Many veterans returning from combat experience residual mental and physical ramifications. Addressing veterans' physical and mental health is crucial to fostering reintegration, readjustment, and overall well‐being for this population (

1).

While estimates vary, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been a significant diagnosis in post 9/11 veterans, with reports demonstrating between 16% and 32% incidence (

2,

3). PTSD is often accompanied by comorbid mental health conditions and substance use disorders, which can impact level of ability, quality of life, and reintegration into society after combat (

4,

5,

6).

Veterans' advocates' research shows that between 10% and 20% of all Iraq veterans have incurred a TBI over time (

7). This statistic corresponds with reports that 352,612 service members were diagnosed with TBIs between 2000 and 2016 (

8). Additionally, it is estimated that 21,000 service members suffer a TBI annually (

7). Given the prevalence of TBI in the military population, it is a debilitating diagnosis with potential long‐term consequences to veterans, including decreased quality of life, cognition, and emotional functioning (

8). It is estimated that up to 50% of veterans diagnosed with TBI also meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD, making these conditions often comorbid in military veterans (

9).

According to the Mental Health Mobility Service Dog Initiative through the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), SDs have been identified as an optimal intervention or treatment approach in addressing veterans with chronic mobility issues associated with a mental health condition like PTSD and/or TBI (

10). Currently, there is no support for SDs for veterans with psychological or mental illness, without a combined physical impairment (

11).

Presently, the use of SDs continues to increase as an emerging treatment modality for veterans with a history of PTSD and/or TBI (

12). Service dogs (SDs) can alleviate many of the symptoms of PTSD and/or TBI, including but not limited to helping veterans remain calm and interrupting a potential panic or anxiety attack by helping their owner focus on petting the dog and re‐centering on the present, ideally preventing and/or mitigating the panic attack (

13). SDs are trained specifically to be paired with each individual veteran based on their respective symptoms and needs, but the variability in these training techniques is significant (

1,

14). Additionally, the overall cost to train an SD, which averages approximately $25,000 per dog, can ultimately prohibit veterans from obtaining and eventually benefiting from their therapeutic assistance (

15). Veterans with mental health concerns have self‐reported that specially‐trained SDs are able to intervene with the manifestations of symptoms, thereby preventing suicidal and aggressive behavior. Research supporting these empirical findings is scarce due to cost, lack of standardization in training techniques, and lack of funding (

16).

STUDY RATIONALE

Empirical knowledge is lacking documentation of the experience of veterans with TBI and/or PTSD utilizing SDs as a tertiary treatment modality (

17). Addressing this gap will help build foundational knowledge to understand veterans' experiences, and the benefits, barriers and challenges associated with the use of SD. This qualitative research study had two primary aims: to investigate the perceived efficacy of utilizing SDs as a tertiary treatment modality in veterans with TBI and/or PTSD, and to examine the barriers and facilitators associated with obtaining a SD.

Background and Significance

The impact of PTSD and TBI symptoms on mental health functioning in returning veterans is significant (

18). Symptoms of PTSD and TBI can have an adverse effect on overall quality of life, including but not limited to, social, occupational, and relational aspects, among others (

19). Furthermore, every day 22 veterans take their own lives, about one suicide every 65 min (

20). The annual suicide rate among veterans is about 30 for every 100,000 of the population, compared with the civilian rate of 14 per 100,000 (

21). PTSD and TBI also incur significant cost to the healthcare system, with resources required for treatment relating to physical and mental health for returning veterans at a median annual cost per patient being in the range of $1500 to $6000 (

18).

Assistance and companion dogs have long been used to aid with various conditions and disabilities. Therapy dogs, SDs, and emotional support dogs vary in terms of type of assistance offered and can include guide dogs for the blind or visually impaired; SDs for seizure alert and response; and SDs for diabetes detection and alert, among others (

22). According to Federal Law, a Service Animal is not a pet; the Americans with Disabilities Act states that a Service Animal is any animal that has been individually trained to provide assistance or perform tasks for the benefit of a person with a physical or mental disability, which substantially limits one or more of the person's major life functions (

23,

24).

The degrees of differences among these dogs should be noted, as each type of dog is not the same and cannot carry out the same tasks as another, due to variations in training (

23,

24). The results from a 2014 study conducted by the Department of Veterans Affairs showed that SDs trained to support veterans with PTSD can decrease the severity of their symptoms better than dogs classified as emotional support dogs (

25).

METHODS

Participants

The study recruited participants through an established partnership with Leashes of Valor (LOV), a nonprofit organization located in Milford, VA, that provides highly trained SDs to disabled Veterans. LOV trainers are holders of the International Association of Canine Professionals and American Kennel Club certifications. Participants were invited to participate via a recruitment flyer that was posted on various social media channels and distributed via LOV's email Listserv. Eligible participants were veterans over 18 years old, diagnosed with TBI and/or PTSD, who were currently paired with a SD that met LOV training requirements. Individuals diagnosed with Military Sexual Trauma were excluded from this study due to the differences in SD utilization involved with trauma etiology.

Participants were screened via telephone regarding eligibility requirements. Participant interviews occurred over the phone due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Participants consented verbally prior to start of the interview with the understanding that the participant may revoke this consent at any time in the research process. Participation in the study was voluntary and confidential as all study data remained de‐identified. The 10 recruited veterans were assigned an identification number, only identified by the coordinating identification number, and stored on a secure server that was password protected. Ten veterans paired with a SD were included in the initial sample as data saturation was achieved at the conclusion of the interviews. The study was approved by Thomas Jefferson University Office of Human Research Institutional Review Board.

Procedure

This qualitative study utilized open‐ended, semi‐structured interviews with veterans diagnosed with PTSD and/or TBI, who were currently paired with a SD (

n = 10). These in‐depth, semi‐structured interviews utilized an interview guide that included 16 prompts and was created by the study team, which included an expert in the field of veteran research, as well as consultants with military backgrounds. The interview guide consisted of open‐ended questions about the participants' perception of the health benefits and effectiveness of using SDs. The interview questions were pre‐tested for semantic and attitudinal feedback by three individuals, similar to the sample population. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed by a professional transcription service and validated by the study team (Supporting Information

S1).

The study team developed initial codebooks from reading all 10 transcribed interviews. Each team member read and coded two transcripts to construct preliminary codes and their definitions, and then the research team collaborated during three sessions using an iterative coding process until consensus agreement was reached and a final codebook was complete.

Data Analysis

Two independent coders independently analyzed each transcript using NVivo qualitative software for themes relating to the participants' perceptions about the health benefits and effectiveness of the use of SDs with veterans diagnosed with PTSD and/or TBI. Each independent coder utilized a systematic approach to data analysis based on grounded theory methodology (

26). Theoretical sampling was used until data saturation was achieved based on the emergent themes and categories during data analysis (

27,

28).

These initial codes and concepts formed the foundation for development of themes and generation of theories through an inductive process of subsequent memo writing and data interpretation (

26). Analytical decision‐making and theoretical insights were included in the memo‐writing process and compared between coders for congruence. The research team members compared analyses and jointly decided upon the major themes presented in a process of consensus coding. This process continued until full agreement was reached for all transcripts. Themes were examined for similarities and disparities, as well as potential linkages between them (

26). Inductive analysis using correlation with Pearson's

r values demonstrated relationships between themes and guided the generation of the grounded theory. The research team members utilized cross‐checking of codes and themes to reinforce truthfulness and rigor of the data analysis (

29).

RESULTS

Sample Demographics

Sociodemographic data are displayed in

Table 1. Participants ranged in age from 34 to 66 years. The sample identified as 80% male and 20% female, with all participants reporting their marital status as married. The sample's self‐reported ethnicity was 100% white. Participants reported 70% residing in a single‐family home, 20% in a modular home or trailer, and 10% in an apartment with total number of individuals in the home ranging from two to five. Participants reported branch of service as 60% U.S. Army, 20% U.S. Navy, and 20% U.S. Marine Corps with four to 27 years of service, and two to 23 years since discharge from the military. Veterans reported one to 15 years since diagnosis, with 0 to 15 years between leaving the military and getting their SD. The reported duration of training the SD received ranged from 3 months to 2 years and 4 months. Veterans reported 100% traveled by car or walked with their SD in commercial buildings, service areas such as a doctor's office, and on public streets or recreational areas. Most veterans reported they also traveled with their SD by bus (80%), train (60%), or airplane (90%).

Themes

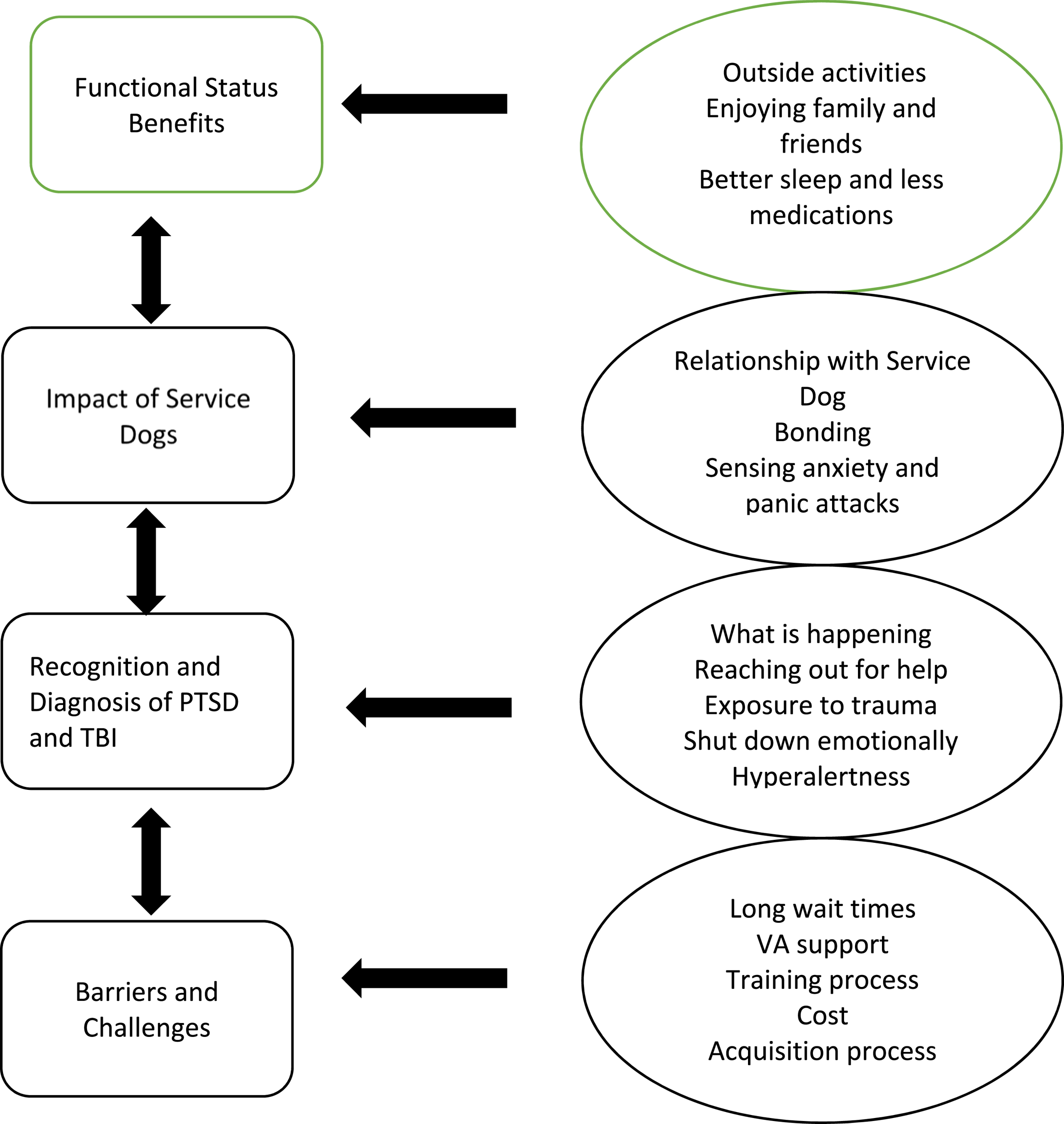

The findings from the extensive thematic analysis produced four themes. The most prominent themes were Functional Status, Impact of an SD, Recognition and Diagnosis of PTSD and TBI and Barriers and Challenges of SD Acquisition. Our grounded theory describes the relationships between themes and subthemes and was generated through numerous iterations of data review. This is displayed in

Figure 1. The following section describes these findings in further detail.

Functional Status

The most prominent theme, functional status, reflected the participants' perception of their functional status after having been paired with their SD. Thematic analysis revealed a contributory relationship between the following subthemes: increase in activities outside of home, enjoying outings with friends and family, improvement in sleep and decreased need for medications for anxiety and panic attacks.

Participants described their diverse military experiences and the bond that they felt with their fellow warriors. Leaving this culture upon return to the civilian world impacted their functional status. Military service was often described while discussing incident and diagnosis. However, some participants explained that more than one incident fostered their diagnosis. Additionally, some participants described their diagnosis as complex and multifaceted.

Recognition of Symptoms

Participants sometimes didn't realize they were having symptoms until someone else told them. They were trying to make sense of exposure to trauma during deployment and what they were feeling post deployment and reaching out for help.

They reported feeling worn out or drained, emotionally shut down or numb. Some participants also reported snapping at others and having a very short fuse, hyperalertness, or panic attacks, especially in crowds. Participants also reported experiencing racing heart, feeling hot, feeling like they had to get out of a social situation instantly, depression, anger, anxiety, foot tapping, sweating, breathing changes, insomnia, nightmares, and sometimes violent night terrors. A few participants reported loud noises and heat as triggers. Participants also reported memory issues, trouble focusing/concentrating, anomia, migraines, seizures, and uncontrolled crying. A few participants described being paired with their SD mitigated their panic attacks and significantly decreased their incidence from a few times per week before the SD to none now.

Treatment

Participants described utilizing a variety of traditional and alternative treatments to manage their symptoms. These included medications, counseling, psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, muscle testing, meditation, alpha‐stim, equine therapy, swimming with sharks, acupuncture, healing touch, journaling, reading self‐help books, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, virtual reality, and exercise. Many participants found some of these treatments helpful, but all felt the addition of their SD was particularly beneficial to their treatment regimen.

Oh yeah, I tried it all. I was on medication, clonazepam, sertraline. I tried virtual reality, I did meditation, I went through the whole regiment.

…everything was a little bit helpful. But the silver bullet was the dog.

Some participants described the complexity of their treatment, and the need for commitment to continued therapy to address the many components of their diagnoses.

Kind of what my therapist said to me was, “27 years in the military and nine different combat tours, this is not something you get over in three weeks of therapy, okay?” He says, “You're going to be with me for a while.” And they call it compound PTSD where it's not just one trauma and people come in and say, “Okay, what's your trauma?” “There's a multitude of traumas that happened, and we had to kind of unpack each one of those, we had to go back to 1983 and Grenada.” “I was 23 years old and jumping into what we thought was a secure airfield and it wasn't and watching people, really for the first time in my life, get mowed down by machine guns.”

Some of the participants still utilized medications as part of their treatment regimen, and most felt the combination of therapy and medication along with their SD was effective at managing their symptoms. Other participants described a reduced need for medication to control daily symptoms and sleep (one stated a 75% reduction in medication usage), while others described not needing any medication after their SD was introduced to their treatment regimen.

I don't require as much medication to sleep at night. I don't require as much medication during the day to keep my symptoms in check.

A few participants also described the use of negative treatment alternatives and self‐medication with alcohol prior to being paired with their SD.

Earlier on, when I didn't necessarily have the best coping skills, that might be go drink yourself till you pass out and deal with it later kind of deal.

Service Dog Impact

Some participants described that prior to being paired with their SD, everyday tasks were extremely challenging and potentially stressful situations. One participant reported that he stopped going out, going shopping, going to the grocery store, or going to family gatherings. Sometimes this would cause stress on this participant's relationship because his wife didn't understand. A few participants also reported that having their SD mitigated the stress because they knew having the SD there would help control their symptoms.

I just started noticing that I was really holding my family back from experiencing things, and if I tried to say I didn't want to do that, my wife didn't understand and I wasn't communicating it well, so it would lead to a fight of, why do I not want to do that?

“… we were trying to check out at the store and my toddler was running around yelling and we're trying to keep him under control and my daughter was yelling.” “I was just sweating, and I lost it. I knew everybody was staring at me, and I didn't realize how loud I was yelling at my kids and my wife grabbed me and told me to go outside.”

I now feel so much more comfortable because I know it's not going to get to that point because I know if I don't catch it in time, this dog is going to catch it before my wife catches it, and we're going to handle it before it gets to that point.

One participant described how having the SD helped him get through some of the rough times, and enabled him to bounce back from symptoms quicker. A few other participants explained that having the dog allowed them to go out more, and do things they wouldn't normally do, like sit on a board, take a new job, participate in a race, or do a speaking engagement. However, participants described how they focused more on whether a destination was appropriate for their dog, and they moved at a slower more relaxed pace with their SD.

It's different. And then on the other side, as far as the depression and things, it's significantly better. My wife and I discussed this about a month ago… She was worried, knowing how the lockdown, and how the last eight months have gone, she said she was nervous at the thought of not having [de‐identified dog]. She's like, “Having him, I can see you still have things that you work through, but you bounce back a whole lot quicker.”

Just yesterday, we took the kids to the big pumpkin patch place. It changes … You get [de‐identified dog] out of the car, you put his vest on, you walk at … He's not running out in front of you. You walk at his pace. He walks at my pace. The kids walk at his pace.

I feel like there's a lot of things I wouldn't have done if I didn't have her.

Participants also described challenges with reintegration including not having a peer group or feeling like they had anything in common to talk to other civilians about. This was especially prominent with the female participants.

And I didn't have any peers. I was 46 years old; I had been in the military for 27 years. There's not that many women to begin with and there weren't that many women of my rank and all of a sudden you throw me into civilian society where an average woman who was 46 years old probably had her career or she raised a family, or she cooked, or she had these nice, wonderful hobbies of which I knew nothing about. I so missed that whole female indoctrination. “I'm not trying to be gender insensitive here but going out for coffee with three females was the most terrifying thing anybody had ever asked me to do because I thought, “I don't have anything worthy to talk about.””

You've really got an effort to make civilian friends and you've got to make an effort to understand the civilian world and why people don't line up in lines correctly. And you do get to just say, “Okay, you've been dropped in Mars, and you've got to adjust because Mars is not going to adjust to you.”

Overall, participants reported increased socialization, and a greater desire and ability to be around people in public situations. These public situations ranged from being in large crowds, daily tasks such as going to the grocery store and running errands, to being able to have friends over for dinner and taking vacations with family.

Many participants explained that having their SD helped to increase their verbal interaction with others in social settings. Prior to being paired with their SD, many participants described being avoidant and not initiating or continuing conversations with others.

I'd say, it's gotten better. I mean, before I got her, I wasn't very, I don't want to say talkative, but I was more inclined to avoid people. I'd just do the bare minimum out in public, I was never rude or anything, but I wouldn't strike up a conversation with a stranger. But now, it's like an everyday occurrence, because just everyone who sees or feels the need to tell me about dogs they've had in their lives.

Participants also described their SD as a tool that helped to maintain their functional status. The SD helped to refocus them away from their symptoms, and also provided the participants with an exit strategy when a social situation became too much for them.

I think with her the biggest thing is there's something else to focus on, instead of automatically going, “Well, this place is too busy,” or “This place is too loud.” I can more focus on her than by my panic mode.

The primary theme SD included the subthemes Relationship with SD, Support, Impact of SD, and Advice and Recommendations. Participants described the bond they had with their SD as extremely strong, and expressed full confidence in their dog's ability to be intuitive, attentive to their needs, and respond to their symptoms. One participant explained the relationship with their SD helped ease the transition and feelings of loneliness from leaving the military and part of something bigger, to civilian life. Participants described their SD as a large source of support, and feeling that everything was going to be all right because their SD was physically there.

So that degree of touch, the tactility of that keeps me grounded, keeps me sound of mind and strong with spirit.

Participants explained the profound impact their SD had on their treatment regimen, and their lives. Some even credited the SD with giving them a reason to live and the fact that they were still alive, describing the SD as making them less likely to commit suicide.

I would say in 95% of cases, that's one less person who's going to commit suicide.

A few participants described having a decrease in symptoms, such as panic attacks since being paired with their SD. Additionally, one participant discussed his SD providing him with a positive outlook and being a source of motivation.

I'm not going into any… I can't think of a single full blown panic attack I've had, since I've had him.

It's definitely for the better. He cheers me up, he brightens my day, he encourages me to go out there and live life. I feel… He's there for me if there's something I want to do, like go and play that disc golf tournament…

A few participants emphatically explained that their SD was a not a pet, but that they functioned almost as a piece of medical equipment. Participants described how they and their SD had gotten used to each other, which helped the participants do things they wouldn't normally do. Some participants discussed how their SD was always watching them, and often realized the participant wasn't feeling well before the veteran did. One participant explained that their SD was also trained as a hearing ability dog.

What's interesting is I didn't notice it until people started pointing it out, but his eyes never leave you. He's always watching to see where you are.

And he is two and a half years old. And he's a rockstar, he does everything that [the other dog] does and then they even tweaked some things where if [my husband] calls my name from anywhere outside or wherever, [the dog] alerts me that [my husband]'s calling my name. And I could turn around and go find him or he takes me to where [my husband] is. We call him the marriage saver. Because living with a deaf person…

Barriers and Challenges

Many participants described wanting to share their experiences with other veterans. Participants explained that not everyone needs a SD and stressed the importance of realizing it is a big commitment. However, participants felt while having a SD is a large responsibility it is worth it if they really wanted to change. Participants discussed the importance of matching the veteran with a SD based on their personality and lifestyle needs and advised SD organizations to stay in contact with veterans after pairing them with a SD.

The theme Barriers and Challenges was comprised of the subthemes Cost, Public Perception, Acquisition Process, and Training. Participants described barriers and challenges they faced in utilizing their SD.

All of the veterans received their dog at no personal cost through nonprofit organizations. Veterans with a physical disability had their SD's care covered by the VA. However, at the time of this study, if a veteran did not have a physical disability the veteran was responsible for the cost of maintaining the SD. Participants acknowledged the range in cost of training their SD between $25,000 and $60,000. Participants expressed feeling truly fortunate to have been the recipient of their SD, as the cost of acquiring the SD would have been prohibitive if they had been responsible for it.

Some participants explained their frustration with people who did not understand what a service animal does. Participants described a general lack of knowledge regarding the purpose and function of a SD; that the SD is not a pet, but a working service animal. Participants reported the general public would come up and touch the SD without asking, interfere with training, approach the SD when working, distract the SD, and bring other untrained dogs over to the SD. Participants discussed that these all can create potentially unsafe situations. Additional challenges included SDs not being allowed in housing, lack of resources, and pressure to represent veterans and SDs positively. Occupational challenges included employer resistance, the SD not being allowed in different environments, and concern about colleagues' perception of the veteran after being paired with the SD. Additionally, participants reported that untrained SDs with inappropriate or unsafe behavior made some situations harder for actually trained SDs.

I think it's education about what service dogs really do and why they're important to people who have service dogs, they're not a pet, we're not trying to get over on anything by having a service dog. We need these service dogs to perform tasks for us so that we can live our life with independence and with dignity.

There was that kind of social thing. Everybody had to try to figure out if they had to treat me differently all of a sudden. Like, “Well, are you okay?” I'm the same guy I was last week, you just now know there's a dash 10 code that goes with my diagnosis as opposed to the guy the week before.

“I would encourage there to be some advocacy from providers. I think there should be less of a stigma or maybe should be education about service dogs, that it's a different alternative treatment.” That maybe this is a medical device. This is a durable medical piece of equipment kind of deal. And viewing them as that as opposed to, like we talked about earlier, the other stigma of this is a dog. No, this is a service animal. And actually, we won't refer to her as… She's not a dog, she's a service animal. She might look like a dog, but she's a trained service thing.

Acquisition Process

Participants described diversity in the acquisition process. One participant felt they just met the right people at right time; another participant explained that another veteran who had an SD recommended that they apply for one. Another participant reported their doctor recommended they apply for an SD after their medications were having negative side effects. Participants reported that they were paired with an SD who matched their lifestyle, needs, and personality.

Participants' experiences varied greatly with acquiring their SD. Some reported a lack of resources and had challenges getting an SD when they felt they needed one. Additionally, participants discussed it was a prolonged process, and they had a difficult time finding out about organizations that trained and provided SDs. One participant explained how they emailed an SD organization directly.

I think if someone's open to the option of getting one, they should be able to get one a lot easier than the hoops you have to jump through.

And so, it was like a hope and a prayer, I guess, for lack of a better term. And so, I continued to sit on my computer, and I got on Facebook and was messing around. And then all of a sudden, I got a return email and in the subject line it said, “America's VetDogs.” And I took a really deep breath because I thought, “Man, if they say no to me, I don't know what the next step is.” And so, I open it up and there was one work in that email, and it was the word, “Yes.” That's all they said was yes.

Another participant was told about an opportunity to get a SD by their counselor and felt the process was smooth and quick and thorough.

Right, and I'll tell you he was so jealous when I got back with [de‐identified dog] and all the help I had and all the support I had. He's asking me questions because he didn't get that training with his service dog like we get from Leashes of Valor.

Training

Participants described the tasks their SDs were trained to execute, such as putting their paw on the participant's foot if it was tapping, licking their face, nightmare interruption, and blocking, that is, the unconscious repression of unpleasant emotions, impulses, memories and thoughts from the conscious mind. Few participants explained how their SD adapted to their environment and their individual needs. Often, the participants would describe the SD making them realize they were starting to not feel well.

But he's trained to recognize, I guess, my little tell‐tale signs of when I'm starting to become anxious, or go to a darker place, and alert me and bring me out of it.

Participants discussed the need to maintain their SD's skills by regularly practicing them, and understanding that if the skills weren't practiced, they wouldn't stay sharp.

Lack of practical training. You train as you fight, you will fight as you train. When you slack off on the training, they begin to slack as well. Because I'm not out working at the level that I was before, and I have to make a very conscious effort to keep him fresh. I got to go through some exercises, got to do some training, got to do bottom puzzle just to keep his brain working. I have to put him on a leash and walk him in and out of stores or else you lose that skillset. The military folks would understand it as a perishable skill.

One participant described how incredibly intuitive his SD was, and how he was often sensitive to others in his veteran's immediate environment.

I had one guy … Seriously, I watched him walk off of a stage one time and go put his head in the lap of somebody in the front row and I actually stopped the speech and I'm like, “Hey, man. I'm sorry.” He's like, “I'm good” and he's just petting the dog. Afterwards, the guy comes up and he's like, “Sorry for hijacking your dog.” I'm like, “No worries. What do you got going on in your life?” He goes, “What do you mean?” I go, “He wouldn't do that if he didn't sense something's going on.” The guy started crying. He says, “I lost my mom two days ago.” I go, “That's his gift.” I don't know how the trainers encouraged that or figured that one out, but they did with him and he's the perfect animal for the life that I've been given.

Participants described their SDs' training programs as lasting between one and one‐half to 2 years of training prior to an in‐person residential training program to pair the SD with the veteran, lasting approximately 2 weeks. However, one participant described the inconsistency in highly trained SDs and those who claim to be trained, but never actually were.

The challenge lies in the fact that there are some that order papers off the internet where they try to train their own dog to become a service dog. That usually doesn't work. Also, as a senior executive in the VA, I found repeatedly I had troubles with service dogs that were not appropriate for the medical, for any environment. I had to have my police remove some of these dogs from the premises and their owners, of course, because they were barking, and they were biting and defecating and other things that just don't happen…

DISCUSSION

Veterans faced a multitude of complex challenges in managing their PTSD and/or TBI diagnoses while utilizing an SD as a therapeutic modality. While significant challenges were present, participants described enormous contribution to functional status and overall well‐being while utilizing their SDs. In a qualitative study conducted by (

30) researchers reported the benefits of SD therapy in veterans with PTSD as improving sleep quality and reducing hypervigilance. Some of the challenges were related to the need to prepare veterans for the responsibilities of caring for an SD. Veterans also reported that the community response to the SD was overwhelming as dogs drew unwanted attention to the veterans. Our research noted similar themes related to the benefits and barriers of working with a SD. (

31) explored the effects of SDs on veterans with PTSD. Their research compared veterans with an SD (

n = 75) and veterans who were provided usual care (

n = 66) for PTSD. The primary outcome was a longitudinal change on

The PTSD Checklist with secondary outcomes including differences in depression, quality of life, and social and work functioning. Key findings revealed clinically significant reductions in PTSD symptoms from baseline following the receipt of a SD, but not with usual care alone. The addition of trained SD to usual care may confer clinically meaningful improvements in PTSD symptomology although not a cure for PTSD. The respondents in our research attested to the fact that the SD decreased their anxiety and panic attacks but all participants in our study had a SD, so we did not have a comparison group.

Our research also focused on both PTSD and TBI, whereas most studies focused on PTSD only.

Our study adds to the body of knowledge related to the benefits and barriers to using SDs as a tertiary treatment modality for veterans with PTSD and/or TBI. Further research needs to be conducted in this area during this 5‐year window to continue the funding provided by the PAWS (

32) Act that supports SDs as an adjunct treatment modality for veterans' suffering from PTSD.

Limitations

The participants in this qualitative study were 100% white, were all married and living with spouses, and the sample size was small with 10 participants. Consideration of diverse ethnic groups and veterans living alone or in homeless shelters would be important to explore. The mean years to post discharge from the service was 8.3 years and it is unknown if the participants were treated with medication and/or counseling in addition to the SD.

Implications for Future Research

The participants were from 0 to 15 years post deployment. A study conducted with veterans who were one to 2 years post deployment and were provided with a SD to manage the effects of PTSD and/or TBI, would strengthen the findings of this research study. It would also be important to explore the effects of medication and/or counseling prior to and after the addition of a SD to quantify the benefits of a SD as an adjunct treatment modality for PTSD and/or TBI. Research with participants who are racially and ethnically diverse, living alone, or homeless would be important to explore as these demographics put veterans into another risk category. Additionally, it is important to address the reintegration challenges female veterans face post deployment.

CONCLUSION

The most prominent theme in this study was “functional status.” The SDs provided veterans the support they needed to reintegrate into civilian life. The veteran participants in this study articulated the benefits of having a SD as a treatment adjunct to managing their PTSD and/or TBI. They reported an increase in social activity outside of the home, more interaction with family and friends, and a decrease in the need for medication. The research participants discussed the abilities of the SD to pick up on behavioral cues related to anxiety, a warning sign of an impending panic attack and possibly suicidal ideations. The barriers identified were lack of resources from the time of diagnosis to acquiring a SD with a span of 0 to 15 years post deployment. The cost to train one SD is approximately $25,000.00.

Reintegration into civilian life by veterans' post deployment is incredibly challenging. Veterans, by nature of their culture and the stigma attached to mental health disorders such as PTSD and TBI, oftentimes do not seek professional help. This qualitative research supports the use of SDs who are trained to mitigate the negative effects of PTSD and TBI in veterans post deployment regardless of having a concomitant physical disability. As noted by one study participant: “He's the reason I am still alive.”