People experiencing or perceived to have a mental illness are often subject to negative stereotyping and biases (stigma) from many sources, producing multifaceted negative effects (

1–

3). Such individuals frequently suffer additional harm as a result of internalized stigma (

4). “Internalized” stigma or “self-stigma” occurs when a person cognitively or emotionally absorbs stigmatizing assumptions and stereotypes about mental illness and comes to believe and apply them to him- or herself (

5–

7). Internalized stigma has been associated with a number of negative outcomes, including increased depression, avoidant coping (

8,

9), and social avoidance (

10); decreased hope and self-esteem (

10); worsening psychiatric symptoms (

11); and decreased persistence in accessing mental health services and other supports (

12).

In turn, these negative self-concepts and ineffective coping strategies can hinder illness management (

5,

8) and impede individuals’ pursuit and achievement of their recovery goals (

9). Therefore, a movement is emerging to identify ways to help individuals with mental health problems reduce or avoid self-stigma (

13–

16). However, the prevalence of internalized stigma among adults with mental illnesses, its effects on psychosocial outcomes, and the corresponding patterns of relationships between internalized stigma and these outcomes have not yet been fully explored.

Understanding how internalized stigma develops, how it is maintained, and how it interacts with other psychological and behavioral processes is important for identifying and developing interventions to reduce internalized stigma. Although a number of studies have identified individual relationships between internalized stigma and other indices of psychosocial functioning, few have attempted to examine the pathways by which mental illness–based discrimination leads to psychiatric symptoms.

Muñoz and colleagues (

17) tested a multivariable model based in part on the social-cognitive model of self-stigma (

18). This model posits that people with serious mental illness internalize negative messages via a series of cognitive processes: stereotype awareness, stereotype agreement, and self-concurrence (

19,

20). Stereotype awareness occurs when an individual is exposed to and becomes aware of the negative societal stereotypes about mental illness. Subsequently, the individual decides, tacitly or deliberately, whether he or she agrees or disagrees with the assumptions. Stereotype agreement occurs when an individual accepts the stereotypes as true and valid. The stereotypes then become personally relevant when the individual develops mental health problems, begins to identify him- or herself as someone with a mental illness, and receives a mental illness diagnosis or services. If the individual agrees that these stereotypes are true and comes to believe that they apply to him- or herself, “self-concurrence” occurs, leading to internalized stigma. In turn, internalized stigma can then lead to a number of negative consequences, including poor self-esteem, reduced self-efficacy, more impaired social functioning (

10), and greater psychiatric symptoms, including depression (

8,

11).

Results from Muñoz and colleagues’ study (

17) supported aspects of this model, including that stigmatizing beliefs and discrimination experiences are associated with recovery orientation and internalized stigma, which both influence psychosocial functioning. However, this model did not include two key concepts central to the social-cognitive model, self-concept (such as self-esteem and self-efficacy) and psychiatric symptoms, which have been shown to be associated with self-stigma (

18–

20). We conducted a survey of a convenience sample of individuals receiving mental health services in order to further examine the prevalence of internalized stigma and its correlation with demographic, clinical, and recovery-related variables and to construct and test a hypothesized model of their interrelationships.

Methods

Participants and procedures

One hundred individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depression were recruited from three community outpatient mental health programs and one Veterans Affairs medical center in Maryland. Participants were between ages 18 and 80 and were receiving mental health services at one of these sites, were deemed clinically stable enough to participate by a mental health provider, and were able to provide informed consent. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the VA Maryland Health Care System.

Participants were recruited through flyers posted at the participating clinics, announcements during clinic groups and meetings, and clinician referrals. All individuals who expressed interest in participating were screened to confirm that they were eligible to participate. Eligible individuals who consented to participate completed an interview lasting approximately 45–60 minutes. Of the 107 individuals screened, 103 (96%) were determined eligible. Of the four who were not, three were ineligible because they could not be reached for an appointment and one had a health problem preventing participation. Of the 103 eligible, three declined to participate, leaving a total of 100 participants. Most participants (N=91) were recruited from the community mental health programs.

Measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

Self-reported demographic characteristics were collected from each participant. Primary psychiatric diagnosis was obtained from the participant’s clinical chart or current mental health provider. Symptom severity was measured with three subscales from the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), a self-report instrument measuring degree of distress from various symptoms over the past week (

21): anxiety, depression, and psychoticism. Possible scores for the subscales range from 0 to 4. In each case, higher scores represent greater symptom severity.

Internalized stigma.

Individuals’ subjective experience of internalized stigma was measured on the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (ISMI) (

13). In addition to producing an overall score, the ISMI contains five subscales: alienation, stereotype endorsement, discrimination experience, social withdrawal, and stigma resistance. The alienation subscale is a measure of the subjective experience of being less than a full member of society. The stereotype endorsement subscale measures the degree to which the respondent agrees with common stereotypes about people with mental illness. The discrimination experience subscale measures the respondent’s perception of current treatment by others. The social withdrawal subscale measures avoidance of social situations because of mental illness. And the stigma resistance subscale is a reverse-scored measure of the experience of not being affected by internalized stigma. Both the total and subscale scores are calculated as a mean, with possible total and subscale scores ranging from 1 to 4 and larger scores indicating greater self-stigma.

We also created a categorical variable to identify individuals with moderate to severe internalized stigma, defined as a total ISMI score of greater than 2.5, and mild internalized stigma, defined as a score between 2.0 and 2.5 (

8).

Recovery-related variables.

Sherer’s General Self-Efficacy Scale (SES) was used to measure self-reported self-efficacy, defined as a person’s beliefs or expectations about his or her abilities (

22,

23). Possible scores range from 17 to 85, with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) assesses self-esteem on a scale from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem (

24). Recovery orientation was assessed with the Mental Health Recovery Measure (MHRM) (

25), a self-report measure of the recovery process for individuals with serious mental Illness. The total score ranges from 0 to 120, with higher scores indicating stronger recovery orientation.

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics.

Demographic characteristics, psychiatric diagnoses, symptom severity, internalized stigma, and recovery-related measures were summarized by using percentages, means, and standard deviations as appropriate. We used Pearson’s correlations for continuous variables and one-way analysis of variance for categorical variables to examine relationships between internalized stigma, demographic and clinical characteristics, and recovery-related variables.

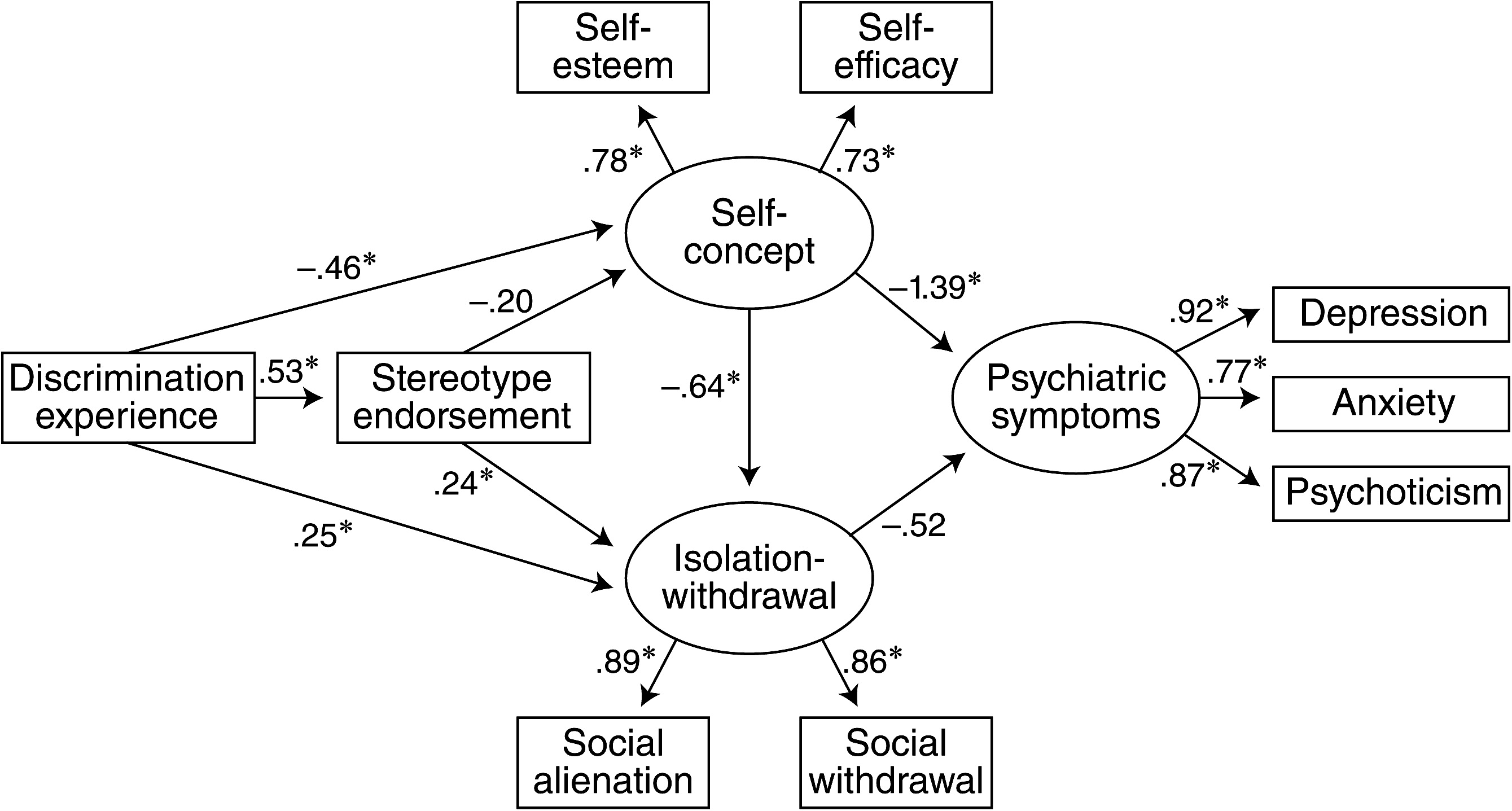

Structural equation model.

A structural equation model (SEM) was developed with Amos 16.0 (

26) to validate a hypothesized pattern of relationships among manifest and latent variables leading from mental illness–based discrimination to psychiatric symptomatology. For this analysis we hypothesized that discrimination experiences are directly and positively related to endorsement of stereotypes about people with mental illness. As individuals come to believe these stereotypes, they become internalized, a process that has a direct, negative effect on self-concept and leads to greater isolation and withdrawal. We hypothesized that discrimination is also directly related to a more negative self-concept and to greater isolation and withdrawal; as the self-concept of people with serious mental illness declines, the more isolated they become. Lowered self-concept and increased isolation-withdrawal then feed into greater severity of psychiatric symptoms. Although our data are cross-sectional, we sought to determine whether they are consistent with this model.

Manifest variables in the model were discrimination experience (ISMI), stereotype endorsement (ISMI), self-esteem (RSES), self-efficacy (SES), social alienation (ISMI), social withdrawal (ISMI), depression (BSI), anxiety (BSI), and psychotic symptoms (BSI). The three latent constructs in the model were self-concept (comprising self-esteem and self-efficacy), isolation-withdrawal (comprising social isolation and social withdrawal), and psychiatric symptoms (comprising anxiety, depression, and psychotic symptoms). Model fit was assessed with multiple fit statistics, including the goodness-of-fit chi square test, the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants are summarized in

Table 1. Forty-two percent of participants had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 34% bipolar disorder, and 24% depression with or without psychotic features. Consistent with the population receiving services at these sites, a majority of participants were African American (83%), had never been married (71%), and had received a high school education or higher (57%). The mean±SD age of participants was 45.6±9.2. Overall psychiatric symptom scores (BSI) ranged from 0 to about 3 (from “none” to “quite a bit,” respectively), with a mean±SE score of 1.4±.8.

Internalized stigma and its relationship with other variables

The mean total ISMI score was 2.3±.4. Mean subscale scores ranged from 2.1 to 2.9, with a mean of 2.1±.5 for the stereotype endorsement subscale, 2.5±.7 for the alienation subscale, 2.5±.6 for the discrimination experience and social withdrawal subscales, and 2.9±.5 for the stigma resistance subscale. Thirty-five percent of participants reported moderate to severe levels of internalized stigma. An additional 46% reported mild levels of internalized stigma.

Overall, internalized stigma was not associated with age, gender, employment, marital status, or education. However, internalized stigma was significantly associated with greater symptom severity (r=.56, p≤.001), both overall and for each ISMI subscale, but did not differ by psychiatric diagnosis. Internalized stigma was also associated with lower self-esteem (r=–.56, p≤.001), self-efficacy (r=–.63, p≤.001), and recovery orientation (r=–.54, p≤.001).

Relationship between ISMI subscales and key variables

Table 2 shows correlations between key clinical and recovery-related variables and the ISMI subscales. Each of the variables in this table was included in the model.

Main structural equation model

The path diagram with factor loadings (standard regression weights) appears in

Figure 1. All observed variables (ovals in figure) were found to be good indicators of their latent factors (weights ranged from .73 to .92, all p values <.001).

As hypothesized, discrimination experience was significantly associated with stereotype endorsement and isolation-withdrawal in this sample, indicating that participants who had experienced a high level of discrimination tended to endorse high levels of stereotypes about mental illness and tended to engage in a high level of isolation and withdrawal. More discrimination experience was also associated with self-concept, in that participants who had experienced a high level of discrimination tended to have lower self-concept. Self-concept in turn predicted isolation-withdrawal, indicating that participants with lower self-concept tended to engage in a high level of isolation and withdrawal. Stereotype endorsement was not significantly associated with self-concept, nor did isolation-withdrawal predict psychiatric symptoms (as hypothesized) (p>.05).

The goodness-of-fit test was nonsignificant, supporting the fit between our hypothesized model and the data. Other fit statistics (GFI=.96, RMSEA=.011) provided strong support for model fit.

Exploratory models

Several exploratory models that included recovery orientation (MHRM) as both a manifest and latent variable (along with self-efficacy and self-esteem) and the ISMI stigma resistance score as a manifest variable were tested to examine whether recovery orientation and stigma resistance would buffer the effects of discrimination experience on the other social and psychological variables. However, regardless of where these variables were placed, the resulting model fit was poor. In addition, both recovery orientation and stigma resistance were run in independent moderation models (

27), and neither was found to statistically moderate the relationship between discrimination experience and stereotype endorsement.

Discussion

In line with previous research (

4,

8,

28), we found that a substantial number of people with serious mental illness reported experiencing internalized stigma. Over one-third of participants reported moderate to severe levels, and an additional 46% reported mild self-stigma. Internalized stigma was associated with a number of negative outcomes, including lower self-esteem, self-efficacy, and recovery orientation, as well as greater psychiatric distress. Although two-thirds of the sample did not feel highly stigmatized, the strength of these relationships in the data coupled with the fact that most participants reported lower levels of internalized stigma suggests that internalized stigma may be detrimental even in minimal amounts. These findings highlight the need for mental health providers to discuss internalized stigma and its impact with their clients, to discuss strategies and tools that clients currently use to minimize self-stigma, and to develop interventions for its prevention and amelioration.

Internalized stigma was not significantly associated with any measured demographic and clinical characteristics (including age, gender, education, or diagnosis). Results from previous studies examining such relationships have been mixed. Some have found higher rates of internalized stigma among African Americans (

29–

31); others have not. However, the homogeneity of our sample prevented us from evaluating race associations. Similarly, some studies suggest greater internalized stigma among women (

4), persons with schizophrenia (

28,

32), and those ages 35 to 54 (

4), but others have not. These mixed findings suggest that relationships between these variables and internalized stigma may be complex. For example, people with multiple socially stigmatized identities may have to navigate a dynamic web of various types and sources of stigma and may have to weather additive or synergistic negative effects of multiple stigmatized identities, but they may also be able to develop interrelated coping and resilience resources (

29). Such variable findings may also highlight a need for more sophisticated measurement of the intrapersonal impact of internalized stigma, relevant demographic variables, and the types of internalized stigma that can be associated with various identities.

Identifying ways to reduce internalized stigma in regard to mental illness and minimize its negative effects requires understanding the processes by which it develops, is maintained, and leads to psychosocial outcomes. The SEM results in this study suggest several pathways through which stigma and discrimination experiences may contribute to psychiatric distress. In turn, these may suggest several avenues for intervention. As in the social-cognitive model (

17–

19), some individuals experiencing stigma or discrimination may accept stereotypes about people with mental illness as applying to themselves or believe that discrimination they experience is warranted (self-stigma), leading to demoralization, negative self-concept, and withdrawal, all of which can exacerbate psychiatric symptoms. Interventions could work to undermine the perceived accuracy of such stereotypes and their perceived self-relevance. As such, many of the tools and strategies used in cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies could be used to help individuals challenge the accuracy of and potentially change these self-stigmatizing beliefs. Similarly, helping individuals to broaden their self-concept beyond the illness, by identifying personal strengths, positive qualities, and values and ways to build upon and strengthen them, could serve to highlight and reinforce the inaccuracy of these stereotypes.

For other individuals, fear or concern of rejection by others, rather than actual self-stigma (believing and internalizing stereotypes), may be what leads to a poorer self-concept and disengagement from others (to avoid anticipated rejection), which may then lead to greater psychiatric symptoms. In this case, it may be more helpful to use interventions that assist people in realistically assessing the likelihood of rejection, by using cognitive and cognitive-behavioral strategies and helping individuals develop or strengthen connections with nonstigmatizing others. Thus interventions aimed at reducing self-stigma may want to target multiple points along these various pathways.

An interesting finding was that although recovery orientation (MHRM) and stigma resistance (ISMI) were significantly related to many of the variables in bivariate analyses, including them did not improve the fit or explanatory power of the SEM and, in fact, rendered each of the resulting models a poor fit. Similarly, neither variable statistically moderated the relationship between discrimination experience and stereotype endorsement. Internalized stigma may have such strong effects on psychosocial outcomes that it eclipses what would otherwise be the positive influence of an optimistic cognitive approach to recovery.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, it involved a largely African-American sample, with only a small percentage of participants of other racial backgrounds, which may limit its generalizability and precludes us from drawing any conclusions regarding internalized stigma and race-ethnicity. Similarly, the limited range of diagnoses among participants may have created a limitation for that variable. Additional studies using larger samples are needed to adequately examine these relationships. Second, this was a cross-sectional study, so we are unable to establish causal relationships between the variables. Research assessing individuals at several time points is needed to better understand the impact of internalized stigma on self-concept, community and social functioning, and aspects of recovery. Finally, the study examined the relationships among internalized stigma, self-concept, and psychiatric symptoms, and although reduction in clinical symptoms is an important variable for many mental health consumers, it is only one outcome. Thus the effect of internalized stigma on broader outcomes related to mental health recovery and quality of life also needs to be examined.

Conclusions

Internalized stigma is prevalent among individuals with serious mental illness and can have a negative impact on self-concept, social relationships and community involvement, and psychiatric health and well-being and may impede the recovery process for individuals with mental illness. However, there may be multiple pathways through which experiencing stigma and discrimination as a result of a mental illness may lead to these outcomes. Interventions aimed at addressing internalized stigma may require strategies that target multiple points along these pathways in order to be effective.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This article is the result of work supported by the VA Capitol Network (Veterans Integrated Service Network 5) Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

The authors report no competing interests.