Neuropsychiatric symptoms, in general, are particularly common in MS, with mood symptoms being the leading ones. In two case–control studies, neuropsychiatric symptoms were found in 80% and 95% of MS patients; delusions, in particular, were found in 3.5% and 7%, respectively.

1,2 Another two case–control studies found any DSM-IV Axis I disorder in two-thirds of MS patients; a psychotic disorder, in particular, was found in 0% and 2.7%, respectively.

3,4 A population-based study identified a rate of psychosis of 2%−3% in MS patients, as compared with 0.5%−1% in the general population.

5 Neuropsychiatric symptoms mainly occur during the evolution of MS. However, they have also been found among the disease’s initial manifestations, although this phenomenon is rather uncommon (0.2%−2.3%).

6 In a retrospective study among 682 MS patients, psychotic symptoms, in particular, were found in one-third of those cases where neuropsychiatric symptoms were among the initial manifestations of MS.

6Case Presentation

The case presented refers to a man with no previous personal or family psychiatric history. He was described as an introvert and not particularly sociable, but adequately cooperative and not particularly suspicious or eccentric. Epilepsy was the only disease mentioned in the medical history. He had his first epileptic seizure at the age of 21; antiepileptic medication (carbamazepine 600 mg daily) was initiated at the age of 36, after a grand mal episode.

At the age of 46, he was hospitalized in a general-hospital neurology department because of a cerebellar syndrome, suggesting a cerebrovascular ischemic attack or MS. He manifested an episode of dizziness, nausea, walking instability, and headache for 2 days before his admission. The neurological clinical examination revealed hemianopsia (right), unilateral paresis of VII (right), and a unilateral (right) pyramidal symptomatology. Brain MRI revealed multiple hyperintensities in the subcortical white matter, the semioval centers, the periventricular white matter, particularly on the left, and the left hippocampus. Differential diagnosis included MS and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). The lumbar puncture revealed 10 cells, 20% proteins and 60% sugar, and an oligoclonic band of IgG in the cerebrospinal fluid. The patient was treated with acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg and carbamazepine 800 mg daily.

Thereupon, psychiatric symptomatology emerged. Immediately after his release from the hospital, his relatives noticed that he began to “behave strangely.” He was anxious, irritable, seemed depressed, and often burst into tears. He expressed the fear of being abandoned, considering himself as handicapped. He also manifested outbursts of anger toward his wife, accusing her of being unfaithful to him. Under his delusional belief that his wife had a boyfriend, he used to wake up at night crying and looking for him. He had no insight on his beliefs. Eventually, under his relatives’ pressure, he was persuaded to visit a psychiatrist and was given antipsychotic medication (risperidone 3 mg daily at first, later combined with quetiapine 150 mg daily), but with no significant improvement.

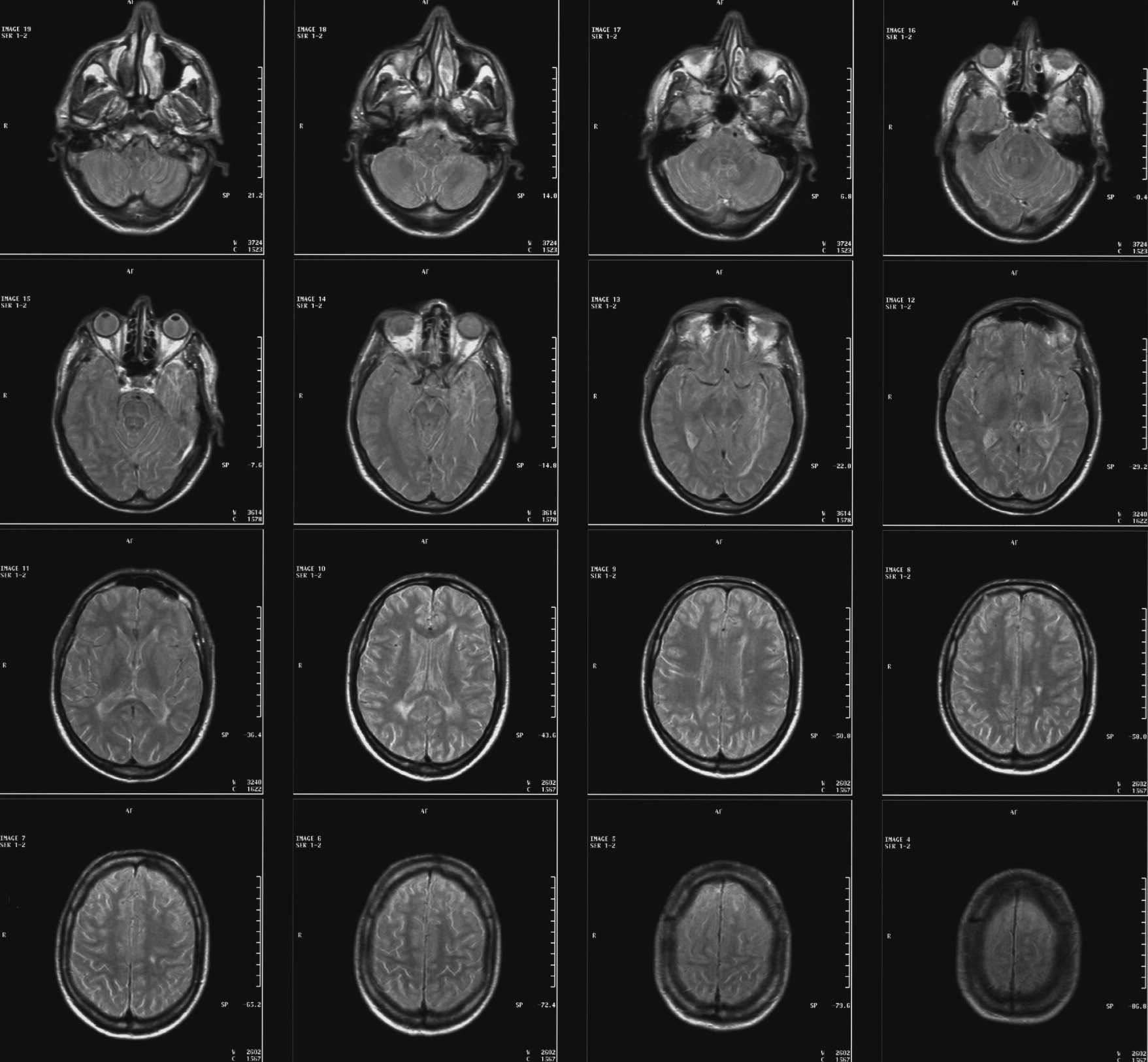

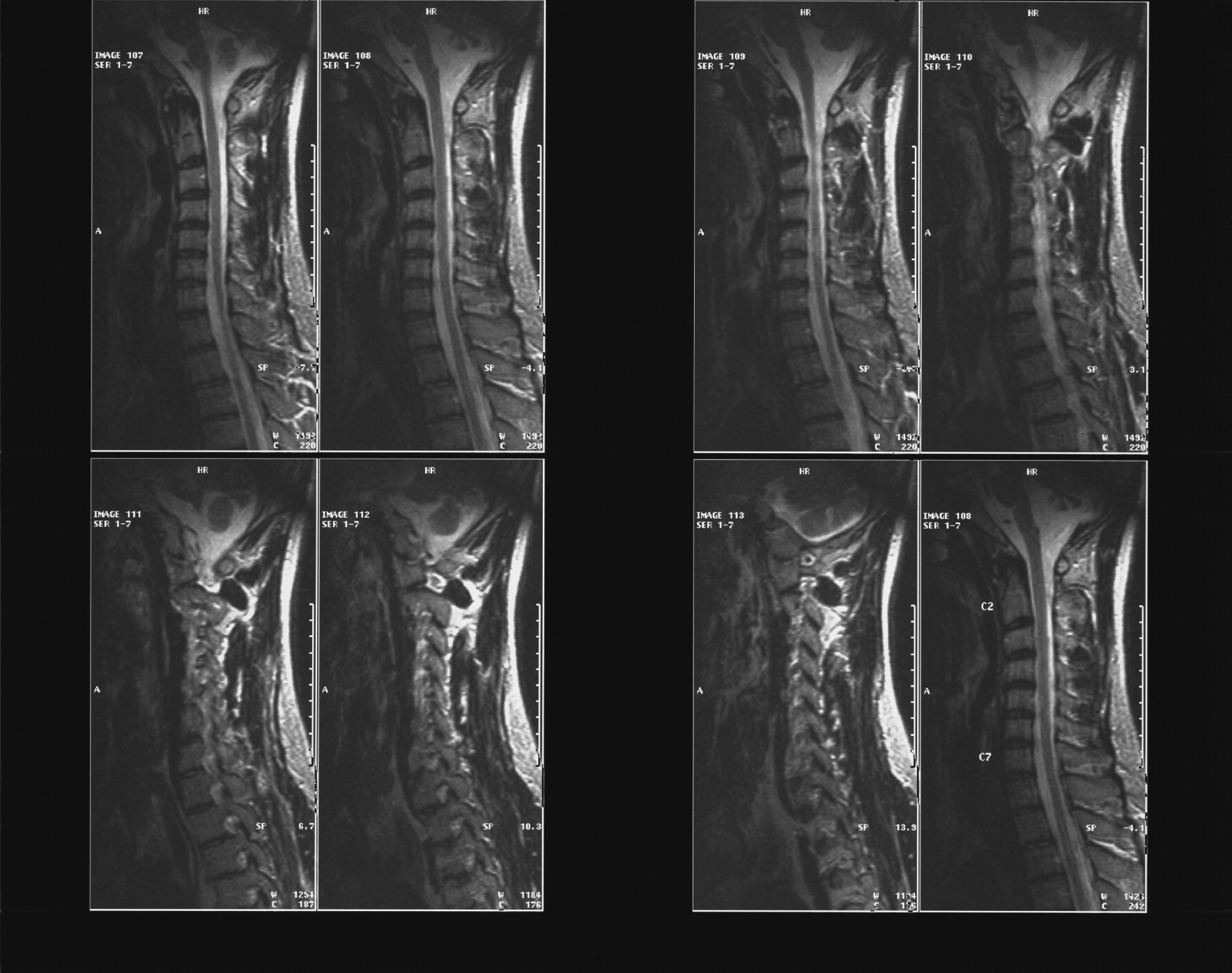

At the age of 48, he was hospitalized again, because of walking disturbances. The neurological clinical examination revealed a bilateral pyramidal and unilateral (right) cerebellar symptomatology. Brain MRI revealed MS-consistent abnormalities in both the brain and the cervical spine, as well as cerebellar and left temporal atrophy (

Figure 1,

Figure 2). As for the evoked potentials, a bilateral prolongation of the somatosensory evoked potential P38 was found. The diagnosis of MS was finally established, and the patient was released on glatiramer acetate 20 mg, amantadine 200 mg, carbamazepine 800 mg, risperidone 3 mg, quetiapine 150 mg, lorazepam 1 mg, acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg, and calcium folinate 15 mg, daily.

Since the patient’s psychiatric symptomatology remained unremitted, he was referred to and admitted in our general-hospital psychiatric department 1 year later, that is, at the age of 49. On admission, he demonstrated a mild psychomotor retardation and mildly depressed mood. He himself attributed his symptoms to his movement difficulties, but they might also be associated with his expressed feeling of being handicapped, the fear of being abandoned, and the delusional belief that his wife was being unfaithful to him. However, during the psychiatric interviews, he never admitted having such thoughts and implied that everything was “OK.” According to his relatives’ descriptions, his beliefs were strong, limited to and organized around this particular theme of infidelity. He showed no insight at all. The only symptom he complained about was the movement difficulties he met, although he often tended to underestimate both the symptoms and the severity of his neurological disorder. He occasionally demonstrated shallow affect, incongruent with the conversation context. No hallucinations were ever reported, neither by the patient nor by his relatives, and no clinical implication for their existence ever emerged. The findings from the neuropsychological examinations performed were consistent with an organic brain disorder (Trail-Making Test [TMT] A: 168 seconds, impaired shape-drawing, for example, coil: 1/3, rhombus: 0/3, cube: 2/3, house: 1/3.) No further psychometric tests were performed, since Greek was not the patient’s native language. The EEG revealed no focal or diffuse abnormalities.

Concerning treatment, risperidone was withdrawn, and paliperidone 6 mg daily was initiated. Gradually, quetiapine was tapered and withdrawn also, and paliperidone was raised to 12 mg daily. However, the patient showed no significant improvement. Clozapine was not indicated because of the history of epilepsy. Thus, we proceeded with the addition of haloperidol 5 mg, cautiously raised up to 20 mg daily. Thereupon, the patient demonstrated an improvement for the first time, as far the delusional ideas and the related behavior were concerned. A few days later, he manifested a blank staring spell—probably an absence seizure. The neurological clinical examination and CT performed revealed no recent abnormality. In the following days, he demonstrated a further improvement after haloperidol had been increased to 30 mg daily. No extrapyramidal signs ever emerged. Finally, he was released—after 45 days of hospitalization—with a complete recovery from his psychotic symptoms, although he had not achieved full insight. His relatives also confirmed his improvement. His medication consisted of haloperidol 30 mg, paliperidone 12 mg, lorazepam 5 mg, viperiden 4 mg, carbamazepine 800 mg, glatiramer acetate 20 mg, and calcium folinate 15 mg daily.