Cognition in Bipolar Disorder: An Update for Clinicians

Abstract

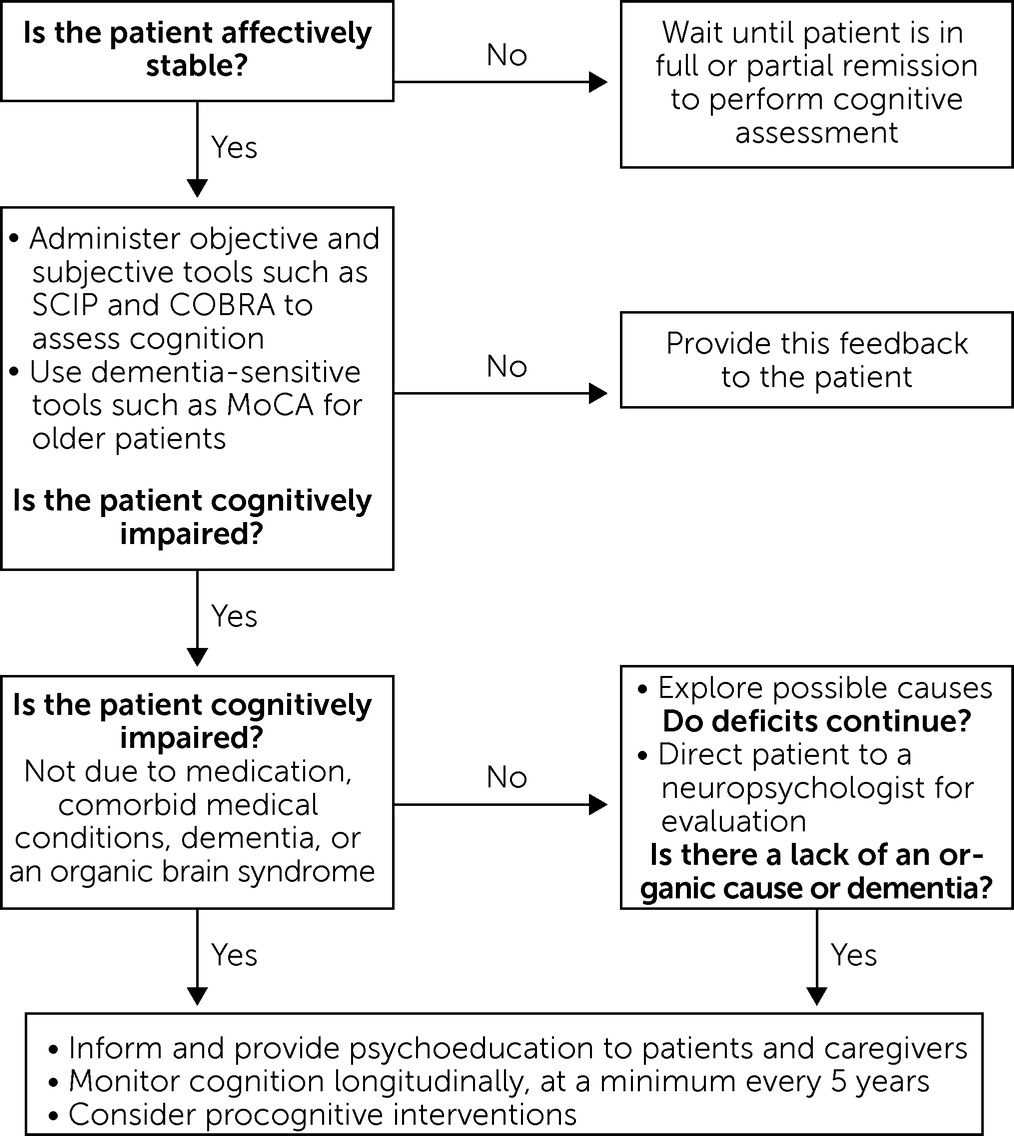

Measurement of Cognition in Bipolar Disorder

In the Clinic

Across the Lifespan

Importance of Brief Objective and Subjective Cognitive Screenings

Research

| Measure | Time to administer |

|---|---|

| Prescreening cognitive assessment for use in clinical trials | |

| MOCA (47) | 10 min |

| SCIP (35), objective measure | 15 min |

| Brief cognitive assessments for use in clinical settings | |

| SCIP (35), objective measure | 15 min |

| COBRA (36), subjective measure | 10 min |

| ISBD-BANC cognitive domain | |

| Speed of processing | |

| BACS: Symbol coding (42) | 3 min |

| Category fluency: animal naming (42) | 2 min |

| Trail Making Test–Part A (42) | 2 min |

| Attention/vigilance | |

| Continuous Performance Test–Identical Pairs (42) | 13 min |

| Working memory | |

| Wechsler Memory Scale–III Letter–Number Sequencing (42) | 6 min |

| Wechsler Memory Scale–III Spatial Span (42) | 5 min |

| Verbal learning | |

| California Verbal Learning Test (43) | 10 min |

| Visual learning | |

| Brief Visuospatial Memory Test–Revised (42) | 5 min |

| Executive functioning | |

| Stroop Test (44) | 5 min |

| Trail Making Test–Part B (45) | 2 min |

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Testb (46) | 20 min |

| Real-world functioning measures | |

| FAST (37) | 6 min |

| UCSD UPSA-B (48) | 15 min |

| VRFCAT (49) | 30 min |

Cognition as a Treatment Target in Bipolar Disorder

Methodological Recommendations for Clinical Trials Targeting Cognition

Future Directions

Measures of Affective Cognition

Neurobiologically Relevant Biomarkers

Neuroimaging.

Inflammation-based biomarkers.

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Keywords

Authors

Author Contributions

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing PsychiatryOnline@psych.org or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).