Although the progesterone deficiency theory has subsequently been questioned (

3,

4), most attempts to define a condition characterized by symptoms appearing premenstrually are still based on the assumption that any symptom displaying this temporal pattern should be regarded as part of the same disorder. In this vein, presence of one symptom of sufficient severity to cause impairment, be it a mood symptom, such as irritability, or a physical symptom, such as breast tenderness, is sufficient for the diagnosis of

premenstrual tension syndrome as defined in ICD‐10 or for the diagnosis of

premenstrual syndrome (PMS) as defined by the American College of Gynecologists (ACOG) (

5). Moreover, in the criteria for these conditions, no symptom is named more important than the other. For the definition of the corresponding condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) editions IV and V –

premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) – the American Psychiatric Association has taken a somewhat different stance in the sense that the presence of at least five different symptoms, one of which must be one of four key mood symptoms, is required (

6). Somatic complaints, such as headache and bloating, are however included also among the PMDD criteria but are lumped together in the last of 11 items.

The aim of this study was to shed light on the self‐reported impact of all different symptoms named in the DSM criteria for PMDD as well as on the possible interrelationship between them. Moreover, the relevance of the DSM requirement that 5 different symptoms should be present for the diagnosis to be made was addressed.

Discussion

Largely in line with previous studies (

4), 9% of the women claimed to be suffering from premenstrual complaints of sufficient severity to cause reduced functioning. The main finding of our study is the dominating role played by mood symptoms in general, and irritability in particular, as the major reasons for self‐reported impairment within this group. In contrast, somatic symptoms such as bloating and breast tenderness, though being experienced by many, were regarded as causing impairment by merely a small minority (

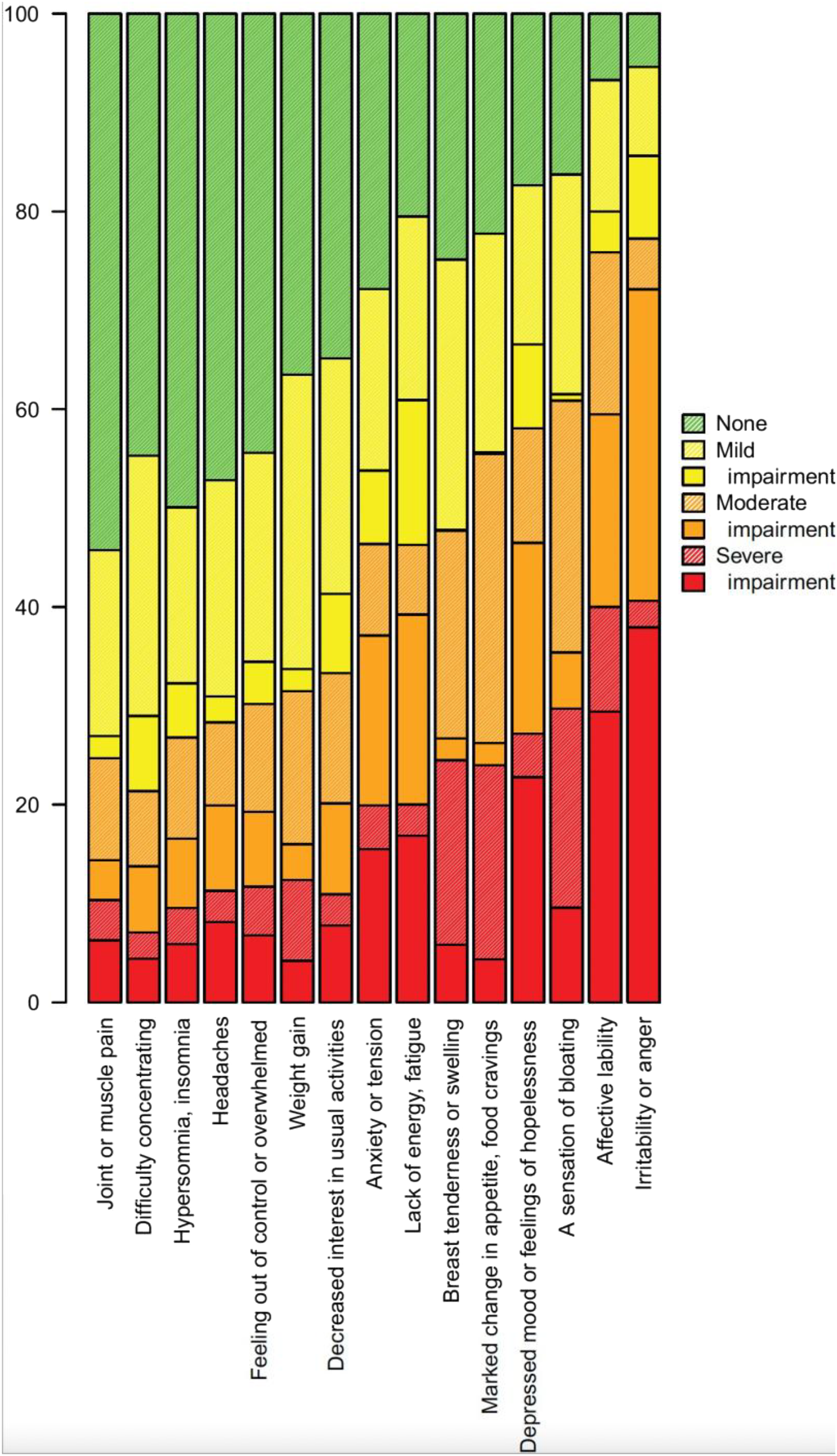

Table 1).

Our finding that somatic symptoms are perceived as less significant than mood symptoms is partly at odds with other reports (using retrospective or 1–2 months of prospective rating) suggesting somatic premenstrual symptoms to be as important as mood symptoms in population‐based cohorts (

14,

15). One reason for this discrepancy may be that our analysis is based on a subset of women who initially had stated that they suffer from impact‐causing premenstrual complaints; thus, somatic symptoms may be as common as mood symptoms in the general population but regarded, in comparison, as less impairing in the most severely affected group. Also, while we specifically asked the participants to address the possible impact of each symptom, most previous studies have assessed the significance of individual symptoms on the basis of self‐rated

severity rather than

impact (

14,

16). That self‐rated severity is not equivalent to impact is however demonstrated by our finding that only 17% of those reporting a severity of 3 or 4 (on a 1–4 scale) for breast tenderness found the symptom to exert an impact (the corresponding number for irritability being 90%).

Some women did report somatic symptoms to cause reduced functioning but most of these also reported impairing symptoms from the mood cluster. Our data hence argue against the existence of a large subgroup of women experiencing impairing somatic symptoms but no impairing mood symptoms. On the other hand, the possibility that many women not passing the screening questions would have reported breast tenderness or bloating as sole symptom, though not feeling impaired by its presence, cannot be excluded.

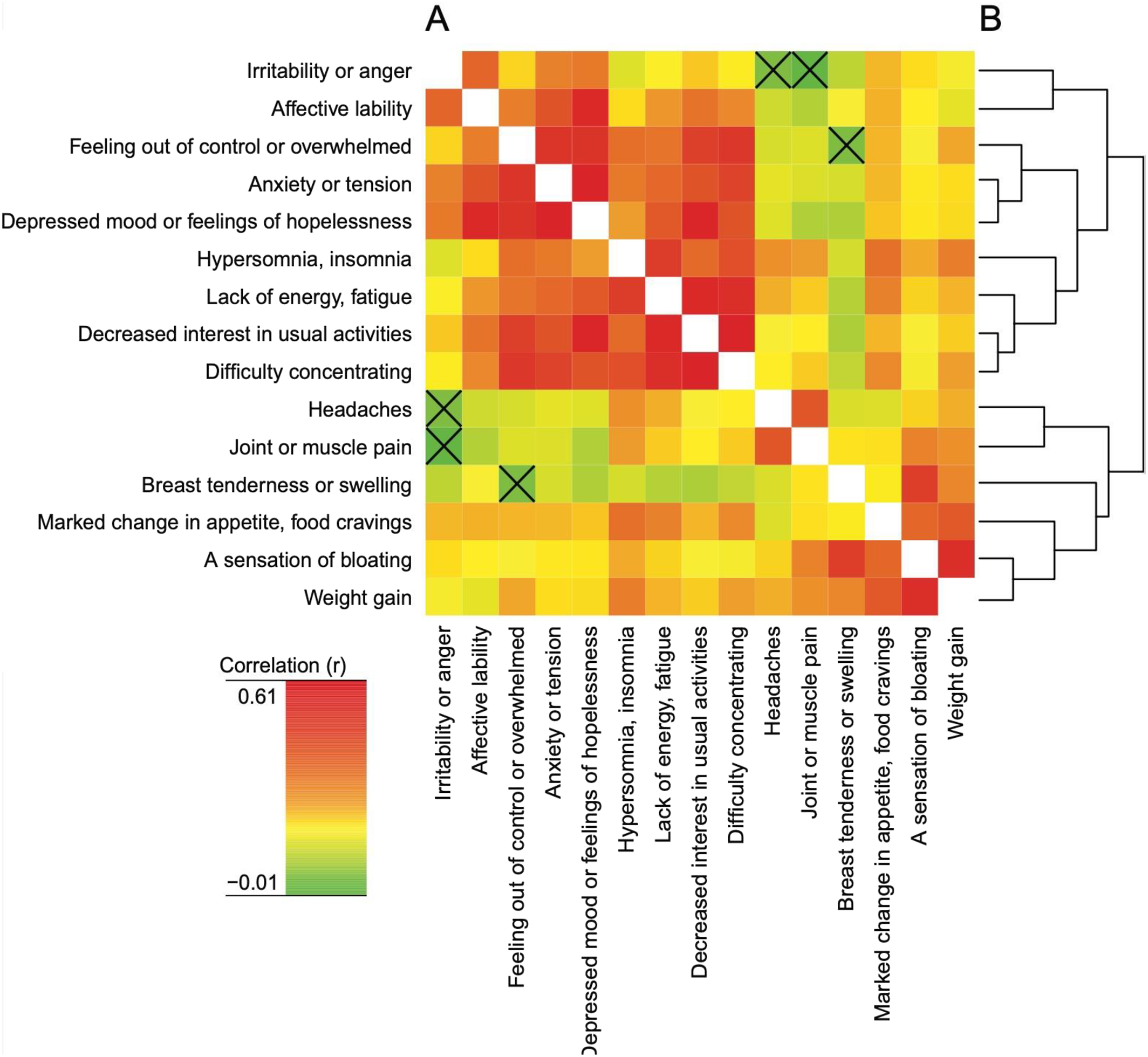

The possible association of somatic and mood symptoms was assessed by means of a cluster analysis suggesting mood symptoms to be separated from somatic symptoms (

Figure 3 and Supplement). These findings are largely in line with earlier studies, regardless of whether these have been based on samples recruited from the general population without any pre‐selection of those with significant symptoms (

17,

18) or from relatively small groups of PMS or PMDD patients (

19,

20). While we hence identified clear‐cut symptom profiles, the correlation analysis however revealed that women rating high severity of mood symptoms tend to report high severity also of somatic symptoms; thus, correlations were observed not only within but also between clusters. It should however be noted that, for example, headache correlated neither with irritability nor bloating, and that joint and muscle pain correlated neither with irritability nor anxiety/tension; in this vein, the NbClust analysis suggested these symptoms to form a cluster of their own. We conclude that regarding these symptoms as parts of the same syndrome as the mood symptoms, and naming them as symptoms in the DSM criteria, may be questioned. Thus, while omitting headache from the symptoms listed in the DSM‐V criteria of PMDD hence seems justified, the decision to include joint and muscle pain may be questioned (

6).

Whereas the distinct symptom clustering suggests that PMDD should not be regarded as

one syndrome, the observation that the two major clusters nevertheless did correlate could speak in favor of the existence of a common pathophysiological factor enhancing the propensity for both mood symptoms and somatic complaints. Two aspects however render it difficult to interpret these associations. On the one hand, it cannot be excluded that the apparent association between severity of somatic and mood symptoms partly be the result of personality‐related differences in proneness to use the extremes of the rating scale (

21,

22), hence yielding artificially high associations, and it is also possible that mood symptoms may render somatic complaints less tolerable than they would otherwise have been. Supporting this possibility, the number of significant associations between symptoms within the somatic and mood clusters, respectively, or within the somatic cluster, was lower when the assessment of associations was based on a dichotomous variable, such as presence (yes/no) or impact (yes/no) of a certain symptom (see Supplement). On the other hand, the fact that we only included women reporting impairing premenstrual complaints may have led to a non‐representative accumulation of subjects experiencing impairing symptoms of one type or another, hence yielding negative correlations for non‐related symptoms and making associations between partly related symptoms appear weaker than they actually are. To address this issue, symptom assessment in the entire cohort, including also those not confirming the presence of impairing premenstrual complaints, would have been required.

Given the clear‐cut symptom clustering, one may suggest that future search for biological markers and new treatments would be facilitated by regarding, for example, premenstrual irritability, on the one hand, and premenstrual breast tenderness, on the other, as different conditions. Of note is that intermittent administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), generally regarded as first line of treatment for PMDD, exerts an impressive effect on mood and behavioral symptoms (

23,

24) but is less effective in reducing somatic symptoms (

23,

24,

25).

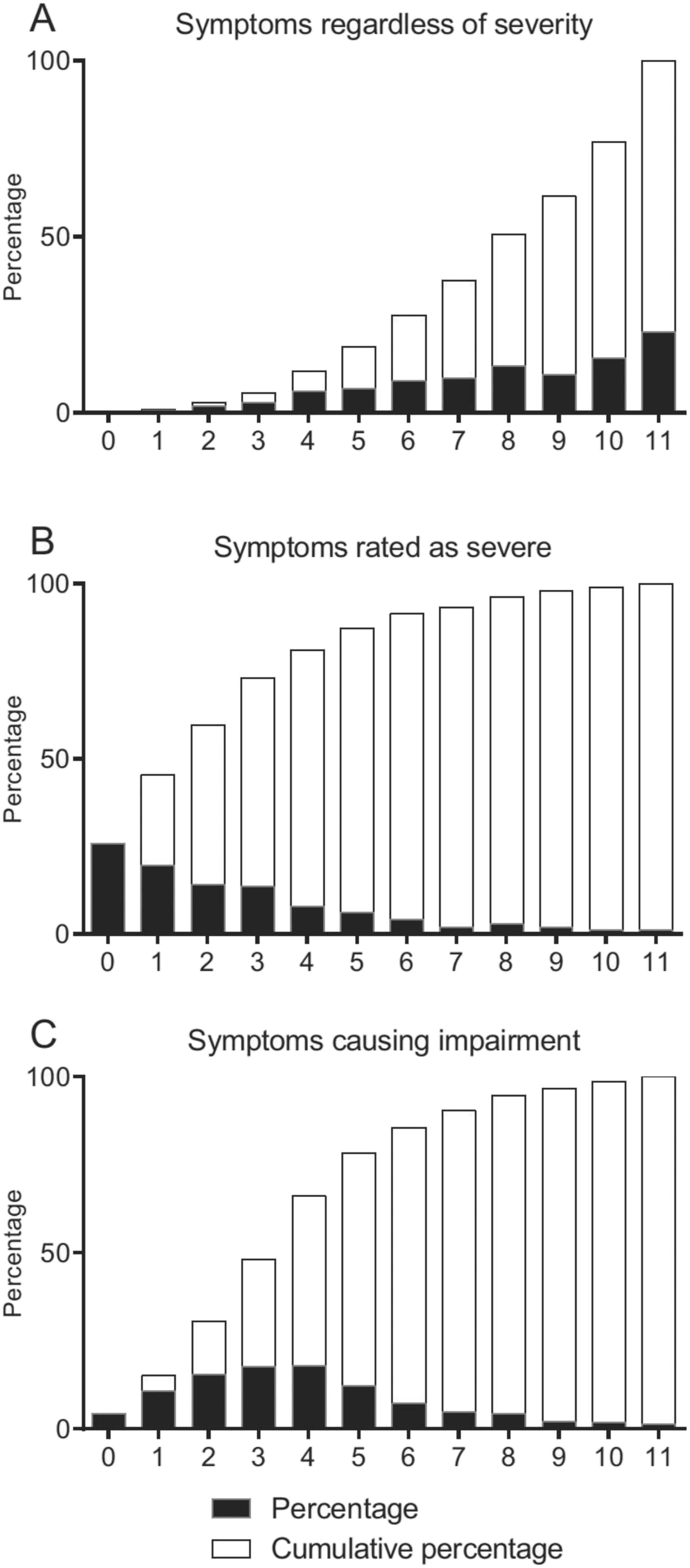

Whereas the PMDD criteria are not met unless 5 symptoms are present, it may be argued that individuals with fewer complaints should qualify for a diagnosis in case these are severe enough to cause impairment. In this vein, one impairment‐causing symptom is sufficient for the diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome as defined by ACOG (

5). However, in line with previous reports (

15), we note that a vast majority (>88%) of those responding affirmatively to the screening questions do confirm presence of at least 5 different symptoms. On the other hand, those reporting each of 5 or more symptoms to cause impairment were much fewer (<35%). To what extent the DSM criteria should be interpreted as requiring each of five symptoms to be of sufficient severity to cause impairment, or if it is sufficient that one of them (or all when combined) cause impairment, is unclear.

It should be noted that our questionnaire is based on the DSM‐IV criteria of PMDD, which, like the ACOG criteria for PMS, require interference with work, usual activities, or relationship with others. However, in DSM‐V this has been rephrased so that, if there is no interference with daily activities, significant distress would qualify for a diagnosis (

6).

Of all symptoms reported to cause impairment, irritability and affect lability (mood swings) were the most common, and considerably more common than, for example, depressed mood or tension. This observation, which is well in line with previous reports also suggesting irritability and/or mood swings to be more common than depressed mood (

4,

15,

26,

27), supports the notion that PMDD should not be regarded as a subtype of depression (

28), and may, as elaborated elsewhere (

29), explain why SSRIs exert symptom reduction with a much shorter onset in PMDD than when used for depression or anxiety disorders. Heightened irritability being the hallmark of PMDD and severe PMS also makes sense from an evolutionary point of view if one regards these conditions as a reminiscence of the oestrous cycle‐related changes in behavior (with the purpose of facilitating reproduction) seen in lower species (

30,

31).

According to the DSM criteria of PMDD, the cyclicity of symptoms must be supported by two subsequent cycles of daily prospective symptom rating. It should hence be underlined that this study only provided a provisional diagnosis of PMDD or severe PMS, that is, one based on retrospective account, and that the results should be interpreted accordingly. However, since an important reason for requiring prospective symptom rating is that many women believing they suffer from PMDD or PMS in fact display symptoms also in the follicular phase, we included a screening question asking the women to consider if they were convinced of being entirely symptom‐free in at least parts of the postmenstrual phase; this maneuver led to the exclusion of 30% of those having responded affirmatively to the first two gateway questions. While this is not a validated technique to render retrospective symptom assessment of PMDD or severe PMS more reliable, we do believe the large percentage responding “no” to this question suggests that it may, to some extent, have served its purpose. Moreover, the outcome of this study with respect to the commonness of different symptoms being well in line with previous reports using prospective rating (

27) does suggest that the studied population was largely the one aimed for. Whereas the feasibility of web questionnaires for the screening of women with premenstrual symptoms gains support from previous work (

32), the fact that responses were not obtained by a face‐to‐face interview is clearly another important limitation.

It should be underlined that the LifeGene cohort cannot be regarded as a representative sample of the general population. In addition to being randomly sampled from the population, there are hence other routes of becoming part of this study including self‐recruitment (

10). Also, given that the participants are requested to take part in many activities within the framework of this longitudinal study, including repeated biosampling, it is not surprising that only 20% of those invited to be index persons have accepted to participate. A population not being representative however does not mean that information on aspects such as risk factors, or (as in the present study) the association between different symptoms, are not generalizable; accordingly, the aspect of response rate has been de‐emphasized in many recent prospective projects (

33). Also, it may be regarded as an important advantage that LifeGene is

not focused on the issue of premenstrual complaints, which might have made women with a particular interest in this subject more likely than others to participate, hence introducing a bias that might be difficult to avoid, for example, in studies requiring prospective symptom rating. In the present study, questions regarding PMDD were instead imbedded within a large survey covering un‐related health issues.

Because of the possible lack of representativity of the present population, and the lack of prospective symptom rating, it however deserves to be underlined that the purpose of this study was not to assess the prevalence of PMDD, but to explore the relative self‐rated impact of the different symptoms listed in the DSM criteria – as well as their interrelationship – in a large group of women for which a web‐based questionnaire was used to make a provisional PMDD/PMS diagnosis. We see no obvious reasons why this population should differ markedly in these regards from more properly diagnosed women with PMDD or severe PMDS; yet the results should be interpreted with this caveat in mind.

In summary, premenstrual mood and behavioral symptoms, and in particular irritability, were far more important as reasons for impairment than somatic symptoms in the studied cohort. Whereas it cannot be excluded that there is a common factor enhancing the susceptibility for both mood and somatic symptoms, the clear‐cut symptom clustering justifies the question if all premenstrual complaints should indeed be regarded as parts of one syndrome.