Although functional neurological symptom disorder (FNSD) is a common diagnosis in neurology (

1), optimal management of this disorder remains uncertain. Psychotherapy is recommended, but its effectiveness is undetermined. In a meta-analysis of psychological interventions for dissociative seizures (a common subtype of FNSD), investigators found that 47% of patients were seizure-free after treatment (

2); however, most studies involved <50 participants (

3). To our knowledge, the Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Adults With Dissociative Seizures (CODES) trial comprising more than 360 participants is the only fully powered study (

4). This randomized controlled trial assessed the addition of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to standardized medical care for patients with dissociative seizures. While the study showed no additional improvement with CBT on seizure frequency, improvements were seen across several secondary outcomes.

Although a subgroup of patients with FNSD report no previous traumatization (

5–

7), the association between FNSD and trauma is widely recognized, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common comorbid condition (

8). However, there has been little exploration of the effect of psychotherapy on PTSD symptoms in the context of FNSD. Given that psychological interventions may address excessive avoidance and alexithymia and may involve the processing of traumatic memories, psychological interventions could, conceivably, aggravate PTSD symptoms.

In this study, we explored psychotherapy-related changes in PTSD, anxiety, depressive, and somatic symptoms, as well as changes in health-related quality of life, among patients with FNSD. We hypothesized that there would be observable reductions in symptom burden and increases in health-related quality of life among patients with FNSD undergoing psychotherapy.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Data were collected between November 2015 and March 2019 in the context of a service evaluation capturing responses from consecutive patients referred to a team of seven psychotherapists working in the Department of Neurology at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, United Kingdom. Referrals to psychotherapy were made by consultant neurologists serving a regional population of 1.39 million people (

6). Patients completed questionnaire packets after referral for psychotherapy. Posttherapy questionnaires were sent out before the final session and returned by postal mail. The baseline data used here overlaps with previously reported data (

6). Ethical approval was received by the University of Sheffield ethics board. All patients consented to their data being used for research purposes.

Self-reported questionnaire data were complemented by clinical information from hospital administration systems. For some analyses, FNSD symptoms were divided into two subtypes: dissociative seizures and other FNSD. Patients with dissociative seizures and additional FNSD symptoms were included in the dissociative seizure subgroup. No patients with mixed neurological and functional disorders (for example, patients with mixed epilepsy and dissociative seizures) were included in the study. Other FNSD symptoms included weakness; abnormal movement; dysphagia; speech problems; sensory loss; and visual, olfactory, or hearing disturbances. Most patients had several symptoms.

Psychotherapeutic Intervention

Patients accessing psychotherapy were initially assessed during an hour-long interview. Patients who met criteria for inclusion were offered a maximum of 20 additional sessions (each lasting 50 minutes). Although symptomatic improvement was considered a key goal of therapy, especially among those with evidence of PTSD, improvements in quality of life were considered equally important.

The psychotherapists had training and experience in a variety of modalities. However, the team’s integrative therapeutic model is informed by both a shared understanding of the etiology of FNSD within the wider neurology context and an applied integration of evidence-based elements of psychotherapeutic theory and practice. Given this therapeutic model, patients were randomly allocated to therapists upon reaching the top of the waiting list.

At the formulation stage of evaluation and treatment, therapists considered the role of adverse experiences, including PTSD, as predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating the patient’s functional symptoms. This shaped the focus of the therapy, which was informed by theories of human development and personality, particularly attachment theory (

9), and often involved trauma-focused therapeutic approaches, such as those developed by Ogden and Fisher (

10), Pace (

11), and Rothschild (

12). Because FNSD represents the interplay of physical, emotional, and cognitive dysfunction, the psychotherapeutic approach employed by our team combined features of somatic-focused work, emotional processing, and cognitive restructuring. This was enabled through the development of a strong therapeutic collaboration, with core relational conditions at the center (

13).

Outcome Measures

Demographic characteristics.

Patients’ age, gender, marital status, and employment status were self-reported. Relationship status was categorized as living with or without a partner. Employment status was categorized as “economically active” or not; patients were categorized as economically inactive if they were unemployed, in receipt of disability benefits, or retired. Information on cultural, ethnic or racial background and social class was not routinely collected as part of this study, but the Department of Neurology at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital was a major contributor to the CODES study, which demonstrated that members of lower socioeconomic groups were overrepresented in a large FNSD population (

4).

Clinical assessments.

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–Civilian version (PCL-C) is a 17-item self-report Likert scale (

14) based on DSM-IV-TR (

15) with high internal consistency (

16). It has been used for screening and diagnostic testing and for tracking changes in symptoms (

17). A higher score indicates a greater symptom burden. For the purpose of some of our analyses, we dichotomized the cohort into those with PCL-C scores <45 and those with scores at or above this cutoff value(≥45). This cutoff value was based on the level recommended by the U.S. National Center for PTSD (

18) for screening for clinical PTSD in tertiary centers with expected high rates of PTSD in patient cohorts.

Self-report questionnaires used to assess other aspects of mental, physical, and social well-being included the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9), a nine-item questionnaire widely used to measure depressive symptoms (

19); the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 (GAD-7) scale, a seven-item tool used to measure levels of anxiety (

20); the Patient Health Questionnaire–15 (PHQ-15), a 15-item measure of somatic symptoms (

21); the Short-Form Health Survey–36 (SF-36), a 36-item generic health-related quality of life measure (

22); and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS), a five-item tool used to measure the extent of social impairment (

23). The statistical qualities of these questionnaires among this patient population have been previously described (

6).

Statistical Analysis

Data from any patient who completed the pretherapy questionnaire and attended at least one psychotherapy session was included in the respondents versus nonrespondents analysis (whether or not he or she provided posttherapy data) (for a visual depiction of the number of sessions offered to and attended by the patients, see Figure S1 in the online supplement). Patients who attended at least one session of psychotherapy and returned posttherapy questionnaires were included in pretherapy versus posttherapy analyses. Missing data were handled according to the scoring manuals. Data were analyzed with SPSS (version 25.0).

The data for all measures were nonnormally distributed according to the Shapiro-Wilk test. Therefore, medians and interquartile ranges are reported, and nonparametric tests were used. Independent-samples Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare age, and chi-square tests were used to compare differences in demographic and clinical variables as appropriate.

Pre- and posttherapy questionnaire scores were compared by using related-samples Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. The Holm-Bonferroni method was used to correct for multiple comparisons by using a p value <0.0063 to determine statistical significance. R was calculated as a measure for the effect size of the intervention and interpreted with standard cutoff values (

24). The relationship between changes in psychological questionnaire scores and health-related quality of life before and after the intervention was explored by using Spearman’s rho correlations. The strength of association (r) was interpreted with standard cutoff values (

25). Multiple linear regression analysis was used to examine the contributions of changes in other variables to the variance of health-related quality of life and changes in PCL-C scores.

The likely clinical relevance of changes in PCL-C scores was assessed in two ways. First, by using a previously determined cutoff value of 45 (

6), we differentiated between patients with high PCL-C scores (≥45) and those with low scores (<45) before and after treatment. Second, a reliable and clinically significant change analysis was carried out (

26). This analysis was used to identify the changes in PCL-C scores that were both statistically significant and clinically reliable. To be deemed statistically significant, the posttherapy PCL-C score had to exceed a reliable change index score of 13.7, as determined by the model. Then, to be deemed clinically reliable, the change score had to fall within 1.96 standard deviations of the mean for a nonclinical reference population of students who completed the PCL-C (

14,

27). This method yields the following five categories of change in PTSD symptoms: clinically significant improvement, numerical but not statistically significant improvement, no change, numerical but not statistically significant worsening, and clinically significant worsening.

Results

Respondents Versus Nonrespondents

The median age of patients referred for psychotherapy was 41.0 years (interquartile range [IQR]=28–51). Patients who provided follow-up data (respondents) were older than those who did not (respondents: N=210, median=44 years, IQR=29–53; nonrespondents: N=257, median=39 years, IQR 27–49; p=0.039). Respondents and nonrespondents did not differ in terms of other baseline clinical features or scores on the PCL-C, GAD-7, PHQ-9, PHQ-15, WSAS, and SF-36.

Psychotherapeutic Intervention

The median number of sessions offered across the entire patient population was 14 (IQR=6–22), and the median number attended was 11 (IQR=3–20), with a median session attendance rate of 83%. Nonrespondents were offered a median of seven sessions (IQR=2–16), and the median number of sessions attended was 4 (IQR=1–13). Respondents were offered a median of 21 sessions (IQR=13–24), and the median number of sessions attended was 19 (IQR=11–21). The difference in the number of attended sessions between the two groups was statistically significant (p<0.001).

Changes in Psychological Questionnaire Scores After the Intervention

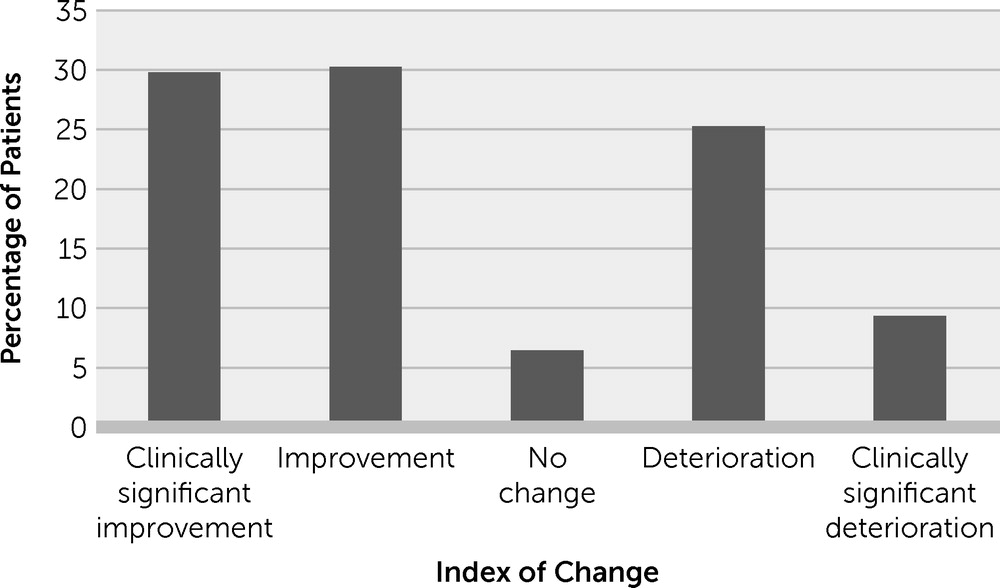

There was a significant decrease in PCL-C scores from pretherapy to posttherapy with a small effect size (pretherapy: median=53, IQR=34–66; posttherapy: median=40, IQR=25–59; Z=−4.61, p≤0.001, r=0.31). The median posttherapy PCL-C score fell below the cutoff value of 45, and the percentage of patients with scores above the cutoff value (high PCL-C score group) dropped from 59% to 44%. The results from the reliable and clinically significant change analysis are shown in

Figure 1. Significant improvements from pretherapy to posttherapy were also obtained with scores on the PHQ-9, GAD-7, PHQ-15, WASAS, and SF-36 (

Table 1).

By using change in PCL-C scores as the dependent variable and change in other psychological outcome measures and demographic data as independent variables, the regression equation was statistically significant (F=25.5, df=8 and 197, p<0.001) and explained 51% of the variance in PCL-C score change. Changes in PHQ-9 and PHQ-15 scores and pretherapy employment status independently contributed to the variance in the change in PCL-C scores (for further details, see Table S1 in the online

supplement).

Discussion

In this study, patients seen by specialists in an FNSD service had high levels of PTSD, depressive, and anxiety symptoms; impaired social functioning; and low health-related quality of life. While the absence of control data or randomization means that we cannot be certain that any changes were attributable to psychotherapy, we observed improvements in psychological and health-related quality of life scores among those engaged in the integrative relational psychotherapeutic approach provided by the FNSD service.

As we reported in our published pretherapy cross-sectional study (

6), 59% of the subgroup of patients who subsequently engaged in treatment and completed posttherapy self-report questionnaires were in the high PCL-C score range. Whereas the pretherapy median PCL-C score was above the cutoff value (≥45) for a high PCL-C score, the posttherapy median PCL-C score was below this cutoff value (<45), and the proportion of patients in the high-score group was reduced (i.e., 59% vs. 44%). The decrease in the PCL-C score exceeded the previously reported minimal clinically important difference of 10.2 points (

28). Three times as many patients in this study reported clinically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms than clinically significant worsening of PTSD symptoms (30% vs. 9%). Among the remaining patients, 30% had a numerically but not clinically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms; 25% experienced a numerically but not clinically significant worsening in symptoms; and 6% experienced no change in their symptoms. Changes in PCL-C scores independently contributed to changes in the mental component score of health-related quality of life measure.

Although PTSD symptom scores in the overall sample improved after psychotherapy, PTSD symptoms increased to a level of severity that was clinically significant for 9% of patients, and symptom severity increased numerically for 25% of patients. This deterioration may be explained by improvements in alexithymia, which was previously reported to be prevalent at baseline among patients with FNSD (34%–90%) (

29,

30). Psychotherapy may have increased patients’ cognitive awareness of their emotional states and led them to score more highly on the PCL-C after treatment. Alternatively, psychotherapy may have reactivated traumatic memories and thus caused, at least temporary, symptom exacerbation. More research is needed to enable psychotherapists to identify patients at risk of worsening with therapy as early as possible.

When patients talk about a particularly distressing event (i.e., a trauma), having them attend to bodily sensations, experiences, and states in the moment is one of the key psychotherapeutic aims for patients with FNSD. Patients may become—or learn to become—aware of an exacerbation of FNSD symptoms or manifestations of an associated arousal response, such as shallow breathing or an increased heart rate. Without downplaying the nature or presence of the trauma, working with symptoms and sensations that arise while communicating with the therapist is likely to be an important stabilizing, grounding, and self-soothing therapeutic element that enables patients to relate to their trauma in a different manner (

12,

31,

32). Research into the resolution of posttraumatic symptoms may be more helpful than identifying the presence or absence of traumatic life events among patients with FNSD.

This study has several limitations. Some social and demographic data with potential relevance were not routinely collected, and this affects the generalizability of our findings. The absence of control data means that we cannot establish causal links between psychotherapy and the changes described. The fact that our data are based on a service evaluation and a truly consecutive cohort rather than the more selective populations typically involved in research studies may make our findings more representative of routine practice but cannot make up for this methodological weakness.

The advantage of the consecutive data collection is diminished by the sizable number of patients with missing posttherapy data. Despite the lack of differences in baseline scores between respondents and nonrespondents, the response rate of <50% limits our ability to generalize the largely positive findings. Respondents were older and had more therapy sessions. We previously observed that older FNSD patients are more likely to engage with psychotherapy (

33). Patients may not have returned their questionnaires for administrative reasons or for a lack of acceptance of their FNSD diagnosis. Acceptance of a diagnosis with a psychological attribution has been previously described as an important factor for positive outcomes (

34).

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, we can conclude that following treatment with psychotherapy, three times as many patients with FNSD showed improvement in PTSD symptoms rather than a worsening of PTSD symptoms. We also observed improvements of other psychopathological symptoms and health-related quality of life. On the basis of these observations, we suggest that controlled and randomized studies of psychotherapy for FNSD are warranted.