To the Editor: Partial complex temporal epilepsy of adolescents and young adults is frequently due to hippocampal sclerosis. Partial complex temporal seizures are characterized by sudden onset and transient disorders of consciousness. In addition to disorders of consciousness, motor stereotypies, hallucinations (olfactory, gustatory, somatosensory, and auditory), delusions, and cognitive and affective signs can also be observed, making temporal lobe epilepsy one of the differential diagnoses of psychosis. However, temporal lobe epilepsy and psychosis are often comorbid conditions.

1 The neurosurgical treatment of epilepsy was developed in 1950 by Penfield, in Montreal, and then by Talairach and Bancaud, in Paris.

2 Amygdalohippocampectomy is performed in selected patients with refractory epilepsy.

3 The post-surgical results are generally very satisfactory in terms of seizure control, allowing discontinuation of pharmacotherapy in one-third of cases.

4 However, emotional disturbances, such as affective blunting,

5 may occur and are usually attributed to resection of limbic structures.

The characteristic diagnostic triad of neurological athymhormic syndrome includes variable combinations of disorders of affect, motor skills, and motivation.

7,8 Intellectual functions are preserved. In the athymhormy of adult brain injury, the nature of emotional feeling is intact, but expression of emotions is lacking, leading to “loss of self-activation.”

7 We describe the case of “Mr L.,” who presented a specific loss of emotional sensitivity; an emotional distress that does not correspond to that classically described in the literature in patients operated on for refractory epilepsy.

Case Report

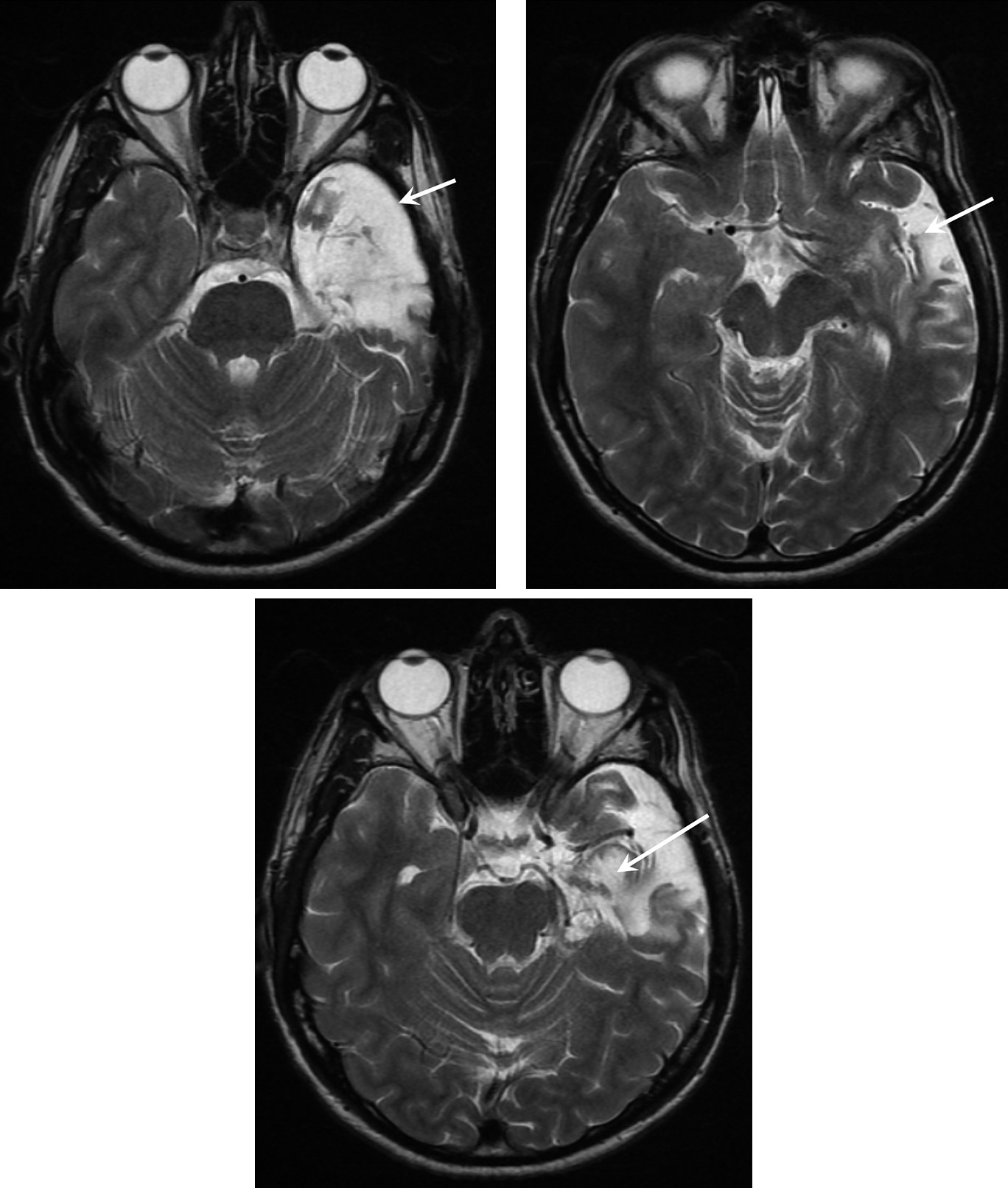

The patient developed febrile convulsions at the age of 2 years. After the death of his father (when he was 7), the young child developed behavioral changes that required placement in foster care until the age of 16. This antisocial behavior required prolonged antipsychotic treatment. He also experienced auditory hallucinations at the age of 13, but these productive symptoms were poorly defined and are not suggestive of preexisting psychotic illness. At the age of 22, he developed a first episode of delirium with wandering lasting about 45 minutes. A second episode occurred several days later and was associated with signs indicative of complex partial seizure, as it was associated with olfactory hallucinations, unresponsiveness with fixed gaze, and chewing movements for 2 minutes. Seizures persisted at a rate of 3–4/day; despite being given valproate (3 g/day), a secondary generalized seizure occurred, and gabapentin (2.4 g/day) was added. As seizures persisted, valproate (2 g/d) was added, in combination with vigabatrin (3 g/d) in 1996 and carbamazepine (600 mg/d) in 1996. Video EEG indicated a left temporal focus, and MRI showed left hippocampal sclerosis. At the age of 31, Mr L. underwent left amygdalohippocampectomy for the treatment of refractory temporal epilepsy (

Figure 1). After surgery, seizures were controlled without antiepileptic drugs. When he was referred for psychiatric examination, he reported a change of his emotional state: Mr. L appeared to be indifferent to the world around him and observed his emotional inertia. According to the patient, he felt that his reason was disconnected from emotional processes. The patient’s mother and doctor described marginalization since surgery: although he was able to maintain his sedentary job, he repeatedly requested a transfer. At the time of the assessment, he had no fixed address and no motor vehicle. He presented a fixed and durable mode of functioning. Mr L. described experiencing a “high” state since 2003, for which he was not responsible. Although his speech has become strange since the operation, he did not present any definite delusional features.

Complaining of having “lost all emotional feeling,” Mr. L consulted a psychiatrist in 2009, 6 years after surgery. This consultation provided a comprehensive review. Laboratory tests did not show any abnormality. Neuropsychological assessment of this right-handed patient with secondary school education was performed in the Amiens Memory Clinic. It showed normal general cognitive abilities (

Table 1), word-finding difficulties while other language modalities (repetition, comprehension, reading, writing) (Godefroy et al., 2003) were spared, and preservation of visual identification and visuoconstructive abilities. Episodic memory for verbal material was impaired, with a profile (preservation of immediate recall, impairment of recognition and recall without normalization following cueing) suggesting a genuine memory deficit related to a mediotemporal lesion (Godefroy et al., 2008). Executive functions were normal for both cognitive (i.e., tests) and behavioral components. Assessment of socio-emotional cognition was impaired, with impaired recognition of facial emotion (prominent for fear, disgust, and neutral emotions), empathy, and identification of inappropriate social behavior.

No preoperative psychiatric assessment was available for Mr L., but his preoperative history suggested that these subjective changes were “de novo.” However, the emotional “void” that he has experienced since surgery in 2003 does not correspond to any of the neurocognitive, psychosocial, and psychiatric complications described in the literature.

5,9–12Discussion

The patient’s family reported a “change of lifestyle” that occurred after neurosurgery. Eight years after the operation, Mr L.’s capacity to feel and express his emotions was significantly altered, but neither the investigations nor a detailed review of the complications described in the literature were able to provide a satisfactory diagnosis for his disorders (especially as there is no classification, at the present time, adapted to the description of neuropsychiatric symptoms

20).

There has been a growing interest in the psychiatric outcomes of patients undergoing epilepsy surgery in view of the high prevalence of presurgical psychiatric disorders and the potentially negative impact of surgery.

2,21 More than one-half of surgical patients with presurgical psychiatric disorders experience remission of symptoms after surgery.

2,21 According to Filho et al.,

21 “de novo” psychiatric disorders are detected in 9.6% of patients. In the same study, the presence of presurgical depression, presurgical interictal psychosis, and epileptiform discharges contralateral to the epileptogenic zone were risk factors associated with post-surgical psychiatric disorders. On the other hand, seizure freedom and improved psychosocial status predict remission of preoperative psychopathology.

22 However, Mr L. developed de-novo symptoms despite control of seizures.

How can the emotional changes experienced by this patient be described? Can a detailed analysis of his symptoms provide an answer?

Tamminga et al., in 1992, suggested involvement of the limbic system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

23 In a study published in 1999, Evangeli et al. established a correlation between the emotional disorders of schizophrenia and those related to a lesion of the amygdala.

24 These findings were confirmed by Fahim et al. in 2005, who proposed the hypothesis of a disorder of the connection between the amygdala and the frontal cortex to explain the emotional disorders observed in schizophrenia.

25 It therefore appears to be fairly well established that the brain of schizophrenia patients presents structural anomalies, mainly affecting the amygdala and hippocampus, the key structures of the limbic system.

Moreover, disorders of affectivity constitute the core deficit of schizophrenic illness and are formulated into several clinical concepts, as explained below. The gap between the expression, experience, and perception of feelings of schizophrenia patients was described as an “emotional paradox”

26 by Aleman and Kahn in 2005. Dulling of emotion (or reduction of emotional expression) resulting from of this “emotional paradox” is a key symptom of schizophrenia. Anhedonia, the neologism proposed by Ribot in 1896 to describe loss of sensitivity to pleasure,

27 can be considered to be a characteristic symptom of schizophrenia, at the border between emotional and mood disorders. Finally, the term ”psychiatric athymhormy,” which refers to weakening of the vital impulse and emotions, is used in psychiatry to characterize the psychopathological deficit of hebephrenia.

28However, the concept of anhedonia appears to be insufficient and inadequate to account for the emotional and affective “void” experienced by Mr. L. since the operation. The diagnosis of schizophrenia, according to the current definition of DSM-IV-TR,

29 cannot be proposed, but resection of the left cerebral amygdala would appear to be responsible for the patient’s symptoms.

As the neuropsychiatric concepts of anhedonia, psychiatric and neurological athymhormic syndrome, and dulling of emotions fail to describe our patient’s emotional state, we propose the term

emotional stoicism, by making an epistemological leap from neurological medicine to philosophy, as envisaged by Damasio.

30Mr. L. presented emotional impassiveness and serenity that resemble the descriptions proposed by the Stoic philosophers. This impassiveness and serenity also result from emotional insensitivity, acquired and directly related to the surgery performed in 2003. As amygdalohippocampectomy performed for the treatment of resistant epilepsy involves resection of the cerebral amygdala, we assume that emotional stoicism is a specific complication of this surgery. We propose the following diagnostic triad for emotional stoicism: the patient must have undergone amygdalohippocampectomy; must present clinical loss of emotional sensitivity (“apathy”); and must derive pleasure from his state of impassiveness (serenity).

By assuming that amygdalohippocampectomy induced a state of acquired emotional insensitivity (via disconnection of fronto-insular networks, actively involved in social-emotional disorders?), the case of Mr. L. resembles the emotional after-effects of lobotomy, performed until the middle of the 20th century for the treatment of schizophrenia and consisting of interruption of fronto-limbic nerve fibers.

31 Braslow described a marked reduction of emotional spontaneity: “it is as if he had lost his soul.”

32 Today, surgeons performing functional neurosurgery seek “to reduce the emotional experience of the symptoms.”

33 Lesions of the limbic system and emotional after-effects are strictly linked (anecdotally, but corresponding to anatomical-clinical correlations, Maguire et al., in 2000, showed that the volume of the hippocampus, a structure involved in spatial memory and navigation, is increased among taxi drivers, as compared with the general population

34).

Mr. L. received oral information from the neurosurgeon that specifically concerned the risk of neurocognitive after-effects. However, the information delivered to candidates for amygdalohippocampectomy should probably include the risk of loss of emotional sensitivity (although this complication is exceptional

35) and its psychosocial consequences. Preparation of a standard document designed to inform patients would facilitate standardized collection of informed-consent in neurosurgery. Finally, further studies are required to clarify the emotional status of post-surgery epileptic patients, and the clinical cases of patients treated by amygdalohippocampectomy could be considered in the light of this new approach.