Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been called the signature injury of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) (

1). It is estimated that nearly 20% of returning veterans have sustained at least a mild TBI during deployment (

2). In response, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) implemented mandatory TBI screening for all OEF/OIF veterans within the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system (

3).

TBI is defined as a physical force to the brain sufficient to cause structural alteration or physiological disruption of brain function that results in altered consciousness, amnesia, change in mental state, neurological deficits, or intracranial lesions (

2,

4). TBI is classified by severity of injury: mild, moderate, or severe. Mild TBI is the most common diagnosis among veterans who sustain a TBI (

5). TBI may result in cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physical dysfunction (

5).

TBI is associated with an increased relative risk for developing a psychiatric disorder (

5). One study found that over one-third of veterans with a history of TBI also had comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression (

6). Another study determined that combat-related mild TBI doubled the risk for PTSD (

7). Overlapping physical and psychological symptoms further complicate diagnosis and treatment of patients with comorbid PTSD and TBI.

Currently, there are no evidence-based guidelines for pharmacologic treatment of PTSD for patients who have a history of TBI. However, the research encourages using caution with medications that may impair cognition (

4,

8,

9). It is unknown if pharmacotherapies used in PTSD are beneficial or safe for veterans with comorbid mild TBI or affect their long-term outcomes (

1).

The purpose of this study was to determine if patients with PTSD and comorbid mild TBI are treated differently pharmacologically, have differences in adherence to or tolerance of pharmacologic treatment, or utilize more services than patients with PTSD alone. Differences in medication regimens, adherence, and service utilization may indicate that treatment benefit and ability to tolerate medications are affected by mild TBI.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort review of OEF/OIF veterans who were enrolled at the Lexington VA Medical Center (LVAMC) between April 1, 2007, and March 31, 2009, and who were ages 18 or older and had a diagnosis of PTSD. The study was approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board and the LVAMC Research and Development Committee.

Patients were identified by using the VA's Computerized Patient Record System and the VHA's Decision Support System databases. Patients with PTSD were identified from the database on the basis of

ICD-9 diagnosis codes. Because TBI is a diagnosis made at the time of the head injury, a TBI screening tool was used to identify OEF/OIF patients who warranted further evaluation to confirm the diagnosis (

3). Screenings were performed by nursing staff as veterans entered the health care system. TBI screening included four questions about history of events that may increase risk of TBI, symptoms of alterations of consciousness after the event, new TBI symptoms after the event, and continued TBI symptoms that remained at time of screen (

3). Answering yes to all four screening questions prompted further evaluation by a team of specialists who confirmed or rejected a diagnosis of mild TBI. Patients with PTSD who did not have a history of mild TBI were compared with patients with both a diagnosis of PTSD and a history of mild TBI. Patients were excluded from the study if there were no follow-up visits or medication claims after a diagnosis of PTSD was made. We hypothesized that pharmacotherapeutic regimens would differ for patients with PTSD and TBI and patients with PTSD alone. Therefore, the primary objective of the study was to determine if the pharmacotherapeutic regimen for PTSD was different when the PTSD was comorbid with mild TBI. Medication regimens were assessed by comparing the class or classes of psychiatric medications, total number of psychiatric medications, and defined daily dose (DDD) of psychotropic medications.

Medication regimens were evaluated for polypharmacy, defined as concomitant receipt of psychotropic medication in more than one of the following classes—antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, sedative-hypnotics, stimulants, and cholinesterase inhibitors. Doses of psychotropic medications were evaluated to determine if they were above or below the DDD. The DDD is an assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug when used for its main indication among adults (

10).

Secondary objectives of the study were to examine differences between the two groups in adherence, tolerance of medication, and utilization of services. Adherence was determined by using the medication possession ratio (MPR) in a six-month period. The MPR is defined as the total days supply of medication obtained divided by the corresponding number of calendar days (

11). Patients were considered adherent if the MPR was ≥.8. Medication tolerance was assessed by number of medication changes within a therapeutic class. Service utilization included number of all outpatient visits, mental health visits, and emergency room visits during the study period.

Outcomes were compared by using chi square analysis for categorical data and t tests for continuous data. A Wilcoxon's rank-sum test was used to compare nonparametric data. A logistic regression was performed to control for possible confounding variables (age, chronic pain, depression, headache, and substance abuse) between the groups. The significance level was set at .05, and all analyses were performed by using Stata, version 10.

Results

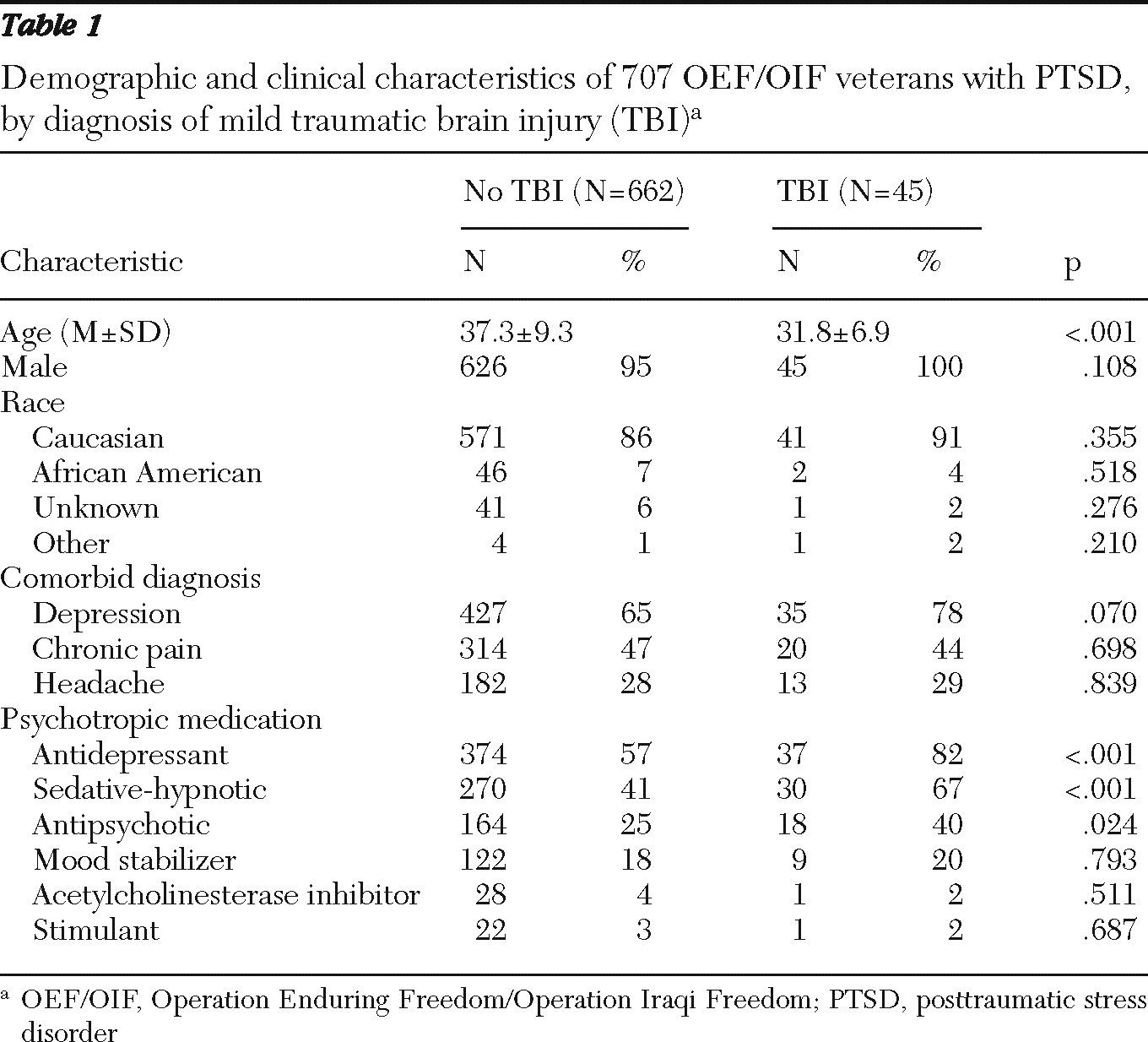

A total of 707 OEF/OIF veterans enrolled at LVAMC during the study period had a diagnosis of PTSD, and 45 (6%) also had a confirmed diagnosis of mild TBI. The groups were similar in demographic characteristics, but patients with PTSD and TBI were significantly younger (p<.001) (

Table 1).

A total of 82% of veterans with PTSD and TBI were prescribed an antidepressant compared with only 57% of veterans with PTSD alone (p<.001). The same trend was also seen with sedative-hypnotics, prescribed to 67% of veterans with PTSD and TBI and to 41% of veterans with PTSD alone (p<.001); and with antipsychotics, prescribed to 40% of veterans with both PTSD and TBI and to 25% of veterans with PTSD alone (p=.024). After adjustment for confounding variables, logistic regression showed that compared with the patients without TBI, the patients with TBI remained more likely to receive an antidepressant (odds ratio [OR]=2.9, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.3–6.5), an antipsychotic (OR=1.7, CI=.9–3.3), or a sedative-hypnotic (OR=2.5, CI=1.3–4.8).

Polypharmacy was more common among the patients with PTSD and TBI than among patients with PTSD alone. Thirty-two (71%) of the TBI patients and 307 (46%) of the PTSD-only patients were prescribed more than one psychotropic medication concomitantly (p=.001). Significantly more patients with TBI (N=24, 53%) than without TBI (N=244, 37%) received a psychotropic medication at a dose above the DDD (p=.028).

Medication tolerance for antidepressants, sedative-hypnotics, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers was similar between the groups. Statistical analysis for changes in medication for stimulants and cholinesterase inhibitors was not possible because medications from each of these therapeutic classes had been prescribed to only one patient in the PTSD and TBI group.

Adherence to psychotropic regimens was similar between the groups. Thirty-five (78%) patients with PTSD and TBI and 579 (88%) of patients with PTSD alone had an MPR ≥.8 for at least one psychotropic medication. The average MPR for all medications was .73 for the PTSD patients and .64 for the PTSD and TBI patients.

Total health care service utilization between the groups, as measured by mean±SD of visits during the study period, was not significantly different (28±25 in the PTSD and TBI group and 28±32 in the PTSD-alone group). However, the patients with PTSD and TBI had significantly more encounters with mental health clinics than did patients with PTSD only (9±11 versus 5±10, respectively; p<.001). The percentage of the group with emergency room visits was higher among PTSD patients with TBI (38%) than among those without TBI (28%), but the difference was not significant.

Discussion

To date, there is a dearth of evidence demonstrating the efficacy or tolerability of PTSD pharmacotherapy for patients with comorbid TBI. This study found significant differences in the use of drug therapy for veterans with PTSD and those with PTSD and TBI. Veterans with PTSD and mild TBI were more likely to receive psychotropic medications, use higher doses, and receive multiple classes of medications. These differences may be expected to have an impact on the outcomes associated with drug therapy for PTSD. Increasing dose and number of medications is often associated with poorer adherence, greater side effects, and reduced effectiveness in other chronic psychiatric conditions (

12).

PTSD has been associated with increased rates of treatment nonadherence (

13). The presence of mild TBI and any resulting cognitive impairment are expected to present additional challenges for medication adherence (

4,

8,

9). Our study did not find differences in medication adherence over a six-month period, although longer-term treatment may have generated a different result. TBI may also increase a patient's risk of experiencing side effects of psychotropic medications (

8). Surprisingly, we found that patients with PTSD and TBI were more likely than other patients to be prescribed a psychotropic medication at a dose above the DDD. However, tolerability, as measured by the number of changes in medications, did not differ for veterans with or without comorbid mild TBI, suggesting similar tolerance to psychotropic medication regimens in the study population. Moreover, overall health care utilization by the two groups did not differ. However, the number of encounters with mental health clinics was significantly different between the two groups. Increased utilization by veterans with PTSD and TBI would potentially suggest a greater need for clinical care due to inadequate medication effectiveness.

Despite a lack of differences in proxy measures of drug therapy outcomes, differences between the groups may still exist. For example, medication changes may have been due to poor response more often among the veterans with TBI than among the veterans without TBI. In fact, many studies have failed to demonstrate improvement with antidepressant use among combat veterans. A high rate of poor response among the veterans with TBI may have obscured potential differences in tolerance between the groups.

We were unable to assess patient outcomes, for example, symptom or functional improvement, in this retrospective study. However, the increased use of certain classes of psychotropic medications may be an indication of poorer response to treatment. It has been suggested that changes in brain structure or function following a traumatic head injury may affect drug response (

7).

The study had several limitations, including the retrospective cohort design. PTSD and TBI require longitudinal assessments, and this study was conducted within a circumscribed interval. We included any patient with an eventual diagnosis of TBI in the TBI and PTSD group regardless of when the diagnosis was made official, given that TBI diagnosis can take several months to confirm. Furthermore, the VHA TBI screening tool we used has not been validated (

14). In addition, some veterans may have refused or not completed screening, and some may have required further evaluation; for these reasons, actual numbers of mild TBI may be higher than found in this study.

We used outpatient pharmacy dispensing information and dates as a proxy for medication adherence, but prescriptions obtained from pharmacies outside the VA are not included, so it is possible that we missed some patients with polypharmacy. Further, because psychotropic medications may have more than one therapeutic indication, a medication may have been used for an indication that was not included as a confounding variable. Last, we were unable to assess the effectiveness of treatment regimens, given that we did not have information regarding symptom or functional improvement.

Conclusions

This study found significant differences in medication therapy for veterans with PTSD when TBI was present. These differences may indicate that patients with PTSD and TBI do not respond to medications in the same manner as patients with PTSD alone.

The results of this study of usual care highlight the need for future research. TBI may be an important variable in drug therapy outcomes, and future studies evaluating PTSD treatments should include patients with PTSD and TBI. Prospective studies are needed to assess the efficacy as well as the safety and tolerability of psychotropic medications in the treatment of PTSD and comorbid TBI.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.