Summary of Findings

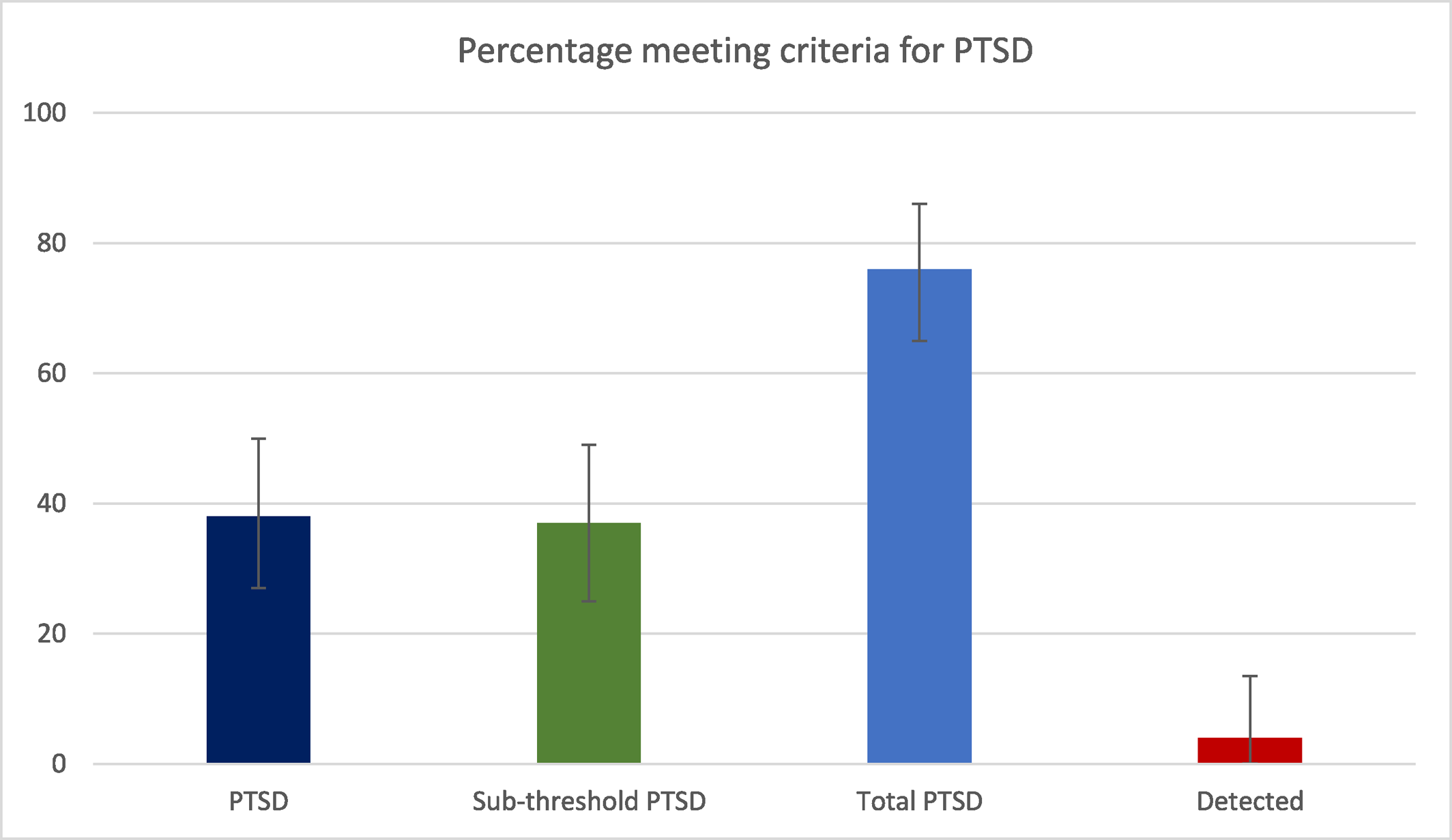

In this cross‐sectional study almost all participants reported experiencing at least one traumatic event that met DSM‐V criterion A for PTSD, and the large majority were exposed to multiple types of trauma. DSM‐V criteria for PTSD were met in 38% of the sample, with an additional 37% meeting criteria for sub‐threshold PTSD.

Our estimate for prevalence of PTSD in those with a psychotic disorder is within the range reported in schizophrenia in one systematic review (

24) and close to the median prevalence estimate of 31% in those with psychotic disorder in another (

11). This estimate is far higher than the proportion of people diagnosed with PTSD in the mental health NHS Trust from which our participants were recruited, where only 1.1% of people with a diagnosis of psychosis also had a diagnosis of PTSD. The paucity of recorded PTSD diagnoses that we observed in patients' notes with psychosis diagnosed is consistent with other studies (

11).

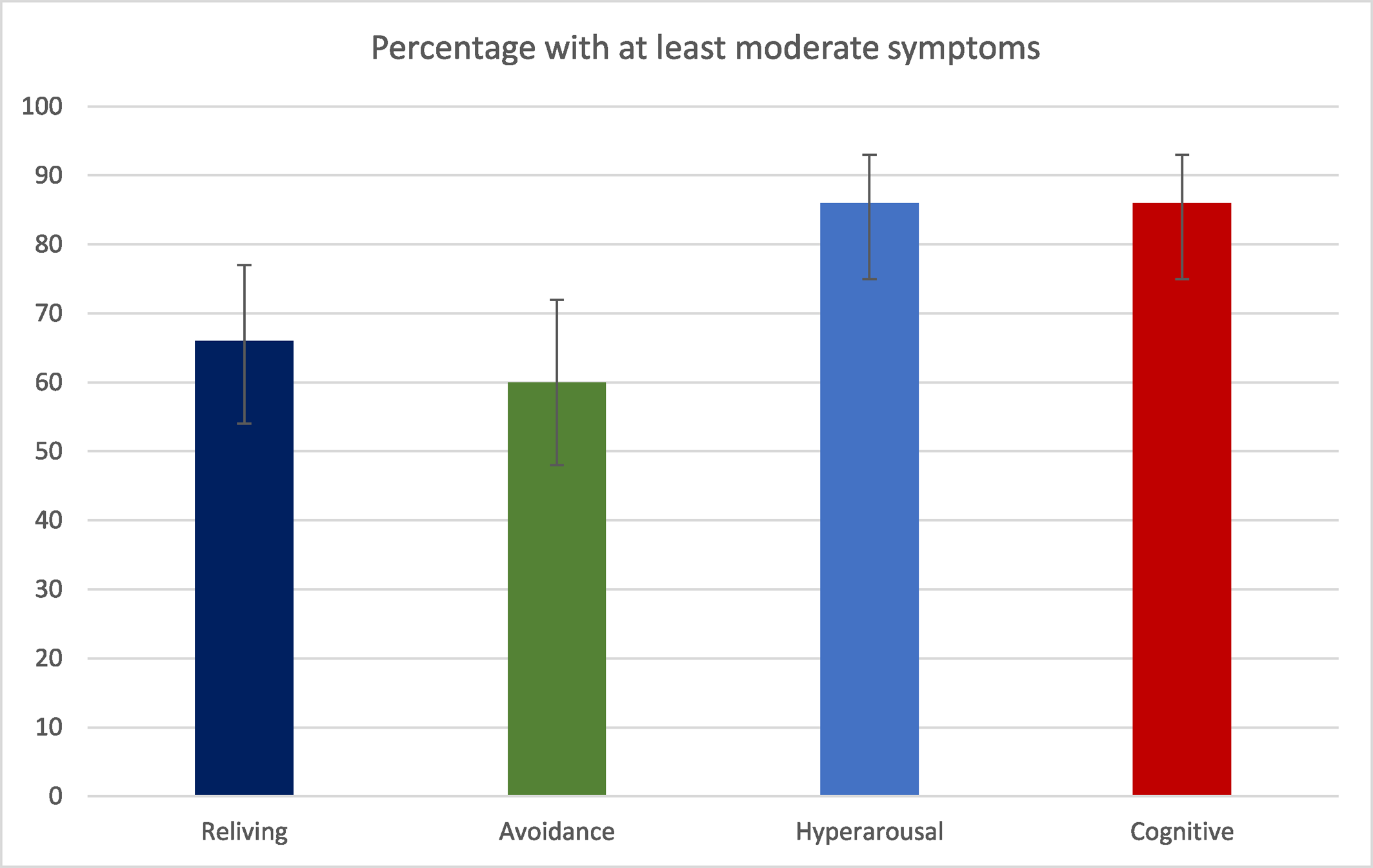

Likely reasons for the low rate of PTSD diagnosis are: i) that clinicians are not recognising or detecting PTSD in people with psychotic disorder, ii) a perception that a diagnosis of PTSD is less necessary than other diagnoses for the purpose of accessing services or treatment, or iii) a lack of confidence in teasing apart PTSD and psychosis symptoms. Whilst hyper‐arousal and negative thoughts/feelings were the commonest PTSD symptom clusters in our sample, reliving experiences such as intrusive thoughts/images were also common, and seem less prone than other cluster to be misattributed to or overshadowed by a psychosis diagnosis.

Where traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms arise before the onset of a psychotic disorder, it is plausible that the onset and maintenance of psychotic experiences are caused by inadequately processed traumatic memories (

25). High levels of emotion during a traumatic experience, and mechanisms such as dissociation to help manage this, could lead to fragmentation of memories that give rise to psychotic phenomena (

26). For example, intrusions could be experienced as hallucinations if they are not recognized as trauma memories and attributed externally instead (

27). However, more research is required to better understand how traumatic experiences result in psychotic phenomena (

28).

The majority of participants in our study believed their mental health problems were linked to their past traumatic experiences, consistent with trauma‐based models of psychosis development (

34) rather than biological models of causation that have dominated the field over many decades and that have sometimes led to the dismissal of such views.

Around two thirds of participants in our study were interested in trauma‐specific therapy, with interest in receiving therapy being stronger in those who reported more severe PTSD symptoms. Given that PTSD appears to both increase the risk of developing psychosis and worsen its outcome, and that service users express a desire to engage with trauma‐specific therapy as we demonstrate here, it follows that an evidence base evaluating trauma‐focused psychological interventions (that are NICE‐recommended treatments for PTSD) is needed in people with ARMS or psychotic disorders.

The results of recent systematic reviews suggest that trauma‐focused treatments are effective at improving symptoms of PTSD in people with psychosis (

29,

30) and that they have a small effect on reducing the positive symptoms of psychosis, although evidence for the latter is less consistent (

31). Further trials of trauma‐focused therapies to prevent the onset of or improve outcomes in psychosis are required (

32,

33).

Strengths and Limitations

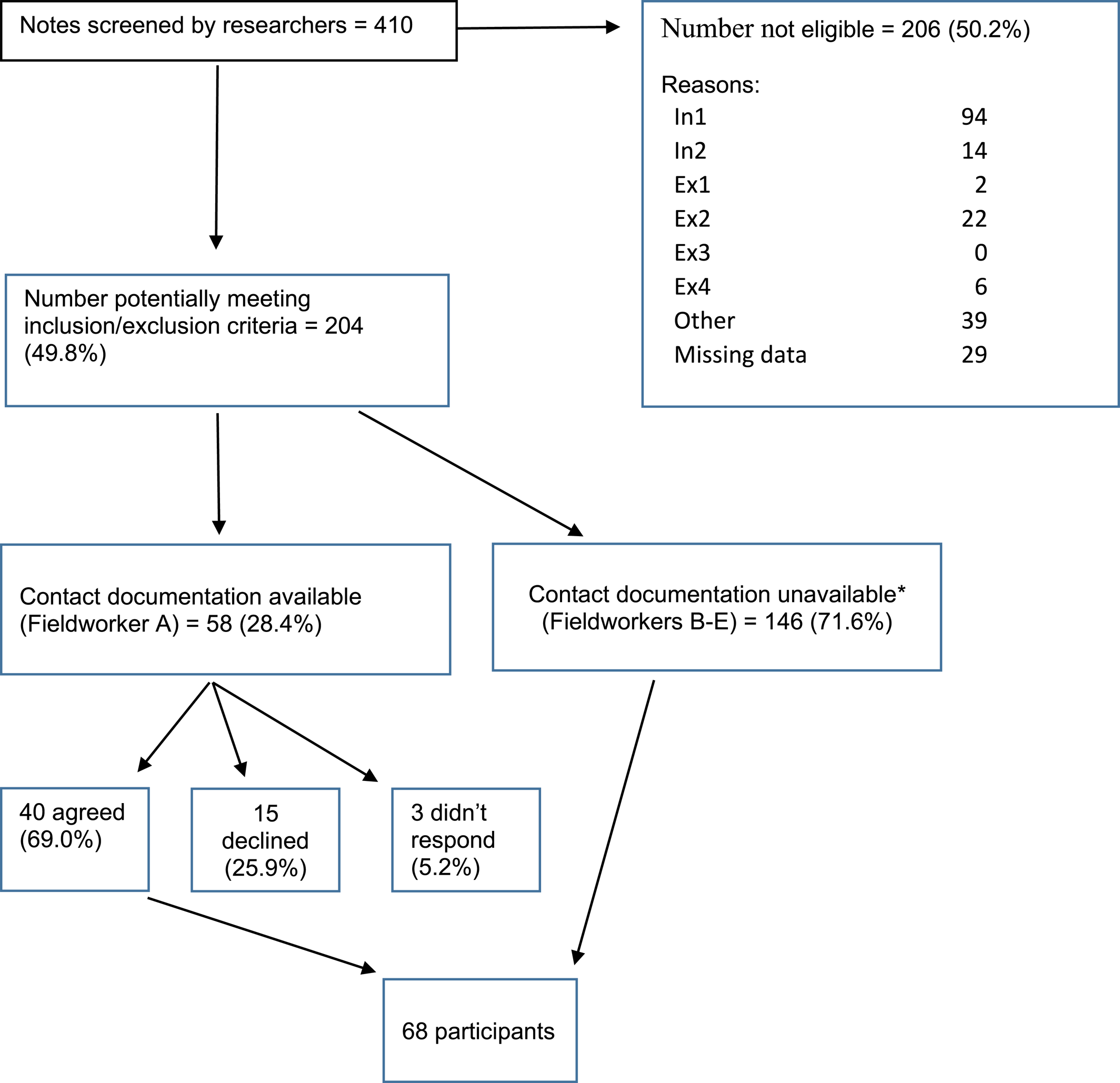

The strengths of this study are that we recruited participants from various NHS clinical teams to gain representation of patients with psychosis across the whole spectrum of secondary care service, and our sample size is large enough to be adequately powered to estimate the proportion of people with trauma and PTSD symptoms with reasonable precision. Furthermore, we supplemented this by exploring patient views on the relationship between trauma and psychosis, as well as views on receiving trauma‐focused therapy that have rarely been described in the literature.

However, our study also has a number of limitations. First, as this was a cross‐sectional study it is not possible to rule out the possibility that trauma exposure and subsequent PTSD symptoms occurred secondary to the presence of a psychotic illness. However, the age of trauma exposure and date of diagnosis suggest that this is not the case in most instances, and that PTSD symptoms pre‐dated the onset of psychotic phenomenology. Second, our response rate estimate of 62% means it is possible that our estimates of trauma exposure and prevalence of PTSD might be overestimated if service users without a history of trauma were less likely to respond than those with such a history. It is also possible that other elements of our recruitment process, such as the use of clinicians as well as non‐clinicians with recruitment, may have influenced who participated in our study and the estimates we observed. Third, we used the PCL‐5 self‐report measure of PTSD symptoms rather than the CAPS semi‐structured interview that is the gold standard for assessing PTSD; hence it is possible that we over‐estimate prevalence of PTSD in our study. However, the PCL‐5 is a well‐validated tool for assessing PTSD, whilst a systematic review of undetected PTSD in secondary care mental health services suggested estimates of PTSD were similar for self‐report and interview‐based measures, with type of assessment explaining little of the heterogeneity in estimates (

11).

Implications

Our study highlights the wide range of traumatic events that service users may link to their psychotic experiences, from childhood abuse to bereavement in adult life. A focus on interventions that target these traumatic life events through memory processing therapies, such as EMDR or TF‐CBT, might provide us with new therapeutic avenues for a substantial subgroup of people with psychosis. Consistent with this, the majority of patients in our study believed there was a clear link between their trauma and their psychotic symptoms, and most expressed an interest in receiving a trauma‐focused therapy (

27,

34).

It is also clear that the current reality for people with psychosis in secondary care mental health services is that PTSD is often undetected (

11). This underlines the need for increased awareness and responsibility on mental health services to identify and address the effect of trauma on service users, as has been previously highlighted (

35,

36,

37), and to evaluate approaches for trauma‐informed care (

38).