Fregoli syndrome is a delusion of misidentification, first described by Courbon and Fail in 1927 (

1). It is characterized by the belief that a familiar person or people are presenting themselves to the affected individual disguised as others, meaning the appearance of individuals in the patient’s environment is accurately perceived, but these individuals, typically strangers, are misidentified as being familiar people in disguise (

2). Commonly, a patient with Fregoli syndrome misidentifies several individuals as being the same familiar person in several different disguises, and the familiar person is often perceived to be intentionally following the affected individual (

3).

Over the past 80 years, delusional misidentification syndromes like Fregoli syndrome have posed challenges to mental health professionals as a result of limited understanding of the etiology (

4), lack of effective treatment (

5), and concerns about risk (

6). Earlier debates about misidentification delusions centered on whether they were best understood as “organic” (i.e., secondary to traditionally defined neurological conditions) rather than “nonorganic” (i.e., “functional” or primary psychiatric disorders) (

7,

8). More recently, however, case-finding studies have noted that this simplistic classification does not account for the potential interactions between etiology and presentation (

9–

11). Indeed, there is emerging evidence of differences in the clinical presentation of misidentification delusions in the context of primary and secondary psychosis. For example, in a recent systematic review of Capgras syndrome, a related delusional misidentification syndrome where affected individuals misidentify familiar people as impostors, cases secondary to neurological disorder revealed lower rates of paranoid delusions and higher rates of cognitive impairment in memory and visuospatial domains (

12).

Although Fregoli syndrome is phenomenologically distinct from other misidentification delusions (

13) and likely arises from a characteristic etiology (

2), to our knowledge, a comprehensive systematic review of the primary literature has never been performed. By using a patient-level meta-analytic approach, we sought to compare the neuropsychiatric features of patients with Fregoli syndrome that arose within a primary psychiatric disorder or secondary to a neurological disorder.

Methods

A systematic review of all published cases of Fregoli syndrome was conducted, followed by a patient-level meta-analysis comparing cases arising from a primary or secondary psychosis. This study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (

14,

15) (for further details, see Table S1 in the

online supplement). The meta-analysis was registered on the Open Science Framework.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We searched five electronic databases (PubMed, Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, and Global Health) for articles published before November 10, 2020, using the following search terms with no date limits: “Fregoli delusion” OR “Fregoli syndrome” OR “delusions of misidentification” OR “delusional misidentification” OR “misidentification.” After removal of duplicates, each article was screened by title and abstract before the full paper was reviewed to confirm eligibility. Relevant systematic reviews and references of included cases were hand-searched for additional cases. The study search was conducted independently by two reviewers (M.T-D. and A.K.D.), and any discrepancies were resolved by a third independent reviewer (G.B.).

Inclusion criteria required articles to be written in English and to include one or more patients with Fregoli syndrome reported at a case level. In instances where one or more articles reported data for the same patient, the more detailed study was used. To determine whether patients met the clinical criteria for Fregoli syndrome, we assessed the reported delusional content against an adapted version of the criteria for identifying Capgras syndrome, as described by Bell and colleagues (

9) (for further details, see Table S2 in the

online supplement). Only cases where diagnostic certainty was “strong” or “possible” were included in the meta-analysis.

Data Collection and Synthesis

An electronic data extraction tool was developed and piloted. Data extraction from all eligible studies was performed by a researcher (M.T-D.). In addition, data from 20% of studies were independently extracted by a second researcher (A.K.D.) in parallel to that of the first researcher, and a third researcher (G.B.) arbitrated over any discrepancies. The following data were extracted from each study: demographic variables, diagnosis, delusional content, other psychiatric features, investigations, and treatment. For case reports, risk of bias was assessed with a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (

16,

17) (for further details, see Table S3 in the

online supplement). By using a 6-point scale, cases were rated as low risk of bias (scores of 5–6), medium risk of bias (scores of 2–4), or high risk of bias (scores of 0–1).

Statistical Analysis

First, summary statistics were computed for the whole sample. Thereafter, a patient-level meta-analysis was performed comparing patients with a primary and a secondary psychiatric disorder. Excluded from the meta-analyses were cases where the etiology was ambivalent or unknown or where insufficient data were reported (i.e., less than two main outcomes were reported). The primary analyses explored neuropsychiatric features, neuroimaging and neurophysiological abnormalities, and response to treatment. Secondary analyses were conducted to assess the content of the Fregoli delusion and neuroanatomical location of brain abnormalities.

A Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare ages between the groups, and a Pearson’s chi-square test was used to evaluate sex differences. Frequencies and percentages were computed, and the differences between the primary and secondary psychosis groups were assessed with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), which were estimated by using random-effects models. Post hoc chi-square tests were conducted to compare the frequencies in right- and left-sided brain lesions in the total sample and in the secondary psychosis subgroup. To assess the robustness of the results, sensitivity analyses were used to explore the effects of risk of bias and effects of diagnosis certainty. Cases at high risk of bias and cases assessed as “possible” Fregoli syndrome according to the adapted Diagnosis Certainty Scale were excluded. All variables were dichotomous except age. The p value was set a priori as 0.05. To adjust for multiple comparisons in the secondary analyses, p values were adjusted by using Bonferroni correction (

18). Statistical analyses were conducted in R, version 4.0.4 (

19), with the

psych (

20),

meta (

21), and

dplyr (

22) packages. The data sets and full-analysis code are available through the Open Science Framework website (

https://osf.io/qygbm/?view_only=f522b34f525c401e9cb0d68d1f890ed6).

Results

A total of 4,656 studies were identified from the study search, and 154 full-text articles were screened (for further details, see the PRISMA flowchart in Figure S1 in the online supplement). The study search yielded 83 studies, which reported 119 cases of Fregoli syndrome.

Patient data were extracted from case reports (N=61, 51%), case series (N=37, 31%), experimental studies (N=12, 10%), and abstracts (N=9, 8%). Overall, 62 patients (52%) had Fregoli syndrome in the context of primary psychoses, and 50 patients (42%) had Fregoli syndrome in the context of secondary psychoses. For the remaining cases (N=7, 6%), a mixed or unknown cause of psychosis was reported, and thus these cases were excluded from the meta-analysis.

We excluded from the meta-analysis cases for which insufficient data were provided (N=23, 19%; see the references in the online supplement), and thus a total of 89 patients with Fregoli syndrome (from 73 studies) were entered into the meta-analysis: 55 patients (62%) with a primary psychiatric disorder and 34 patients (38%) with a secondary cause (for case descriptions, see Table S7 in the online supplement). Of the cases included in the meta-analysis, 79 (89%) were rated “strong” in terms of diagnostic certainty.

Diagnoses of included patients are summarized in

Table 1. The majority of patients with a primary psychiatric disorder had schizophrenia (N=32, 58%). In contrast, patients with a secondary disorder had a more even distribution of diagnoses, with stroke (N=9, 26%) and traumatic brain injury (N=7, 21%) being the most common. Most patients with Fregoli syndrome in the context of a secondary cause had a neurological disorder (N=26, 76%).

Risk of Bias Assessment

The majority of cases were rated as being at medium risk of bias (N=46, 52%), followed by high risk (N=31, 35%) and low risk (N=12, 13%). Individual scores are reported in Table S7 in the online supplement.

Age and Sex Differences

Patients in the secondary psychosis group were significantly older (median=60 years, interquartile range [IQR]=39 years) than patients in the primary psychosis group (median=33 years, IQR=17 years) when assessed with the Wilcoxon sign-rank test (W=510, p=0.002). There was no significant difference in the proportion of females in the primary and secondary psychosis groups (49% and 50%, respectively).

Neuropsychiatric Features

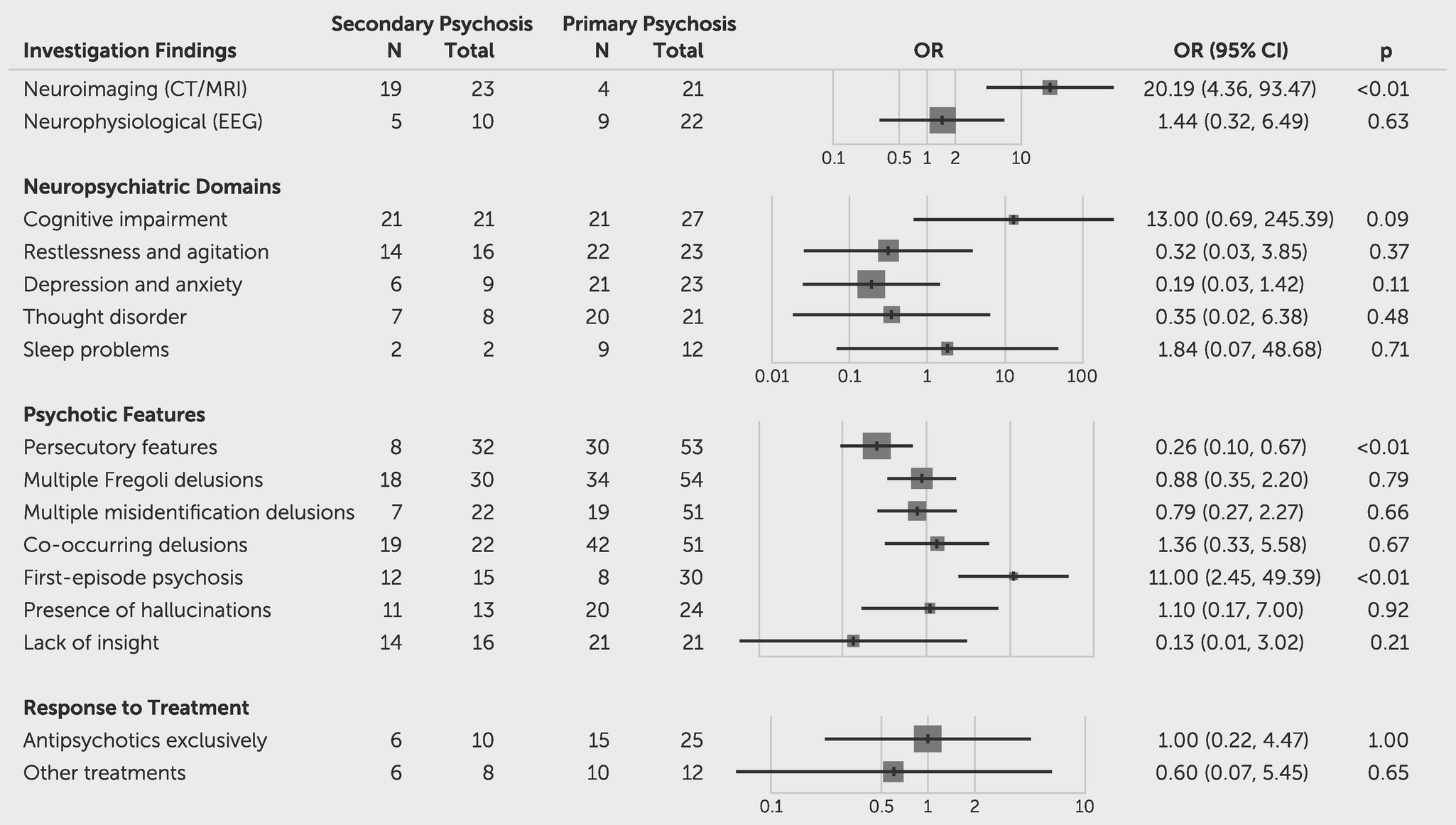

Meta-analysis revealed that patients with a secondary etiology were significantly more likely to experience Fregoli syndrome as part of a first episode of psychosis (OR=11.00, 95% CI=2.45, 49.39; z=3.13, p

=0.0017). In contrast, they were less likely to experience persecutory delusions (OR=0.26, 95% CI=0.10, 0.67; z=−2.76, p

=0.0057). All other neuropsychiatric features showed no differences between groups (

Figure 1; see also Table S4 in the

online supplement).

Neuroimaging Abnormalities

In total, neuroimaging results detected by either computed tomography or MRI were reported for 21 patients (38%) with a primary psychotic disorder and 23 patients (68%) with a secondary cause. Of these patients, four (19%) in the primary psychosis group and 19 (83%) in the secondary psychosis group had neuroimaging abnormalities reported (

Table 2). This difference was statistically significant (OR=20.19, 95% CI=4.36, 93.47; z=3.84, p

=0.0001). We explored the neuroanatomical location of brain abnormalities detected. Almost three-quarters of patients with secondary psychosis had right-hemispheric lesions (N=14, 74%). In addition, more than one-half of patients with secondary psychosis had a frontal lobe abnormality (N=10, 53%). In contrast, the majority of patients in the primary psychosis group had bilateral lesions (N=3, 75%). Random-effects models revealed no significant associations between psychosis etiology and MRI abnormality location (

Table 2). In a direct comparison of right- versus left-sided lesion frequencies, right-sided lesions were more common across the whole sample (χ

2=5.0, df=1, p=0.025), and this remained the case in the secondary psychosis group (χ

2=4.26, df=1, p=0.039). Right-sided lesions were more common than left-sided lesions in the primary psychosis group, although the low total count in this group (one patient with a right-sided lesion and zero patients with left-sided lesions) excluded statistical analysis.

A meta-analysis based on patients with reported neuroimaging results in the primary psychosis group (N=4) and the secondary psychosis group (N=19) revealed no significant differences in neuropsychiatric features between groups (for further details, see Figure S2 in the online supplement).

Delusional Content

The majority of patients with a primary (N=34/54, 63%) or secondary (N=18/30, 60%) disorder experienced more than one Fregoli delusion (i.e., patients who identified more than one identity appearing in the guise of others). The content of the Fregoli delusions reported is summarized in

Table 3. Patients with a secondary psychosis were more likely to mistakenly identify family members than patients with a primary psychosis (OR=4.98, 95% CI=1.96, 12.65; z=3.37, p

=0.007). Between groups, there were no significant differences in the categories of people from the environment who were being misidentified.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses excluding cases at high risk of bias revealed no change in significant findings in the primary outcomes. However, the association between secondary psychosis and misidentification of family members became nonsignificant in the secondary analysis. Sensitivity analyses excluding cases rated as possibly Fregoli syndrome did not lead to any changes in the significant findings.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the differences in neuropsychiatric features associated with patients experiencing Fregoli syndrome related to a primary or secondary psychotic disorder. A total of 119 reported cases of Fregoli syndrome were found in the English literature since the first published description in 1927 (

1), which averages 1.3 published cases per year. Of the reported patients, 42% (N=50) experienced a Fregoli delusion in the context of a secondary cause, most commonly a neurological disorder.

To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive meta-analysis to specifically examine Fregoli syndrome. However, previous research examined the neuropsychiatric features of delusions of misidentification more broadly. An earlier review of 260 case reports of delusions of misidentification explored the most frequent associated neuropsychiatric features, which included paranoid symptoms, depression, auditory hallucinations, and aggressive behavior (

23). In a more recent systematic review of Capgras syndrome, which is the most common type of misidentification delusion, a significant difference in the neuropsychiatric features was observed between patients with a primary and secondary etiology (

12). Specifically, patients with a secondary etiology were more likely to experience visual hallucinations, to exhibit neuroimaging and neurophysiological abnormalities, and to have memory and visuospatial impairments (

12). Moreover, they were less likely to have formal thought disorder, to experience auditory hallucinations, to experience other misidentification and paranoid delusions, and to show violent behavior.

Among patients who underwent neuroimaging, it was notable that right-sided lesions were particularly common. In addition, there was an overrepresentation of patients with lesions in the frontal lobe. The preponderance of right and frontal neuroanatomical lesions in patients with misidentification delusions has been reported in previous studies (

24,

25). Darby and Prasad (

26) investigated a sample of 61 patients with various delusions of misidentification and found that 63% had right frontal lesions and that the frequency was significantly higher than that of lesions in other lobes or in the left hemisphere (

26). Furthermore, in a recent MRI study that examined brain connectivity of lesions related to delusions of misidentifications, the investigators found that almost all the patients in the sample (N=17) had lesions in brain areas functionally connected to the right frontal cortex (

27) and that this was specific to misidentification delusions compared with other neurological syndromes. This highlights the critical importance of the right frontal regions that were found in our sample of patients with Fregoli syndrome. Dysfunction in the right hemisphere and frontal lobe is associated with the misplacement of familiarity, as well as with faults in reality monitoring and memory integration (

28). It is plausible that these cognitive impairments may result in incoherent and false explanations, inducing Fregoli syndrome and other delusions of misidentification.

Persecutory features associated with Fregoli syndrome were more likely to occur among patients with primary psychosis than among those with secondary psychosis. Interestingly, this association was also reported in Capgras syndrome in a study conducted by Pandis and colleagues (

12). This finding may be explained by the high proportion of patients in the primary psychosis group who had schizophrenia, in which paranoid delusions are one of the most common symptoms (

29). Additionally, our results showed that patients with secondary psychosis were older, which is also consistent with findings in studies of Capgras syndrome (

12), as well as with several age-associated causes of delusions of misidentification, including stroke and neurodegenerative disorders (

30).

One of the key findings from the present meta-analysis was that almost one-half of all patients with Fregoli syndrome had a secondary cause of psychosis. This suggests that clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for a neurological etiology, rather than a primary psychiatric etiology, for any patient presenting with Fregoli syndrome and therefore request relevant neuroimaging investigations, such as MRI. Clinicians should be particularly mindful of older patients and patients presenting with a Fregoli delusion in the context of a first psychotic episode, where neurological causality is likely to be more prevalent. However, we sound a note of caution because reviews of Capgras delusion based on case reports and case series have reported high levels of neurological etiologies (

12) and forensic risks (

31), which have not been found in subsequent case-finding studies (

9,

10), potentially suggesting that certain features may be overrepresented in the published literature. Fregoli syndrome may be a phenomenological marker for secondary etiology; however, future case-finding studies remain key to answering this question.

Strengths and Limitations

There are several strengths of this meta-analysis. First, the study comprised the largest synthesis of cases of Fregoli syndrome, to our knowledge, and therefore provides the most comprehensive and up-to-date review of the literature. Second, a case-level approach yielded a highly granular level of detail, including exploration of descriptive psychopathology. Third, we were able to evaluate the diagnostic certainty of cases based on reported phenomenology, providing a high degree of confidence regarding caseness. Fourth, sensitivity analyses indicated that the results were robust to risk of bias and diagnosis certainty.

There are, however, certain limitations to this study. Most cases were extracted from case reports and case series, which generally constitute low levels of evidence. Indeed, most cases were at medium or high risk of bias. Additionally, the inherent nature of case reports and case series meant that these cases were likely to be overly representative of unusual or extreme presentations. This could have led to an overestimation of patients with a secondary cause of psychosis. Furthermore, there was a lack of consistency in the reporting of clinical features across studies, which led to several missing data points, lowering the statistical power and increasing the risk of a type 1 error. In particular, the number of patients with a primary cause of psychosis who reported neuroimaging results was very low. These issues may have introduced publication bias, as well as outcome reporting bias, and therefore caution is warranted in generalizing our results.

Future Directions

Case-finding studies will be required to determine the prevalence of primary and secondary causes of Fregoli syndrome. This information, combined with sensitivity and specificity, would allow positive and negative predictive values to be estimated for phenomenology as a potential guide to secondary causation. However, due to the rarity of Fregoli syndrome, recruitment is likely to present a substantial challenge to such an endeavor. The use of electronic health records may be a fruitful alternative (

9). In addition, structural and functional neuroimaging studies are necessary to further investigations regarding the lateralization of abnormalities to advance our understanding of the neural correlates of Fregoli syndrome.