Although there is evidence of increased risk of adverse effects and a consistent association with inpatient admission, the practice of combining antipsychotics is broadly used and appears to be effective for a subgroup of patients. Correll et al. (

18) performed a meta-analysis of patients with schizophrenia (N=1,216) on antipsychotic polypharmacy (mean±SD duration of 12±11.3 weeks) from 19 studies (double-blind, single-blind, open, and unclear blinding) performed in China, the United States, Japan, Israel, Turkey, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Both monotherapy and combination therapy arms included patients receiving both first- and second-generation antipsychotics, with the combination therapy including either oral or long-acting injectable drugs. The most commonly prescribed drugs were clozapine, chlorpromazine, risperidone, and sulpiride. Although the studies had a variety of outcomes, combination therapy was more effective than monotherapy, and more patients dropped out of the monotherapy groups than the combination antipsychotic groups. The combination therapy was more effective when treatment lasted longer than 10 weeks, when one of the antipsychotics was clozapine, and when treatment was initiated simultaneously with both antipsychotics, rather than when a second antipsychotic was added because of a lack of response. In regard to antipsychotic classes, combinations of a first- and second-generation antipsychotic were significantly more effective than monotherapy with either class. It is notable that in the studies conducted in China, clozapine was frequently prescribed in combination with other antipsychotics, and the combinations were initiated at the start of the trial rather than adding the second antipsychotic because of a lack of response to monotherapy.

Foster et al. (

20) compared the long-term (30-month) outcomes in time to relapse and clinical measures among patients who were initially on combination antipsychotics (N=50), on long-acting injectable antipsychotic monotherapy (N=20), or on oral antipsychotic monotherapy (N=206), after randomization to either long-acting injectable risperidone or a second-generation oral antipsychotic. The patients in the oral antipsychotic group had significantly fewer hospitalizations than those on combination antipsychotics at baseline (p=0.009). At 30-month follow-up, 68% of patients who were initially on combination antipsychotics had relapsed, whereas only 53% of patients who were initially on a long-acting injectable antipsychotic and 52% of those who were initially on an oral antipsychotic had relapsed. Although a chi-square test (χ

2=3.85, df=2, p=0.146) showed no significant difference in the relapse rate among groups, the log-rank test showed a significant difference among the groups in time to first relapse (χ

2=6.81, p=0.033), with a significantly longer time to relapse among the oral antipsychotic group (mean=562.8 days) than among the combination antipsychotic group (mean=409.5, p=0.011). In this study, patients who were switched from an antipsychotic combination to monotherapy appeared more vulnerable to relapse.

Next, we present case examples that illustrate the common clinical situations leading clinicians to use an antipsychotic combination and comment on the evidence supporting this practice.

Case example 1: optimizing treatment for a psychosis domain not fully addressed by the initial drug.

Ms. X is a 37-year-old Hispanic woman with a history of schizophrenia with significant thought and behavior disorganization and multiple past inpatient admissions for bizarre behavior (e.g., trying to run through a store window, walking into traffic) motivated by command-type auditory hallucinations. Ms. X is not using birth control, has no known medical conditions, does not use drugs, and drinks alcohol only occasionally. When evaluated by a psychiatrist for a second opinion, she is pleasant and appears cooperative, but she is unable to offer a coherent history because of her loose thought process and bizarre, poorly formed delusions. Family reports that although Ms. X is able to take a shower, dress herself, and do some household chores, she has to be redirected to follow a daily routine. She was partially stabilized on 500 mg/day quetiapine and 50 mg/day sertraline without any notable weight gain or obvious metabolic adverse effect. However, she reports severe constipation from the current medication. She has not had an inpatient admission in the past six months. However, she remains disorganized and incoherent at times, with odd delusions. She cannot drive and is unable to conduct any social engagements without the assistance of her parents.

The consulting psychiatrist suggests clozapine and explains the agranulocytosis monitoring requirements and other possible side effects: seizures, orthostatic hypotension, cardiomyopathy, increased risk of cardiovascular events, and—highly relevant to this case—constipation. The patient and family decide not to pursue clozapine because of the perceived burden of blood draw. They are also reluctant to switch antipsychotics because they perceive that the quetiapine successfully reduced Ms. X’s admissions. The patient and her family choose to add paliperidone to quetiapine to address her thought disorder and hallucinations. The patient also looks forward to eventually taking a lower dose of quetiapine, which may limit its only perceived side effect of chronic constipation.

This case potentially illustrates Kapur et al.’s (

21) “kiss and run” hypothesis of quetiapine’s psychopharmacological action. Quetiapine is thought to have a low, apparently subtherapeutic, D

2 receptor occupancy 12 hours after administration. However, at four to six hours postadministration, the D

2 receptor occupancy measured with positron emission tomography is high, leading to the hypothesis that quetiapine dissociates from receptors faster than other antipsychotics (

21). Adding a low-dose antipsychotic with consistently high D

2 occupancy may be of utility in this case by addressing two domains of psychosis not fully addressed by the initial drug, namely the delusions and disorganized speech and behavior that continue to limit the patient’s function. In addition, paliperidone has minimal affinity for the muscarinic receptors, whose blockade is implicated in the side effects of constipation from antipsychotic medication (

22), thus maximizing treatment of Ms. X’s symptoms without exacerbation of the adverse effects she is currently experiencing.

Table 2 (

19,

22–

24) shows the receptor affinity of commonly used antipsychotics. The greater the number of plus signs, the stronger the affinity at that receptor. Antipsychotic combinations may also aim to optimize nondopaminergic (e.g., serotonergic, glutamatergic, and adrenergic) receptor occupancy to alleviate positive and negative symptoms (

13). Adding a second antipsychotic can also address the affective domain of psychosis (depression or mania), insomnia, or aggression toward self or others.

Current evidence shows that antipsychotic therapeutic action is more likely to occur after at least 60% occupancy of D

2 receptors is achieved; however, at 80% occupancy, the movement-associated adverse effects of antipsychotics are thought to begin (

25). When using multiple antipsychotics, the likelihood of surpassing the therapeutic window is higher and motor-adverse effects may occur, including extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and akathisia. Motor side effects of antipsychotic treatment are largely attributed to dopamine blockade, with contributions from the antipsychotic effect of other neurotransmitters, for example, D

2 blockade in the nigrostriatal pathway leading to Parkinsonism; dopamine blockade accompanied by acetylcholine, gamma‑aminobutyric acid, norepinephrine, serotonin, and neuropeptides in akathisia; and dopamine blockade and an increase in acute cholinergic activity in acute dystonia (

26–

28). Because the motor side effects of antipsychotics are rarely quantified in practice, they cannot be easily identified in the electronic medical record. In the absence of prospective studies addressing the motor side effects of antipsychotic combinations versus monotherapy, researchers have studied treatment with anticholinergic drugs prescribed concomitantly with antipsychotic combinations to generate data on the frequency of motor side effects. Generally, combinations that included first- and second-generation or two second-generation antipsychotics led to increased anticholinergic use, possibly reflecting increased motor side effects (

28). It can be argued that anticholinergic medications may be prescribed prophylactically and therefore do not reflect the presence of motor side effects. However, in either case, the addition of another medication with its own side effect profile can be considered to be a negative outcome for the patient (

26). Carnahan et al. (

26) noted that the low propensity of extrapyramidal side effects found with second-generation antipsychotic monotherapy does not persist when second-generation antipsychotic drugs are combined. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, which is thought to occur as a result of a marked and sudden reduction in central dopaminergic activity resulting from D

2 receptor blockade within the nigrostriatal, hypothalamic, mesolimbic, and mesocortical pathways, has been found to be associated with antipsychotic combinations, although this association has primarily been noted in case reports (

23). Currently, tardive dyskinesia and akathisia have not been clearly associated with combination antipsychotics (

28).

Dopamine blockade also can lead to a lack of inhibition of prolactin release. This in turn leads to hyperprolactinemia and in some cases galactorrhea, amenorrhea, sexual dysfunction, osteoporosis, and even breast cancer (

24). It appears that adding an antipsychotic drug with high D

2 blockage potential to a drug with low D

2 propensity increases the risk of hyperprolactinemia (

25). The apparent exception is the addition of aripiprazole, which has been shown to decrease prolactin levels and is a possible treatment for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia (

24,

29).

Case example 2: perceived difficulties in access and exposure to clozapine.

Mr. Y is a 56-year-old nonsmoking man with schizoaffective disorder who has had multiple depressed psychotic episodes, each leading to two- to three-week-long hospitalizations for paranoia and hostile behavior. He was discharged from his most recent hospitalization on 30 mg/day olanzapine and 40 mg/day fluoxetine. Despite good medication adherence, he was still depressed and at times had passive suicidal thoughts, paranoia, and auditory hallucinations with derogatory content. Eventually, he was switched from fluoxetine to amitriptyline, and his depressive symptoms resolved. He continued to have auditory hallucinations that interfered with his ability to perform activities of daily living and attend his peer-support program. He repeatedly refused clozapine monotherapy in inpatient and outpatient settings because of concerns about blood draw requirements and frequent trips to the pharmacy, even though his case manager offered to arrange home medication delivery. Eventually, Mr. Y’s outpatient psychiatrist offered to add fluphenazine to his regimen to address the hallucinations after a thorough discussion of possible motor side effects. The patient agreed to take fluphenazine and had remission of the hallucinations with 5 mg/day, while his fasting lipids, serum glucose, waist circumference, weight, and onset of involuntary movements were monitored. The patient became able to work 16 hours/week and consistently kept all his clinic appointments. However, he developed involuntary movements of his arms and trunk that, although manageable, did not resolve with further treatment.

Why not consider clozapine?

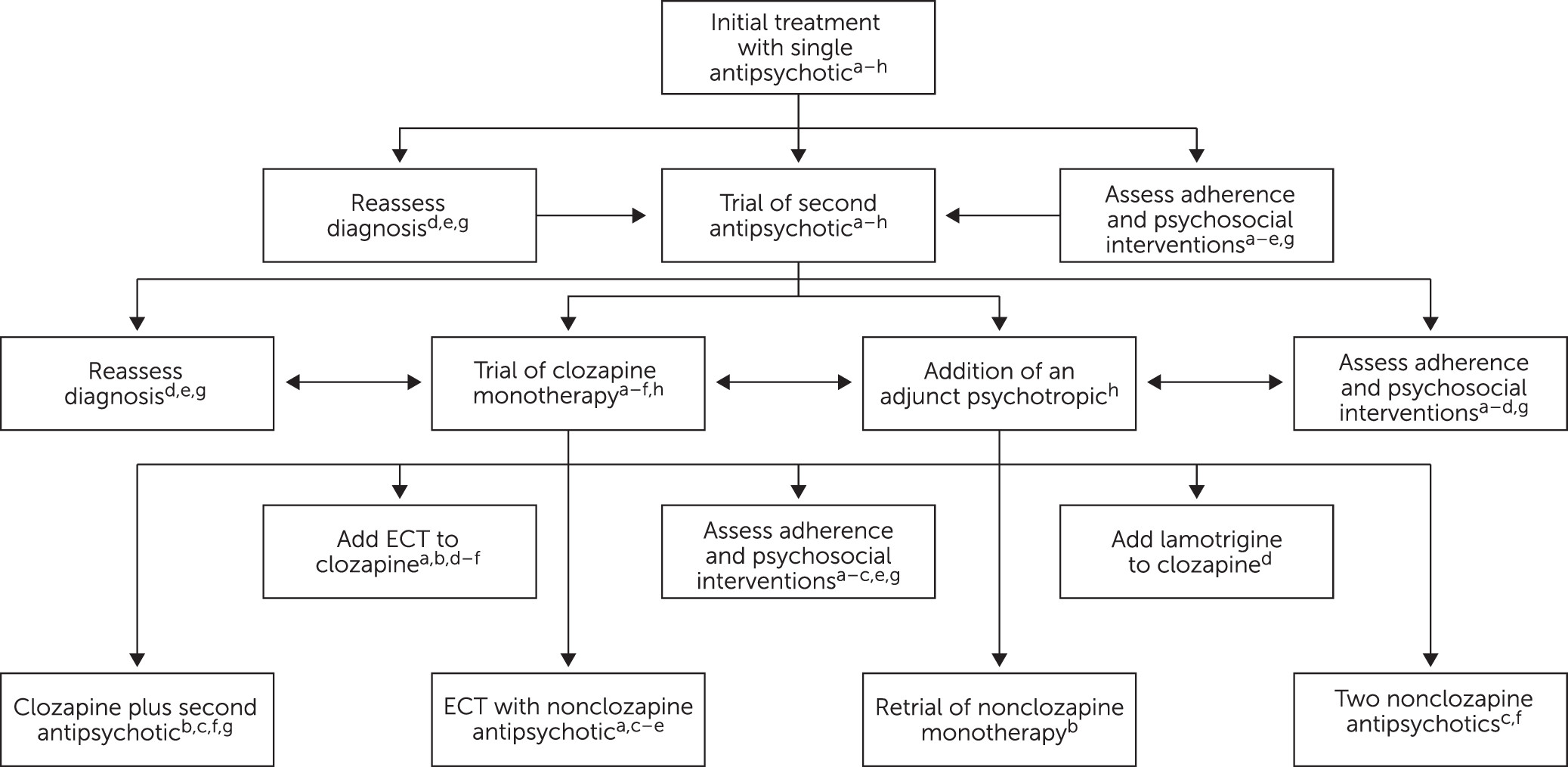

Patients in both case examples 1 and 2 would have been, according to existing guidelines, good candidates for clozapine. Among eligible patients, clozapine is infrequently prescribed (between 15% in the United States and 54% in the United Kingdom) despite guidelines recommending it after nonresponse to two other antipsychotics (see

Figure 1) (

30). Reluctance to use clozapine perpetuates the low frequency of clozapine prescriptions and thus prescribers’ and trainees’ limited exposure to patients who remit or recover on clozapine (

31). Moreover, the mandatory monitoring of white blood and absolute neutrophil counts compounds prescribers’ reluctance to initiate the drug. This reluctance is further increased by the presence of other potentially serious adverse effects: orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, syncope, seizure, myocarditis and cardiomyopathy, and increased mortality in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis. Recent evidence has also suggested that clozapine may cause increased mortality risk among patients with pneumonia (

32). Despite these concerns, the effectiveness of clozapine among patients with schizophrenia who are treatment resistant or who experience suicidal ideation remains superior (

33,

34). In their 2019 meta-analysis on clozapine and long-term mortality risk, Vermuelen et al. (

33) also found that continuous clozapine use has the lowest all-cause mortality risk of any antipsychotic.

Clozapine is a highly effective antipsychotic used for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. However, 40%−60% of patients who meet this criterion (

13) will have an incomplete response (

35) to clozapine monotherapy. Clozapine in combination with a second antipsychotic currently has the best, although limited, evidence in terms of antipsychotic polypharmacy. Clozapine is commonly used in combination with amisulpride, haloperidol, and sulpiride and is increasingly used with aripiprazole as the augmenting antipsychotic to maximize D

2 receptor blockade.

The combination of clozapine and risperidone is possibly the most well studied of the clozapine combination strategies. RCTs comparing clozapine and risperidone with clozapine monotherapy are equivocal (

35,

36). Some studies have indicated that combination therapy is more efficacious than clozapine monotherapy for positive and negative symptoms and disorganized thoughts, some have indicated that it is less effective, and some have shown no difference. These mixed findings may indicate that specific populations benefit from the combination therapy, but the criteria to identify those populations have not yet been found.

Sulpiride, amisulpride, and levosulpiride are atypical antipsychotics in the benzamide class that are not approved in the United States, Canada, or Australia but are used in other countries. Clozapine with sulpiride has been reported to improve positive and negative symptoms (

37). Sulpiride and risperidone have been found to be equally efficacious in combination with clozapine. In their 2017 review of clozapine combinations for the treatment of schizophrenia, Barber et al. (

37) found that amisulpride combined with clozapine is reported to be more efficacious than quetiapine combined with clozapine and noted improvement in the global assessment of function, clinical global impression, and depression, but not psychosis.

The combination of clozapine and aripiprazole shows promise as a way to ameliorate some of the side effects of clozapine. Jeon and Kim (

36), in their evaluation of the concerns with antipsychotic polypharmacy and metabolic syndrome (i.e., the state of hyperlipidemia, obesity, hypertension, and glucose intolerance), found two RCTs in which body weight and thus body mass index improved and cholesterol levels decreased, although psychosis did not improve. Jeon and Kim (

36) also found open-label trials in which patients showed improved metabolic markers and decreased somnolence. Aripiprazole and clozapine combinations have also been shown to have fewer side effects than clozapine and haloperidol combinations but are similarly efficacious (

37). Tiihonen et al. (

13) explored the association of antipsychotic polypharmacy versus monotherapy with risk of rehospitalization among persons with schizophrenia and found that the lowest risk was observed with the combination of clozapine and aripiprazole (7%−14% lower than any antipsychotic monotherapy). They also found that patients treated with clozapine and aripiprazole had a better outcome in terms of both psychiatric hospital readmission and all-cause hospitalization than those treated with any other monotherapy or combination of antipsychotics.

Case example 3: minimizing side effects of the initial antipsychotic drug while achieving response or remission.

A 23-year-old man with schizophrenia, cocaine use disorder, and medication nonadherence was admitted for crisis stabilization five times in 12 months for active psychosis, a suicide attempt by an overdose of ibuprofen, and threats to harm others. At the last admission, he was grossly psychotic and threatened to harm his case manager. The patient did not improve after one week of inpatient care on 30 mg/day olanzapine. The inpatient unit team applied for the patient’s transfer to long-term care, and it took two additional weeks for a bed to be secured for him. His new inpatient treatment team, after reviewing the records and history obtained from the patient and his family, proposed starting treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic, potentially olanzapine, because the patient had eventually showed improvement with an oral formulation. However, the patient adamantly refused to take a monthly injection, stating that he did not like needles. The patient also declined clozapine given the need for a weekly blood draw. After approximately four weeks of hospitalization, the patient became calmer and less paranoid, started attending groups, and frequently played basketball in the recreation area. However, he maintained active hallucinations with derogatory content that bothered him, particularly at night. The patient had a family history of diabetes and gained seven pounds on olanzapine. Given his partial response to high-dose olanzapine, recent weight gain, and family history, the psychiatrist recommended adding 5 mg/day aripiprazole, with the intent of addressing the remaining hallucinations and delusions and diminishing the metabolic side effects. After another two weeks of inpatient care, the patient stabilized on olanzapine (decreased to 20 mg/day) and 5 mg/day aripiprazole and was discharged in the care of an assertive community treatment (ACT) team. Subsequently, the patient attended Narcotics Anonymous and the local psychosocial clubhouse program. He played basketball with friend three times a week and lost five pounds. He inquired about scholarship opportunities at the local community college. Given the patient’s marked improvement, the ACT team psychiatrist and patient alike were reluctant to change the patient's medication, although it involved a combination of antipsychotics.

As reflected in this case example, if weight gain or metabolic disturbance is present but psychotic symptoms persist, clinicians may choose to add another antipsychotic with higher D

2 receptor affinity and address the persisting symptoms while lowering the dose of the antipsychotic with higher liability of metabolic syndrome. Long-term use of antipsychotics among patients with schizophrenia increases the risk for metabolic syndrome (

2,

38). The relationship between antipsychotic drug combinations and metabolic syndrome is complex and likely dependent on multifactorial issues such as multiple receptors, failed glucose homeostasis, and lifestyle factors. The mechanisms for the metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics are multiple. Coccurello and Moles (

39) found that antipsychotics with the greatest weight gain liability share a high affinity for serotonin (5-HT

2A, 5-HT

2C, 5-HT

6, and 5-HT

7), muscarinic (M

1, M

2, M

3, and M

5), histamine (H

1), adrenergic (alpha

1 and alpha

2 but also beta

3), and dopamine (D

1 and D

2-like) receptors. Ijaz et al. (

2) found insufficient data for the potential harm of antipsychotic polypharmacy, including metabolic syndrome, noting a potential protective effect of antipsychotic combinations that included aripiprazole for dyslipidemia and glucose metabolism compared with other combinations and monotherapy. The finding of a protective role of aripiprazole calls for further investigation. Data are emerging about the effectiveness of aripiprazole added to decrease the metabolic burden of clozapine (

34).

The treatment team in case example 3 also had the option to completely cross-titrate a second antipsychotic (in this case, aripiprazole). However, improvement and stabilization while cross-titrating two antipsychotic drugs may result in the patient being kept on both antipsychotics to prevent illness relapse, which could lead to long-term polypharmacy. Although each of the patients in the case examples presented could ideally benefit from taking only one antipsychotic, the clinical and practical considerations in each case make antipsychotic polypharmacy necessary to stabilize the patients and allow them to progress toward recovery.