People diagnosed as having bipolar disorder are at a substantially elevated risk of suicide death, estimated at 164 deaths per 100,000 per year, or 10 to 20 times above the general population risk (

1). Among those with bipolar disorder who enter into the mental health care system, 5%–8% will ultimately die by suicide (

2). With such increased risk, suicide risk assessment and intervention are invariably at the core of the assessment and management of patients with bipolar disorder. This article summarizes the available literature on correlates of suicide-related behavior among those with bipolar disorder and provides clinicians with an understanding of which specific elements of the clinical history may be most impactful when developing a person-specific risk evaluation. A special focus on youths is included to assist in the assessment process for this distinctive patient group.

This article takes a broad approach at suicide prevention strategies and summarizes not only what is known about diagnosis-specific interventions, but also the broader clinical and community-based literature. Particular emphasis is given to the emerging area of interventional psychiatry and to population-based strategies. As the evidence has become clearer that risk assessments are ultimately limited in their predictive value, the management for all patients with bipolar disorder should incorporate suicide prevention strategies irrespective of perceived risk or treatment setting. It should be noted that the information presented in this article does not establish a clear hierarchy or ranking of risk factors, nor is a patient-specific risk calculator for suicide available for general clinical use. The extant data should rather be used to inform a general understanding of correlates of suicide-related behaviors in patients diagnosed as having bipolar disorder.

Factors Correlated With Suicide Risk in Bipolar Disorder

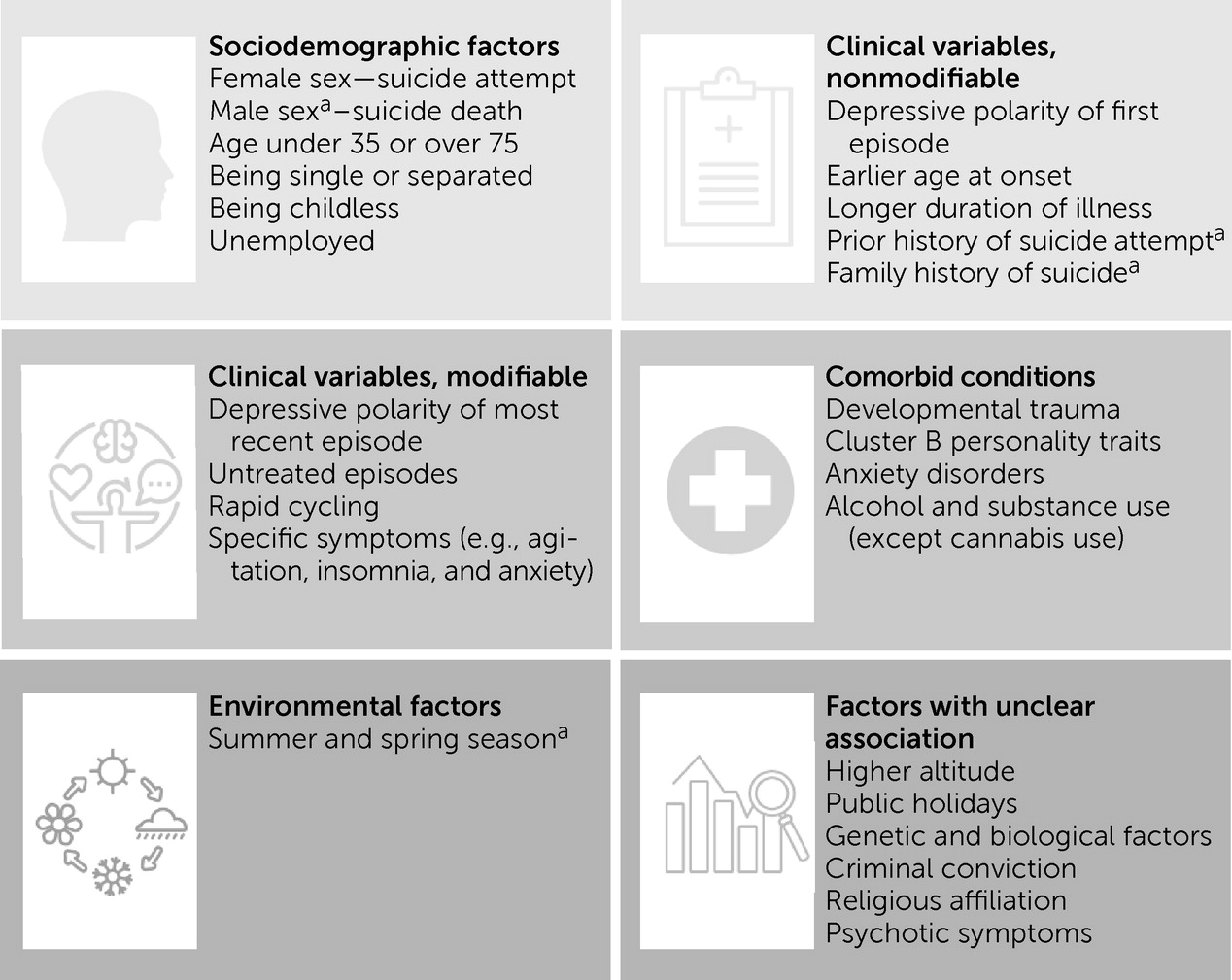

Despite the absence of a consensus set of predictors or risk models of suicide in the general bipolar disorder population, the extant literature provides key information on specific variables of importance (

Figure 1). Several sociodemographic factors have been linked to suicide attempt and/or death risk in bipolar disorder. Females with bipolar disorder have higher rates of suicide attempts (odds ratio [OR]=1.54) (

1), whereas males with bipolar disorder are twice as likely to die by suicide. However, the sex ratio is smaller than general population samples, which suggests that the impact of the illness on population-level risk is uneven, so that women with bipolar disorder are at higher relative risk. Some studies have shown a higher risk for suicide in patients with bipolar disorder who are younger (under age 35) or older (over age 75), single, separated or divorced, unemployed, or without children (

3–

5). There have been mixed results on the role of religion; some studies have shown that a religious affiliation is protective, whereas other studies have suggested that increased religious preoccupation in a subset of patients with bipolar disorder could lead to higher levels of distress and suicide-related behavior (

3).

Among course of illness and clinical variables, the strongest association has been found with depressive polarity of the most recent episode (OR=5.99). Furthermore, those with depressive polarity of the first episode are twice as likely to attempt suicide (

1). The time in which a person emerges from a hypomanic episode and experiences depression is often characterized by a highly contrasted shift from positive to negative cognitive appraisals and can be a specific moment of increased risk (

6). Overall, the stratification of absolute risk from highest to lowest between the episode types appears to be depressive, mixed, and manic/hypomanic (

7). Despite a higher relative risk of suicide attempts during mixed states compared with depressive episodes, the absolute risk of suicide attempt during depressive episodes remains higher due to patients spending substantially more time in depressive than mixed episodes. Additionally, some studies suggest that increased risk of suicide in mixed states is related to the overall increased length of depressive symptoms in this subgroup and can be statistically explained by the presence of depressive symptoms alone (

8). Longer duration of illness and untreated episodes, rapid cycling, and symptoms such as agitation, insomnia, and anxiety are correlated with elevated suicide risk (

9). There are inconsistent results regarding the association between psychotic symptoms and suicide-related behavior, with some studies identifying reduced organization and planning capacity in patients with bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms being associated with lower rates of suicide attempts (

10). Patients with early maladaptive schemas and developmental trauma appear to be at higher risk for suicide attempts and lifetime suicide risk (

11). Earlier age at onset is a strong correlate of suicide attempt risk, and the average age at onset is 3 years younger in patients with bipolar disorder with a history of suicide attempts (

1). It is unclear if this is related to a more severe illness associated with earlier onset, or because of more years spent with the illness resulting in a higher cumulative probability of suicide (

12).

In terms of subtypes of bipolar disorder, earlier studies suggested that bipolar II disorder had a higher risk for suicide attempt, owing to predominantly depressed and mixed states (

3); however, recent studies have shown mixed results. Some studies show a higher rate of suicide attempts in bipolar II disorder (

13), whereas recent meta-analyses suggest there is no difference in suicide attempts between bipolar I and II disorder (

1). Prior history of suicide attempts, recent admission, and upcoming discharge have additionally been associated with heightened suicide risk (

14). Finally, first-degree family history of death by suicide is strongly associated with suicide attempts and deaths and may predict earlier attempts (

1,

3).

In terms of comorbid conditions, the presence of a lifetime anxiety disorder is strongly associated with risk of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder. Although this has been observed as a lifetime association, it remains unclear if the onset of the anxiety disorder precedes the occurrence of the suicide attempt (

1). Alcohol and substance use disorders, with the exception of cannabis use disorder, have been shown to be significantly associated with risk of suicide attempt in bipolar disorder, with the highest risk shown for alcohol (

1,

4). Impulsivity may be the mediating factor between alcohol use and suicide attempts (

1). Cluster B personality disorders, and borderline personality disorder in particular, are strongly associated with risk of suicide attempt. There is currently insufficient data on other personality clusters (

1).

Most studies have focused on factors correlated with suicide attempts rather than suicide deaths in bipolar disorder. Overall, a prior suicide attempt increases risk of death by suicide 37-fold in bipolar disorder (

7). Suicide-related behavior in individuals diagnosed as having bipolar disorder tends to be more lethal than that observed in the general population, particularly among women (

12). There is seasonal variability in bipolar disorder suicide deaths, with more deaths occurring in spring and summer compared with fall and winter (

4). There is an absence of data linking lifetime substance use with increased risk of suicide deaths in bipolar disorder, but this should be interpreted with caution as data are limited and contrast with findings in depression and schizophrenia (

1). Additionally, psychosis has not been shown to have any significant association with suicide deaths (

1).

There are several other environmental and individual factors that remain under study for associations with suicide risk in bipolar disorder. Studies have reviewed higher altitude, genetic components, biological factors such as cortisol level, and other factors such as criminal conviction and public holidays as possible risk factors (

3,

4), but the results remain preliminary.

Suicide Risk in Youths With Bipolar Disorder

Youths with bipolar disorder are an important subgroup in which to understand suicide risk. The risk of death by suicide among youths with bipolar disorder is higher than any other psychiatric disorder in adolescence (

15,

16), including major depressive disorder (

17). Although the relative rarity of suicide in this age group makes it challenging to establish an accurate rate of suicide deaths, the available evidence suggests that the suicide rate among youths with bipolar disorder is in line with the well-established 10 to 30 times increased risk of suicide in adults with bipolar disorder (

18). A meta-analysis including data from 15 countries reported a pooled annual rate of suicide attempts of ∼7.5% among youths with bipolar disorder (

17). Similarly, the estimated prevalence of lifetime suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in youths with bipolar disorder range as high as 35%–46% (

16,

19–

21) and 14%–21% (

16,

19,

21), respectively.

Among the numerous demographic, clinical, and psychosocial risk factors associated with suicide-related behavior among youths with bipolar disorder, one of the most robust is female sex (

22). Similar to the adult population, the female-to-male suicide mortality ratio is narrower than for other psychiatric conditions or the general population (

23). Data from coroner cases of suicide show that individuals with bipolar disorder are more likely to be female and younger than those without bipolar disorder (

24). Given that the prevalence of bipolar disorder is higher among females compared with males in adolescence (

15,

25) but not at any other point in the lifespan, the elevated risk of suicide among adolescent females with bipolar disorder may necessitate targeted and sex-specific intervention.

Younger age at bipolar disorder illness onset is also a clinical risk factor for suicide, with several studies noting an association between earlier age at illness onset and increased suicide attempts (

16,

26). In terms of illness course among youths with bipolar disorder, mixed episodes (

16,

21), increased number of mood episodes (

27), and presence of depressive symptoms (

16,

21) are correlated with increased risk of a suicide attempt. Comorbid psychiatric conditions, specifically anxiety disorders (

19), posttraumatic stress disorder (

19), substance use disorders (

16,

19), and eating disorders (

19) further contribute to risk of suicide attempts in youths with bipolar disorder. Familial risk factors such as history of depression (

16,

19), suicide and/or suicide-related behavior (

16,

19), as well as poor family functioning (

21) are also linked to suicidal ideation (

20) and suicide attempts (

21) among youths with bipolar disorder. Other psychosocial risk factors include a history of sexual and/or physical abuse (

19). Data on correlates of suicide-related behaviors in youths with bipolar disorder have informed the creation of a risk calculator to more efficiently assess suicide attempt risk in this vulnerable population (

28). Although work in this area is preliminary, risk calculators may effectively complement traditional risk assessment measures and clinical judgment to identify youths with bipolar disorder who are at an elevated risk for suicide-related behavior.

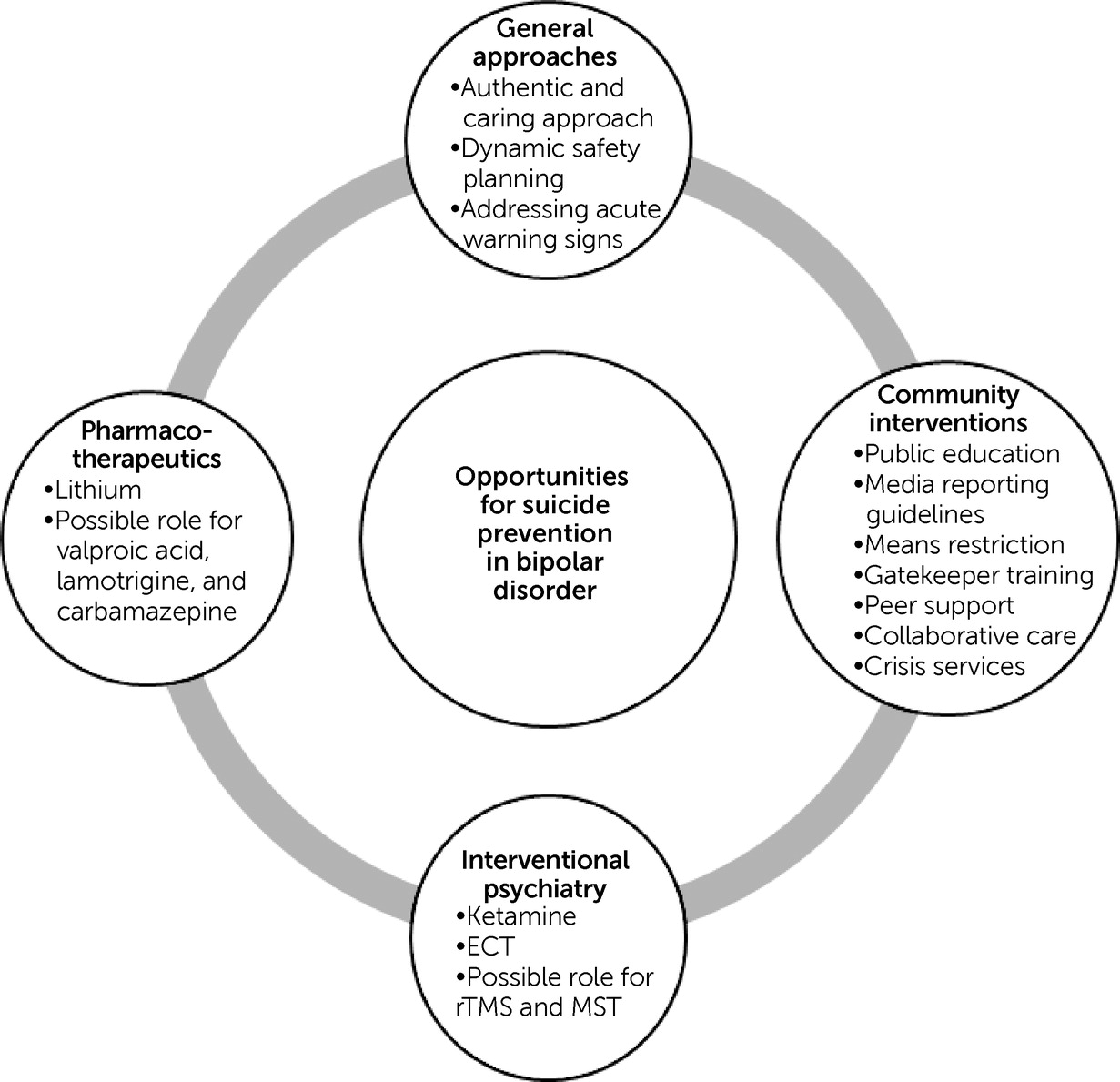

Pharmacotherapeutic and Other Biological Approaches

Multiple meta-analyses have shown that long-term treatment with lithium is strongly associated with a reduced risk of suicide in unipolar and bipolar depression, an effect that can be present even without achieving mood stabilization (

9,

30,

31). Furthermore, abrupt lithium discontinuation can increase suicide risk, which can be partially mitigated by a slow taper (

5). However, prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of lithium’s putative antisuicide effect in bipolar disorder have been underpowered, and thus top-level evidence on the question of a specific and unique antisuicide effect remains elusive. Treatment with anticonvulsants such as valproic acid, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine has also been associated with reduced suicide risk in some studies, albeit to a lesser degree, and this is not universally observed (

9,

31). A 2018 meta-analysis found no protective effect from valproic acid against suicide attempts and deaths in bipolar disorder. This could be attributed to less effective antidepressant effects from this agent in bipolar disorder (

32). Further studies are needed to clarify how the anticonvulsants compare with each other and if their effects are independent of mood stabilization (

9,

31). There has been no clear evidence for antisuicide effects with antipsychotics, and the effects shown for clozapine appear to be specific to schizophrenia (

9). There is mixed evidence for antidepressants, and they may increase risk in case of emergence of insomnia and agitation (except for the combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine) (

5). There is preliminary evidence suggesting that combination of chronotherapies (light therapy and sleep deprivation) with lithium can provide rapid reduction in suicidality in patients with bipolar depression; however, there is need for further studies and randomized trials to confirm this potential effect. Furthermore, there is no evidence identified with regard to the effect of other strategies such as use of melatonin or blue-blocking glasses on suicide-related outcomes in bipolar disorder (

33).

Interventions for Suicide Prevention in Youths

Early intervention for youths with bipolar disorder has the potential to dramatically affect the life trajectory of these patients. The literature on suicide prevention among youths with bipolar disorder is limited, when compared with adults with bipolar disorder and to youths with other psychiatric conditions; however, there are promising findings that warrant discussion and future investigation. The prevention of suicide among youths with bipolar disorder begins with the clinical interview of youths who present with major depression. “Red flags” such as early age and/or rapid symptom onset, psychomotor retardation, psychotic features, family history of bipolar disorder, and severe and/or refractory depressive symptoms have high specificity for predicting bipolar disorder (

45). Accurate and timely detection of subthreshold or threshold hypomanic or manic symptoms is another opportunity for early intervention and, hence, suicide prevention (

46).

Pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment among youths with bipolar disorder. There is some preliminary evidence for suicide risk reduction in adolescents with bipolar disorder who receive lithium (

47), and that lithium can also improve the overall long-term outcomes of bipolar disorder. Therefore, just as for adults, the relationship between suicide risk reduction and lithium among youths with bipolar disorder merits a more refined exploration. Psychotherapy, another principal component of treatment for bipolar disorder in youths, is also an intervention that has the potential for direct suicide prevention. Evidence-based treatments for bipolar disorder in youths, such as family-focused therapy, reduce depressive symptoms (

48), whereas interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (

49) helps lower depressive and manic symptoms, and improves overall functioning, thereby likely indirectly reducing the risk of suicide. Importantly, there is recent early evidence that dialectical behavior therapy tailored toward adolescents and families reduces suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adolescents with bipolar disorder (

50). In conclusion, future research that replicates and builds upon the promising findings to date, as well as resources targeted toward efficient and widespread implementation of these strategies, must be a priority in this field.