Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) results in emotional blunting and low levels of emotional arousal (

1,

2). This disorder commonly affects mesiolimbic frontal, anterior temporal, and anterior insular brain regions involved in emotional processing (

3–

7), and hypoemotionality underlies apathy and many of the other socioemotional characteristics of bvFTD (

5). Dysfunction of emotional reactivity and responsiveness can significantly contribute to empathic disengagement and impaired interpersonal reciprocity in bvFTD (

8,

9).

Loss of empathy is an important clinical diagnostic criterion for bvFTD and could result from an overall emotional blunting (

5). Empathy, or the identification (ability to understand and resonate) with the emotional experience of others (

10), is a complex construct that includes both cognitive components, such as perspective taking, and affective components, such as affect sharing (

11–

13). Previous studies of bvFTD have found deficits in cognitive empathy (

14), emotional empathy (

8,

15–

17), and both (

18–

22). Affect sharing includes emotional contagion, variously defined as a rapid and automatic synchronization of emotional and physiological states with another person (

11,

23). Prior research in bvFTD suggests that patients with bvFTD are psychophysiologically hyporesponsive, and hence generally impaired in responding to emotion stimuli (

24). This emotional blunting could be primarily responsible for the loss of empathy in bvFTD.

Another possibility, however, given the prominence of empathic behavioral impairments in bvFTD, is that patients with the disorder have specific problems in emotional empathy or emotional contagion not simply due to general emotional hyporeactivity. This is further supported by the locus of neuropathology in bvFTD, with involvement of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insula, and right anterior temporal lobe (

25–

28), structures that particularly mediate empathic behavior. In lesions studies, emotional contagion was shown to be impaired by lesions in a predominately right-sided network involving inferior frontal and orbitofrontal regions, as well as the amygdala, temporal pole, anterior insula, and ACC plus involvement of the uncinate fasciculus (

15,

17,

29).

The presence of a specific deficit in emotional contagion rather than a generalized emotional hyporeactivity may be distinguishable with psychophysiological measures. Skin conductance responses (SCR) are a measure of autonomic activity that can reflect specific impairment in emotional empathy or general emotional hypoarousal (

24). In bvFTD and traumatic brain injury, decreased SCR have corresponded with reduced emotional reactivity to low-level emotional arousal (

24,

30) and to complex high-level emotional empathy (

31,

32), and elevated SCR have corresponded with affective mentalization (

33). Studies using stimuli designed to evoke empathy (empathy stimuli) have tended to focus on emotional aspects rather than a specific empathic nature of the stimulus responses (

34,

35). Yet there may be differential psychophysiological responses to empathy stimuli irrespective of general emotional responsiveness. Hence, studies of empathic responsiveness need to assess responsivity to both empathy stimuli and stimuli designed to evoke emotion in general (emotion stimuli).

This study investigates whether impaired empathy in bvFTD is a specific behavioral deficit that is not just due to general hypoemotionality or impaired emotional arousal. Because patients with bvFTD have decreased insight and self-awareness, we used alternate measures of empathy. Informant-based behavior scale and SCR measures of empathy are compared while controlling for behavior scale and SCR measures of general emotional blunting among patients with bvFTD compared with patients with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The purpose of the age-matched Alzheimer’s disease comparison group was to control for general effects of cognitive impairments on the outcome measures. The SCR psychophysiology additionally requires the inclusion of healthy control (HC) subjects. We hypothesized that there would be a disproportionate impairment in reactivity to empathy stimuli in the bvFTD group compared with the Alzheimer’s disease and HC groups.

Results

No significant differences were observed on age at examination, sex, ethnicity, and years of education across the three study groups. All of the patients in the bvFTD group had a history of decreased empathic behavior compared with none of the participants in the Alzheimer’s and HC groups. As expected, both dementia groups had lower MMSE scores compared with the HC group, and the bvFTD group had significantly higher empathic function (SDS) and emotional blunting (SEB) scores compared with the Alzheimer’s disease group (

Table 2). The worse SDS scores for the bvFTD patients remained even after adjusting for SEB scores (F=15.04, df=2, 23, p<0.001). In an additional comparison with historical data from age-matched normal control subjects, bvFTD patients performed significantly worse on the SDS (t=4.2, p=0.0004) but not Alzheimer’s patients, and both patient groups performed significantly worse on the SEB (p<0.001) (t=58.24 and t=61.95, respectively).

Psychophysiological Results

The mean logSCR differed significantly between the bvFTD (0.324 [SD=0.205]), Alzheimer’s (0.542 [SD=0.174]), and HC(0.405 [SD=0.207]) groups across all the IAPS picture stimuli (F=607.85, df=2, 15, p<0.001), with post hoc (least significant difference, Tukey’s b) of the bvFTD group compared with the Alzheimer’s disease group (p<0.001), the bvFTD group compared with the HC group (p<0.01), and the Alzheimer’s disease group compared with the HC group (p<0.001). For all conditions, the mean logSCR was lowest for the bvFTD patients compared with Alzheimer’s patients and HCs (Alzheimer’s patients showed a higher mean logSCR compared with the other two groups). There were no significant group differences based on the four types of stimuli. When emotion (high emotion, low emotion) was added as a covariate, the group differences remained unchanged (F=405.18, df=2, 15, p<0.001), with the same post hoc differences for empathy pictures (i.e., lowest scores for the bvFTD group).

Neuroimaging

On analysis of FreeSurfer extracted ROIs, there were significant group differences between the two dementia groups when using bilateral averages of the left and right ROIs (total of 20 comparisons). The bvFTD group had significantly decreased mean volumes in four ROI measures referable to the frontal lobes (overall frontal volume, pars orbitalis, caudal anterior cingulate, and lateral orbitofrontal) compared with the Alzheimer’s group. In contrast, the Alzheimer’s group had decreased volumes in parietal (inferior, superior, supramarginal, and precuneus) and inferior temporal ROIs compared with the bvFTD group.

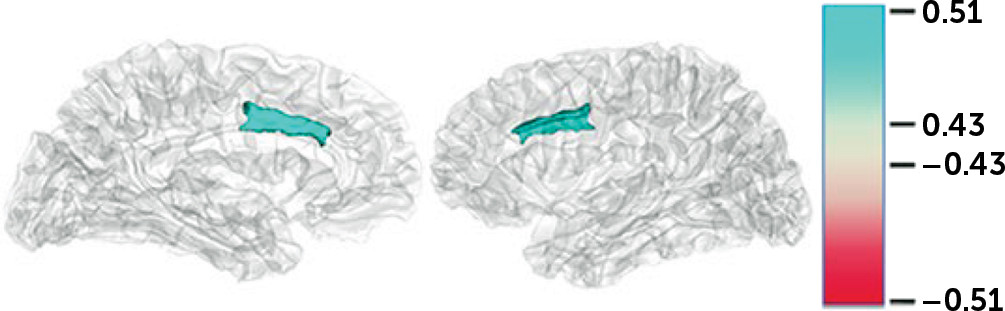

Additional correlations were performed between the logSCR scores for each of the four stimulus categories and the ROI volume measures (

Figure 1). There were no significant correlations within groups except when examined across both dementia groups using a significance level of p and q*<0.01. For the logSCR results, there were significant correlations between both empathy and high emotion and the gray volume of the left >right dorsal ACC (0.517 and 0.512, respectively) (

Figure 1).

Discussion

Among patients with bvFTD, this study showed decreased emotional empathy beyond the extent of hypoemotionality characteristic of bvFTD. The bvFTD patients had decreased empathy behavioral scale scores, regardless of performance on an emotional blunting scale, and the bvFTD patients had decreased SC changes to empathy stimuli that persisted after adjusting for responses to emotion stimuli. These findings indicate that patients with bvFTD are disproportionately impaired in empathy compared with general emotion stimuli. Moreover, across groups, the correlation of SCR to empathy and emotion stimuli with the volume of the dACC suggests a role for this area in emotional empathy.

BvFTD is an example of disease that targets the empathic behavioral centers of the brain (

45). Patients with this disorder present with alterations in empathic behavior ranging from disengagement and lack of consideration for others to sociopathic acts with a loss of the emotional aspects of morality (

5,

46,

47). From a neuroanatomical point of view, bvFTD is clearly centered in areas critical to the “empathic brain,” such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, ACC, anterior insula, amygdale, and right anterior temporal lobe (

48). These areas are part of neural networks dedicated to empathic functioning and self-awareness, particularly the salience network centered in the ACC and frontoinsular regions (

49).

A major consideration is whether loss of emotional empathy in bvFTD results for a generalized autonomic hyporesponsiveness to emotion or whether there is a specific impairment in the emotional contagion aspect of empathy. In addition to behavioral scales, psychophysiological measures are particularly useful for differentiating the effects of empathy from general emotional reactivity. In this study, the SCR among the bvFTD patients remained low to empathy stimuli, regardless of responses to emotion stimuli. An incidental finding in this psychophysiological study is that the Alzheimer’s patients had higher SCR consistent with reported high baseline anxiety among early-onset patients with Alzheimer’s disease and neurodegeneration of temporal lobe structures involved in emotion detection and inhibition (

23,

50,

51).

Some investigators have reported an increased overall threshold for psychophysiological responsiveness among patients with bvFTD (

52), implying decreased resting sympathetic tone, and a higher threshold for emotional reactivity in general (

53). The bvFTD patients did have emotional blunting and an impaired reactivity to emotion stimuli. The results of this study, however, suggest the presence of decreased emotional empathy beyond the presence of generalized emotional blunting, as control for emotion on the behavioral scales and psychophysiology did not eliminate measures of decreased empathy, and the psychophysiological responses to empathy and to emotion were also dissociable.

On neuroimaging, the ACC is implicated in empathizing or vicariously processing another’s rewards (

54,

55); it may be abnormal in psychopathy and autism (

56–

60). In this study, the SCR to both empathic and emotion stimuli were strongly correlated with the neuroimaging volume in the dACC, suggesting that this area contributes to emotional empathy through emotional appraisal. Traditionally, investigators have divided the ACC into a cognitive region in the dACC involved in error detection and executive tasks and an emotion-related region in the rostral-ventral ACC involved in assessing and regulating emotion (

61). However, recent literature has indicated that the dACC, particularly in its anterior section, evaluates whether stimuli are sufficiently motivationally significant to induce an emotional reaction (

62). This general emotional appraisal role relates to emotional empathy when the ACC distinguishes whether the stimuli affect others rather than oneself (

63–

66). Empathy involves a vicarious reward prediction that depends on the ability to predict when others are likely to receive rewards (

56). Studies indicate that a subregion of the ACC in the gyrus (ACCg) processes and signals anticipated rewards for other people, as well as for oneself (

67–

71). The ACCg is significantly positively associated with trait emotion contagion and trait empathy (

56).

This preliminary study had several important limitations. First, the number of participants was relatively small. This particularly affected the strength of the neuroimaging findings; the only significant findings evident on across-groups correlations used a liberal significance level. The participant numbers, however, were sufficient to reveal significant and insightful differences between the groups on the behavioral scales and psychophysiology measures. Second, this study corroborates reports of a high degree of anxiety and heightened emotional contagion in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease (

23,

50,

51). However, this does not alter the main finding of this study, that worse empathy among the bvFTD patients is not explained by emotional blunting. Third, there are limitations in the informant behavior ratings, as the SDS does not clearly distinguish cognitive and emotional aspects of empathy and the SEB has some overlap with emotional empathy. Fourth, the behavioral scales and neuroimaging analysis did not include HC, where there is normative data. Finally, the study was limited by focusing on empathic versus emotion stimuli without further analysis of valence (positivity/negativity of the emotion) or of other specific emotions, such as disgust sensitivity.

In conclusion, the present study highlights decreased responsiveness to empathy stimuli among patients with bvFTD, a disorder that starts and focuses in frontotemporal areas of the empathic brain. A comparison with patients with Alzheimer’s disease suggests that there is disproportionate impairment in reactivity to empathy stimuli among those with bvFTD not due to their general autonomic hyporesponsiveness. This report is a first, preliminary exploration, and future studies are planned in order to expand and further evaluate these observations in a greater number of patients with bvFTD.