Assertive community treatment (ACT) is an evidence-based model for providing home-based interdisciplinary treatment to adults with severe mental illness living in the community (

1). A key fidelity criterion is that ACT teams provide time-unlimited services, meaning that clients can continue to receive treatment from the ACT team as long as needed (

2). As ACT has spread, some teams, either intentionally or functionally, have interpreted “time unlimited” to mean “forever,” leading to extended stays and little turnover on many ACT teams.

The recommendation that ACT services should be time unlimited evolved from early research that showed a decline in clinical gains 12 months after a planned termination of ACT services (

3). However, when this research was carried out, the alternatives for community treatment in most parts of the United States were quite limited. Since that time, most resource-intensive systems have greatly evolved and include a range of recovery-oriented community-based services, such as clinic treatment, case management, housing, and other supports. Furthermore, the notion that most clients would require ACT as a permanent support is inconsistent with the goal of helping people maximize recovery from serious mental illnesses and move on to a life in the community that includes making one's own decisions about how to best use a range of possible treatment services and supports.

Accumulating research suggests that transitioning from ACT to less intensive services without deleterious effects is possible for many clients (

4–

8). In the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Rosenheck and colleagues (

4) used administrative data to assess outcomes for veterans receiving Mental Health Intensive Case Management (MHICM) services, VA's version of ACT services. They found that only 5.7% of clients who transitioned to less intensive services were readmitted to ACT services, suggesting that most who made this transition did so successfully. Rosenheck and Dennis (

5) examined postdischarge outcomes of ACT clients and found that clients could be selectively transferred from ACT to other services without a consequential decline in activities of daily living and psychiatric stability.

In a retrospective study, records of 98 clients who were transferred from ACT to a step-down model were reviewed and compared with records of a nonequivalent comparison group of 108 clients receiving ACT services (

6). The step-down model was conceived as a reduced-intensity form of ACT that followed many of the ACT principles and core components. Results indicated sustained improvement in functioning and less psychiatric hospitalization for step-down clients than those in the comparison group. McRae and colleagues (

7) followed 72 clients for two years after they transitioned from ACT to mainstream outpatient treatment, noting that most clients remained stable two years after the transition, which the authors attributed to the enduring effects of ACT, the coordinated transition to outpatient treatment, and outpatient providers' dedication in retaining clients in treatment. These findings are consistent with recent research on critical time intervention, which suggests that this time-limited, transitional form of case management can deliver enduring positive impacts by connecting persons with severe mental illness to ongoing support in the community (

9).

Limited research has shed light on individual-level characteristics that are associated with more or less positive outcomes for clients after ACT discharge. For instance, Hackman and Stowell (

8) compared outcomes of 48 individuals who transitioned successfully from ACT to routine services (as evidenced by their continued use of routine services) with outcomes of 19 individuals who returned to ACT or dropped out of treatment. They found that clients who returned to ACT services often had ceased to attend clinic appointments and had been hospitalized, suggesting that an important component of readiness for discharge from an ACT team is the capacity to schedule and keep appointments independently or to have adequate support from other sources (such as a case manager) to help one do so. A recent study of patterns of discharge from MHICM services found mixed results in a retrospective analysis of data from clients who terminated early (defined as less than one year in MHICM services), terminated later (one to three years in MHICM services), or had not yet terminated MHICM services (

10). Compared with clients who had not terminated, clients who terminated early were more likely to be suicidal and display violent behavior. Rates of termination due to uncooperative behavior or service refusal were high for each group (36% of clients who terminated early and 31% of those who terminated later). Thus early termination from ACT, far from being a sign of quick success, may instead reflect failure to engage clients with the most complex needs.

Like many states, New York State has invested heavily in creating ACT teams, many of which now have limited openings for clients because of very long stays in services. As of January 1, 2010, New York State funded 79 ACT teams that were serving 5,064 individuals, with 58% of ACT slots located in the 43 New York City (NYC) ACT teams. This capacity has been fully utilized for several years, with a 95% occupancy rate statewide and 98% in NYC. Most NYC ACT teams began more than five years ago; only seven teams have been licensed since the beginning of 2006. By the fall of 2006, these teams were full and waiting lists had begun. Data from the New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH) indicated that approximately 25% of clients had been on NYC ACT teams for more than five years (

11). This issue had prompted ACT program oversight staff from the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) and OMH to create a utilization review process as part of managing the demand for ACT services. As part of the utilization review process, we created an ACT Transition Readiness Scale (TRS) intended to identify clients who may be ready to transition out of ACT into routine services. The scale was intended as a clinical decision aid to help clinicians and administrators identify clients for whom such a transition process might be appropriate. This feasibility report describes the development of the scale and early efforts to assess its validity. The OMH Institutional Review Board deemed that this project did not constitute research with human subjects.

Methods

Identifying components for the scale

ACT is intended to serve clients who have especially high levels of need for support and treatment and who have not been successfully served by traditional office-based interventions. Thus eligibility criteria typically require multiple recent hospitalizations or homelessness in addition to a serious mental illness (

1,

12). The job of the ACT team is to help the person engage in treatment and achieve greater stability in housing, reduced use of substances, and improved mental health. Hence a scale to assess readiness for transition from ACT to more routine services would logically include measures of whether a client was stably housed, ready to be engaged in treatment with appropriate outpatient treatment providers, avoiding risky or dangerous situations, and not a recent user of crisis services.

A work group composed of staff from OMH and DOHMH (with consultation by ACT team leaders) set out to develop a tool that would verify that individuals currently served by ACT teams are in need of this intensive level of care and identify individuals who may be ready to begin the transition process from ACT to a lower level of support. The intent was to create and pilot test a utilization review tool using client-specific data that ACT teams already were required to report via a standardized assessment reporting system operated by OMH—the Child and Adult Integrated Reporting System (CAIRS). Routine assessments at entry into services and every six months thereafter capture client demographic characteristics and ratings on individual items, which were then collapsed into 11 domains of functioning.

The work group selected seven of these domains (created by collapsing 22 individual items) as relevant to whether a client was ready to transition from ACT to routine outpatient services: housing, psychiatric hospitalization or emergency department use, use of psychiatric medication, engagement in routine services, substance abuse, forensic involvement, and any incidence of harmful behaviors. The four domains of educational and vocational activity, self-care, social relationships, and health and medical status were excluded from estimations of readiness to transition because deficits in these domains alone were deemed not sufficient to justify continuing to receive ACT-level services. Rather, clients doing well in the seven focal domains but still requiring assistance in these other four domains could presumably be successfully transitioned and have these needs met by outpatient mental health service providers or by other community supports.

Scaling within a domain of functioning

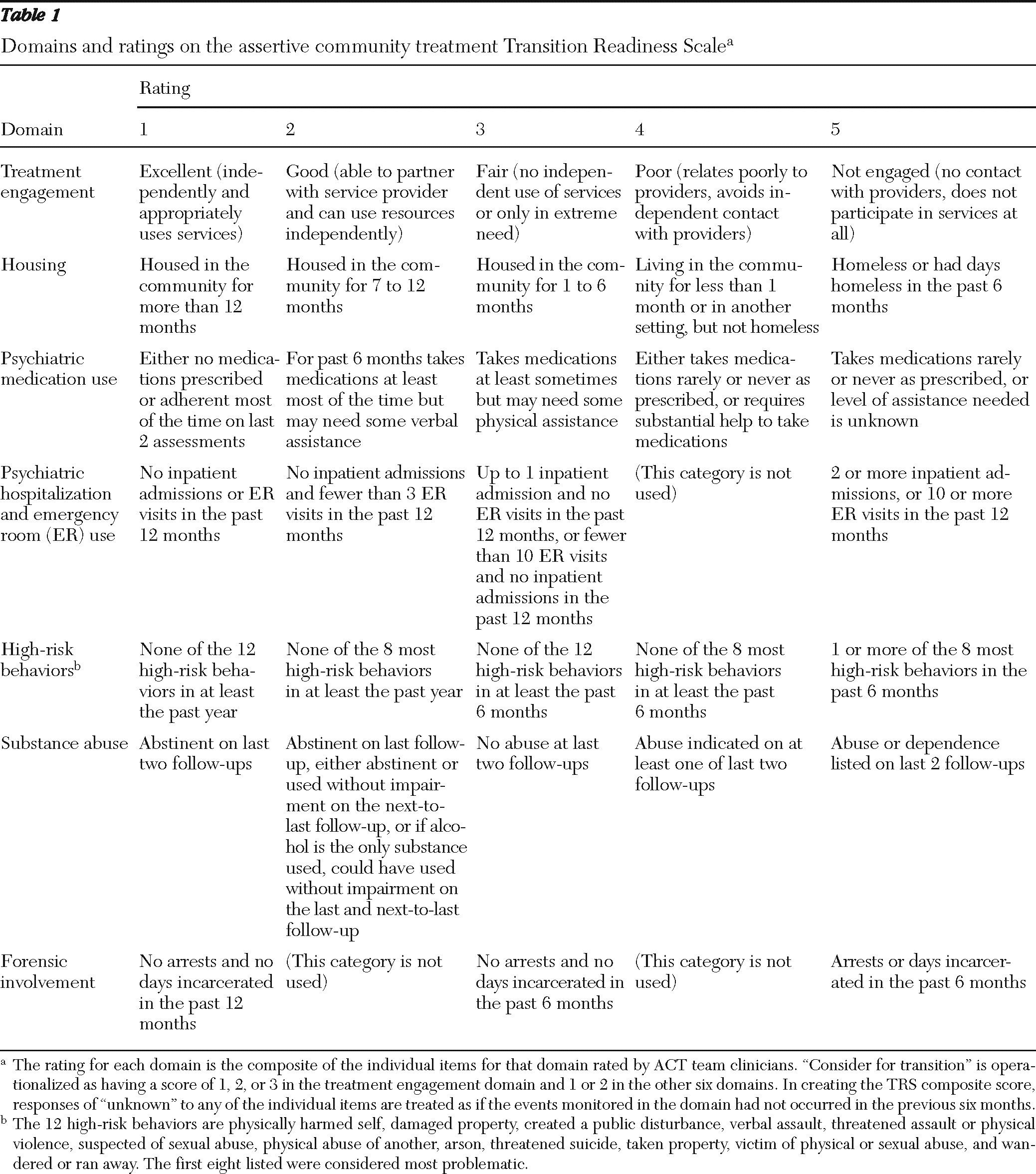

Table 1 shows, for each of the seven domains, the universe of possible composite scores derived from the individual scores on a client's functioning reported by ACT staff. The composite scores range from 1 to 5, plus “unknown.” When creating a composite score on the TRS, responses of “unknown” to any of the individual items were treated as if the events monitored in the domain had not occurred in the previous six months. This approach was chosen to discourage use of “unknown” as a response by staff in order to reduce the number of clients identified for transition readiness assessments.

Creating an overall readiness score

An overall score was calculated by examining scores in the seven domains in

Table 1. The intent was to create an algorithm to assign a client to one of three categories: consider for transition, transition readiness unclear, and not ready for transition. The category of consider for transition was operationalized as having a score of 1, 2, or 3 in the treatment engagement domain and no score greater than 2 in the other six domains relevant to transition readiness. Those in the group labeled transition readiness unclear scored 1, 2, or 3 in the treatment engagement domain, had at least one score of 3 in the other six domains, and had no score higher than 3 in any of the other four domains. The group considered not ready for transition included all others—that is, those who had at least one score of 4 or higher in any of the seven domains relevant to transition readiness.

Pilot testing the TRS

We employed two means of assessing the scale's validity. First, we field tested the instrument with a convenience sample of eight ACT teams chosen by the TRS work group to assess the congruence between the clinical judgment of ACT team staff regarding readiness to transition and the transition scale algorithm. This comparison assessed the extent to which ratings generated by the TRS agreed with a team's clinical judgment. Each participating team was asked to consider all clients on the team's caseload who had been receiving services for at least one year and to assign each of these clients to one of the three readiness categories. Teams made these ratings at a regular morning ACT team meeting so that all team members could provide input into the rating assigned to each client. These ratings were then compared with the rating obtained on the TRS that was based on the CAIRS data previously submitted by the team.

Second, we determined how well ratings produced by the TRS predicted which clients were discharged from ACT because their goals had been met (as reported by program staff via CAIRS). If the scale accurately identifies individuals who are ready for transition, clients coded at discharge as having substantially met program goals (also in CAIRS) should be more likely to have received readiness scores of “consider for transition” than clients who were reported to have been discharged for any other reason.

Data extraction and analysis

In August 2008, OMH staff extracted data for all clients then enrolled in the 42 NYC ACT teams and identified the subset of 1,365 individuals who had at least two follow-up assessments in CAIRS. Because follow-up assessments occur every six months, this meant that each individual in the sample had been enrolled in ACT for at least 12 months. We excluded 251 other individuals who had been mandated to participate in ACT pursuant to a court order because their transition from ACT was influenced by the legal system.

Continuous data were expressed as means and standard deviations and analyzed by use of analysis of variance. Categorical data were expressed as percentages and analyzed by means of a chi square test or Fisher's exact test. We assessed the scale's sensitivity (the proportion of times that clients categorized by the scale as ready for transition were also identified as ready by the clinical judgment of the client's ACT team) and specificity (the proportion of clients identified as not ready for transition by the TRS who also were identified as not ready for transition by the clinical judgment of the client's ACT team). We also used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis methods to evaluate how well the scale performed. Analysis of the ROC provides a precise and valid measure of diagnostic accuracy uninfluenced by prior probabilities, and it places diverse systems on a common scale that is easy to interpret. We examined data for clients deemed ready for transition both by the ACT TRS and by the teams' clinical judgment. We used the teams' clinical judgment as the gold standard in the ROC analysis, using the area under the curve as a summary measure for classification ability. All analyses were performed with the use of SAS, version 9.2. A two-sided p value of less than .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

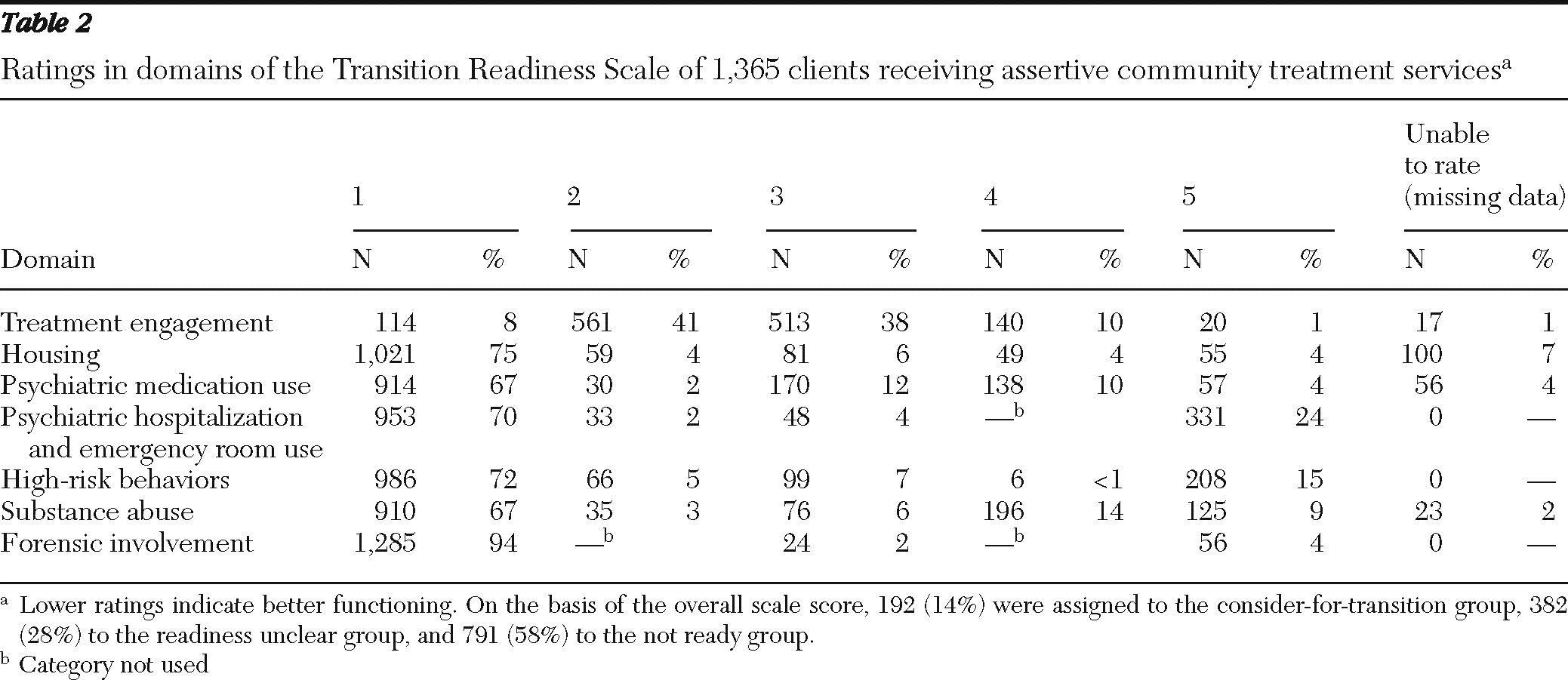

We applied the TRS algorithm to the data in CAIRS for the 1,365 individuals enrolled in NYC ACT teams as of August 2008 who had at least two follow-up assessments. A total of 192 clients (14%) were assigned to the consider-for-transition group, 382 (28%) to the transition readiness unclear group, and 791 (58%) to the not-ready-for-transition group.

Table 2 details the distribution of ratings within each domain and the overall transition scale scores.

Characteristics of clients in the consider-for-transition group

Individuals assigned to the consider-for-transition group had received ACT services for a mean±SD of 4.6±3.0 years (median=3.9 years). For the unclear and not ready groups, means were 4.4±3.1 and 4.0±3.0 years, respectively (medians=3.6 and 3.1 years, respectively). The difference in mean service tenure among the three readiness groups was statistically significant (F=4.38, df=2 and 1,362, p=.013). Individuals assigned to the consider-for-transition group were on average slightly older, with a mean age of 48.3±11.9 years, compared with a mean age of 47.0±13.0 years for the unclear group and 44.8±13.0 years for the not ready group (F=7.43, df=2 and 1,362, p<.01). Although men represented 59% of the cohort overall (N=806), analysis suggested that gender and readiness score groupings were not independent (χ2=6.38, df=2, p=.04). Men accounted for 53% (N=101) of the consider-for-transition group, 57% (N=217) of the unclear group, and 62% (N=488) of the not ready group.

Association with reason for discharge

In addition to the subset of 1,365 clients enrolled as of August 2008, CAIRS contained information for 538 individuals who had at least two follow-up assessments during their ACT tenure and who were discharged from ACT before July 28, 2008, for reasons other than death. Of the 85 persons discharged for positive reasons, 35% (N=30) were classified in the consider-for-transition group and 68% (N=55) were classified in the readiness unclear or not ready groups. Among persons discharged for other reasons, 6% (N=26) were classified in the consider-for-transition group and 94% (N=453) were classified in the readiness unclear or not ready groups.

Concordance with clinical judgment

The eight teams participating in the validation study made global ratings of readiness for transition from ACT for 382 current clients who had been receiving ACT services for at least one year. The teams categorized 58 of the clients (15%) in the consider-for-transition group, compared with the TRS's classification of 68 (18%) as being in this group. Overall, the TRS agreed with the category assigned by the ACT team for 40 clients (69%). The area under the ROC curve obtained for this scale, .80 (SE=.04, p<.001), is considered acceptable discrimination (

13). The specificity was excellent (91.4%) and the sensitivity was acceptable (69.0%).

Discussion

This study showed the feasibility of using routinely collected clinical data to generate transition readiness scores for ACT clients. Among clients enrolled as of August 2008 who had been receiving ACT services for at least one year, the TRS allocated 14% to the consider-for-transition group, 28% to the readiness unclear group, and 58% to the not ready group. In the validation pilot that compared TRS classifications with those made by members of eight ACT teams, the clinicians assigned 15% of their current clients to the consider-for-transition group, and the TRS assigned 18% to this category. Overall, the TRS classifications agreed with the category assigned by the ACT team in 69% of cases. Sensitivity and specificity were both in the acceptable or better range; however, the scale was somewhat better at identifying clients not ready for transition than at identifying clients ready for transition, an attribute we believe is advantageous given the importance of minimizing the likelihood of prematurely transitioning clients who continue to require ACT.

Individuals who had been discharged from ACT for positive reasons were equally likely to be classified into any of the three discharge readiness groups, although most individuals discharged for other reasons were classified into the not ready group. As noted above, these findings suggest that the scale may be better at identifying persons who are not ready for transition. These results also suggest that the TRS may be useful to ACT clinicians and administrators as a way of focusing attention on persons who may be nearing readiness for transition to less intensive services whose progress might otherwise be overlooked because of their continued clear need for services, albeit not from an ACT team.

Given the promising results of this pilot study, we created and distributed reports in August 2009 to all ACT teams in the state listing every client's TRS category rating based on current CAIRS data. Since that time, these reports have been updated and distributed at approximately six-month intervals. The reports are also supplied to state and local administrators who oversee ACT programs regionally. ACT teams use the scale to facilitate identification of clients ready for transition and to commence implementing transition plans. Discussion of progress toward transition has been instituted throughout the state as an ongoing component at regularly scheduled meetings of ACT teams and administrative staff. In NYC and Long Island, the process has been formalized further by requiring ACT providers to submit either a written justification for continuance on the ACT team or a plan for transition for each client categorized by the TRS as “consider for transition.”

Anecdotal feedback from ACT teams indicates that the TRS is a useful tool and that having the team's clinical ratings summarized in this manner is a helpful way of turning data into actionable information by identifying clients who, although not necessarily ready for immediate discharge, are those about whom transition discussions are germane. Furthermore, although the information contained in the TRS reports is presumably already available to ACT team members (because they provide the data on which the reports are based), such reports provide additional value by summarizing data collected over several assessment points to supply clinicians, supervisors, and administrators with concise and clinically relevant information that can be reviewed quickly and efficiently.

There are several limitations to the study. First, the source of data for the scores was limited to ratings made by ACT team staff and did not incorporate data provided directly by clients. Recent efforts to incorporate shared decision-making approaches into mental health services suggest that clients' judgments about their own capacities, needs, and preferences provide critically important information that can be used to tailor psychiatric treatment and other services (

14,

15). Second, the sample of eight ACT teams was drawn for convenience rather than systematically; however, the programs selected and their caseload mix are similar to many urban ACT teams in New York State. Third, we lacked data on the interrater reliability or agreement between ACT team clinicians for individual data elements of the TRS and on the test-retest reliability of the scale. Work is needed to carry out a formal reliability analysis of the scale. Finally, it is important to clarify that the TRS is not intended as an objective or gold standard indicator of readiness for transition from ACT. Rather, the TRS summarizes diverse ratings of client functioning provided by clinicians to help identify clients for whom transition may be appropriate.

Potentially productive work in this area would include further psychometric testing of the TRS (ideally incorporating clients' self-rating data) that can improve the sensitivity of the measure without significantly reducing its specificity. Such work should be followed by a larger, systematic trial in which its efficacy in a representative sample of ACT teams can be rigorously evaluated. Ideally such a trial would assess the degree to which the TRS enhances the capacity of ACT clinicians to identify clients who are approaching readiness for transition and to examine postdischarge outcomes of discharged clients.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations noted above, we believe that this pilot work represents a promising step toward the further development and testing of an ACT TRS that could be efficiently employed in routine practice in New York State and other public mental health systems. Although the data we used to generate TRS scores were gathered routinely via the state's centralized clinical reporting system, it is possible that service systems without access to such reporting tools could implement a similar approach at the individual program level. The number of items used to generate scores is modest, scoring is simple, and relatively little training is needed to enable ACT clinicians to produce the ratings. Thus an approach similar to the one we have described could be broadly implemented at relatively low cost in systems that offer ACT services. Furthermore, as public mental health systems move toward widespread adoption of electronic medical records, the feasibility of such an approach is likely to improve (

16).

Client slots on ACT teams represent scarce and expensive treatment resources, necessitating careful attention by both clinicians and administrators to identify clients who may be ready to transition to less intensive clinical services, thereby opening places for other clients who can benefit from the intensive support that ACT provides. Because ACT cases are complex, providing simple but valid and reliable data summaries in a timely way can be a useful tool that program staff and supervisors can use to augment their existing approaches to ongoing service delivery and transition planning for their clients. The TRS is an example of one way in which such data can be delivered.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This validation study received financial support from the New York State Office of Mental Health. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Gary Clark, M.S.W., Robert E. Drake, M.D., Ph.D., Molly Finnerty, M.D., and Candice Stellato, M.S.W., to the conceptual development of the Transition Readiness Scale.

The authors report no competing interests.