Introduction

The menopause transition involves dramatic changes in levels of reproductive hormones and functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. During this time, women frequently report struggles with aspects of cognition, including learning, memory, and executive functioning. E

xecutive functioning domains of cognition include initiating and sustaining focus on tasks, temporarily retaining and utilizing information (working memory), processing speed, and motivation for work [

1–

4]. These executive functioning cognitive domains are especially relevant to the menopause transition because they are highly dependent on the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the neural structure and function of which is modulated by ovarian hormones such as estradiol [

5–

7]. However, the majority of research into the effects of the menopause transition on cognition have focused on domains of learning and memory, as opposed to exclusively examining executive functioning.

On learning and memory tasks, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women show poorer performance compared to premenopausal women, independent of age [

1,

8–

10]. However, the findings in this literature are inconsistent as to whether these cognitive difficulties persist past perimenopause or if they resolve in postmenopause. One longitudinal study found that cognitive difficulties peak during perimenopause and recover in postmenopause to premenopausal levels [

8]. Other longitudinal studies found that the perimenopausal decline in cognitive function does not recover or only partially recovers in postmenopause compared to premenopausal levels [

1,

11]. With the negative impact that cognitive difficulties have on quality of life, it is critical to determine what factors contribute to these symptoms during the menopause transition and what domains are most affected. The present study investigates how confounders, such as the type of postmenopause (natural vs. surgical) and current psychological symptoms, impact domains of executive functioning in different stages of menopause.

Natural and surgical postmenopause are distinct experiences with differing effects on cognitive function. Surgical postmenopausal women show more cognitive impairments compared to natural postmenopausal women, independent of age [

12–

14]. Several differences between natural and surgical postmenopause provide rationale for why cognitive dysfunction is relatively more pronounced following surgical postmenopause. First, the most common indication for surgical menopause (bilateral oophorectomy) is as part of gynecological or breast cancer care or risk reduction, necessitating procedures that induce an abrupt and permanent cessation of ovarian hormone production compared to the natural menopause transition [

15]. Second, surgical menopause often occurs before women have entered perimenopause, resulting in an earlier age at postmenopause [

16], and earlier postmenopause age is associated with poorer performance on verbal fluency and visual memory tasks [

17]. Third, women who undergo surgical menopause as part of cancer care may experience cognitive impairments related to having cancer and/or undergoing chemotherapy [

18,

19]. Thus, postmenopause type (natural vs. surgical) is important to consider when studying cognition across menopause stages. However, studies about cognition and the menopause transition often exclude participants with surgical postmenopause, group natural and surgical postmenopause together, or include relatively small sample sizes of surgical postmenopausal women [

8,

11,

20].

Psychological symptoms (e.g., disrupted sleep, increased anxiety and depression) also confound the relationship between cognition and menopause stage/type, as these symptoms commonly occur across the menopause transition [

21,

22] and negatively impact cognitive functioning [

23,

24]. More specifically, disrupted sleep, anxiety, and depression also negatively impact PFC-dependent executive functions [

25–

27]. However, studies control for these psychological variables inconsistently, which may help explain the observed variability among findings as to whether cognitive problems persist into postmenopause. Furthermore, the prevalence of symptoms that negatively impact cognition, such as depression and anxiety, is higher in women who underwent surgical menopause compared to age-matched women who did not have a bilateral oophorectomy [

28]. Despite this evidence, at present, no previous studies have investigated executive functioning and the menopause transition while accounting for possible confounding effects of both postmenopause type and psychological symptoms.

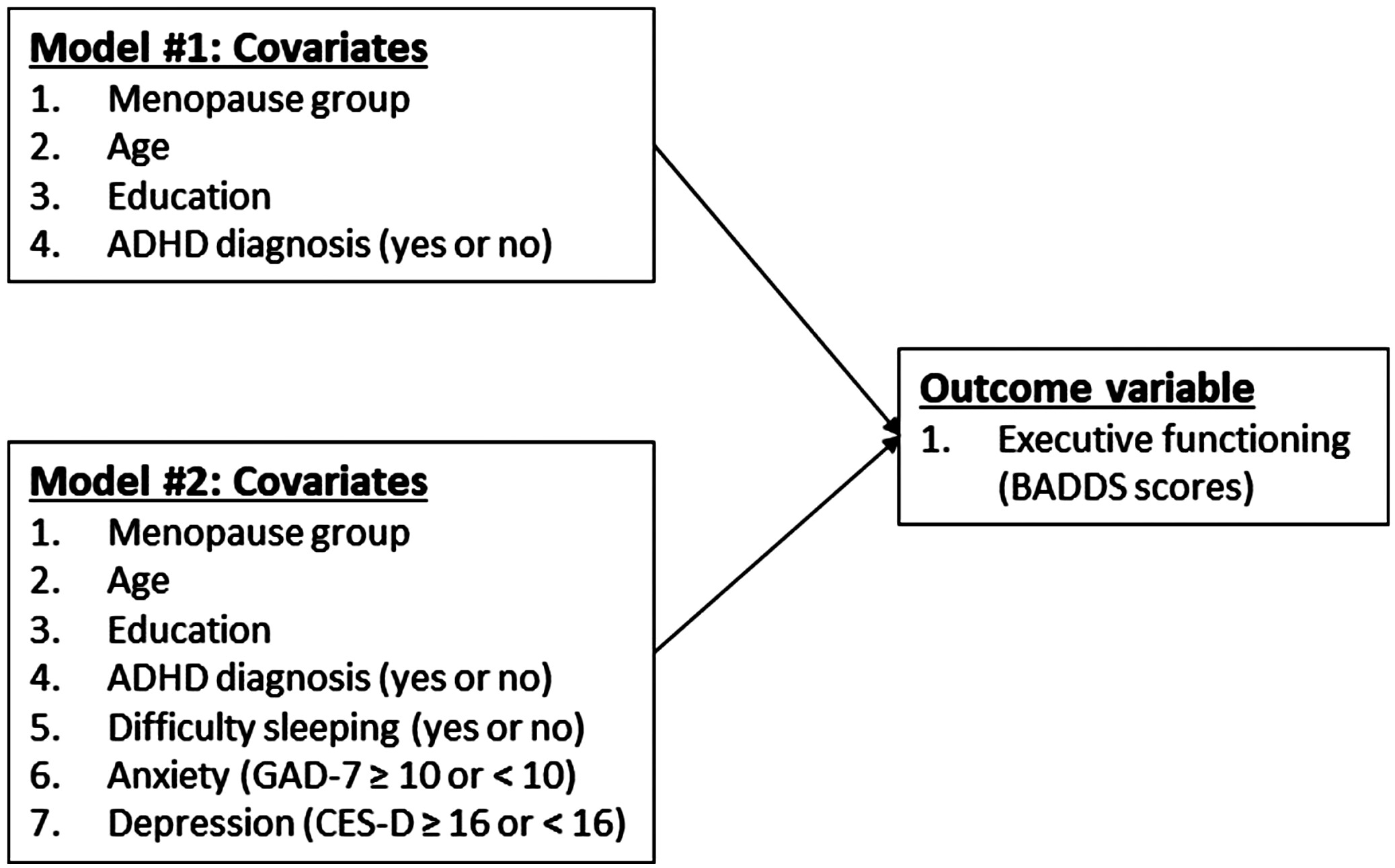

The purpose of this research is to investigate within the same study whether postmenopause type (natural or surgical) and current psychological symptoms (difficulty sleeping, anxiety, and depression) account for the persistence or recovery of cognitive difficulties, specifically executive functioning domains, in postmenopause. We utilized the Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Scale (BADDS) [

29] to assess executive functioning in premenopausal, perimenopausal, and natural and surgical postmenopausal women. The BADDS is a validated self-report measure of symptoms of attention hyperactivity deficit disorder (ADHD) that captures multiple domains of executive functioning [

30]. The BADDS has previously been used to assess executive dysfunction during the menopause transition and the effectiveness of pharmaceutical treatments aimed at improving executive function [

2,

24,

31,

32]. We analyzed the effect of menopause stage and type (premenopause, perimenopause, and natural and surgical postmenopause) on BADDS scores, with and without controlling for possible confounding variables, to better understand the relationship between the menopause transition and self-reported cognitive complaints and why discrepancies in the literature exist about the persistence of these cognitive difficulties, including executive dysfunction.

Discussion

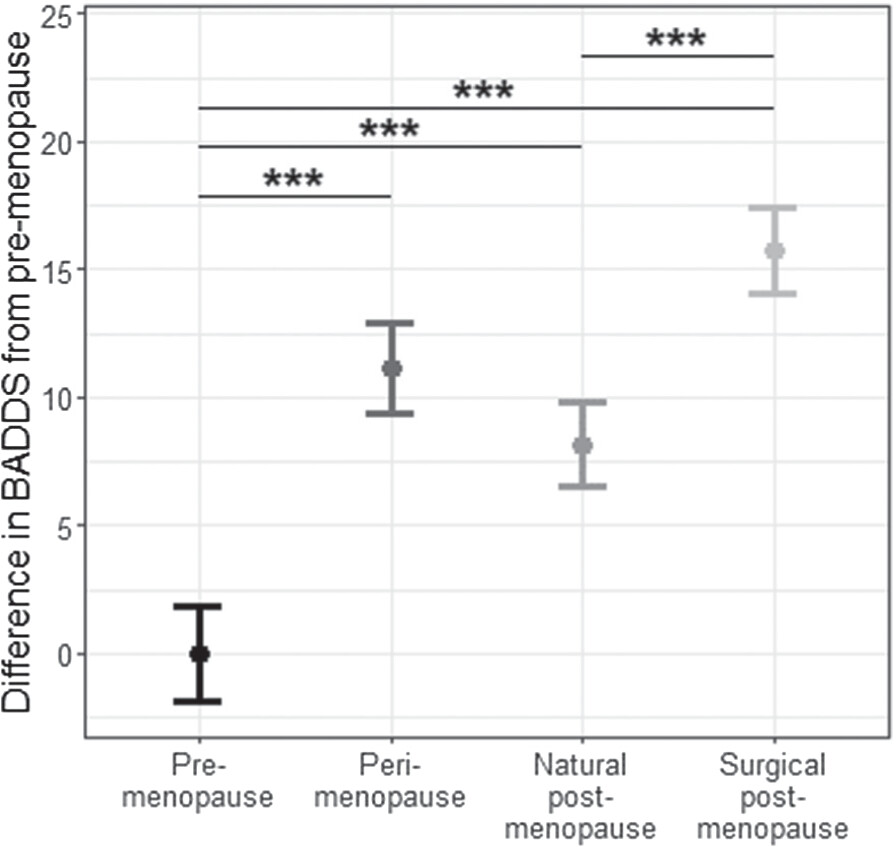

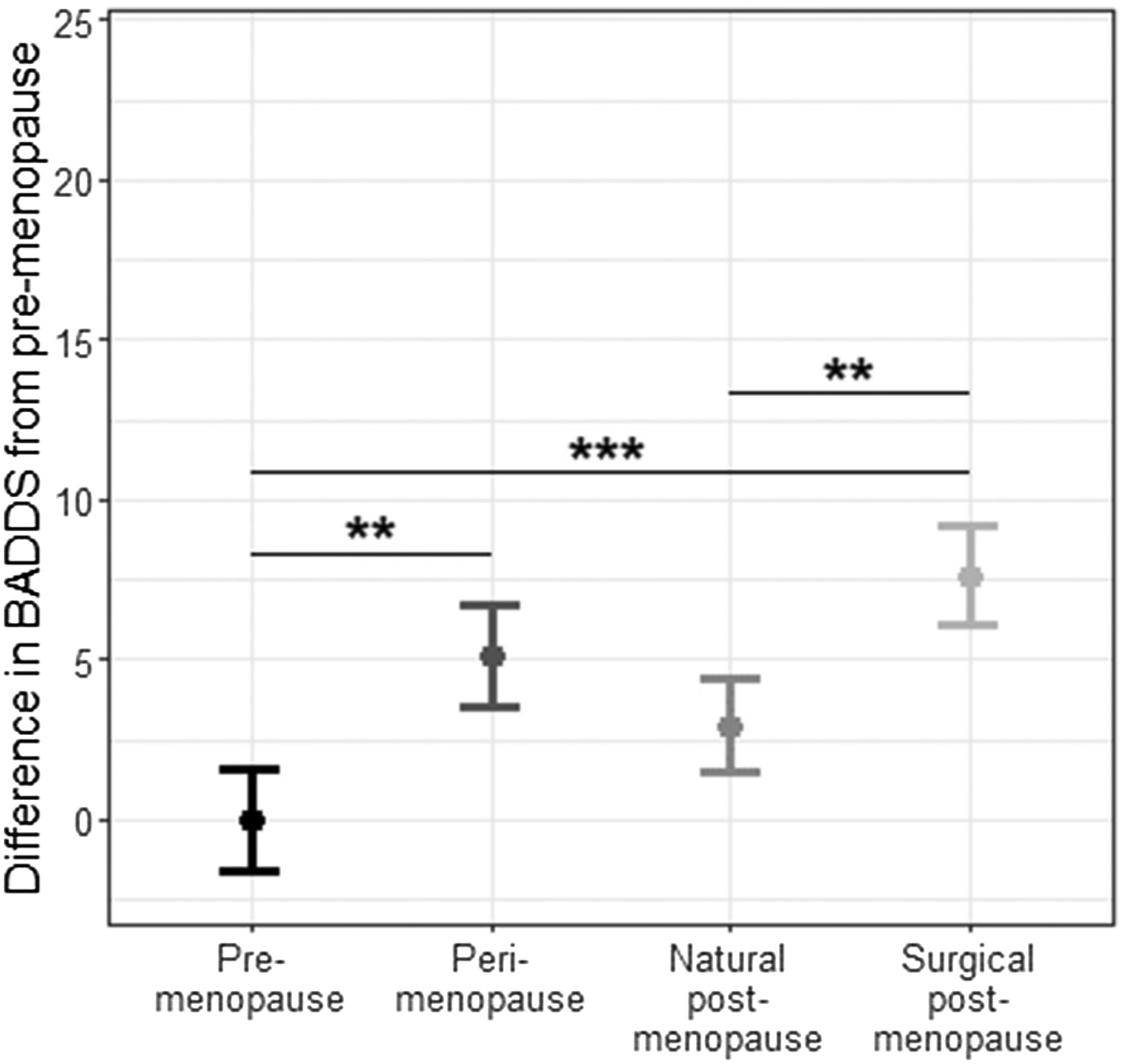

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine executive dysfunction across the menopause transition while considering the potential confounding effects of both postmenopause type and psychological symptoms. Although postmenopause type (natural vs. surgical) and symptoms such as difficulty sleeping, anxiety, and depression are all factors that are known to impact PFC-dependent executive functions, these factors had not been considered conjointly within the same study prior to our investigation. The main conclusions from this research are twofold. First, this study supports the premise that natural and surgical postmenopause are distinct experiences when it comes to difficulties with executive functioning domains of cognition. In statistical models with and without potential confounders, surgical postmenopausal women had BADDS scores that were significantly higher than both premenopausal and natural postmenopausal women. These findings indicate that surgical postmenopause is associated with heightened subjective executive dysfunction. All analyses controlled for age at the time of the study, so these findings are not confounded by surgical postmenopausal participants being younger on average than natural postmenopausal participants (54.2 vs. 59.0 years). Notably, the BADDS scores of surgical postmenopausal women were not significantly different from those of perimenopausal women in either model, suggesting that executive dysfunction is similar between these groups. Second, psychological symptoms – such as sleep disruption, anxiety, and depression – are critical confounders of the relationship between the menopause transition and executive dysfunction that need to be considered. Specifically, when these variables were added as covariates in our model, BADDS scores in natural postmenopausal women no longer significantly differed from premenopausal women, indicating that, in women who undergo menopause naturally, self-reported executive dysfunction does seem to improve after the perimenopause peak in executive function difficulties. However, BADDS scores in natural postmenopausal women were not significantly lower than in perimenopausal women, who still had higher BADDS scores than premenopausal women, suggesting that this recovery in natural postmenopause is only partial. Together, these findings support the conclusion that executive functioning after perimenopause may partially recover to premenopausal levels, but only for natural postmenopausal women and only when accounting for the confounding effects of important psychological symptoms – namely, difficulty sleeping, anxiety, and depression.

In this study, cancer and chemotherapy history did not explain why surgical postmenopausal women report worse executive dysfunction, as these variables were not significantly associated with BADDS scores in models adjusted for age, education, and ADHD. This finding emphasizes the relevance of the psychological covariates we considered (difficulty sleeping, depression, and anxiety). The absence of an effect of chemotherapy on BADDS is consistent with past research that found a history of chemotherapy did not impact BADDS scores among women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutations who had undergone risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy [

24]. However, the prevalence of chemotherapy was low among participants in the present study (

Table 2), possibly limiting our ability to detect an association with BADDS scores. Although cancer and chemotherapy history are still important to consider when investigating cognitive impairment in surgical postmenopausal women, studies on cancer-related cognitive impairment have largely disagreed on the extent to which cancer and chemotherapy impair cognition and which domains of performance are most affected and for how long [

18]. The lack of a significant effect of cancer or chemotherapy on BADDS scores emphasizes the importance of difficulty sleeping and clinically significant levels of anxiety and/or depression on executive dysfunction. Interestingly, the prevalence of these confounders was highest among surgical postmenopausal women and perimenopausal women, further highlighting the similarities between these two groups.

Although the psychological symptoms examined in this study are clearly relevant to executive function across the menopause transition, it is not possible to determine whether the relationship is causal and, if so, the direction of that causality. For example, hormonal changes associated with the menopause transition increase sleep difficulties and symptoms of anxiety and depression, which may then impair executive function [

23,

27,

42]. Alternatively, or additionally, the menopause transition may increase executive dysfunction, leading to difficulty sleeping and depression and anxiety symptoms due to stress and reduced quality of life stemming from cognitive difficulties [

4]. Difficulty sleeping and anxiety and depression symptoms may also have independent effects on, or be independently affected by, executive dysfunction. Future studies designed to test for mediation effects are necessary to disentangle the causal relationship between psychological symptoms and executive function during the menopause transition, which may be bidirectional. Future research should also consider more detailed measures of the psychological variables examined in this study, as well as others not investigated here. For example, using a validated metric for sleep like the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [

43] would allow for an investigation into how the frequency, severity, and nature of sleep difficulties are associated with executive functioning difficulties. Vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flashes, are also common during the menopause transition and are associated with greater self-reported struggles with cognitive function [

4].

Despite the important contributions of this study for understanding the role of potential confounders in the relationship between cognition and menopause, four main limitations are critical to consider. First, all measures were assessed via self-reports, which are more susceptible to participant biases than objective measures. While the BADDS has been used to accurately assess severity of ADHD symptoms and efficacy of ADHD medications in clinical trials [

44,

45], previous research has shown that perceptions of cognitive function do not reliably map onto concurrent measures of cognitive task performance [

46,

47]. However, the BADDS has the advantage of being able to gauge perceptions about multiple domains of executive functioning quickly within the same instrument, including ability to initiate engagement with a task, maintain focus on the task, regulate emotions that may interfere with focus, and utilize working memory to sustain performance [

44,

45]. By contrast, objective tests of cognitive performance are time consuming and limited to measuring a specific domain of cognition. Utilizing the BADDS allowed us to observe that menopause stage and type did not clearly relate to perceived deficits on particular subdomains of executive functioning over others but rather was more important for perceptions of global executive functioning (total BADDS scores). Furthermore, subjective reports of cognitive difficulty are relevant to perceived quality of life [

45] and have been shown to predict future declines in objective measures of cognitive performance [

48]. Self-reports of cognition are therefore important to consider in research and clinical practice, as they are highly relevant to menopausal women’s quality of life in real-world contexts, such as in the workplace.

The second limitation is that we sampled participants cross-sectionally rather than longitudinally, meaning that we compared groups of participants in different stages and types of menopause rather than measuring changes in executive functioning within the same participants across the menopause transition. Longitudinal studies have greater power to detect cognitive changes over time by accounting for individual differences in cognitive baselines and variation in the rate of change [

49,

50]. However, using a cross-sectional design and measuring executive function via self-report also offered several advantages. First, it allowed us to achieve a large sample size within each menopause group, including surgical postmenopausal participants, who are often underrepresented in research on the menopause transition [

51,

52]. Additionally, we were able to avoid repeated cognitive testing over time, which can lead to performance increases due to practice, making it more difficult to isolate the effect of age as well as menopause stage and type on cognitive function [

53]. Nevertheless, a longitudinal study would be necessary to confirm our findings from this cross-sectional study of executive function difficulties.

The third limitation is that this study was not equipped to examine the impact of hormone therapy (HT) use on executive function. A thorough analysis of the effects of HT need to include details such as type of HT, when HT was initiated, and duration of use, both according to chronological age and relative to menopausal stage and type. These details about HT were not possible to ascertain in this cross-sectional survey study. However, HT during the menopause transition is important to consider given previous findings that hormonal birth control [

54,

55] and HT [

8,

56] may impact cognitive function. However, the directionality of HT effects on cognition are complex as HT during menopause can be either beneficial or detrimental depending on the cognitive domain examined [

17] and/or the timing and duration of HT use [

20,

56–

58]. For instance, estrogen therapy may benefit cognition if started during perimenopause but not postmenopause, though results are inconclusive [

14,

15,

56]. For surgical postmenopausal women, estrogen therapy benefits cognition if initiated prior to appro

ximately age 50, but the efficacy declines with age [

56]. However, estrogen is contraindicated for some postmenopausal women, such as those at high risk for breast cancer [

59]. More research into the use of HT for cognition in postmenopausal women, including the timing of treatment (according to chronological and reproductive age) and the associated risks vs. benefits, is needed. Given the complexity of the relationship between the menopause transition and executive function, it will be important in future studies, especially longitudinal ones, to evaluate the impact of HT.

Lastly, the fourth limitation is that the findings from this study primarily come from White, educated, English-speaking women who had access to the internet to complete the online questionnaires. E

xperiences and symptoms during the menopause transition can vary in different countries [

60] and depend on social and cultural factors [

61–

63]. Future investigations should consider postmenopause type (natural vs. surgical) and psychological symptoms in a broader, cross-cultural sample of participants.