Bipolar disorder is a chronic affective disorder that results in substantial impairments. According to the World Health Organization, bipolar disorder is ranked sixth among all medical disorders in years of lost life due to death or disability (

1), and it has been consistently rated among the top causes of disability-adjusted life years for 15- to 44-year-olds in developed countries (

2). Individuals with bipolar disorder generally experience a chronic, recurrent course of illness that increases their risk of lifelong disability and greatly affects their lives and the lives of their families (

3).

Once considered rare among children, bipolar disorder diagnoses have increased sharply in this population in both inpatient and outpatient settings, according to recent studies (

4–

8). Children with bipolar disorder have significantly higher rates of morbidity and mortality than children without the disorder (

9), including psychosocial morbidity, impaired academic performance, impaired social and familial support, increased levels of substance abuse, weight problems, legal difficulties, and hospitalizations (

10–

14). Although the criteria for diagnosing and the use of the bipolar diagnostic label among children with nonclassical symptom presentations are matters of clinical debate (

14,

15), a growing number of children over recent years have received these diagnoses and related treatment.

In addition to the enormous personal and familial burden, the economic impact of bipolar disorder is extremely high, particularly after accounting for the opportunity costs of living with a mental illness (

16). In fact, a 2003 study found that bipolar disorder was the most expensive behavioral health diagnosis for both patients and their insurance plans (

17). With the knowledge that over 90% of patients with bipolar disorder suffer recurrences and many experience progressive deterioration in functioning (

18), it is important to consider the financial impact of this disease from both the family and the health plan’s perspective.

The costs related to treating children with bipolar spectrum disorders are likely to differ from those for treating adults. No cost-related study of bipolar disorder (

19–

25) has focused on children. In addition, only two studies have used data from 2003 or later (

19,

25). This dearth is a critical limitation for several reasons. First, during the past decade, there has been a dramatic increase in the diagnostic prevalence of bipolar disorder among children. Second, the number of psychotherapeutic treatment options (including second-generation antipsychotics and anticonvulsants) has grown. Finally, inpatient lengths of stay among patients with mental illness, including children, have also decreased (

7), suggesting that costs for bipolar treatment may have shifted from inpatient to outpatient care.

Research has found that families with private health insurance are more likely to be underinsured and to report inadequate coverage of needed services, especially families of children with special health care needs (

26). Given that private health insurance remains the dominant payer for children’s mental health and hospital services (

27), estimating service use and costs of treatment for privately insured youths with bipolar disorder will help to quantify the impact of this disorder on children, their families, and the health care system. The objectives of this study were to identify utilization patterns and estimate health plan payments for inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy services among privately insured children with bipolar disorder diagnoses.

Discussion

Although there has been increasing attention paid to pediatric bipolar disorder over the past decade, little is known about treatment utilization patterns and costs in this growing population. In this sample the mean one-year total health care costs among children were found to be remarkably similar to published cost estimates for adults with bipolar disorder (

19–

25,

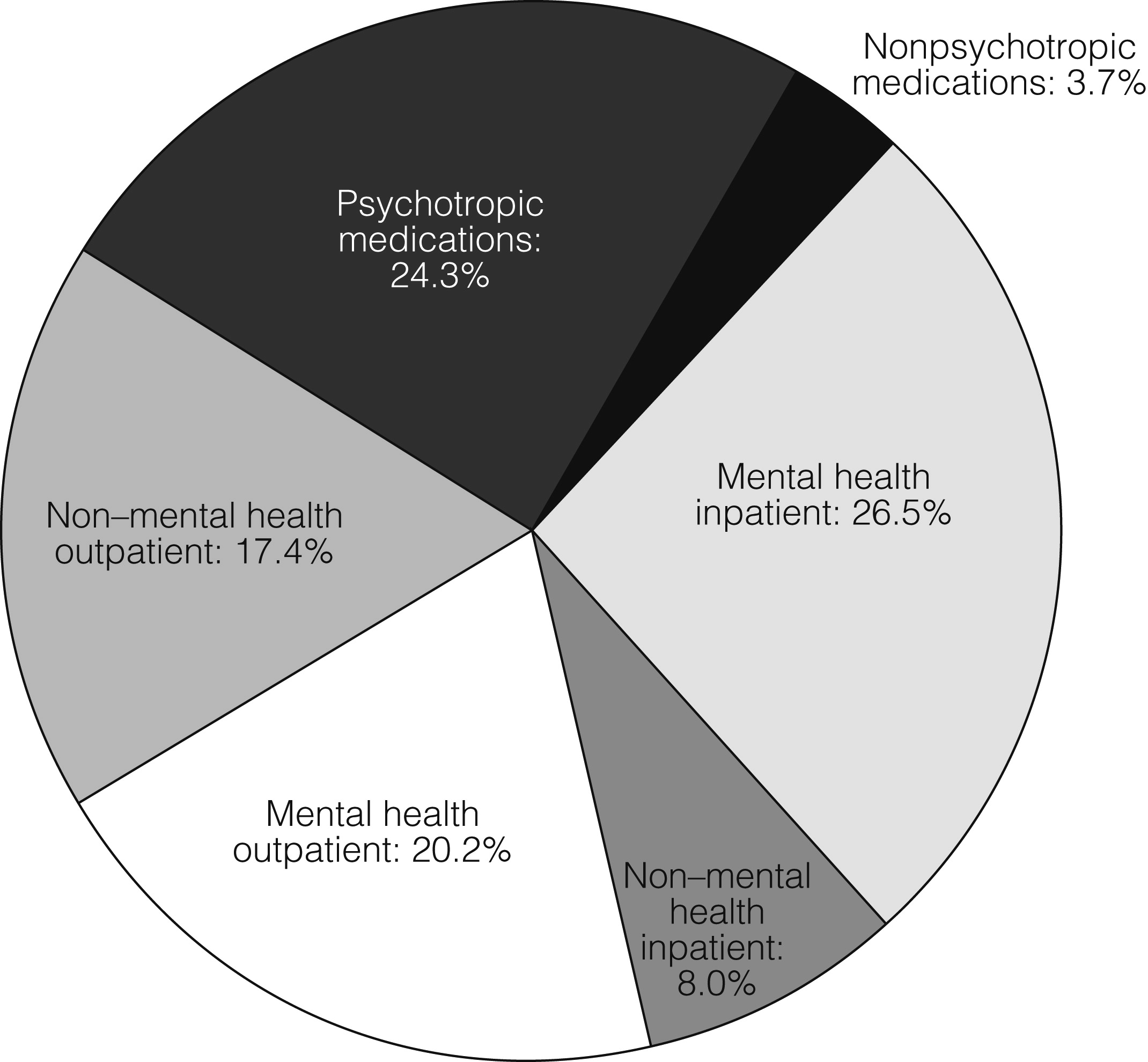

33). Outpatient costs made up 38% of total costs, inpatient costs made up 35%, and medication costs 28%, which are similar to estimates for adults (

20). However, mental health–related spending represented 71% of total spending in this sample. This finding is in contrast to estimates in adult samples (

21) that have found spending on mental health care to represent only 22% of health care spending.

When considering the differences between adults and children in the proportion spent on mental health care compared with total health care, it is important to note that cost estimates also include care for chronic medical conditions, which are more prevalent among adults than among children. As such, a higher concentration of spending on mental health services was anticipated for children compared with adults. However, lower total costs of care (mental health and non–mental health care combined) were also anticipated for children, given the expectation of higher non–mental health spending among adults. Instead, total costs were similar when comparing estimates for adults and children because of higher spending on mental health treatment among children. This may be due to difficulties in accurately diagnosing bipolar disorder among children (that is, diagnostic uncertainty) and the high rates of comorbid mental health conditions that accompany pediatric bipolar disorder.

For non–mental health care, outpatient care was the highest cost category. This was due primarily to high levels of utilization of services, rather than high costs of services in this category. Closer evaluation of the study sample showed that nearly 56% of non–mental health outpatient visits had total costs of less than $100, and nearly 91% had total costs of less than $500. The most common diagnosis coded for non–mental health visits was for routine infant or child health check-ups. Other common reasons for visits were acute sinusitis, acute pharyngitis, respiratory infections, allergies, asthma, abdominal pain, and fatigue or malaise.

Understanding the financial burden of pediatric bipolar disorder treatment is important because previous studies found that even among families with private insurance coverage, families with children with special health care needs (including mental health) have significantly greater financial barriers than families with children without these conditions (

34,

35). Research suggests that up to 25% of continuously insured families with private health insurance are underinsured, as defined by the family’s perspective on the reasonableness of out-of-pocket expenses (

26). In the study sample, families paid on average $1,429 out of pocket during one year of a child’s bipolar disorder. These payments represent the reported patient out-of-pocket expenses (copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles) but do not include premiums paid by the patient. In addition, these estimates do not consider indirect costs, such as lost productivity or absenteeism from work or school (for family members or the patient), child care, or other time and services for managing the child’s bipolar disorder. Given the chronic, recurrent nature of bipolar disorder, these costs may be substantial.

Private insurance plans have historically limited mental health service benefits more aggressively than general medical benefits. In this sample there was some evidence of higher cost sharing for mental health care than for general medical care. For example, when looking at the total costs of outpatient mental health services, we found that 54% of total costs for outpatient services were mental health related, yet these visits accounted for 60% of the patient’s out-of-pocket costs. Similarly, 77% of inpatient costs were mental health related, but these accounted for 92% of patient out-of-pocket inpatient costs. Not surprisingly, this relationship was not found with psychotropic medication cost sharing because medications are generally managed separately from mental health benefits.

Recently there have been important changes in the legislation for determining mental health benefits. With the signing of the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act in October of 2008 (P.L. 110-343), and more recently the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, employer-sponsored health plans are now required to cover mental health and substance abuse services at the same level as medical-surgical benefits. These policy changes may help to reduce the discrepancies between the mental health and non–mental health cost-sharing burden as described earlier. However, insurers are able to opt out of offering mental health and substance abuse treatment, or they may elect to cover only specific disorders (

36). Given the high proportion of spending on mental health services among privately insured children with bipolar disorders, monitoring health plan coverage for bipolar disorder and the impact of benefit changes on children’s health services utilization is important.

Although no previous studies have estimated total costs of treating bipolar disorder, our inpatient cost and utilization estimates are consistent with a recent study focused on estimating the inpatient burden of pediatric bipolar disorder. In that study, average costs of inpatient treatment were slightly higher but similar to our results, and differences between estimates were likely due to higher costs and longer inpatient stays among youths on Medicaid in the former study (

37).

Data directly comparing health care costs for our bipolar sample and similarly aged children, or even subgroups of patients with other chronic conditions, are not readily available. One example of comparison data for a similar population comes from a study of children with diabetes. That study assessed the total average annual costs of diabetes treatment in 2007 with the MarketScan insurance claims data and found that youths with diabetes had $9,061 average annual total expenditures, whereas youths without diabetes had expenditures of only $1,468 (

38). In contrast to these estimates, average annual total costs for youths with bipolar disorder in this study were $10,372 (in 2007 dollars), with much of this cost attributed to mental health–related spending. Costs for non–mental health treatments among children with bipolar disorder in our sample were also higher than costs estimated for children without diabetes. Reasons for this may include more frequent health care utilization or possibly increased physical comorbidities associated with treating bipolar disorder (such as metabolic conditions that developed subsequent to usage of second-generation antipsychotics).

There are several limitations that are important to consider when interpreting the results of this study. First, administrative claims rely on diagnosis codes, rather than on structured evaluations, to identify patients with bipolar disorder, which may have resulted in disease misclassification. In an attempt to minimize bias from misclassification, we restricted the sample by including only children with more than one bipolar diagnosis or an inpatient stay, which has been shown to increase the specificity of the diagnosis (

39). Related to this caveat, a large proportion (50%) of our sample received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (bipolar NOS). This diagnosis may represent diagnostic uncertainty on the part of the clinician. It is unclear whether children with these diagnoses would convert to a bipolar type I or bipolar type II diagnosis, but evidence suggests that conversion from bipolar NOS to a more specific diagnosis occurs frequently among youths (

40). It is important to bear in mind that inclusion of children with less severe behavioral diagnoses would likely result in conservative estimates of treatment costs and utilization for the sample.

Second,it is unclear whether diagnoses made in childhood persist as the child ages into adulthood, although some suggest that bipolar I and bipolar II designations may be continuous from childhood to adulthood (

41). These factors may affect the long-term costs of treatment but would not affect the short-term estimates provided in this study. Third, total costs are based on actual payments received by physicians from both the health plan and the patient. These costs are based on negotiated prices between the health plan and the provider and may not be generalizable to publicly insured or to uninsured populations. Finally, cost estimates generated for patient out-of-pocket payments must be interpreted with caution because details on the cost-sharing arrangements between health plans and patients (such as the plan premium) were not available for this analysis.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding for this project was provided by a National Research Service Award grant 5-T-32 HS000032-20 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). AHRQ played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Dusetzina is funded by a Ruth L. Kirschstein-National Service Research Award T32MH019733-17 sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and Harvard Medical School, Department of Health Care Policy. Dr. Weinberger receives support from a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Scientist Award (RCS 91-408). Dr. Gaynes has received support from a grant from the NIMH and AHRQ.

Dr. Farley has received consulting support from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Gaynes has received grants and research support from Ovation Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and M-3 Corporation and has been on advisory boards of Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Shire Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sleath is a consultant for Abbott Laboratories on risk communication and a consultant for Alcon Research Ltd. on glaucoma research. Dr. Hansen has received research and consulting support from Takeda, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, and Novartis. Drs. Dusetzina and Weinberger have no competing interests.