To the Editor: The Dandy-Walker malformation (DWM) is a congenital malformation characterized by the following triad: hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis, cystic dilatation of the fourth ventricle, and enlarged posterior fossa. The DWM, the Dandy-Walker variant (DWV) without enlargement of the posterior fossa, and the megacisterna magna are classified as a continuum of developmental anomalies termed as Dandy-Walker complex (DWC).

1 Clinical manifestations are dominated by neurological symptoms, developmental delays, and vegetative symptoms. Besides mental retardation, psychiatric symptoms are rarely mentioned in psychiatric literature. A few case reports describe bipolar/affective, psychotic, and attention-deficit disorders in DWM-patients.

2 However, whether psychiatric symptoms occur incidentally or are indeed integral to the syndrome, remains unclear. As recent literature supports a prominent role of the cerebellum in the organization of higher-order functions,

3 one might speculate about psychiatric symptoms as an integral feature. Here, we present a case of a DWV patient who was formerly diagnosed with comorbid intellectual disability, impulse-control problems, and attention-deficit disorder.

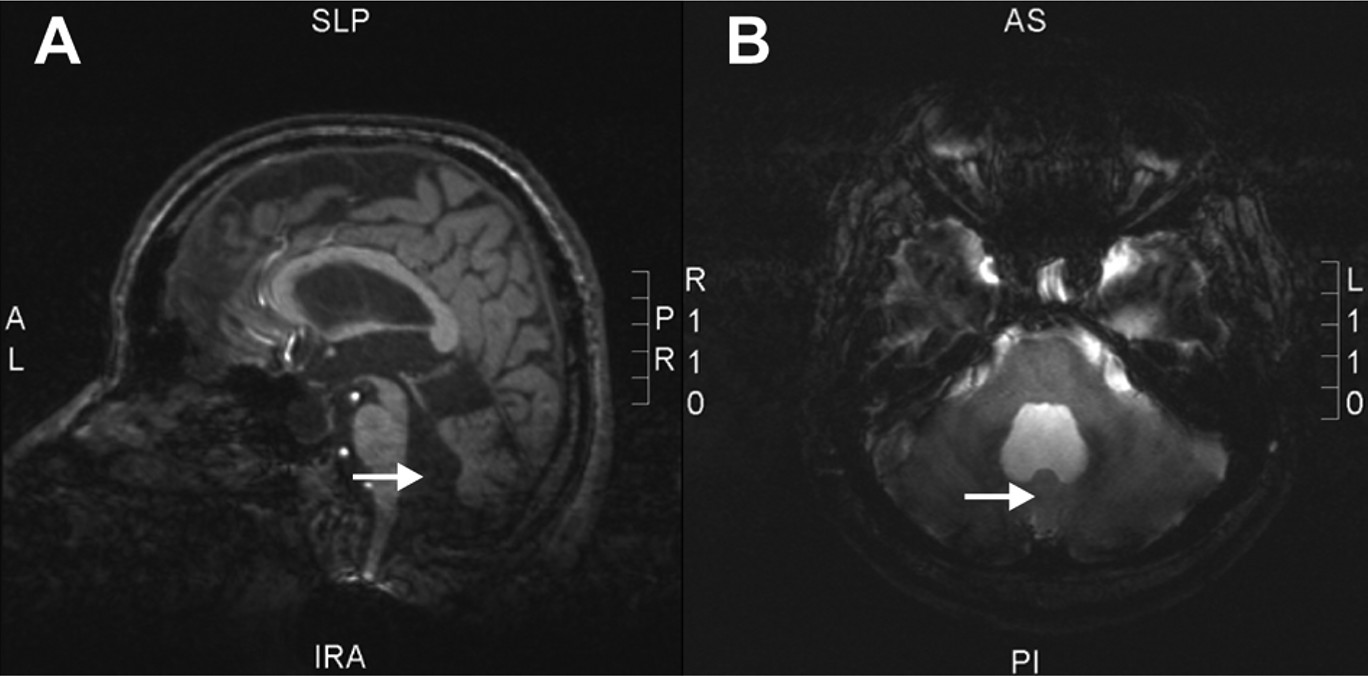

The 26-year old-male patient presented because of repeated conflicts with his parents. The parents reported delayed psychomotoric and verbal development, learning disabilities, as well as impulsiveness, since his early childhood when a DWV was diagnosed. Neuropsychological testing revealed an intelligence quotient of 89; attention deficits; a below-average performance in visual short-time, verbal, and working memory; and general impairments in executive functioning such as planning and problem-solving. The most recent admission of the patient was due to depressive mood, with blunted affect and psychomotor tension. He was highly distractable, and attention-deficits were evident. Physical examination revealed short stature and extremity ataxia. MR imaging confirmed a DWV (

Figure 1). Over 6 weeks of treatment, the most remarkable findings were unstable mood, inflexibility of thinking, difficulties in sustained attention, and impaired executive functioning such as lack of flexibility upon changing tasks; these did not improve with atomoxetine. Marked psychomotor agitation was observed in attention-demanding situations, and this improved with quetiapine.

Although these symptoms were previously linked to a psychiatric disorder (attention-deficit, intermittent explosive disorder), cerebellar dysfunction could well explain the symptoms as integral to the DWV. Recent evidence extends the role of the cerebellum beyond motor control.

4 Patients with cerebellar lesions exhibit cognitive deficits related to working memory, divided attention, planning, set-shifting, and abstract reasoning,

3,4 similar to the complaints of our patient. Summarizing a disturbance of cerebellar non-motor functions, Schmahmann et al.

4 described the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome (CCAS) characterized by impairments of executive functioning, distractibility, inattention, visual-spatial disorganization, personality change with blunting of affect, disinhibited behavior, and linguistic difficulties. These deficits are contributed to disrupted neural cerebellar-cortical circuits and have been observed in patients with cerebellar lesions of various origins.

4CCAS has not been described as characteristic to the DWV before, but its symptoms were clearly observed in our patient and largely overlap with all his psychiatric complaints. We suggest considering symptoms of CCAS as integral to the DWC and would like to draw attention to the CCAS that is largely underrepresented in the psychiatric literature.