier periods of euthymia before embarking on efforts to prune a drug regimen.

The four- to six-month time frame corresponds to the conventional time period that defines recovery, as noted by nomenclature task forces of both the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (

107) and the MacArthur Foundation (

108). Symptoms that arise within this time frame after remission from an acute episode are generally recognized as signs of relapse (i.e., the index episode itself reignites), and symptoms that emerge beyond four to six months of wellness are considered signs of a recurrence (i.e., a new episode). Statistically, survivorship of four to six months of wellness after an index episode categorically places someone at a lesser risk for clinical deterioration and consequently represents a logical and potentially safer time to ask whether a particular component of a regimen is or is not actually necessary to sustain wellness.

Future Directions

Several important unmet needs exist for which further studies and guidelines can advance knowledge and clinical practice about complex combination pharmacotherapy for patients with bipolar disorder. These needs include examining sequential pharmacotherapies and specific augmentation-versus-replacement strategies among patients whose responses to core mood stabilizer monotherapies are inadequate; undertaking randomized discontinuation trials to determine whether and when a particular medication has a finite optimal duration of benefit (and at what point diminishing returns might be expected); and conducting formal studies designed specifically to treat common conditions that are comorbid with bipolar disorder, including anxiety disorders; alcohol and substance use disorders; and adult ADD, ADHD, and cognitive dysfunction. Such comorbid conditions contribute to combination pharmacotherapy, but the dearth of dedicated studies targeting such presentations severely limits the evidence base for differential therapeutics.

Other needs are identification of factors and clinical circumstances in which augmentation strategies versus switching from one drug to another produces better outcomes and testing hierarchical treatment approaches as a means to ultimately simplify pharmacotherapy regimens in complex or comorbid presentations. For example, in the case of bipolar disorder with comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder, some authors have argued that optimization of mood stabilizers can adequately treat both conditions, obviating the necessity of SSRI cotherapy (

109); in the case of mood disorder with concurrent alcohol use disorder, further studies are needed to determine whether and when pharmacotherapy of mood symptoms alone may simultaneously reduce excessive drinking (

110).