Postpartum psychosis is a rare but serious psychiatric emergency that can have devastating impacts on the mother, baby, and family. If not identified and treated, individuals diagnosed as having postpartum psychosis are at an elevated risk for suicide and infanticide. Early identification and treatment of this condition is key to minimizing these risks and preventing negative consequences for the mother and baby.

Postpartum psychosis is not a separate diagnosis in

DSM-5 but rather exists as a specifier (

1). Studies of this condition vary as to whether it is considered a separate disorder or a variant of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. In this review, we define postpartum psychosis as a single or recurrent episode of mood and psychotic symptoms that is limited to the postpartum period (the time between birth and 1 year postpartum). The clinical presentation of postpartum psychosis can vary and can include symptoms of mood disorder, psychosis, and/or delirium. The etiology of this condition is not well understood, but there are multiple hypotheses that we will briefly describe in this paper. We will also summarize clinical features, treatment, and prevention. We include literature that focuses on postpartum psychosis. We used search terms such as postpartum psychosis, postpartum bipolar disorder, and corresponding terms for clinical presentation, epidemiology, assessment, and treatment, and the search engines PubMed and Google Scholar (

2). We limited our search to articles published in English, beginning with the year 1994 (which was when

DSM-IV with the postpartum specifier for psychosis was published). We included review articles, and articles that had clinical relevance to a psychiatric practitioner. After this selection, the years of publication of selected articles ranged from 2003 to 2023. For each of the articles reviewed, we extracted information on prevalence, risk factors, clinical presentation, outcomes, prevention, and interventions for postpartum psychosis.

Prevalence

The most frequently reported incidence of postpartum psychosis is 0.89 to 2.6 in 1,000 births (

3). Variations in definition, timeline, and assessments used to diagnose postpartum psychosis may lead to the wide range of reported prevalence. All studies concur that the rate of postpartum psychosis is higher in women who have a history of postpartum psychosis (

4).

Etiology

Although childbirth is the trigger for postpartum psychosis, the etiology of this condition is unclear, and many questions remain unanswered. Genetic factors, immune and neuroinflammatory mechanisms, and hormonal changes such as rapidly declining estrogen postpartum, as well as circadian rhythm disruption and sleep deprivation are implicated in the development of postpartum psychosis (

5,

6). Although no hormonal abnormalities have been demonstrated in women diagnosed as having postpartum psychosis, some investigators hypothesize that a subgroup of women are more vulnerable to hormonal changes that occur after delivery. There is also recent research that explores the role of the immune system and potential mechanisms that underly the association of immune system dysregulation and postpartum psychosis (e.g., disturbances in the Treg–CCN3 protein–(re)myelination axis) (

7). Although genetic factors are suspected as playing a role in the pathophysiology of postpartum psychosis, specific genes that contribute to increased risk of postpartum psychosis have not been identified. There are only a few studies that have explored brain function in women who experience postpartum psychosis. Those results demonstrated that women who are at risk for postpartum psychosis exhibited changes in the areas of the brain that are implicated in executive functioning, functional differences in tests of working memory and emotional recognition, and increased connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and other areas of the brain (

8).

Assessment

The symptoms of postpartum psychosis can have a sudden onset and can worsen rapidly, occurring commonly within the first 2 weeks after childbirth. However, women are at risk for developing symptoms for several months after birth. A broad range of symptoms can occur in individuals who experience postpartum psychosis, including symptoms of mania, depression, cognitive impairment, and psychotic symptoms such as paranoia, delusions, and hallucinations. In the largest cohort study of the phenotype of postpartum psychosis, 130 women were found to have three symptom profiles: manic (34%), depressive (41%), and atypical (delirium-like) (25%) (

9).

The diagnosis of postpartum psychosis may be missed because psychotic symptoms wax and wane and women may not report their symptoms to their families and providers. The earliest signs are restlessness, irritability, mood fluctuation, and insomnia (

4). Delusional beliefs are common and often center on the infant. Auditory hallucinations that command the mother to harm herself or her infant may also occur. Individuals who are diagnosed as having postpartum psychosis experience visual hallucinations more frequently than those who have primary mood or psychotic disorders. Most women have dysphoric mania or mixed affective states, with symptoms of both mania and depression co-existing or rapidly shifting. The most distinctive clinical feature of postpartum psychosis is its delirium-like appearance, with cognitive symptoms such as confusion, disorientation, derealization, and depersonalization (

9). Postpartum psychosis differs from postpartum depression because women diagnosed as having postpartum psychosis will not realize they are ill, are disconnected from reality, and experience delusions and hallucinations.

Assessing and understanding a patient’s experience is crucial to plan appropriate interventions that can have a significant impact on the patient. A review that explored the experiences of patients and the factors involved in their recovery (

10) revealed that recovery from postpartum psychosis can be a lengthy and nonlinear process that continues beyond the resolution of acute symptoms and can be influenced by the wider social context. Patient perceptions, including stigma and fear of losing the baby, can lead to delay in seeking care, family’s distress, and hopelessness. This emphasizes the fact that it is important to include patient, provider, and family education about postpartum psychosis early in the process of assessment.

Postpartum psychosis comes with an elevated risk of infanticide (4%) and suicide (5%). It has been reported that perinatal suicides more frequently use violent methods such as hanging, jumping, or self-incineration, compared with nonperinatal suicides (

1). In many cases, mental illness is not a feature of infanticide. For example, infanticide due to fatal maltreatment, the child being unwanted, or partner revenge are less likely to be related to mental illness. Altruistic or acutely psychotic motives are associated with infanticide in postpartum psychosis (

11).

When a patient presents as having suspected postpartum psychosis, a thorough medical history, physical and neurological examination, and laboratory studies must be performed to exclude other medical conditions that have similar clinical presentation. Laboratory studies should include, at a minimum, a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood cell count, thyroid-stimulating hormone with free T4 and thyroid peroxidase antibody, ammonia level, urinalysis, vitamin levels (thiamine, folate, B12), and urine toxicology (

12). Blood cultures should be considered in the presence of fever. If focal neurologic deficits are present on examination or the patient has had a seizure, consider brain imaging and lumbar puncture with autoimmune encephalitis panel (

13).

Differential Diagnosis

It is critical to differentiate postpartum psychosis from other conditions presenting similarly in the postpartum period. Common differential diagnoses are listed below.

Medical causes of psychosis in the postpartum period include infectious etiologies such as mastitis and endometritis, HIV and syphilis; electrolyte abnormalities; endocrinopathies such as postpartum thyroiditis, hypoparathyroidism, and Sheehan syndrome leading to hypothyroidism or cortisol deficiency; vitamin deficiency such as thiamine, B12, or folate deficiency; postpartum eclampsia, which can lead to seizures and stroke; autoimmune encephalitis; and substance use disorders such as stimulant use, opiate use, or cannabis use disorders. Rarely, a late onset metabolic disorder, such as urea cycle disorder and type I citrullinemia, can present in the postpartum period and is misdiagnosed as postpartum psychosis (

13,

14).

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

The perinatal period is a period of high risk for the onset and exacerbation of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); this risk is most apparent for women giving birth to their first child. A meta-analysis (

15) indicated that 2.07% of pregnant women and 2.43% of women in the postpartum period are diagnosed as having OCD. According to a longitudinal study that followed women from the third trimester of pregnancy through 9 months postpartum, the incidence of new OCD cases was estimated to be 4.7 new cases per 1,000 women each week during the postpartum period. By 6 months postpartum, the cumulative incidence of new cases of OCD was 9.0%, and most cases emerged during the first 10 weeks postpartum (

16).

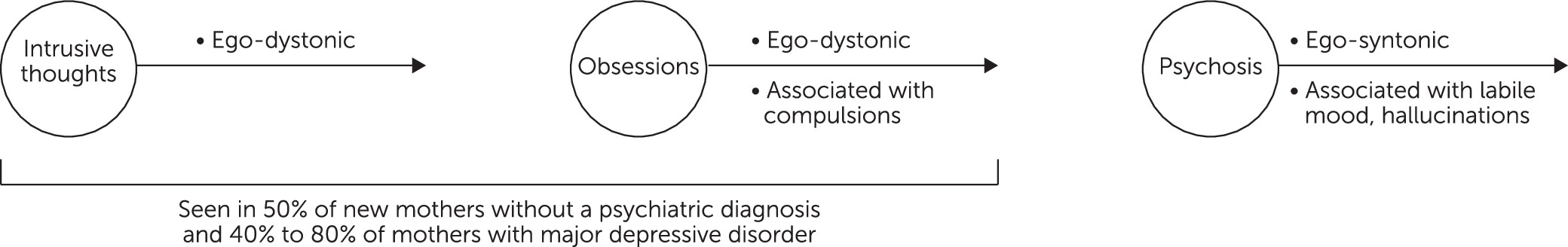

It is crucial to differentiate unwanted, ego-dystonic intrusive thoughts of harming the infant that are a symptom of postpartum OCD from ego-syntonic thoughts of harm secondary to postpartum psychosis (see

Figure 1). In postpartum psychosis, these thoughts of harm are often associated with hallucinations and delusions that are not seen in postpartum OCD, and are associated with a 4% risk of infanticide when mothers diagnosed as having postpartum psychosis act on their hallucinations and delusions (

17,

18). Whereas a person diagnosed as having postpartum psychosis believes the hallucinations and delusions are true, in postpartum OCD, the thoughts and ideas are inconsistent with their general sense of morality and their insight is preserved (

19). They are likely to experience high levels of distress, guilt, depressed mood, and a tendency to conceal the content of obsessions. Although mothers diagnosed as having OCD may fear harming their baby, there is no intent to harm, and studies have found no evidence of increased risk of infant harm among patients who experience postpartum OCD (

20). These thoughts horrify them, and they will protect and even avoid their infant. For example, in postpartum OCD the compulsions may not manifest as an active ritual but may occur as avoidance of the feared situation or objects that are associated with intrusive thoughts of harming the infant (avoidance of bathing the baby, removal of knives or the microwave from the kitchen).

Bipolar Disorder

Controversy surrounds the nosological relationship between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder. Clinical and epidemiological studies support the inclusion of postpartum psychosis within the bipolar disorder spectrum, but 25%–30% of women who are diagnosed as having postpartum psychosis never have affective episodes outside the postpartum period. Additionally, women who experience first-onset postpartum psychosis have a better prognosis and long-term outcome than women who are diagnosed as having bipolar disorder. Subsequent conversion to bipolar disorder among women who have postpartum onset of symptoms has also been studied (

21). Fourteen percent of women who have first-time psychiatric contacts during the first postpartum month converted to bipolar disorder within a 15-year follow up compared with 4% of women who have a first psychiatric contact that is not related to childbirth.

A case control study (

22) found that first-onset postpartum psychosis has a distinctive genetic risk profile, which only partially overlaps with that of bipolar disorder. First-onset postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder overlap when considering genetic vulnerability to bipolar disorder and schizophrenia; however, women with first-onset postpartum psychosis have a significantly lower genetic vulnerability to major depression (similar to controls) than women diagnosed as having bipolar disorder.

Women who have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder have a 20% chance of experiencing postpartum psychosis and a 25% chance of experiencing postpartum depression—an overall 45% chance of postpartum episode. Postpartum episodes among women who are diagnosed as having bipolar disorder have some unique risk factors and clinical features. For example, those who report a history of sleep loss that triggers mania are more likely to experience postpartum psychosis (

23), and mixed features with perplexity occur more frequently during postpartum manic episodes as compared with manic episodes at other periods in life (

24).

Women who are diagnosed as having bipolar disorder who have a postpartum onset depressive episode may have a more favorable longitudinal course than women who have onset of bipolar disorder at other times of life (

24), such as fewer suicide attempts and fewer lifetime depressive episodes (

25). Recommendations for bipolar disorder screening vary (

26). The Maternal Mental Health: Perinatal Depression and Anxiety Patient Safety Bundle recommends screening for bipolar disorder with the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) or the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Based Bipolar Disorder Screening Scale before prescribing antidepressants (

27). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Perinatal Mental Health Tool Kit (

28) recommends considering screening all women for bipolar disorder and using the MDQ only once in the perinatal period as it queries lifetime experience.

Major Depression With Psychosis

Major depression with psychotic symptoms in the postpartum period has been inadequately studied. However, a small longitudinal study that used structured clinical interviews of primiparous women who have a history of major depressive disorder found that 23% had psychotic symptoms at one or more time points (

33). Patients who experience an episode of unipolar major depression may have low mood, may be concerned that they are unable to enjoy their baby, may have psychomotor retardation or agitation, and may have other symptoms such as anxiety and poor concentration (

12). Unlike in postpartum psychosis, symptoms do not typically fluctuate. A cross-continental collaboration found that both diagnosis and treatment of postpartum major depression with psychosis varied across three geographical sites, with lithium, second-generation antipsychotics, antidepressants, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) being used to different extents (

34). Either the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 or the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale can be used to screen for major depression (

35,

36) and are usually paired with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale, given the high rates of co-occurring depression and anxiety. Recommendations are to screen for depression and anxiety at the initial prenatal visit, later in pregnancy, and at postpartum visits (

28).

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia in the perinatal period, like major depressive disorder with psychotic features, has been inadequately studied. Diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia include symptoms persisting for at least 6 months (

37). Symptoms during pregnancy and the postpartum period reflect symptoms of the pre-existing illness, including negative symptoms, delusions, and hallucinations. The peak age at onset of schizophrenia is 26–32 years, which is also commonly the childbearing age. Some studies indicate that pregnancy and childbirth are not associated with an increased risk of schizophrenia; others indicate that childbirth can cause psychotic symptoms to relapse. Women who are diagnosed as having schizophrenia represent 4%–18% of cases of postpartum psychosis (

29).

Management

Level of Care

Postpartum psychosis is considered a psychiatric emergency due to the rapid development and deterioration of symptoms and elevated risk of suicide and infanticide. When patients develop symptoms, it is important to determine the right level of care. Postpartum psychosis usually requires psychiatric hospitalization. Ideally, mothers are admitted to inpatient psychiatric units that allow for the baby to remain with the mother. These units, termed Mother and Baby Units (MBUs) are common in U.K., Australia, and India. They are designed to focus on safety, support, and education. In the U.S., in the absence of MBUs, perinatal psychiatry inpatient units have emerged (

38) that allow extended visitation with the baby. In the absence of MBUs or perinatal psychiatry units, babies are separated from the mother for the duration of inpatient hospitalization, which increases the risk of interrupted bonding. At the time of discharge after psychiatric hospitalization, patients diagnosed as having postpartum psychosis require a customized management plan to ensure the safety of the mother and the baby. The Cornell Peripartum Psychosis Management Tool (

39) offers a template for comprehensive peripartum management and discharge planning.

Nonpharmacological Treatment

It is important to identify women who are at risk for postpartum psychosis, and provide preconception counseling, regular psychiatric care, close monitoring, and prompt treatment for symptoms (

40). Psychoeducation of the partner and family is important as it can help them understand the illness, know what to look for, and provide support to the women who are experiencing postpartum psychosis. The broader goal for treatment extends beyond the improvement of clinical symptoms and includes attention to self-esteem, confidence in mothering, family and social functioning, and infant emotional and physical development (

14). Psychological support from providers, family, and psychotherapy are all essential parts of the treatment plan that can help address this broader goal.

Pharmacological Treatment

The choice of medication for postpartum psychosis depends on the clinical presentation, past trials, and side-effect profile. Second-generation antipsychotics and lithium are commonly recommended for postpartum psychosis (

40).

In the largest postpartum psychosis treatment trial to date (

13), a three-step treatment algorithm was followed. Step 1 involved the use of benzodiazepine at bedtime to treat insomnia as it is a common initial symptom. Lorazepam is the preferred benzodiazepine given the short half-life, low levels in breast milk, and evidence that indicates little to no adverse effects in breast-fed infants. Infants should be monitored for sedation, poor feeding, and poor weight gain (

41). If a patient had psychotic symptoms, then antipsychotics were started in the first step. Step 2 was the addition of antipsychotics and step 3 was the addition of lithium. Women enrolled in this trial were followed 9 months postpartum and showed high rates of remission.

Although haloperidol was used as an antipsychotic in this trial, recent reviews recommend second-generation antipsychotics. There is no consensus on the first-line antipsychotic, but olanzapine and quetiapine are second-generation antipsychotics that are used frequently in the treatment of postpartum psychosis due to more available data on their safety in lactation, as noted in

Table 2.

Lithium has the most evidence for prophylaxis of postpartum psychosis. For patients who had a prior episode of postpartum psychosis, lithium can be started either immediately after birth or later in pregnancy. Recent studies show that lithium use during breastfeeding is not contraindicated, but close monitoring of levels in mother-infant pairs is recommended. If lithium is started postpartum, then monitoring of levels in the mother and infant is recommended on the 10th day after starting lithium. Infants should be monitored for feeding problems, dehydration, hypotonia, and lethargy, and infant bloodwork should include thyroid and renal function tests (

4,

42).

Electroconvulsive Therapy

ECT is effective for rapid clinical improvement in mania, severe depression, catatonia, and psychotic disorder, and for treatment resistance of these conditions outside of the postpartum time period (

43). Data regarding the use of ECT in the postpartum period are limited to case series and population studies that have limited sample sizes due to the low prevalence of postpartum psychosis. Retrospective studies of women who are treated for postpartum psychosis or postpartum affective disorders demonstrate excellent response and remission rates (

44,

45). ECT has also been used as a first-line treatment (

46). A Swedish population study suggested that the response rate to ECT for depression and psychosis is higher in the postpartum period than outside the postpartum period, with remission rates of 87% (in the postpartum group) compared with 73.5% (in the matched nonpostpartum group) (

47).

Indications for ECT include psychopharmacologic resistance, comorbid catatonia symptoms, need for rapid symptom remission such as low intake leading to compromised nutrition and hydration, and severe suicidality (

13,

14,

46). Other considerations for ECT include patient preference and desire to breastfeed, which can be limited by psychotropic medications (

13).

ECT is effective, and safe for both the patient and for the breastfeeding infant. The most common adverse effects in the postpartum period include cognitive symptoms, transient myalgia, and prolonged seizures during the ECT procedure (

45,

46). Mild, transient anterograde amnesia is the most common cognitive side effect and resolves days to weeks after the course of ECT is completed. However, despite their transient nature, cognitive symptoms can impair the patient’s ability to care for the infant fully and could impair mother-infant bonding, although postpartum psychosis likewise causes impairment in these domains (

45).

Despite being a safe and rapidly effective treatment for postpartum psychosis, access to ECT can be limited by lack of ECT providers, lack of knowledge of when to refer, stigma associated with ECT, and local statutes regarding consenting to ECT if the patient cannot provide informed consent (

43). See

Table 3 for a summary.

Prevention of Postpartum Psychosis

As a condition with a specific trigger, i.e., childbirth, and a time-bound period of elevated risk for relapse, i.e., the postpartum period, it should be possible to prevent many cases of postpartum psychosis. Attention to prevention is critically important given that postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency and is associated with high risk of infanticide and suicide. Early identification and treatment can hasten recovery and prevent prolonged disruption of the mother-baby dyad. We provide the following guidance for preventive interventions:

•

Identification of risk factors: Prevention begins with identification of well-established risk factors. There is a wide array of risk factors for postpartum psychosis, such as primiparity, young age, history of bipolar disorder, family history of psychosis or bipolar disorder, and sleep loss (

48). The strongest risk factor for postpartum psychosis is a history of postpartum psychosis after a previous pregnancy (

6). Stressful life events or perceived stress during pregnancy do not correlate with an increased risk for postpartum psychosis.

•

Pharmacological management: For individuals who have had a prior mood or psychotic episode, psychopharmacology is the mainstay of prevention. The approach depends on the primary diagnosis. The treatment plan is managed, ideally, in specialty mental health care or, at minimum, with psychiatric consultation. General guidance is to continue mood stabilizer medication through pregnancy for those who are diagnosed as having bipolar disorder. This guidance follows from studies that showed that in women having a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, postpartum relapse rates were significantly higher among those who did not use prophylactic medication during pregnancy (66%, 95% confidence interval [CI]=57–75) compared with those who did (23%, 95% CI=14–37) (

49). Among mood stabilizers, lithium has the strongest evidence of efficacy in preventing mood episodes and psychosis when started in pregnancy or postpartum (

50). Evidence regarding the use of second-generation antipsychotics is equivocal and valproate is not recommended for use in pregnancy given its high teratogenic potential and negative effects on neurodevelopmental outcomes. All decisions must be individualized and made after a thorough discussion of the risks of prophylactic medication during pregnancy against the risks of medication.

For those who experience episodes of psychosis that are limited to the postpartum period, prophylaxis using either lithium or antipsychotics immediately postpartum is effective in preventing postpartum relapse (

51). A recent review of interventions for the prevention of postpartum psychosis found 10 studies with sample sizes ranging from 1 to 29 that provide the most evidence for the prophylactic benefit of lithium, preliminary evidence for effectiveness of olanzapine, and mixed or equivocal findings for the effectiveness of oral and transdermal estrogen (

52).

•

Care coordination: It is essential for psychiatrists to coordinate with the patient’s entire care team. Coordination with obstetric clinicians will help to create a birth plan that includes the patient’s preference for mode of delivery, and guidance for rest and sleep immediately after delivery. The birth plan should also include the patient’s preference for feeding the baby and a recommendation to always prioritize sleep over breastfeeding. The baby’s pediatrician should be informed about any medications the mother is taking so that a plan can be made to monitor the baby for any effects of in utero exposure to medication.

•

Sleep: Insomnia is often the earliest and most common symptom of postpartum psychosis (

53), and interventions to enhance or protect sleep in the postpartum period are increasingly seen as essential in the prevention of postpartum psychiatric conditions. Psychiatrists should advise all mothers, and particularly those at high risk for postpartum psychosis, to consolidate their sleep for longer consecutive hours of sleep by leaning on social supports to help care for the baby at night (

54).

In the immediate postpartum period, stimulus reduction, including restricting the number of visitors, should be considered. Some recommendations include guidance on prescribing benzodiazepines or a sedating antipsychotic in addition to a mood stabilizer (

40). Compared with a matched control group, women who developed postpartum psychosis experienced a longer duration of labor and were more likely to have a nighttime delivery (

55). This implies that the sustained sleep loss associated with labor may have contributed to the risk of postpartum psychosis and, where feasible (e.g., with planned inductions and cesarian sections), a plan for daytime delivery should be made for women who are at high risk of postpartum psychosis.

•

Dyadic support: Prevention of the rupture of mother-infant bonding is a vital component of prevention in postpartum psychosis, and MBUs or perinatal psychiatry units (see above) play an important role in supporting dyadic care. Following discharge, attempts must be made to repair any rupture in attachment and provide parenting support as indicated (

56).

Early detection is a key component of prevention of negative outcomes. Psychiatrists must ensure a thorough assessment of individuals who present with mood or anxiety symptoms in the postpartum period to rule out the presence of psychosis or cognitive impairment.

Future research should include prospective studies of the effectiveness of various preventive interventions, and that consider different risk factors such as psychiatric and family history, symptoms during pregnancy, and obstetric complications. Ideally, such research will enable psychiatrists to customize prevention and treatment plans for patients on the basis of their individual risk factors.

Conclusions

Postpartum psychosis is a rare, but true psychiatric emergency, which, if left untreated, carries high risks for both the mother and the child and can have tragic consequences such as infanticide and suicide. However, with well-established risk factors, and effective preventive and treatment interventions, it is possible to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with this condition. Overall, postpartum psychosis has a good long-term prognosis, and as a psychiatric disorder with a specific and predictable time of onset, it is possible to prevent or treat early. There is a need to educate health care providers and patients and their families about the risk factors and clinical symptoms and emphasize the importance of seeking help early. Although patients with postpartum psychosis need specialty mental health care, prenatal, primary care, and pediatric providers can play a critically important role in early identification and in expediting connection to appropriate care.