Decision-making involves collecting information about the expected valences, alternatives, and probabilities of available response options. Disruption to any of these component processes may result in risky behavior. The neurobiological circuitry underlying social decision-making includes such areas as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and insular cortex.

1 Patients with disruptions to the ventromedial cortex more frequently demonstrate impairments in social decision-making, in spite of otherwise largely-preserved intellectual abilities.

2,3 Tasks that measure social decision-making (i.e., weighing of risk and benefits) have demonstrated both selectivity and sensitivity to ventromedial-prefrontal cortex lesions. Poor performance on decision-making can persist despite relatively unimpaired performance on tasks of planning and problem-solving that reflect dorsal-lateral prefrontal functioning (e.g., the Wisconsin Card-Sorting test), suggesting different neuroanatomical circuitry that subsumes these related, yet dissociable, processes. One such instrument, the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), was developed in order to investigate the decision-making strategies in individuals with frontal lobe lesions. The task includes four decks of cards from which to choose, with each selected card resulting in either winning or losing a sum of “replica” money. Two out of the four decks will result in a net profit by the end of the task (i.e., Safe decks), whereas card selection from the other two will ultimately result in a loss (i.e., Risky decks). The decks that result in the net loss, however, offer larger payoffs early in the task than the others. Through its design, this task assesses participants’ capacity for decision-making and risk-taking by tracking which decks they draw from, thereby measuring their responses to reward/punishment and concern for future outcomes.

Decision-Making Among HIV+ Adults

The pattern of neuropsychological deficits typically observed in HIV+ individuals is consistent with frontal-striatal dysfunction (i.e., difficulties with attention and concentration, information-processing speed, motor functioning, and executive functioning).

4 There is also evidence that poor decision-making is prevalent among this population.

5,6 Where HIV can result in problems with decision-making, individuals who contract HIV tend to engage in greater risk-taking practices in general, which makes this population ideal for studying decision-making performance.

7 Hardy and colleagues

5 administered a modified version of the IGT to a group of HIV+ patients and seronegative control subjects. HIV+ patients performed worse on the gambling task than controls. Similarly, among substance-dependent HIV+ individuals, deficits have also been observed in decision-making.

6,8 Decision-making performance on the IGT moderated the relationship between emotional distress and reported sexual risk among HIV+ individuals, such that better performance on the IGT and greater distress predicted greater sexual risk-taking.

9 However, among individuals with worse IGT performance, there was no significant relationship between distress and reported sexual risk, suggesting that emotional distress in isolation does not play a critical role in poor IGT performance. In other words, intact neural circuitry subserving decision-making is critical in order for emotional distress to have an influence on the functioning of this neural circuitry, thereby increasing risk-taking behavior. Overall, results support the contention that HIV+ individuals are at risk for poor decision-making behavior.

Depression, Cognition, and Decision-Making

Depression is considered to be one of the neuropsychiatric features associated with HIV.

10,11 Although a number of studies have linked depression to impairments in executive functioning, attention, memory, and psychomotor speed,

12 such associations are not consistent, and many studies have failed to find direct associations between symptoms of depression and cognitive dysfunction.

13–15 Inconsistencies across studies may be due to methodological differences in how depression is diagnosed, measured, reported, or handled, with regard to severity.

16Nevertheless, what is consistent, and of particular interest to the current study, are findings supporting dysfunction in decision-making in depressed patients.

17 For instance, among depressed adolescents, Han and colleagues found impairments in both non-emotional areas of cognitive functioning (sustained attention and conflict-processing) as well as emotionally-laden domains (affective decision-making), with the latter being more associated with current mood state.

18 Furthermore, deficits in emotionally-charged decision-making tasks have also been observed in chronic pain patients with depression. There is considerable evidence that depression leads to biases in processing emotional information that can result in poorer performance on an affective Go/No-Go task.

19,20It is thought that depressed individuals are less likely to respond to negative feedback from the environment because of an decreased sensitivity to punishment,

21–24 difficulties in recognizing rewards,

22 or an inability to maintain reinforced behavior.

25,26 This, in turn, can result in poor performance on decision-making or learning tasks, particularly when the outcome is unclear or misleading.

27 Depressed patients may have difficulty with flexible decisions-making requiring them to change their response choices when a previously disadvantageous choice becomes advantageous, and vice versa.

17,28 Together, these studies suggest that depression may adversely affect social decision-making despite relatively intact cognition.

The extent to which cognition affects decision-making is only a small component of understanding the underlying processes involved in decision-making. Other variables linked to both cognition and decision-making may explain the process by which cognition actually influences decision-making. A variable may be termed a mediator “to the extent that it accounts for the relation[ship] between the predictor and the criterion.”

29 Although cognition and depression have been linked to poor decision-making, it is unclear whether mild disturbances in cognition (such as those typically reported by HIV+ patients) affects poor decision-making, or other variables, such as depression, modulate the relationship between the two constructs.

The purpose of the current investigation was to examine decision-making performance among HIV+ and HIV– individuals and to determine which cognitive and psychiatric features, if any, are associated with decision-making. It was expected that HIV+ individuals would demonstrate more poor decision-making choices than HIV– individuals. It was also expected that gambling task performance would be correlated with executive dysfunction and depressed mood. Finally, we expected depression to partially mediate the relationship between cognition and decision-making (as assessed by gambling performance).

Discussion

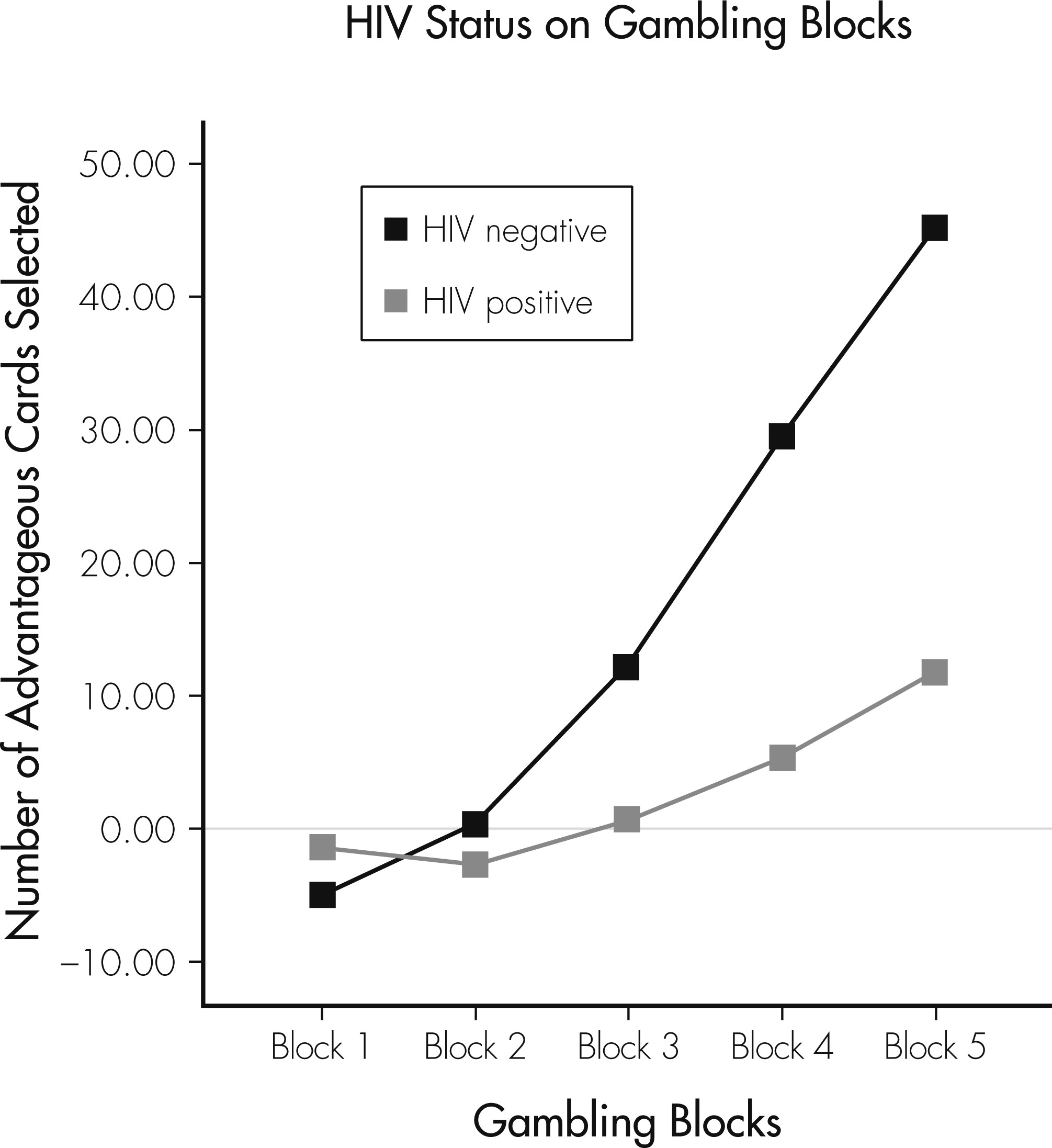

This study compared the impact of depression and cognition on decision-making in a cohort of HIV+ and HIV− adults. Using a learning index, we examined how various factors, such as HIV status, cognition, and depression, interfered with participants’ ability to learn on a decision-making task. Findings from this study extend the current literature by demonstrating the role of depression symptoms in decision-making and how emotional distress may result in problems in learning from rewards and punishments in spite of intact cognition. Consistent with findings in other studies,

5,8,36 HIV+ individuals demonstrated poorer neuropsychological functioning, including decision-making (assessed by a modified version of the Iowa Gambling Task), as compared with seronegative individuals.

Decision-making was associated with attention and executive functioning for the entire sample, which is consistent with several previous studies,

5,6 although not all.

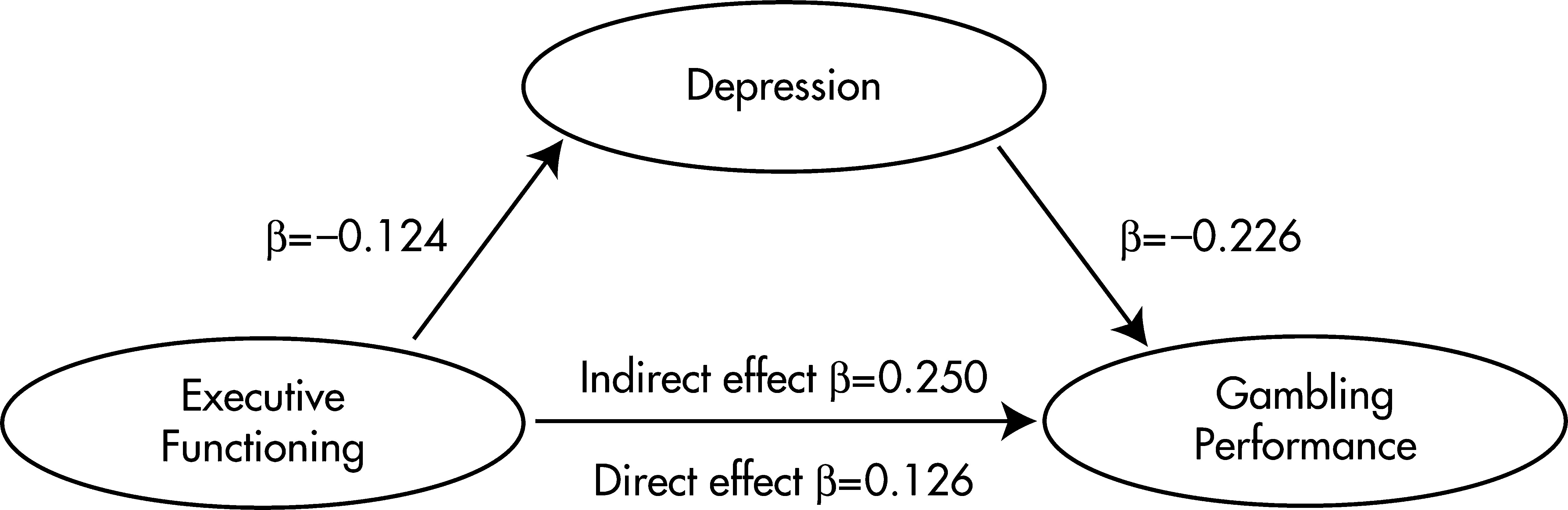

8,37 Further analysis into the relationship between discrete cognitive functions and gambling task performance demonstrated that executive functioning was most strongly associated with gambling performance, which is not particularly surprising, given that successful performance on the gambling task requires processes (i.e., flexible appraisals of the affective significance of stimuli, learning, and problem-solving) that are largely subserved by frontostriatal functions.

HIV+ individuals demonstrated higher levels of depression symptoms, which is consistent with other studies examining rates of depression among HIV+ and HIV– individuals.

11 Depression symptoms were strongly related to gambling-task performance, which is also consistent with Damasio’s somatic marker hypothesis, which asserts that emotional processes (anticipatory affective signals/somatic states) can guide or bias decision-making,

38 and with previous studies that have demonstrated that depressed individuals have decreased response to negative feedback.

23 In addition to decreased sensitivity, allocation of cognitive resources becomes reduced, which results in deficits in remembering and engaging in other effortful cognitive processes.

39 Thus, deficits become more evident in effortful tasks, rather than tasks that involve automatic processes, which may partially explain inconsistent findings related to depression and cognition.

Successful performance on the gambling task requires the generation of autonomic responses, signaling emotional identification of choices made and the rewards and penalties received as a consequence of choices.

3 Moreover, there is increasing evidence suggesting that depressed individuals appear biased in favor of high-risk/high-reward options.

40,41 Depression, in itself, involves poor flexibility in shifting behavior when reward conditions change, which supports the hypothesis that depression could involve a rigid, generalized strategy for responding to reward, regardless of changes in contingencies, and with models emphasizing that decreases in positive affect are a fundamental characteristic of depression and lack of response to rewards.

42It has been suggested that the gambling task measures different types of decisions. More specifically, there may be a differential influence of affective processes and executive functions, depending on whether decisions are made under ambiguity (e.g., first trials of the gambling task) or under risk (e.g., latter trials of task).

43,44 In the current investigation, learning differences due to HIV status, cognitive impairment, or depression symptoms did not emerge until the latter trials of the task, which is when participants are expected to distinguish between risky versus safe decks. It is of particular interest that depression partially mediated the relationship between decision-making and executive functioning, demonstrating the importance of depression symptoms to decision-making processes. Our partial mediation model supports the contention that that emotional distress, even at a subclinical level, may be associated with risk-taking among those with intact executive functioning.

9 Furthermore, our results demonstrate that affective disturbance has profound effects on decision-making. Engaging in risk-behaviors or decreases in sound judgment may be an early sign of depression. Practitioners working with HIV-infected individuals should to be sensitive to declines in judgment because these can signal depression, which can be aggressively treated through pharmacotherapy, evidenced-based psychotherapy, or a combination of the two methods.

We recognize that the current study design is limited with regard to addressing the “chicken/egg” problem; that is, whether depression associated with HIV status causes decision-making impairments on the gambling task, or whether individuals with HIV evidence premorbid difficulties with decision-making, which placed them at risk for infection and subsequent depressed mood. Our HIV+ participants were more likely to report past substance abuse, which suggests that this population may be more prone to engaging in risky behaviors in general. Furthermore, we were unable to target individuals with syndromic levels of depression (such as those diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder), as most of our participants’ BDI–II scores ranged from mild to moderate classifications of severity. Therefore, it is possible that relationships between executive dysfunction and depression may be, in part, influenced by mood severity. Moreover, alterations in reward choice and behavior may play a role in the continuity of depressive symptoms and, consequently, poor decision-making. Studies using a longitudinal investigation with a sample of individuals with clinically diagnosed major depression would be ideal to address this issue.

Although it could be argued that the observed relationships between cognition, depression, and decision-making are solely generalizable to the HIV+ population (because of the lack of significant findings in the HIV− population), we believe that the moderate effect sizes observed support their importance in decision-making for both subgroups. Although the relationships between these variables failed to reach statistical significance for the HIV− subgroup, this was largely due, in part, to small sample size (N=26). We recognize that a larger sample of controls would have been ideal, and that this is indeed a limitation to the current study. Nevertheless, despite this limitation, our findings are in accordance with the extant literature that has demonstrated that relationships between cognitive dysfunction and depressed mood affect performance on effortful cognitive tasks, and the findings extend previous work by demonstrating how dysphoric mood plays a partially mediating role in cognition and decision-making.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate the unique and shared affective and cognitive components involved in decision-making among a sample of HIV+ and HIV– individuals. This is particularly important for determining who is at risk for poor decision-making and, consequently, adverse outcomes. HIV+ individuals are more likely to report higher levels of depressed mood and to demonstrate cognitive problems, making this subgroup particularly vulnerable to showing poor decision-making. Given this, understanding which mechanisms are involved in decision-making can help to identify where breakdowns in the decision-making process may occur. Clinicians working with a high-risk population, such as the HIV+ population, should be aware that despite intact cognitive functioning, dysphoric mood can interfere with the ability to make sound judgments.