An expected increase in the number of adults over the age of 65 with psychotic disorders and other serious mental illnesses portends “an emerging crisis” (

1) for general medical and mental health service systems (

2,

3). Because of a range of lifestyle factors, problems in negotiating fragmented care systems, substandard housing, poverty, and iatrogenic effects of antipsychotic medications, persons with psychotic disorders in middle age are at greater risk for chronic health problems than their peers without mental disorders (

4–

6). As these adults age, their health and functioning are further compromised by the physical, social, and cognitive decline associated with natural aging.

Unfortunately, despite their increased need for appropriate and continuous health care, older adults with psychotic disorders face significant difficulty in accessing high-quality general medical and mental health services across the continuum of care (

7). In addition, the reciprocal relationship between poor general health and mental health functioning may delay help seeking, complicate coordination of care, and disrupt relationships with formal and informal caregivers, adherence to treatment regimens, self-care, and engagement in health promotion activities (

8,

9). As a result, older adults with psychotic disorders are in “double jeopardy” for a range of poor outcomes, including premature mortality, prolonged physical frailty, and an inability to age in place (

7,

10,

11). Furthermore, the complex health problems of older adults with psychotic disorders result in significant costs to public financing systems (

12,

13).

Considering the personal and public costs associated with serious mental illness among older adults, it is important to examine the outcomes of these persons as they transition through the care system (

2). In particular, this study examined the outcomes of older persons with psychotic disorders after a general hospital stay. A limited number of studies have examined the outcomes of this population after acute care. These studies suggest that compared with their peers without mental disorders, persons with psychotic disorders are more likely to have longer general hospital stays (

14), greater mortality after an acute care event, and less access to best practices during hospitalizations (

15). For example, after acute care for myocardial infarction, older persons with schizophrenia were 34% more likely than those without a mental disorder to die within one year (

15). However, these existing studies have not sufficiently examined acute care outcomes other than posthospitalization mortality, such as discharge to home care services or to a nursing facility or death in the hospital, and their samples were limited to older adults with psychotic disorders and a concurrent diagnosis of dementia or to individuals treated by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

To expand on the findings of prior research documenting the acute care outcomes of older adults with psychotic disorders, this study examined the extent to which psychotic disorders predicted the likelihood of receiving a discharge disposition of routine discharge, home care, or nursing facility care or of in-hospital mortality among older adults after a hospital stay for a general medical condition. Data about disposition and demographic and clinical characteristics were drawn from a nationally representative sample from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The study tested the hypothesis that after adjustment for demographic and clinical characteristics, older adults with psychotic disorders would be more likely than their peers without a psychotic disorder to require home-care services and nursing home care and to die in the hospital.

Methods

Data were drawn from the 2007 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) of the HCUP (

16). HCUP data are collected and managed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The NIS is the largest all-payer publicly available database of inpatient hospital discharges in the United States and contains data on five to eight million hospital stays drawn from a stratified sample of 20% of community hospitals (

17). The NIS contains over 100 clinical and nonclinical patient-level variables.

The sample of discharged inpatients used for this analysis excluded those aged 64 or younger, those with a primary or secondary diagnosis of dementia (ICD-9 codes 290–294), and those with a primary mental health diagnosis (ICD-9 codes 295–319). The latter exclusion was used to identify patients who had been hospitalized for medical conditions rather than those needing primarily psychiatric treatment. Discharged patients with dementia were excluded to assess the effects of a psychotic disorder that did not occur jointly with severe cognitive impairment. Discharges were classified as having a psychotic disorder if they had a secondary ICD-9 diagnosis between codes 295 and 297.

Patient-level variables selected for this analysis included demographic characteristics (age, gender, and race) as well as clinical characteristics, including

ICD-9 codes for primary and secondary diagnoses, discharge disposition, severity of medical illness, admission from another inpatient facility, and comorbid illnesses (alcohol or drug use disorder, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity). The HCUP considers comorbidities to be those conditions that are not the primary reason for the hospital stay but that probably existed before the admission and have the potential to complicate care (

18). Severity of illness was measured by using the All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups software, which defines illness severity with a clinical algorithm that simultaneously evaluates multiple comorbid illnesses, age, use of medical procedures, and primary diagnoses (

19).

The dependent variable, discharge disposition, was constructed as a categorical variable with four levels—routine discharge, discharge to home care, discharge to nursing facility, or death occurring during the hospital stay. Discharge to routine care included patients discharged to home with self-care. Home care discharges included patients who were transferred to home with a formal referral for skilled home health care. Discharges to a nursing facility included patients transferred to a bed in a facility for skilled or custodial care other than inpatient hospice care.

Chi square analyses were performed to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of discharged inpatients with and without psychotic disorder. A multinomial logistic regression model assessed the impact of psychotic disorder on discharge disposition, controlling for demographic and clinical characteristics. The model was repeated for each stratum of the demographic and clinical characteristics. Finally, to assess if the impact of psychotic disorder varied across strata of the control variables, a series of logistic models that included an interaction term between psychotic disorder and each independent variable was constructed. All the logistic models used routine discharge as the reference group. Analyses were performed by using SAS 9.2 statistical software. All analyses used sampling weights to account for the NIS sampling design.

The analysis was exempt from review by the institutional review board because the data set had been deidentified and was in public use.

Results

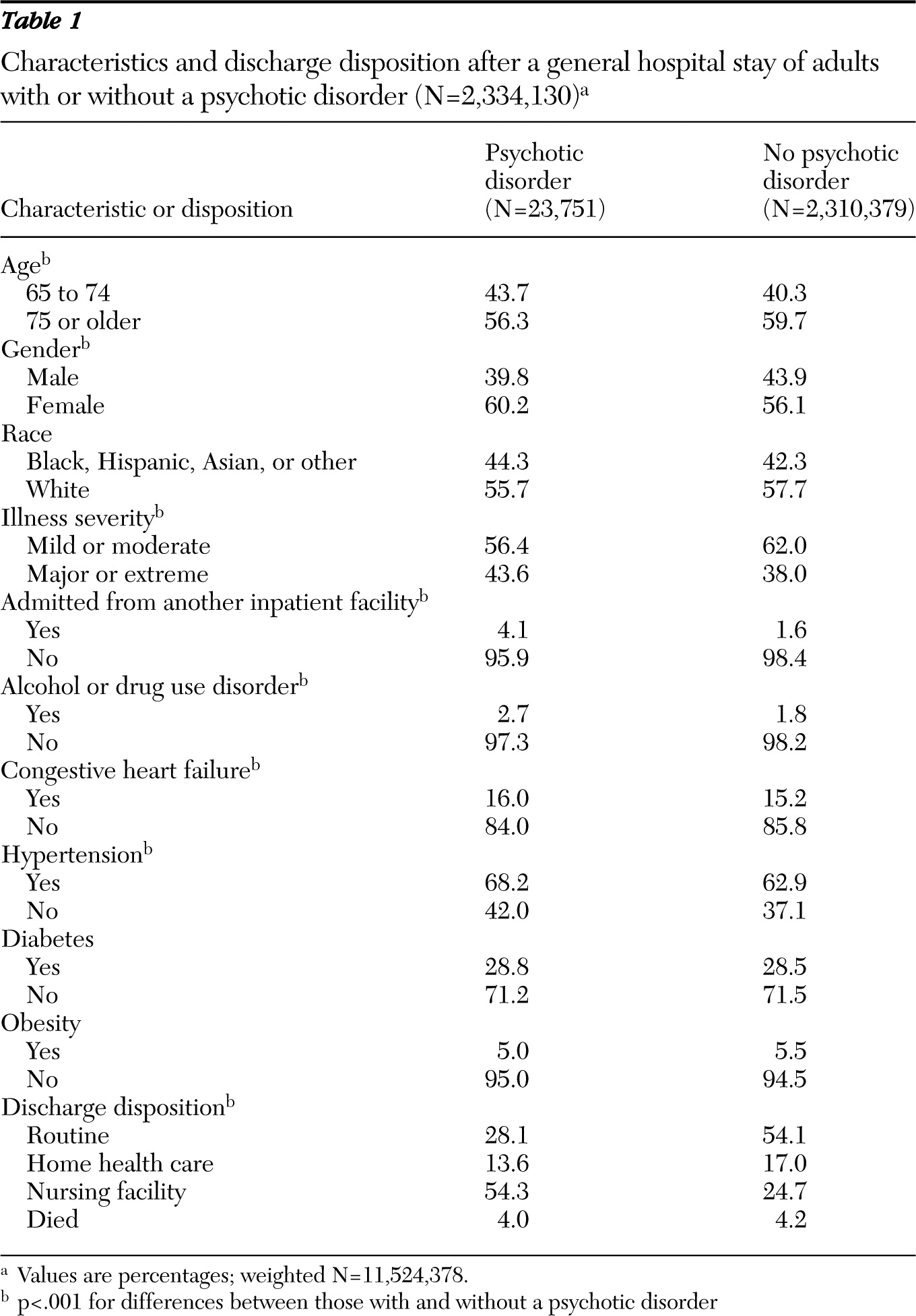

Characteristics and disposition of discharged inpatients with psychotic disorder (N=23,751) and without such a disorder (N=2,310,379) are summarized in

Table 1. Approximately 1% of the total sample had a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, 60% were over the age of 75, 56% were female, 58% were white, and 38% had illness of major or extreme severity. Nearly 54% of patients were discharged to routine care, 17% to home care, and 25% to a nursing facility; 4% died in the hospital.

Unadjusted chi square analyses demonstrated that the discharge dispositions of inpatients with a psychotic disorder differed from those without a psychotic disorder. Approximately 28% of discharged patients with a psychotic disorder had a routine discharge compared with 54% of those without a psychotic disorder. Nearly 54% of those with a psychotic disorder were discharged to a nursing facility compared with 25% of those without a psychotic disorder. Chi square analyses also indicated that patients with a psychotic disorder differed significantly from those without a psychotic disorder by age, gender, illness severity, admission from an inpatient facility, and existence of a comorbid alcohol or drug use disorder, congestive heart failure, and hypertension.

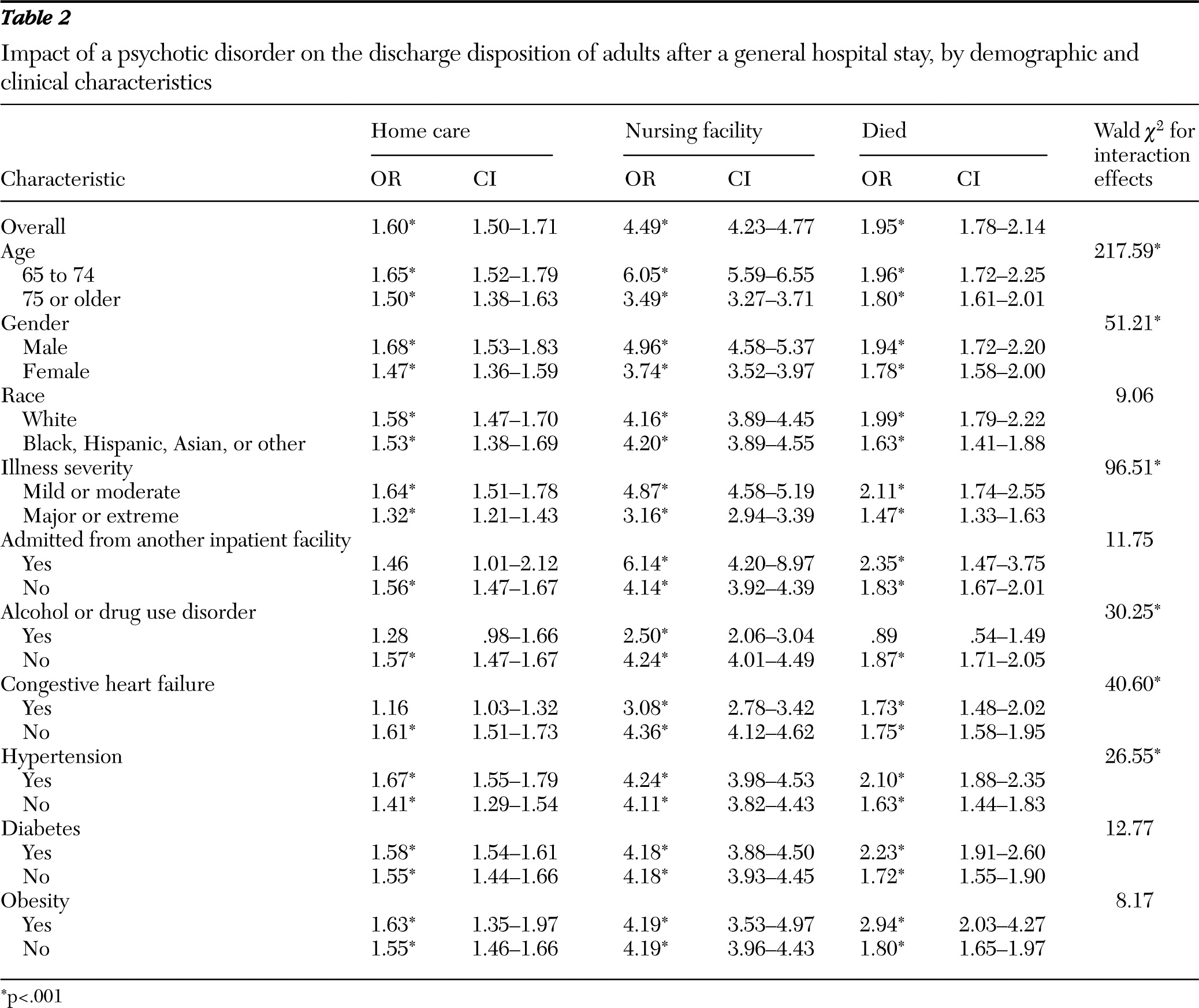

Table 2 displays the results of multinomial logistic models that examined the impact of a psychotic disorder overall and within each patient-level subgroup on the likelihood of discharge disposition. In the overall model, discharged patients without a psychotic disorder were significantly more likely than those with a psychotic disorder to be discharged to home care (odds ratio [OR]=1.60, p<.001), to be discharged to a nursing facility for skilled or custodial care (OR=4.49, p<.001), or to die in the hospital (OR=1.95, p<.001).

With few exceptions, among patient-level subgroups, patients with a psychotic disorder were more likely than those without a psychotic disorder to be discharged to home care or a nursing facility or to die in the hospital. In particular, among younger inpatients and those admitted from a nursing facility, patients with a psychotic disorder were approximately six times more likely than those without a psychotic disorder to be discharged to a nursing facility. In addition, among males and those with illness of mild or moderate severity, patients with a psychotic disorder were approximately five times more likely than those without a psychotic disorder to be discharged to a nursing home.

Table 2 also displays the Wald chi square statistics for each of the interaction terms tested in a series of logistic regression models. The interaction of age and psychotic disorder (Wald

χ2=217.59, p<.001) produced the most significant effect on discharge disposition, followed by illness severity, gender, congestive heart failure, alcohol or drug use disorder, and hypertension.

Discussion

Older adults with a psychotic disorder are a growing population with complex care needs across the continuum of general medical and mental health services. This study, in an effort to further understand the care trajectories of these adults within the health system, used a nationally representative sample to examine the outcomes of older persons discharged from a general hospital stay. It adds to the findings of prior studies by comparing discharge dispositions (routine, home care, nursing facility, or in-hospital mortality) among inpatients with and without a psychotic disorder from acute care while controlling for a range of demographic and clinical characteristics.

As expected, compared with those without a psychotic disorder, patients with a psychotic disorder were more likely to be discharged to skilled home care, transferred to a nursing facility for skilled or custodial care, or to die in the hospital. These results were fairly consistent across demographic and clinical subgroups. However, an increased likelihood of discharge to a nursing facility for those with a psychotic disorder was particularly pronounced among younger inpatients, males, those admitted from an inpatient facility, and those with less severe medical illnesses.

These findings support a large body of research documenting higher mortality rates among persons with a serious mental illness (

20,

21). The results suggest that even among subgroups of patients who are younger and have less severe medical illnesses, older persons with a psychotic disorder are at significant risk for discharge to skilled or custodial support. This finding is consistent with prior studies that suggested that even when controlling for factors that commonly lead to nursing-home admission—including severity of illness, age, and cognitive impairment (

22)—having a psychotic disorder leads to increased risk of admission to a nursing home. For example, in a large representative sample of VA patients, those with schizophrenia without comorbid dementia were nearly twice as likely to be admitted to a nursing home (

10).

It is unclear from the results of this study if the discharge dispositions of persons with a psychotic disorder after an acute care episode were clinically appropriate or optimal care options. Discharge to nursing facilities, especially among the younger inpatients with a psychotic disorder, however, is likely related to a dearth of home- or community-based care settings, residential care options, and informal caregivers. When such conditions exist, nursing facilities may emerge as the only, albeit costly, care option for safe discharge (

23).

In addition, complications during the hospital stay for persons with a psychotic disorder may prohibit a more expedient return to baseline functioning. Problems in executive functioning and other cognitive impairments, treatment refusal, problems in communicating with providers, differential diagnosis, and behavioral problems may compound the risk for discharge to home- and facility-based care. Furthermore, the presence of such complicating factors may partially explain why inpatients with a psychotic disorder admitted from another inpatient facility were particularly at risk for discharge to a higher level of care, even after the analysis controlled for other patient characteristics.

Institutionalization for short or long stays has significant consequences for quality of life and is often counter to the desires, preferences, and best interest of older adults with serious mental illnesses. Many of these persons, like their peers, prefer to age in place and be served in community settings. Indeed, a recent analysis highlighted that providers in nursing home settings deemed community-based settings as the more appropriate setting for their residents with mental health problems (

24).

In addition, integrated health and mental health services are an effective mechanism for promoting health and well-being for frail older adults with a psychotic disorder (

25). Although older adults in this study frequently were referred for continued medical support in the community, their ability to obtain needed specialty mental health care in home and facility settings was questionable. Commonly, as a result of a lack of trained providers in the workforce and insufficient reimbursement rates for skilled and custodial care, nursing homes are not equipped to provide the specialty mental health services necessary to stabilize psychotic symptoms and related behavioral problems (

26). Similarly, home care services are often limited to medical intervention and do not address the psychiatric needs of frail older adults after a medical event.

Finally, post-acute care interventions, including home care and nursing facility care, are extremely costly to public financing systems. Medicare and Medicaid expenditures for persons with schizophrenia exceed those for other frail older adults, such as those with dementia (

12). In light of current budget deficits and cost cutting in social safety net programs, delineating strategies for reducing the cost of care to this population, while increasing access to appropriate community-level general medical and mental health services, is imperative.

This study had several limitations. The analysis used cross-sectional data derived from medical records and, therefore, was unable to confirm the accuracy of patient diagnoses or to follow outcomes over time. It is unclear from the study if patients discharged to a home-care provider were able to obtain those services or if patients were adherent to treatment recommendations in the community. Likewise, the data set did not include details of the dispositions examined such as the number of home-care visits recommended or if the nursing facility discharge was for skilled or custodial care.

Conclusions

This analysis demonstrated that older adults with a psychotic disorder are at significantly greater risk for needing skilled or custodial care after a general hospital stay than their peers without this disorder. In particular, those with a psychotic disorder were nearly five times more likely to be discharged to a nursing facility. Considering the complexity of comorbid general medical health and mental health disorders and the lack of appropriate community care options and informal caregivers, nursing facility care may be the only viable care setting for many of these frail adults. However, nursing home care is costly and may not be the preferred or most clinically appropriate option for this population. Furthermore, access to specialty mental health care in both home care settings and in nursing facilities is limited.

These results highlight the need for providers and policy makers to devise strategies for providing integrated general medical health and mental health services for this population within less restrictive, community-based care settings. Furthermore, future prospective studies should examine the care trajectories of older persons with psychotic disorders over time and more closely examine the patient-, provider-, and system-level process dynamics that contribute to these particular outcomes.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Marcus has received grant support from Ortho-McNeil Janssen and has served as a consultant to AstraZeneca. Dr. Bressi Nath reports no competing interests.