Neuropsychiatric disturbances are a common feature of Huntington's disease (HD), recognized since the earliest descriptions of this condition.

1 A wide range of neuropsychiatric symptoms have been reported, including depression, anxiety, irritability, apathy, perseveration, and psychosis.

2–4 Such symptoms are often a source of considerable distress to affected individuals and their families

5 and have been shown to exert a greater impact on levels of functional disability

6 and quality of life

7 than either motor or cognitive symptoms. With recent advances in understanding the pathogenesis of HD and clinical trials of rational neuroprotective agents finally on the horizon,

8 it is essential that any future treatment should have a beneficial effect on neuropsychiatric symptoms in addition to motor and cognitive aspects of the disease.

Despite their clinical importance, the natural history of neuropsychiatric symptoms and their relationship to the underlying disease-process in HD remain poorly understood. In the past, it was assumed that, unlike motor and cognitive symptoms, neuropsychiatric disturbances are “heterogeneous, episodic, and without clear temporal progression.”

9 More recent studies suggest that HD is characterized by specific clusters of neuropsychiatric symptoms

2,10,11 that may differ in their underlying basis. Research using the Problem Behaviors Assessment for Huntington's Disease (PBA-HD)

2 has demonstrated three symptom clusters, derived from principal-component analysis, reflecting apathy, irritability, and depression, respectively.

2,10 Moreover, cross-sectional analysis demonstrated that the extent of apathy was closely related to duration of illness,

2 and highly correlated with motor, functional, and cognitive indices of disease severity,

12 whereas irritability and depression did not have a clear relationship with these markers of disease progression.

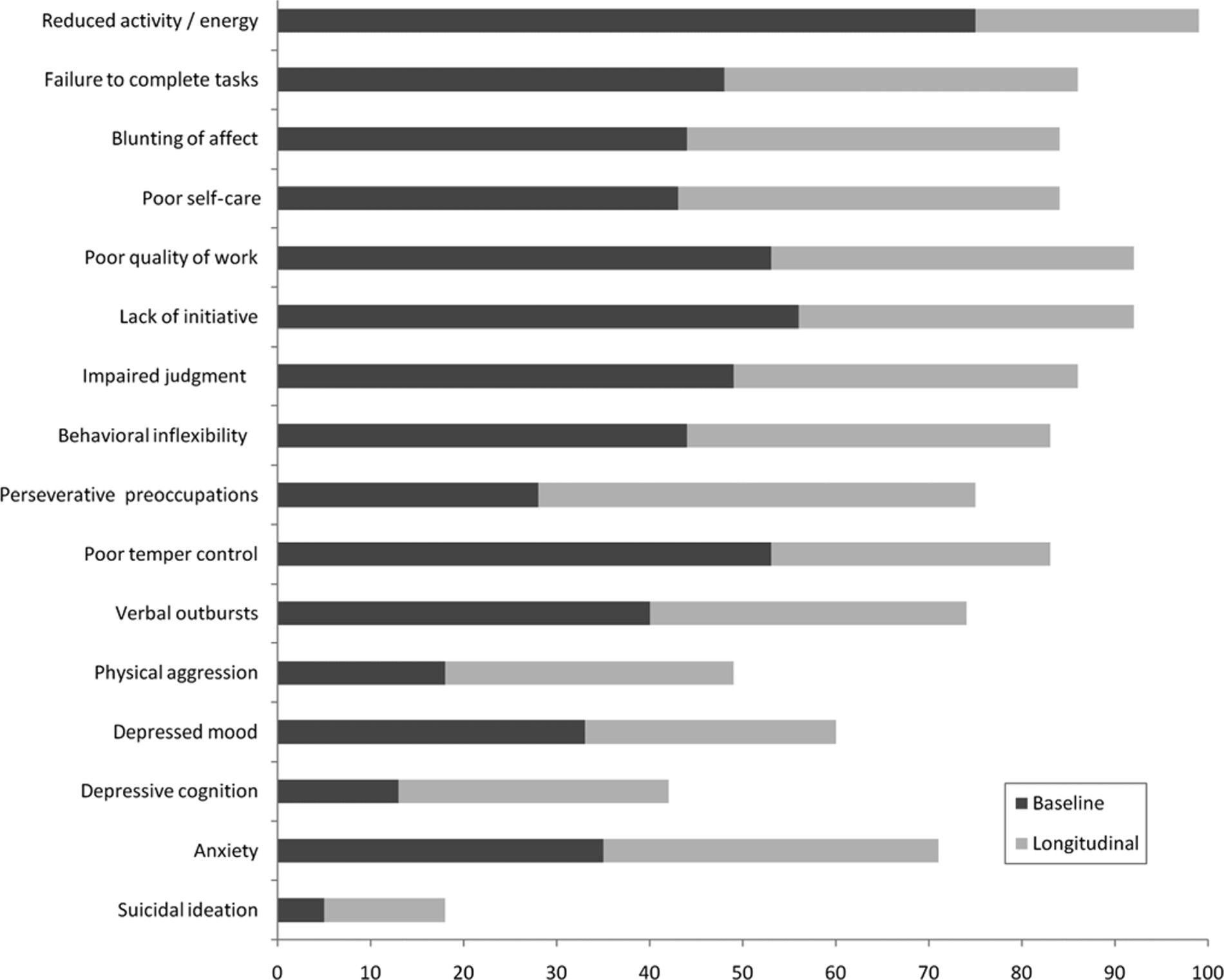

We evaluated 1) the overall prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms at baseline and longitudinally; 2) their pattern of progression over time; and 3) variation in longitudinal changes in relation to disease stage at initial assessment. We anticipated that longitudinal prevalence would be higher than baseline point prevalence. On the basis of previous findings, we hypothesized that apathy would show a clear progression over time. By studying depression and irritability longitudinally, we aimed to shed light on the etiology and natural history of these symptoms.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms was notably higher when consecutive longitudinal assessments were taken into account, as compared with a single baseline assessment. This is an important observation because it suggests that previous cross-sectional studies may have underestimated the prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in HD. Overall, neuropsychiatric symptoms were extremely common in our sample, with some symptoms occurring in 99% of patients and no single patient remaining completely free from such symptoms over the follow-up period.

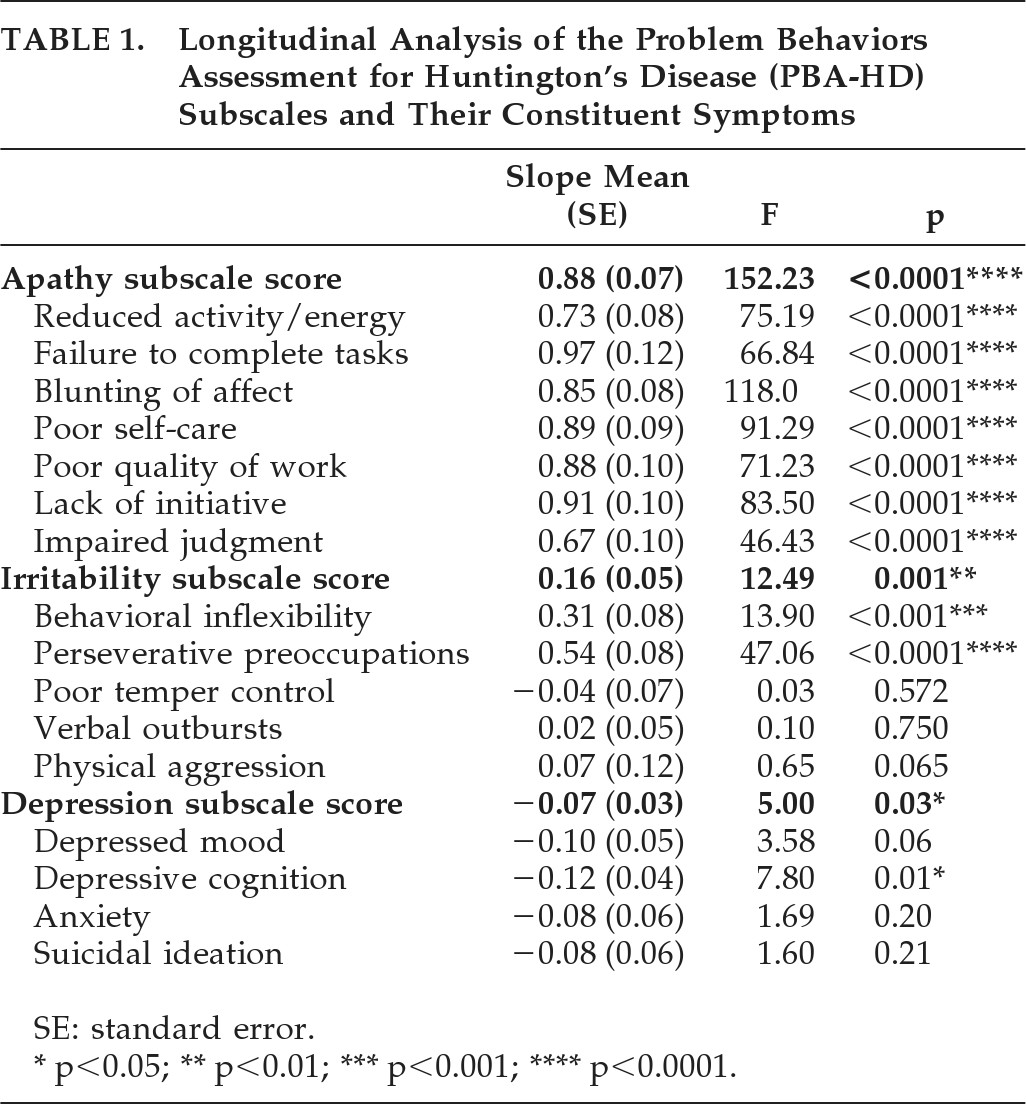

In keeping with our hypothesis, scores on the Apathy subscale and its constituent symptoms showed a progressive worsening over time, a pattern that was evident across all stages of disease. This reinforces our previous cross-sectional findings that apathy was closely related to duration of illness

2 and highly correlated with cognitive, motor, and functional indices of disease severity.

12 Our findings support and extend other cross-sectional observations of greater apathy with increased disease severity.

10–14 Notably, we found apathy symptoms to be present, at least to a mild degree, in almost all patients studied. The inference is that apathy is intrinsic to the evolution and progression of HD, showing a progressive worsening over the course of the disease.

It is useful to view our findings in relation to models of the neural substrate of goal-directed behavior. Levy and Dubois

17 define apathy as “a quantitative reduction in self-generated voluntary and purposeful behaviors” and outline three subtypes: “Emotional-Affective,” “Cognitive,” and “Auto-Activation,” each of which are associated with damage to different parts of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and basal-ganglia circuits. Within this framework, Emotional-Affective apathy gives rise to emotional blunting and loss of interest in previously-motivating activities or stimuli; it is associated with damage to the orbitofrontal PFC and ventral striatum. Cognitive apathy reflects impaired frontal-executive functioning, giving rise to poor planning, organization, and set-shifting, and is characteristic of damage to the lateral PFC and dorsal caudate. Auto-Activation apathy refers to a reduction in self-generated, spontaneous action and thought, and is associated primarily with damage to the dorsomedial PFC and internal segment of the globus pallidus. In HD, the primary site of pathology is thought to be the striatum,

18 which is richly connected to the PFC via a series of parallel cortico-striatal circuits.

19 According to the framework proposed by Levy and Dubois, apathy occurs after basal-ganglia damage because of disruption of the basal-ganglia–PFC circuit, resulting in reductions in both overall activation and temporo-spatial focalization in activation of the PFC. The PBA-HD Apathy subscale used in the present study contained items pertaining to each of the proposed apathy subtypes: emotional blunting (Emotional-Affective), impaired judgment and reduced quality of work (Cognitive), and reduced activity and initiative (Auto-Activation). Progressive and marked impairments were present in all three domains, indicating a fundamental and pervasive deficit of apathy in HD, secondary to striatal-frontal dysfunction.

In keeping with previous cross-sectional studies,

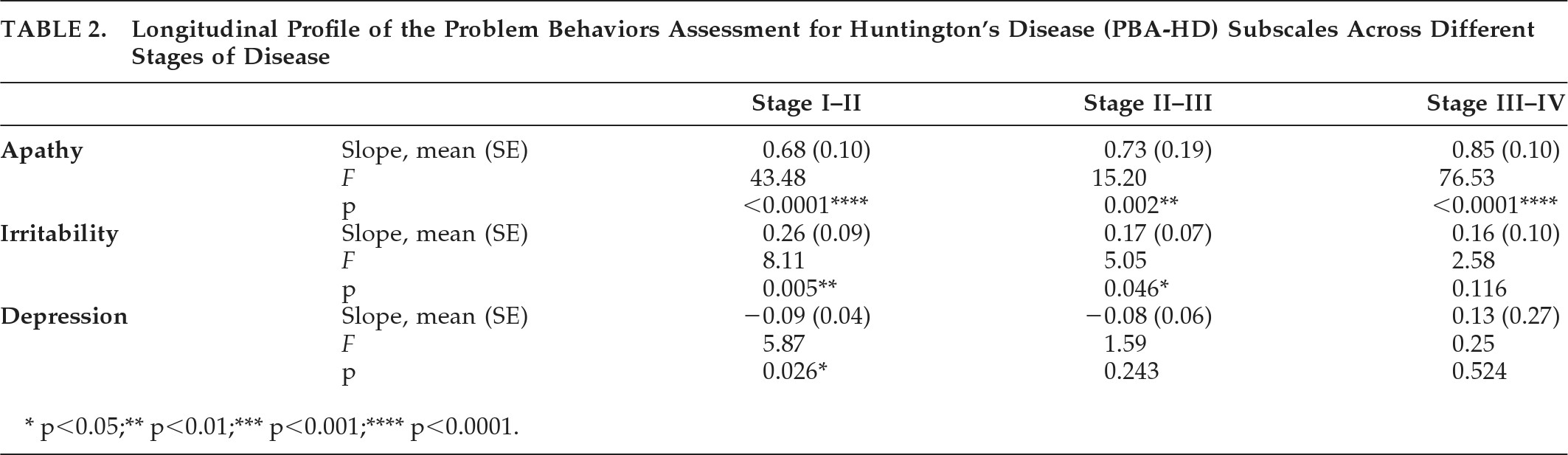

2,3 irritability was very common, with over 80% of patients showing poor temper control and almost 50% reporting some level of physical aggression during the follow-up period. Longitudinal analysis revealed an overall increase in irritability with time. However, this increase did not occur across all stages of disease. Rather, scores on the PBA-HD Irritability subscale showed a significant increase among patients entering the study at Stage I, and a marginally significant linear trend in patients entering the study at Stage II, suggesting that irritability develops in the early stages of HD, reaching a peak (or plateau) by Stage III. Interestingly, this observation is consistent with the finding of a longitudinal increase in irritability over a 4-year period in pre-manifest HD gene-carriers, as compared with non-carriers.

20The most commonly reported irritability symptoms were poor temper control, verbal outbursts, and behavioral inflexibility. It is reasonable to relate these symptoms to the established deficits in frontal-executive functioning in HD. Poor response-inhibition

21 may contribute directly to poor temper control and verbal/physical aggression. Reduced cognitive flexibility

22 may result in patients' becoming increasingly inflexible behaviorally. It is interesting, then, that a longitudinal progression of such symptoms could only be detected in the early stages of HD. One possibility is that irritability is partially controlled by psychiatric medication. Indeed, the study patients were attending a multidisciplinary research and clinical-management clinic, with psychiatric input, and may, therefore, have been more likely to be prescribed psychiatric medication than HD patients in other settings. Another possibility is that there is an interaction between irritability and apathy; that is, irritability and aggression may plateau as apathy and abulia increase.

Depressive symptoms were common, particularly when longitudinal rather than baseline prevalence was examined, with 60% of patients experiencing low mood and 71% experiencing anxiety over the course of the study. However, in contrast to the Apathy and Irritability subscales, scores on the PBA-HD Depression subscale did not show any significant increase over time. Rather, there was a significant reduction in depressive symptomatology in patients entering the study at Stage I and a nonsignificant decline in those entering the study at Stage II. It is necessary to exercise caution in interpreting this observation since, in common with irritability, it is likely that depressive symptoms were at least partially alleviated by antidepressant medication. Nevertheless, the notion that depression is more common in the mild-to-moderate stages of disease is in keeping with the findings of Paulsen et al.,

23 who reported the highest rate of depression in HD patients who were in Stage II of disease. Others,

23 as well as ourselves,

5,12 have previously suggested that rates of depression and anxiety may subside in later stages of disease as emotional blunting increases and insight lessens.

The etiology of depression in HD is intriguing. It would be reasonable to attribute depression to reactive factors in individuals affected by a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disease that has likely already claimed a parent. However, the observation of higher rates of depression in double-blind studies of at-risk gene-carriers, as compared with non-carriers,

24 suggests that HD increases susceptibility to depression, even in the pre-manifest phase of disease. Indeed, greater frontal hypometabolism has been observed in depressed, versus non-depressed HD patients.

25,26 It is interesting, then, that rates of depressive symptoms, although common, were not the ubiquitous sign that apathy appears to be, nor as common as irritability and related symptoms. Our data would seem to suggest that not all patients with HD experience low mood. Further research is required to attempt to validate this finding and to illuminate factors that influence depression in HD, be they genetic, organic, or environmental.

Longitudinal studies of HD have generally focused on motor and cognitive aspects of the condition, with very few addressing specific neuropsychiatric changes. One study reported no significant change on the UHDRS Behavioral Scale over a 1-year interval.

27 A more recent publication of the 12-month longitudinal analysis from the TRACK-HD Study

28 failed to find a significant longitudinal change in apathy, irritability or affect in early HD by use of a shortened form of the PBA-HD. The apparent discrepancy between the present study and previous reports is likely to reflect the longer follow-up period, our use of a more detailed neuropsychiatric interview, and the separation of symptoms into clinically-relevant clusters.

The finding of distinct longitudinal profiles in the three PBA-HD subtypes supports the separation of neuropsychiatric symptoms in HD into distinct clusters. We examined three clusters, based on our previous principal-components analysis of the PBA-HD.

2 A recent study of 1,690 HD patients enrolled in an international multicenter study

29 distinguished four symptom-clusters by principal-components analysis, three of which were similar to the PBA-HD subscales (Depression, Drive/Executive Function, Irritability/Aggression) and a fourth, “Psychosis” cluster, which included hallucinations and delusions.

11 Hallucinations and delusions were rare in the present study, occurring in only 3% and 10% of patients, respectively, across the entire study period. However, it would be useful to further characterize psychotic symptoms in HD in a larger sample than in the present study, in terms of their overall prevalence, association with disease stage, and possible risk factors.

It is important to address potential limitations in the study. In the PBA-HD, the rater is required to score symptoms over the preceding 4-week period. The rationale for this is to increase accuracy in both patients' recall of feelings and events and the reliability of interviewers' rating of symptoms. We acknowledge, however, that this method has the potential to miss symptoms that have occurred between assessments but outside the 4-week period before the interview. A recently revised version of the PBA-HD overcomes this issue by documenting 1) the severity and frequency of symptoms within the preceding 4-week period; and 2) the severity at its worst since the last assessment. Nevertheless, the longitudinal prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms was consistently higher than baseline-point prevalence, suggesting that our data provide a more accurate picture of neuropsychiatric problems in HD than previous, cross-sectional reports. The issue of psychiatric medication also warrants consideration. As previously noted, the patients were attending a multidisciplinary clinic with specialist psychiatric input, where the instigation of psychiatric medication, when indicated, was routine. It is, therefore, likely that medication could have influenced the severity of affective symptoms such as depression and irritability. We cannot say for certain whether the overall pattern of symptom prevalence and progression would be the same in an entirely unmedicated cohort, nor would such a study be ethically defensible. Despite the high prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in HD, there have been very few symptom-treatment trials, with most reports in the literature being limited to single cases or small case-series.

30 Our findings highlight the need for symptomatic trials of psychiatric medication in HD in order to provide an evidence-base for the potential alleviation of distressing and disruptive symptoms in this condition.

To our knowledge, this observation represents the most comprehensive and lengthy longitudinal study of neuropsychiatric symptoms in HD. We have demonstrated that the longitudinal prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms is markedly higher than shown in cross-sectional studies of prevalence, suggesting that previous studies may have underestimated the extent of this clinical problem. The three main neuropsychiatric syndromes in HD—namely, apathy, irritability, and depression—were each associated with a distinct longitudinal profile, suggesting a different neurobiological substrate for each. Our data strongly support the notion that apathy, as a neuropsychiatric syndrome, is intrinsic to the evolution and progression of HD. Moreover, the PBA-HD Apathy subscale provides a sensitive measure of apathy that has the potential to be used as an end-point in clinical trials.