To avoid the potentially relevant overlap of delirium and catatonic features (

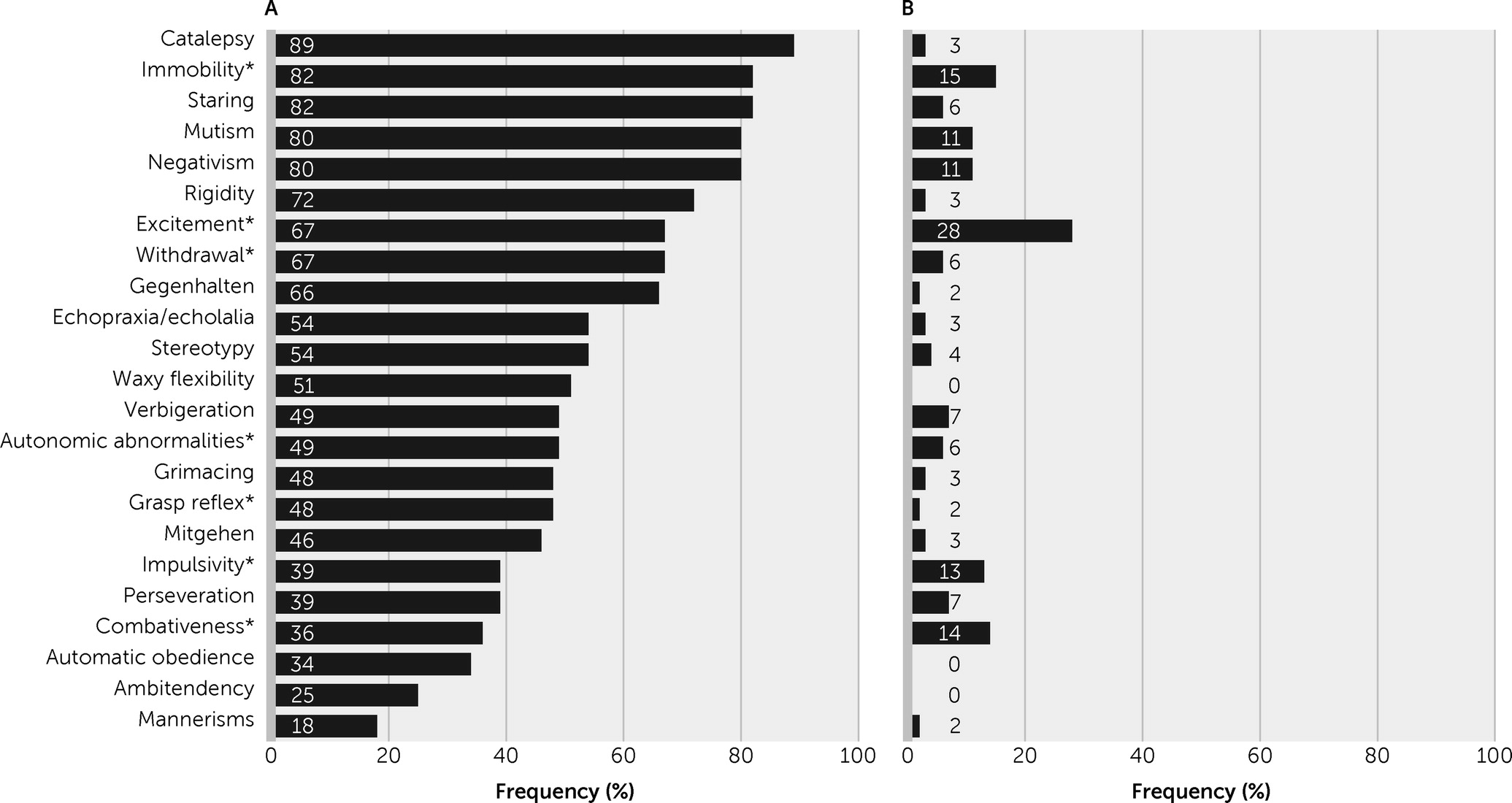

4), we used a case definition that excluded agitation-excitement, immobility-stupor, and withdrawal. From a clinical point of view, several catatonic signs that are not part of the standard construct of delirium (i.e., waxy flexibility, grimacing, stereotypies, mannerisms,

gegenhalten,

mitgehen) are particularly useful for this distinction. The findings of the present study support the hypothesis that recognizing catatonic delirium may be clinically useful from an etiological perspective and that the mutual exclusivity of delirium and catatonia in DSM-5 requires review and possible reconsideration. Several questions arise and may be helpful in the discussion of both this study’s results and the previous evidence.

Is It Possible to Differentiate Between Delirium Motor Subtypes and Catatonic Delirium?

Both delirium and catatonia exhibit motoric variants (

4), so one of the essential questions when considering their co-occurrence is the fact that certain signs may overlap (i.e., they are not specific to either syndrome). Francis and Lopez-Canino proposed that catatonia may account for the motor components of hypoactive delirium (

32). Similarly, Grover et al. (

3) demonstrated an association between catatonic signs and hypoactive delirium. However, these perspectives on catatonia may overemphasize its motorically hypoactive-stuporous features and ignore the existence of excited catatonia (delirious mania) (

33). In a retrospective chart review, Llesuy et al. (

34) noted that the presence of agitation increased the likelihood of underdiagnosis of catatonia in general hospitals. More important, fluctuations in psychomotor activity are often seen in both delirium and catatonia (

4).

After multivariate analysis, our findings do not support the hypothesis that catatonic delirium is explained by, or fully accounted for by, hypoactive delirium. Catatonic delirium was also observed among patients with hyperactive delirium and mixed delirium. Because this was a referral population, delirious patients who tended to be hypoactive may have been underrepresented in this sample because they are less disruptive and therefore less likely to be referred for care at our institution.

Does Comorbid Catatonia Have Significance for Etiology, Pathophysiology, Prognosis, or Therapeutics Among Patients With Delirium?

Our study revealed a significant association of catatonic delirium with two neurological diagnoses: viral encephalitis and anti-

N-methyl-

d-aspartate receptor encephalitis. This finding is consistent with recent studies that have highlighted the importance of catatonia in the recognition of patients with this form of autoimmune disease (

20,

35). An important link has been observed between catatonic syndrome and immunological mechanisms and conditions (

36). However, delirium in patients with anti-

N-methyl-

d-aspartate receptor encephalitis has received little attention and is probably underestimated (

37).

Seizures are a common manifestation of anti-

N-methyl-

d-aspartate receptor encephalitis, occurring among approximately 70%−80% of cases (

38), so the high proportion of these patients in our study may also raise the question of whether features of catatonic delirium were the product of epileptic activity, because postictal states and nonconvulsive status epilepticus have been reported as a cause of catatonic features (

39). This issue deserves further research.

Our sample is limited to neurological patients, and thus it must be complemented by studies in general hospitals, geriatric and pediatric settings, and psychiatric wards. One would expect that the clinical phenomenon we describe is not common in general hospitals. Australian and Spanish studies with samples of geriatric patients described catatonia as present in 5.5%−6.3% of the cases being referred to consultation-liaison psychiatry services; the diagnosis was associated with neurological and psychiatric preexisting diagnoses, metabolic conditions, and multifactorial etiologies; some patients presented with additional features of delirium (

40,

41). A study from a general hospital in the United States described 54 cases of catatonia and reported that the attribution of catatonia to a psychiatric etiology was associated with significantly less diagnostic workup. In contrast, clinical suspicion of comorbid delirium (in 53% of the cases) was a strong predictor of a more thorough general medical workup, leading to the recognition of sepsis, hyponatremia, lithium toxicity, and renal failure as causes of encephalopathy (

42).

In our study, 23.1% of the patients with delirium had four or more catatonic signs, fulfilling our definition of catatonic delirium. In previous studies, the prevalence of catatonia among patients with delirium has been higher. A sample of critically ill patients (N=136) showed a 30% rate of catatonic delirium, and the most significant proportion of those patients had sepsis and acute respiratory distress (

2). With a larger sample in a general hospital (N=205), Grover et al. (

3) found that catatonia was present among 12.7%–32% of patients with delirium, depending on the diagnostic approach (DSM-5 or BFCRS). Unfortunately, they did not report the medical diagnosis of patients with catatonia and delirium. It is important to consider the possible overestimation of the frequency of the comorbid condition due to nonspecific symptom overlap when a low threshold is used for catatonia diagnosis with the BFCRS.

Diagnosing catatonic signs among patients with delirium has repercussions not only related to the underlying medical conditions but also when symptomatic treatment is necessary (

4). The antipsychotics often used to manage agitation during hyperactive delirium can precipitate neuroleptic malignant syndrome in patients with catatonia (

43). Benzodiazepines, the first-line treatment for catatonia (

44), are known to be deliriogenic, worsening symptoms and lengthening hospital stay among patients with delirium (

43). Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is considered the most effective treatment for catatonia, even after pharmacotherapy with benzodiazepines has failed (

45). However, ECT is not recommended in the management of delirium (

43), and this issue continues to be understudied.

In our sample, the presence of catatonic delirium was associated with a longer hospital stay, a more prolonged delirium, a higher incidence of seizures, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. This severe complication or different forms of antipsychotic intolerance have been reported among patients with anti-

N-methyl-

d-aspartate receptor encephalitis (

35,

46) and also among patients with delirium and catatonia arising from other conditions (

41). One would therefore use antipsychotic drugs with great caution among patients with delirium who also have catatonic features.

Regarding the pathophysiological aspects of the comorbid conditions, to our knowledge, no functional neuroimaging studies have addressed patients with coexisting delirium and catatonia. However, although the evidence is still scarce, abnormalities of brain resting-state functional connectivity have been found for both syndromes (

47,

48). Delirium has been associated with changes in the default mode network, the salience network, and the frontoparietal control network, which would lead to the altered level of consciousness, reduced awareness of the environment, inattention, and impaired reality testing that facilitates delusions and hallucinations (

49). However, in a recent functional MRI study by Parekh et al. (

50), patients with catatonia showed reduced connectivity in sensorimotor, salience, frontoparietal, and cerebellar networks. Even though a global disruption of the brain network may be present in both delirium and catatonia, further studies are necessary to reveal whether these neuropsychiatric syndromes share common abnormalities in the functioning of brain networks.