Delirium is a complex, acute, and frequently reversible impairment of consciousness, occurring in response to one or more physiological and/or pharmacological etiological insults. It occurs in approximately one in five hospitalized patients

1 and is independently associated with poor outcomes in the form of functional decline, prolonged hospitalization, increased need for institutional care, and elevated mortality and healthcare costs.

2 Despite its high prevalence, delirium is often underrecognized and undertreated because of the complex nature of its symptoms, including their variability and fluctuation over time.

2 The phenomenological profile of delirium varies somewhat across clinical populations and healthcare settings,

3 but recent studies suggest that “core” symptoms (attention deficits, sleep–wake cycle disturbance, motor-activity changes, language and thought disturbances) occur more consistently than other, less-common symptoms (psychosis, affective changes).

3,4 Severity of inattention correlates highly with other common features

4 and is a cardinal and required symptom of delirium in diagnostic systems such as DSM and ICD. The interrelationship between the various symptoms of delirium has been studied using factor analysis, but most studies have used the Delirium Rating Scale (DRS) or Memorial Delirium Rating Scale (MDAS).

5–13 One report used the Delirium Rating Scale, Revised-98 (DRS–R98), which was designed specifically for detailed phenomenological research.

14Studies from developed countries emphasize older populations from geriatric and palliative-care settings where particular etiologies and confounding effects of comorbid dementia are prominent. As such, these findings may not generalize to non-Western populations, where delirium is more common in younger subjects and has different etiological underpinnings.

15 Studies from developing countries are few, even though delirium is a common diagnosis among psychiatric referrals.

15,16 With this background in mind, we studied the phenomenology and etiological underpinnings of delirium occurring in a large teaching hospital in Northern India by use of standard assessment methods.

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Profiles

We assessed 100 patients with DSM-IV delirium who also met the DRS–R98 cutoff for syndromal delirium. There was a predominance of men (78%). Age range was 16–90 years (mean age: 44.4 [19.4]), with a majority (82%) of subjects younger than age 65. Years of education ranged from 0–20 years, with a mean of 9.2 (4.9). The estimated duration of delirium before assessment ranged from 6 hours to 20 days, with a mean of 2.9 (2.8) days. There was a similar representation of referrals from medical (51%) and surgical wards (49%). At the time of assessment, the number of medications received ranged from 0 to 9, with a mean of 4.11 (1.7) per patient; 13 subjects were already receiving psychotropic medications to treat delirium, with 6 taking benzodiazepines; 4, antipsychotics; and 3, both benzodiazepines and antipsychotics.

In almost all cases, the delirium could be attributed to a definite etiology (92%), with a mean number of etiologies of 3.2 (1.0) per patient (range: 1–6). The frequency of etiological categories of delirium as measured on the DEC were (in descending order): endocrine-metabolic disturbance (N=70), infectious (N=45; CNS:11, and systemic: 34), organ failure (N=28), drug-related (N=29; intoxication: 7, withdrawal: 22), seizure-related (N=16), cerebrovascular (N=6), traumatic brain injury (N=5), and other (N=5).

Phenomenological Profile

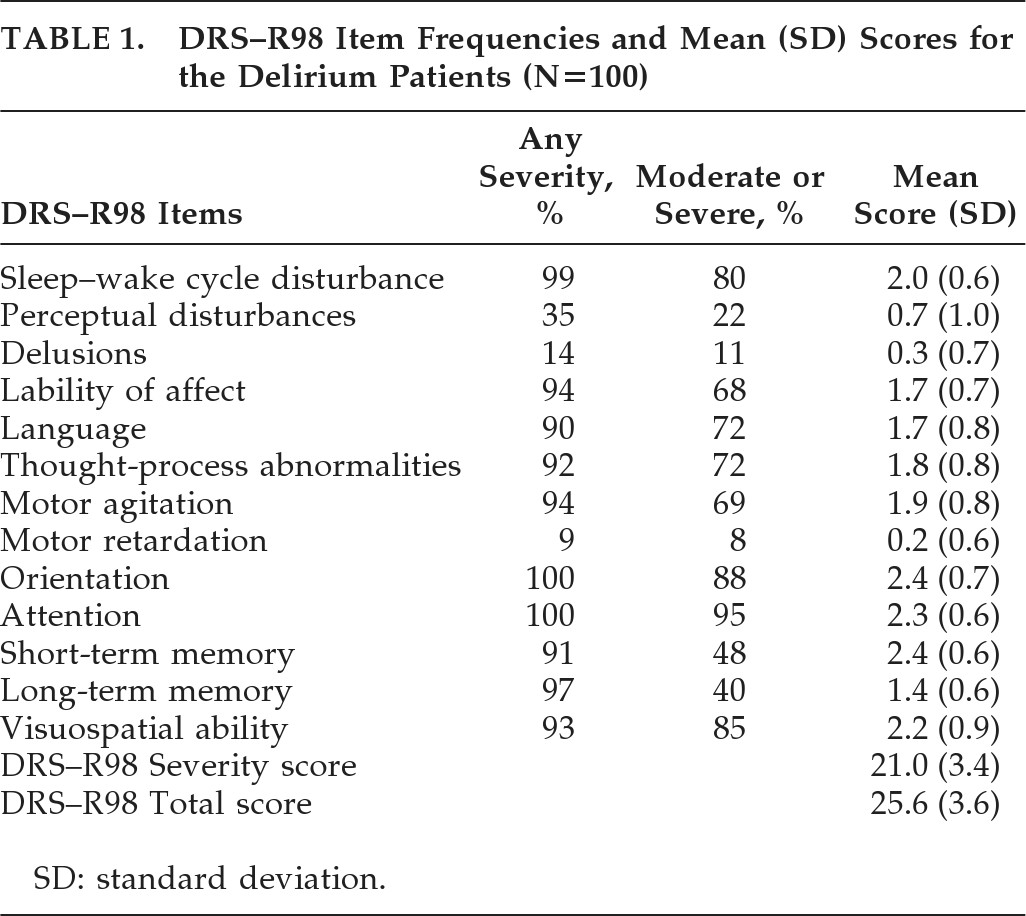

The DRS–R98 Severity score was 21.0 (3.4), and the DRS–R98 Total score was 25.6 (3.6); range: 19–34. The ratings for individual DRS–R98 items are shown in

Table 1. Mean Severity scores were highest for sleep–wake cycle, orientation, attention, short-term memory, and visuospatial ability; and next-highest for language, thought process, motor agitation, and affective lability.

The most common delirium features present at any severity level were disturbances in orientation, attention, sleep, and long-term memory, lability of affect, motor agitation, visuospatial disturbance, thought-process abnormality, and language disturbance (90%–100%); and the least-common were perceptual abnormalities (35%) and delusions (14%). For Frequency, using a Severity cutoff score of ≥2 (moderate or severe), the most common symptoms were attention, orientation, visuospatial ability, and sleep disturbance (80%–95%), with language, thought-process abnormality, motor agitation, and lability of affect (68%–72%) moderately frequent, whereas long-term memory, perceptual abnormality, and delusions (11%–40%) were the least common. Thus, the frequencies generally paralleled the pattern for mean severities.

Factor Analysis

Principal-components analysis initially identified a five-factor solution accounting for 66% of the variance in DRS–R98 scores. These (items, eigenvalues, and variance) were the following: Factor 1 (cognitive symptoms, 3.68; 23%), Factor 2 (language and thought-process abnormality, 2.48; 15.53%); Factor 3 (motor agitation and retardation, 1.83; 11.45%); Factor 4 (sleep disturbance, perceptual abnormalities, and delusions, 1.21; 7.59%), Factor 5 (lability of affect, 1.08; 6.77%).

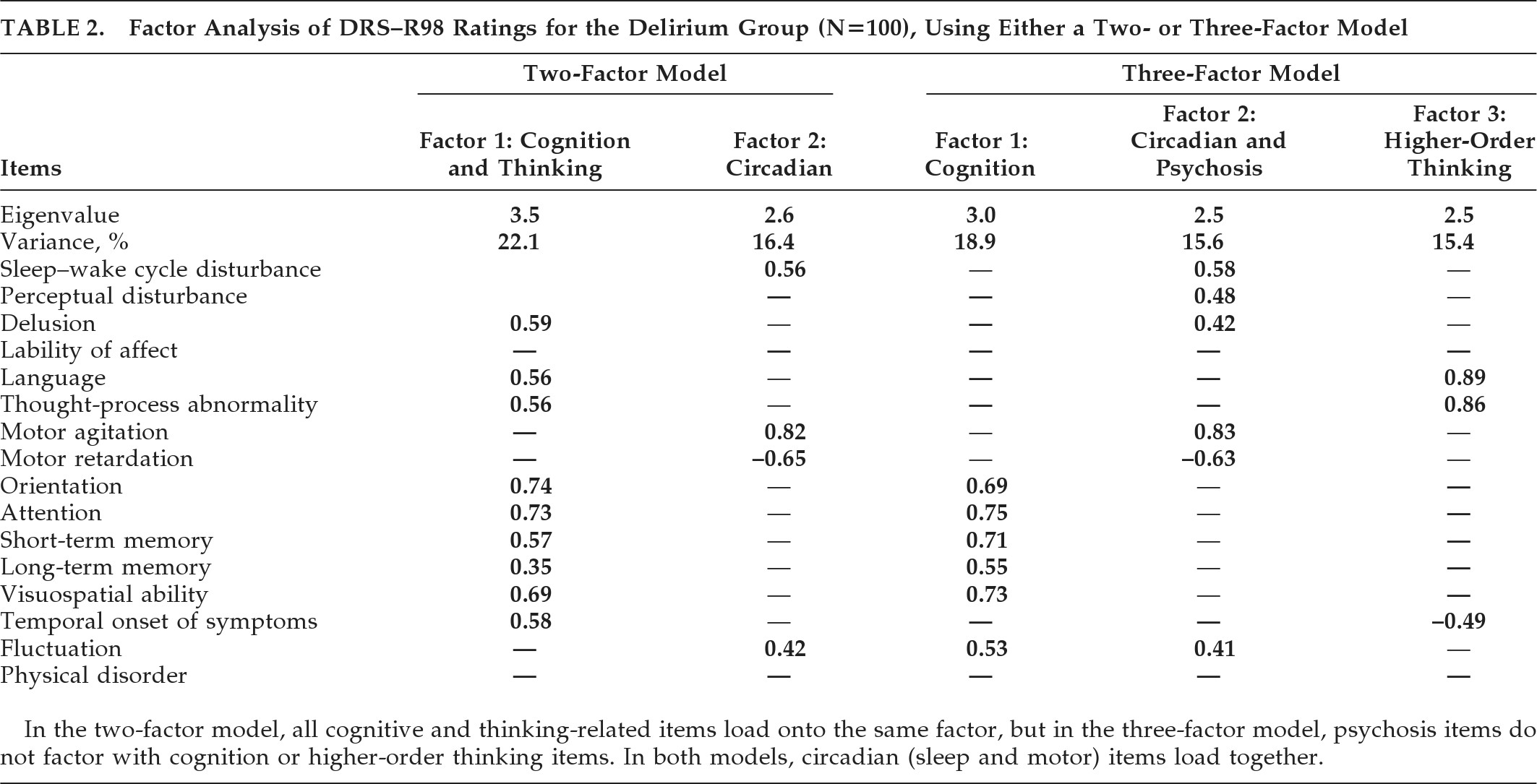

In order to identify a factor solution accounting for maximum variance with the simplest factor structure, we generated two- and three-factor solutions (

Table 2). For both solutions, cognitive items loaded with each other and dominated the major factor. The main difference between the two models was that disturbances of higher-order thinking (language, thought-process abnormalities) occupied a separate factor in the three- factor solution but were subsumed into the Cognitive factor in the two-factor solution. In both solutions, motor items and sleep–wake cycle disturbances dominated a separate factor, although, in the three-factor model, they loaded with the two psychosis items. Overall, the three-factor solution was preferred because it accounted for a higher percentage of variance and was consistent with the literature and the previously proposed model of delirium comprising three core domains; that is, 1) generalized disturbance of cognition; 2) disorganization of higher-order thinking; and 3) alterations to circadian patterns involving sleep–wake cycle and motor activity.

DISCUSSION

We studied the phenomenology of delirium occurring in general-hospital inpatients in a developing-country setting. We used standardized assessment methods, including validated tools for delirium phenomenological assessment. The population studied herein provides a unique insight into the clinical profile of delirium occurring in a relatively younger population, without the influence of comorbid dementia, and with limited previous exposure to delirium treatment with psychotropic agents, both of which can considerably affect delirium profile.

The frequency and severity of long-term memory impairment was lower than that reported in populations that include many elderly patients. The almost-exclusive motor presentation of hyperactivity probably reflects this being a referral population where patients with behavioral disturbance and, especially, agitation are most often referred, but also might reflect the predominance of men and younger persons. We found a predominance of symptoms of attention, visuospatial ability, orientation, sleep–wake cycle, thought-process, language, motor agitation, and lability of affect in our delirium cohort.

Studies of the delirium clinical profile, using well-validated tools in C/L settings, are relatively rare, with most work focusing on elderly medical and surgical or palliative-care populations.

3 The frequency of delirium in this group was higher than in other studies, where delirium was noted in 10%–28% of referrals,

23–25 but these studies may have been influenced by the fact that they were conducted in a newly-established C/L service

23 or used retrospective methods to identify cases.

25 Meagher

26 reviewed motor-subtype patterns in delirium studies and highlighted the occurrence of relative hyperactivity of clinical presentation in C/L referral versus elderly medical, palliative-care, and ICU populations.

Previous studies suggest that the clinical presentation of delirium is largely similar, but may have subtle difference in pediatric populations. Turkel et al.

27 reported that children experience a similar range of symptoms as adults, but with less-frequent delusions and greater symptom fluctuation, sleep–wake cycle disturbance, affective lability, and agitation, although this finding needs to be interpreted with caution because of study-design limitations and comparisons with the adult literature. Leentjens et al.

28 found more severe cognitive symptoms in geriatric delirium, as compared with adults, and more severe hallucinations, delusions, sleep–wake cycle disturbance, and lability of mood in pediatric age-groups. Our work in a relatively young adult/late adolescent population with delirium identified a relatively low frequency of overt psychosis, as has been reported across most adult studies, but with prominent affective lability and motor agitation. The reason for this difference is not discernible in our study design, which studied a referral sample and requires an incidence design.

This study also highlights the frequency of disturbances to higher-order thinking, as evidenced by the finding that 93% of patients had evidence of either disturbed language or thought-processes measured on the DRS–R98. This concurs with findings from recent studies in other populations

4,14,29 that such disturbances are key elements of delirium and should be included in diagnostic criteria. This consistent expression of thought-process abnormalities suggests that the de-emphasis of disorganized thinking as a diagnostic criterion between DSM-III-R and DSM-IV may warrant reexamination during the development of delirium criteria for DSM-V and/or ICD−11.

30 However, any reintroduction of disorganized thinking as a key criterion would require the development of more reliable ways of assessment for nonpsychiatrists, given that this was a key reason for its removal after DSM-III-R.

31Factor-analysis reports to-date mostly used the original DRS and/or MDAS, and mostly identified two- or three-factor solutions, typically with a composite cognitive and one-or-more neurobehavioral factors.

6–14 Our findings are not inconsistent with these previous reports, but the DRS–R98 offers advantages for broader phenomenological assessment and delineated a three-factor model that parallels the proposed three core domains of delirium: attention, circadian, and higher-level thinking.

4,14,32 Only one previous study

14 has reported the factor structure of delirium phenomenology using the DRS–R98, performed in a Columbian general-hospital inpatient population, and identified a two-factor solution, but this study included a comorbid population with relatively smaller number of patients with full syndromal delirium.

Although recent work has reemphasized the central role of attentional disturbance in delirium,

4,33 this study affirms the prominence of circadian disruptions of sleep–wake cycle and motor activity, as well as higher-order thinking. This can assist in the development of descriptions that are representative of the breadth of the syndrome of delirium, while also allowing for more consistent detection in clinical practice. The presence of three core and discrete symptom clusters contrasts with the current DSM-IV definition of delirium, which emphasizes attentional disturbance in the context of acute onset and fluctuating course, but does not require circadian and higher-level thinking impairments. This report supports previous findings that these other two domains are core and need to be considered in delirium.

Limitations

Although this population had minimal exposure to psychotropic medications to manage delirium, we were not able to control for beneficial or adverse effects of medications prescribed for this medically ill population on the phenomenology of delirium. We excluded dementia based on existing diagnosis, although not with a formal tool, although very few patients were in a vulnerable age-range for common degenerative dementias.