Primary focal dystonia (FD) is a movement disorder characterized by involuntary muscle contractions and abnormal postures, whose pathophysiology is related to abnormalities in striato-thalamo-cortical circuitry.

1 Blepharospasm and cervical dystonia are the most common forms. Recent studies suggest that motor symptoms are associated with a wide spectrum of non-motor features, such as a distinct neuropsychiatric profile, belonging mainly to the anxiety spectrum.

2 However, it is still not clear whether these manifestations are the result of the associated social and physical disability or whether they are linked to a shared pathophysiology.

3The current dominant model of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) focuses on abnormalities in cortico-striatal circuitry, with particular emphasis on the orbitofrontal-striatal-thalamic network.

4 Evidence from cognitive and neuroimaging studies (functional and structural MRI and PET) have generally been supportive of these general theoretical models.

5 Early PET studies measuring brain function via cerebral glucose metabolism showed significantly elevated metabolic rates in whole cerebral hemispheres, the heads of the caudate nuclei, and the orbital gyri in patients with OCD.

6 A quantitative, voxel-level meta-analysis performed on fMRI case–control studies of OCD provides clear support for abnormalities of orbitofronto-striatal regions in OCD.

7 The same networks are deeply involved in a number of movement disorders,

8 suggesting the possibility that a number of non-motor manifestations of movement disorders may be biologically-driven, with special emphasis on obsessive-spectrum symptoms. Various authors have reported that OCD, or subsyndromal OCD (OCS), are overrepresented in FD patients,

9–11 as compared with healthy-controls. The hypothesis of a shared pathophysiology between FD and OCD/OCS was tested in a small sample by Broocks et al.,

12 who first used hemifacial spasm (HFS) patients as an ideal control group because of HFS's phenomenological similarities to blepharospasm in terms of repetitive involuntary movements, despite different underlying mechanisms—namely, the ectopic excitatory activity of the facial nerve, possibly originating from a vascular compression. The authors reported that patients with blepharospasm differed from patients with HFS with respect to OCS, but with less difference at the disorder-diagnosis level (i.e., a DSM diagnosis of OCD). On the contrary, other authors failed to identify any difference in terms of either OCS or OCD between FD and HFS patients.

13,14Most of these studies have a number of limitations, such as the lack of a careful description of psychopathology. Therefore, we aimed to describe OCD phenomenology in patients with FD, HFS, and healthy-control participants, with all groups matched for age and gender, focusing on psychopathological domains of OCD and associated psychopathology.

METHOD

From a number of patients consecutively referred to the Botulinum Toxin Clinic of the Division of Neurology, Amedeo Avogadro University, Maggiore Hospital in Novara, Italy, we identified subjects with a diagnosis of HFS and FD, matched for age and gender. All patients were treated with Botulinum toxin A and were evaluated before and after its administration. We also recruited 23 healthy subjects matched for age and gender. They were selected from all medical specialties in order to reduce possible biases.

The diagnosis of dystonia met standard criteria.

15 All subjects enrolled in the study underwent a neuropsychiatric evaluation by an experienced neuropsychiatrist (MM). Mental status examination and neurological examination were conducted in all subjects; neuroimaging procedures (e.g., MRI or CT scans) were performed only in the patient group. Subjects younger than 18 years of age, with a reading level less than 6th grade, with learning disabilities, or a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score <24 were excluded. After the procedure was explained, participants gave written informed consent.

All subjects were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Version (SCID–I/P), the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS),

16 the Symptom Checklist–90-Revised (SCL–90),

17 and the Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Self-Report, Lifetime Version (SCI-OBS-SR).

18 In patients with a DSM diagnosis of OCD, severity of symptoms was rated with the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (YBOCS).

19 All questionnaires were administered in a standardized form and in the same sequence.

The Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Self-Report, Lifetime Version (SCI-OBS-SR) consists of 183 items, grouped into seven domains: childhood/adolescence experiences, doubt, hyper-control, attitude toward time, perfectionism, repetition and automation, and specific themes. The last domain consists of 52 items and comprises a checklist of obsessive-compulsive thematic contents: contamination, cleaning, sexuality, existential attitudes toward religion, aggressiveness, impulsiveness, and somatic themes. We adopted the SCI-OBS-SR because we were interested in the specific psychopathological domains explored by this instrument; in fact, it was developed to explore not only core aspects of OCD but also atypical manifestations and associated symptoms.

18 In fact, the SCI-OBS-SR was developed to complement the categorical diagnosis with a new, dimensional approach that gives clinical significance to a number of manifestations that may play an important role in modifying the typical presentation of a psychiatric disorder and interfere with treatment. Moreover, it has several advantages, including the lifetime interval, the time- and cost-effectiveness when compared with face-to-face interview, its validation in both English and Italian, and its successful use in other settings.

The Symptom Checklist 90–R (SCL–90-R) is a self-report questionnaire widely used for psychopathological screening; it is organized into 10 primary symptom dimensions: somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism, and sleep. Also, three global indices are reported: the Global Severity Index (GSI), indicating the overall level of psychological distress; the Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI), measuring the intensity of the experienced symptoms; and the Positive Symptom Total score (PST), representing the number of reported positive symptoms.

All groups were compared for demographic and clinical variables, YBOCS, HADS, SCL–90-R, and SCI-OBS-SR total and subscale scores. Chi-squared analysis or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical data; ordinal and linear data were assessed by nonparametric tests. Correlations were tested with two-tailed nonparametric procedures. The standard error (SE) was set at 0.016, considering multiple group comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 15 for Windows, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

A total of 60 subjects were evaluated (FD: 19; HFS: 18; HC: 23), mean age: 60 years (54 women). In the FD group, 11 patients had cervical dystonia; 8 patients, blepharospasm. Their demographic and clinical features are reported in

Table 1. There were significantly higher rates of personal and family psychiatric history in patient groups (both FD and HFS), versus HCs. The prevalence of OCD was 26% in patients with FD and 28% in patients with HFS, significantly higher than in HCs (FD: 5/19; HFS: 5/18; HC: 0/23). Subjects with OCD did not differ in terms of age, gender, or YBOCS scores (FD+OCD: 8.8 (2.9); HFS+OCD: 10.4 (3.9). Of all patients with OCD, only three were newly diagnosed, with a YBOCS score of 17. All other subjects had already received a previous diagnosis of OCD in young adulthood, with three patients taking SSRIs in combination with benzodiazepines, one in combination therapy with SSRIs and lithium, and the remaining in psychotherapy-only. In these patients, YBOCS scores ranged between 7 and 9. Subsyndromal OCD (OCS), defined by an SCI-OBS-SR score over 59,

18 was diagnosed in six patients. There were no difference in clinical and demographic variables, HADS, or SCL–90-R scores between OCS and OCD.

Patients with FD and HFS were not receiving any treatment for their movement disorder apart from Botulinum toxin. There was no between-group difference in HADS scores and SCI-OBS-SR total scores (

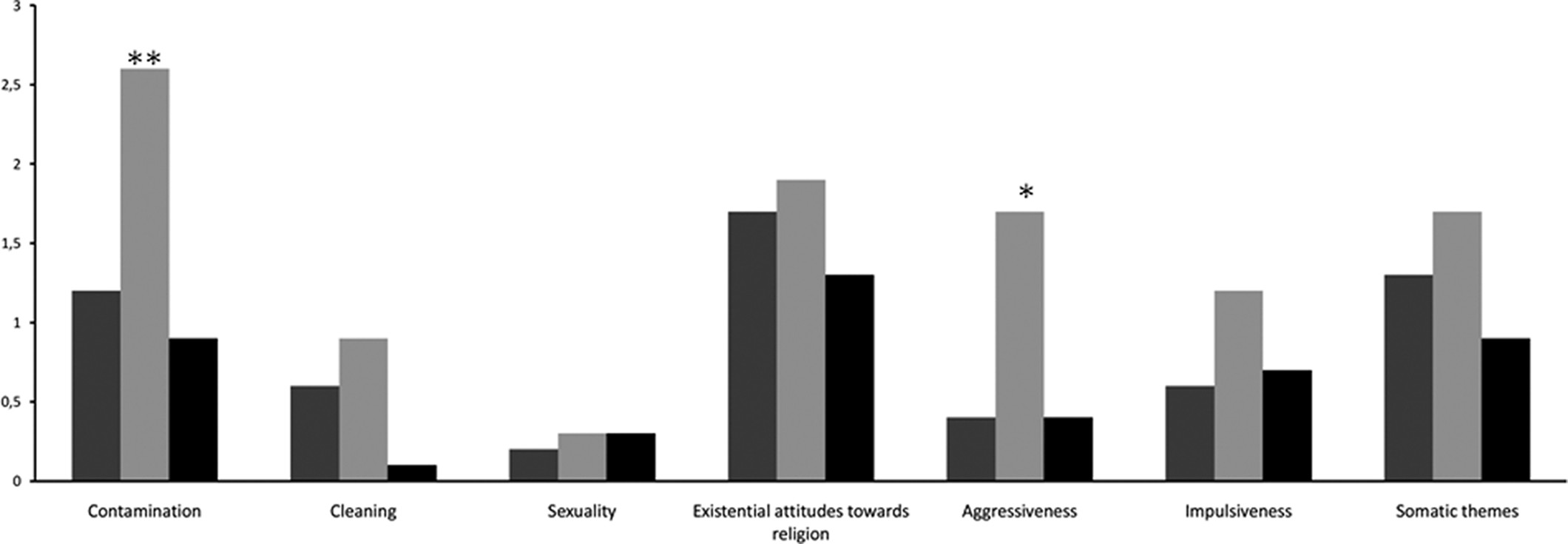

Table 1). However, there were significant between-group differences in the thematic content of obsessive symptoms (

Figure 1). In particular, HFS patients showed higher scores for Contamination (HFS: 2.6 [1.7]; FD: 1.2 [1.3]; HC: 0.9 [1.2]; p=0.005) and Aggressiveness (HFS: 1.7 [2.0]; FD: 0.4 [0.7]; HC: 0.4 [0.7]; p=0.024), as compared with patients with FD and HC. There were no between-group differences in the majority of the SCL–90-R dimensions, except that there were significantly higher scores for Somatization (FD: 13.7 [7.8]; HFS: 13.0 [8.9]; HC: 7.0 [5.7]; p=0.009) and Positive Symptom Distress Index (FD: 1.8 [0.5]; HFS: 1.5 [0.5]; HC: 1.1 [1.2]; p<0.001) in patients with FD and HFS, as compared with HCs (

Table 1).

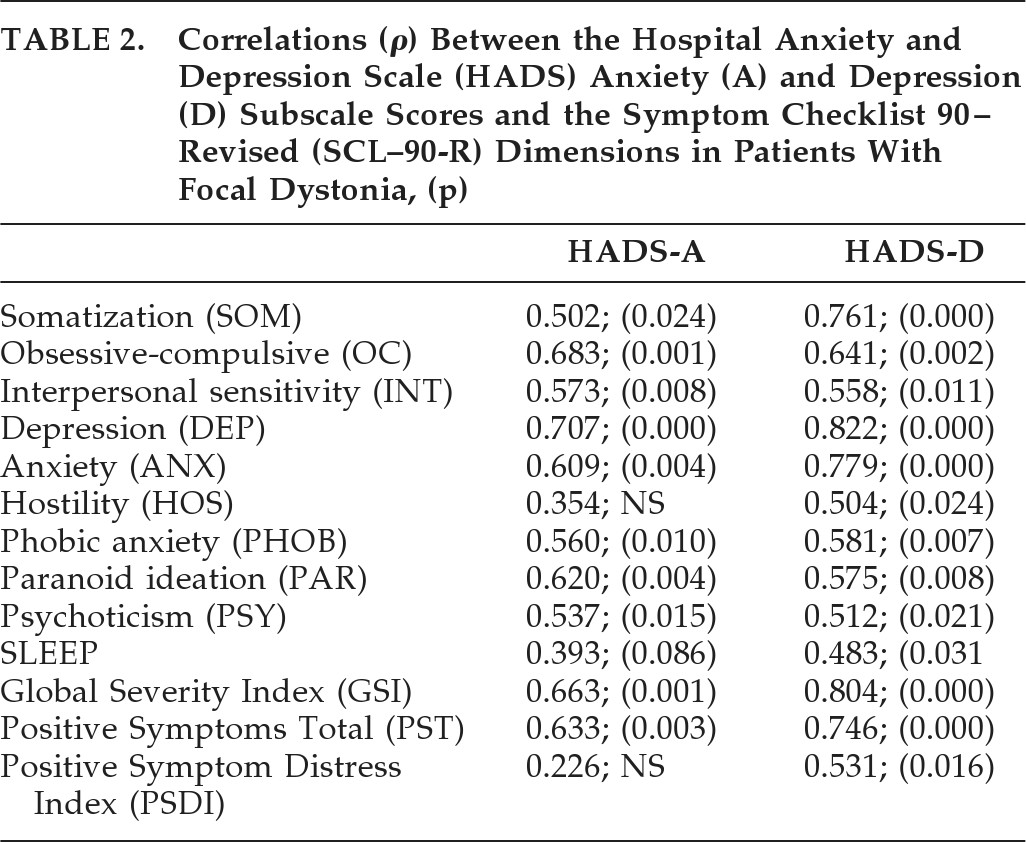

Among FD patients, age was inversely correlated with the SCI-OBS domain Aggressiveness (r = –0.592; p=0.008), and age at onset correlated negatively with the domain Impulsiveness (r = –0.483; p=0.036), yet there was a significant correlation between the Anxiety and Depression subscales, as measured by the HADS, and a number> of psychopathological dimensions on the SCL–90-R (

Table 2).

Among HFS patients, age and age at onset inversely correlated with the SCI-OBS domain Doubt (r = –0.615, p=0.011; r = –0.570, p=0.021, respectively), yet there were no significant correlations between SCL–90-R dimensions and HADS subscales apart from an expected correlation between similar dimensions explored by the two instruments.

DISCUSSION

In general terms, it has to be stated that FD and HFS are not burdened by a significant psychopathological weight, being that the majority of measures are quite similar among the three groups. However, our study confirms that OCD and OCS are more common in both focal dystonia and hemifacial spasm than in healthy controls,

9–11,20 and it suggests that such manifestations have different nuances in the two groups. In our opinion, this point is of particular interest. The association between HFS and OCD/OCS is still controversial.

14 As previously stated, it has been suggested that the association of OCD with FD might result from a common pathophysiology, namely, the presence of abnormalities in the striato-thalamo-cortical circuits. In the case of HFS, it is difficult to hypothesize a common pathophysiology. However, our study clearly shows an increased prevalence of OCD and OCS in patients with HFS and the presence of specific thematic content such as “contamination” and “aggressiveness” as compared with FD subjects and HC. Moreover, age at onset of the disease correlated with the domain Doubt of the SCI-OBS. All these domains are classic core features of OCD, and it is unlikely that they could result from other variables, such as the degree of social and physical disability.

21 “Contamination” refers to the uncontrollable fear of dirt, germs, bacteria, or body excreta; “Aggressiveness” refers to intrusive thoughts about physical or verbal assault on self or others, accidents, death, or calamities; “Doubt” is the lingering inclination not to believe that a task has been satisfactory accomplished.

22 Other studies of our group have pointed out that different brain circuits underlie different thematic contents when OCD is associated to different brain disorders.

23 In such a case, it is tempting to speculate that OCD symptoms in HFS might be the result of basal ganglia-disturbed neural activity, possibly secondary to a loop linking peripheral afferences, via the thalamus, to the basal ganglia. In other words, the peripheral phenomenology may antidromically activate CNS circuits similar to those primarily activated in FD, thus contributing to the development of similar non-motor symptoms. In this regard, functional neuroimaging studies would be warranted to bear out such a hypothesis.

As far as the general psychopathological profile is concerned, there were no between-group difference among focal dystonia, hemifacial spasm, and healthy-controls with regard to HADS and SCL–90-R scores apart from the Somatization and PSDI domains, probably reflecting the physical distress arising from the movement disorder per se, rather than a peculiar psychopathology. Similar results were obtained by Broocks et al.

12 and previously by Scheidt et al.

21 However, it is of interest that, in the FD group, anxiety and depression scores, as measured at the HADS, significantly correlated with the majority of SCL–90-R dimensions (

Table 2), suggesting that mood and anxiety symptoms appear to drive a greater psychopathological load in FD than in HFS. This feature supports the hypothesis of a primary CNS dysfunction underlying both motor and non-motor symptoms in FD.

In conclusion, our study suggests that patients with focal dystonia and hemifacial spasm are characterized by OCD/OCS, usually mild in severity, whose occurrence is probably driven by the interaction between the underlying brain condition and a “fertile ground” (past psychiatric history). However, our results need to be considered keeping in mind the following limitation. The small sample size significantly limits the strength of our findings, but the comparison of three groups matched for age and gender and the detailed psychopathological assessment reinforce the relevance of our findings. Further studies in large and homogenous populations are needed to shed light on the pathophysiology of non-motor symptoms in patients with FD and HFS.