Despite the high prevalence (

1) and impact of mental and substance use disorders (

2), there remains a significant problem accessing treatment (

3,

4). There are several possible explanations for why treatment of substance abuse and mental disorders is delayed or avoided.

One likely factor is a shortage of mental health providers. Thomas and colleagues (

5) estimated that only 4% of counties in the United States have adequate availability of mental health professionals. Further, mental health providers are unevenly distributed across the country. Rural areas, in particular, have had very high levels of unmet need for behavioral health services for decades, largely because of challenges associated with recruitment and retention of mental health professionals.

Mental health professionals with the specialized skill mix required to provide psychotherapy and prescriptive management to individuals seeking mental health services are in short supply (

6). Psychiatrists and psychiatric mental health-advanced practice registered nurses (PMH-APRNs) are the main providers of these services nationwide, although clinical psychologists have limited prescriptive authority in two states (

6).

The workforce shortage is particularly acute among professionals who are credentialed to provide behavioral health treatment to children. Child and adolescent psychiatrists (

7) and PMH-APRNs are educated to provide both psychotherapy and prescriptive management for children and adolescents. Currently, however, there are fewer than 7,500 child and adolescent psychiatrists and 1,750 PMH-APRNs at the certification levels of child or adolescent clinical nurse specialist and family nurse practitioner (

7) for the whole country, despite estimates that 13% of children in the United States have a mental illness (

8).

PMH-APRNs have been effectively providing mental health treatment (

9), but the extent of their authority to prescribe medication and whether their prescriptive management must be supervised by a physician varies by state. There have been, however, persistent calls for uniform advanced nursing practice across the country and the removal of barriers to full scope of practice, including limits on independent prescriptive practice (

10,

11).

Given the expanding scope of practice by PMH-APRNs and the cost-effectiveness of their services, it will be helpful to have a clear understanding of their geographic location in order to direct future advanced practice nursing education, clinical practice, and public policy initiatives. Although Thomas and others (

5) included PMH-APRNs in their analysis, the location of and estimates of shortages of PMH-APRNs were not provided (

5).

This article describes in more detail the geographic distribution of PMH-APRNs in the United States by using Geographic Information System (GIS) techniques. The objectives are to identify geographic regions with shortages of PMH-APRNs, describe rural-urban differences in the distribution, and discuss implications of the geographic distribution.

Methods

The data source was a complete listing, provided by the American Nurses Credentialing Center, of the employment zip codes of certified PMH-APRNs during 2007 (N=10,452). By using GIS techniques, we completed a geographical analysis of the distribution of PMH-APRNs.

GIS is an information system that stores, manipulates, visualizes, and analyzes data that are linked to geographic locations. In this study, GIS functions were used to identify the pattern of distribution of PMH-APRNs in a two-step methodology. In step 1, U.S. Census zip code data were used to aggregate the certified PMH-APRN data set at the county level to facilitate better visualization and mapping of certified PMH-APRNs.

In step 2, a cluster analysis was conducted with the hot-spot analysis tool in ArcGIS 9.3.1 to identify geographic regions with shortages of PMH-APRNs. The hot-spot tool identifies spatial clusters of variables with statistically significant high or low values. Given a weighted variable—in this case, population-weighted PMH-APRNs—and operating under the assumption that data values are randomly distributed across the study area, this tool delineated clusters of counties with higher than expected numbers of PMH-APRNs. These clusters, called hot spots, were counties with significantly higher availability of advanced practice nurses. The tool also delineated spatial clusters of lower than expected numbers of PMH-APRNs. These clusters, called cold spots, were counties with significantly low availability of advanced practice nurses.

The hot-spot analysis also produced z scores and p values, which were used to confirm whether the findings were statistically significant. Very high or very low z scores associated with p values less than .05 were indicators of statistically significant hot and cold spots, respectively.

Results

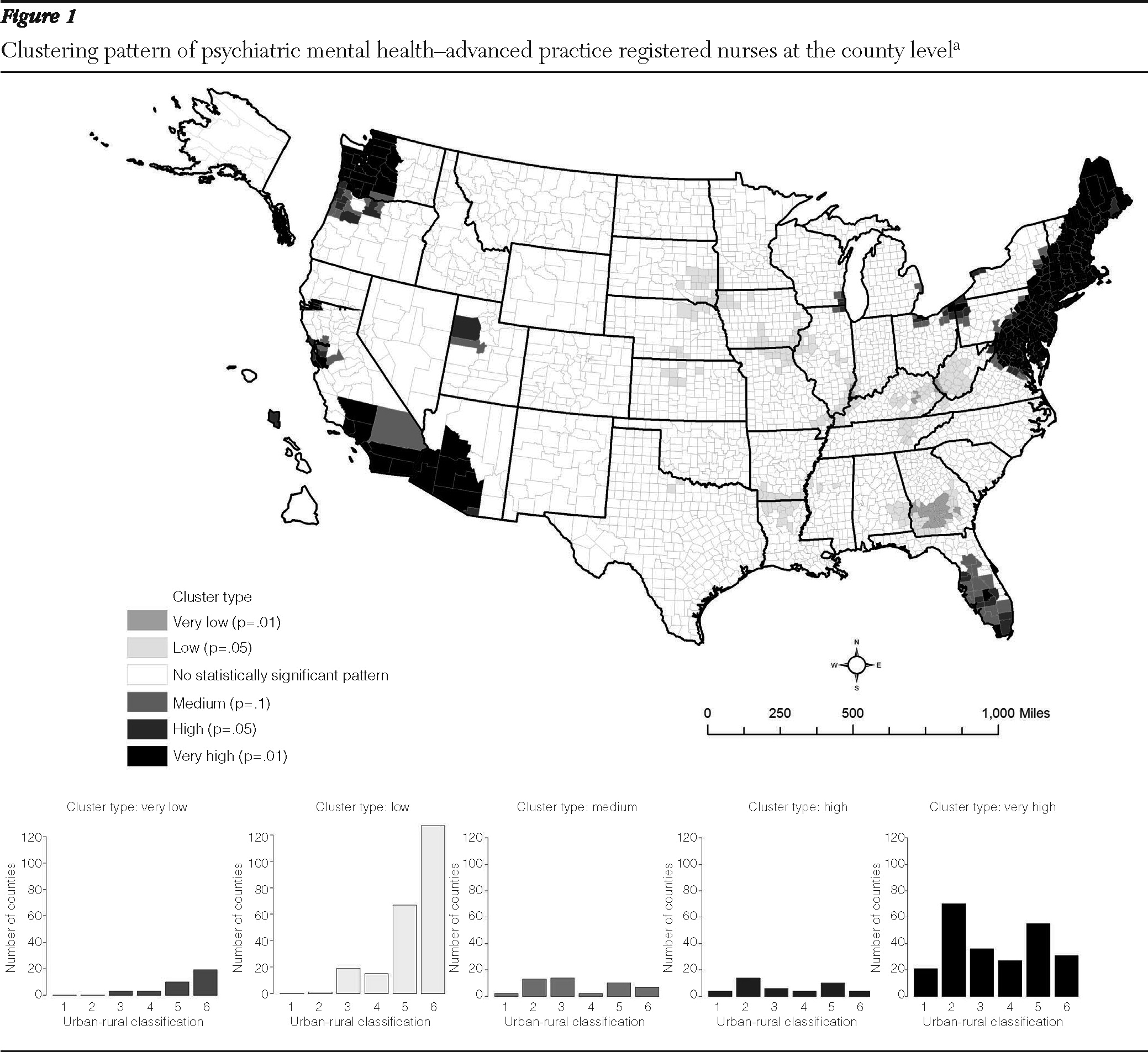

Concentrations of high numbers of PHM-APRNs, or hot spots, were found in the northeastern United States, parts of northeast Ohio, western Washington, southern California, and parts of Florida. Significant scarcities of PMH-APRNs, or cold spots, were seen in the Midwest (

Figure 1). [A full-color version of the figure is available in an online appendix to this report at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

The cluster analysis also determined the rural-urban differential of the distribution of PMH-APRNs to ascertain whether the shortage of PMH-APRNs was in the rural areas. Counties were divided into six urban-rural categories on the basis of the 2006 National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) classification scheme. NCHS data systems are often used to study the association between urbanization level of residence and health and to monitor the health of urban and rural residents. The 3,141 U.S. counties are classified from most urban to most rural; the most urban were large counties with one central metropolitan area (population one million or more), followed by large fringe metropolitan (population one million or more), medium metropolitan (population 250,000 to less than one million), small metropolitan (population 50,000 to 249,999), rural, and rural noncore counties.

Histograms depicted in

Figure 1 show the urban-rural classification of the counties by clusters of PMH-APRNs. Counties characterized by very low or low cluster types (cold spots) had significantly higher number of rural counties (N=150), evidence of the scarcity of PMH-APRNs in the rural areas. On the other hand, counties characterized by very high cluster types (hot spots) showed higher numbers of counties belonging to the large central metropolitan group (N=35) and large fringe metropolitan group (N=80). This finding further emphasized the uneven distribution of PMH-APRNs among urban and rural counties.

Discussion

Given their educational preparation in both psychotherapy and prescriptive practice, PMH-APRNs could play a significant role in the provision of mental health services, especially as more people become eligible for care during the rollout of mental health parity and general health care reform. The potential contribution of this segment of the mental health workforce, however, is limited by the uneven distribution of PMH-APRNs across the country. Significantly more PMH-APRNs provided service in the northeastern United States than in Alabama, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and the Appalachian region, where their numbers were very low. In addition, significantly fewer PMH-APRNs were employed in rural versus urban areas.

These findings extended the work of Thomas and others (

5) by highlighting the regions with scarcity of PMH-APRNs. However, the results of our analyses were limited, primarily, by the nature of the data available. Only one national body provides certification for PMH-APRNs, although many nurses obtain certification to qualify for Medicare and other national insurance. California, Indiana, Kansas, Nevada, New York, and Oregon do not require national certification for recognition as a PMH-APRN (

12). Therefore, the total number and location of PMH APRNs in those states were not easily determined. Additionally, our estimates of shortages of PMH-APRNs by population did not account for the likely uneven distribution of mental illness across the country. However, none of the areas included in the analysis of the weighted sample were located in cold spots, an indication that mental illness was not underrepresented

Our findings have implications for the education and practice of PMH-APRNs and for public policy that will enable workforce development. Of the six core mental health professional disciplines, PMH-APRNs are the fewest in number, followed in order of increasing numbers by psychiatrists, marriage and family therapists, psychologists, licensed professional counselors, and social workers (

5). Given the skill set of PMH-APRNs, disparities in access to mental health services can, in part, be most obviously addressed by increasing the number of applicants to PMH-APRN educational programs.

A number of actions could facilitate an increase in applicants to PMH-APRN programs, including the development of additional graduate programs, extension of existing program offerings into rural areas, collaboration by universities to share resources, and intensified recruitment of registered nurses into psychiatric mental health graduate programs, especially from areas with low distribution. Financial support to graduate students during their program of study could be increased, and PMH-APRNs could be prepared to provide care across the lifespan to meet a current shortage in children's services and the expected increase in mental health needs as the elderly population grows.

Our findings provide further support for the reduction of barriers to the full scope of practice among PMH-APRNs. In fact, existing PMH-APRNs already have the educational preparation to assume this level of care. This effort can be promoted by aggressively providing education about the practice potential of PMH-APRNs to state legislators, third-party payers, mental health providers in other disciplines, and prospective employers.

Conclusions

Geographical and statistical analyses highlighted an uneven distribution of PMH-APRNs, professionals who represent a small but highly skilled segment of the mental health workforce. Our findings provide further evidence of the need to boost the numbers of PMH-APRN graduates, increase incentives to locate programs to educate and employ PMH-APRNs in underserved areas, maximize the potential of APRNs to prescribe, and eliminate barriers to PMH-APRN practice in order to expand access to mental health care.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank the American Nurses Credentialing Center for providing the data for this study.

The authors report no competing interests.