Helping individuals maintain functioning after discharge from inpatient care presents a continuing challenge (

1–

4). The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides its most intensive treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in residential rehabilitation programs (

5). The structure of these programs varies, but most combine pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy to teach coping skills, and opportunities to practice these skills in a therapeutic milieu. Some programs offer evidence-based psychotherapies for patients who are deemed appropriate candidates. Average length of stay varies by program from 15 to 90 days (

5). Veterans treated in residential PTSD programs often have co-occurring problems, including depression, anger, and interpersonal difficulties (

6,

7). Many have histories of substance misuse, although veterans must be abstinent from substances when they enter residential PTSD treatment (

8,

9).

Several studies have questioned the effectiveness of inpatient treatment programs for PTSD and whether gains are adequately maintained after discharge (

10,

11). Many veterans continue to have difficulties after completing residential treatment. In one program, 12% of patients relapsed to heavy drinking, 9% relapsed to illicit drug use, and 48% reported aggressive behavior within four months of discharge (

9). Other studies reported that after discharge from residential PTSD treatment programs, 10% of veterans were rehospitalized within four months and 21% were rehospitalized within a year (

1,

12).

Improving outpatient treatment attendance and medication compliance among veterans after their discharge from intensive PTSD treatment could potentially enhance their functioning. Dropout from outpatient mental health treatment is a common problem in the general population (

13,

14) and among veterans (

15,

16). Over one-quarter of veterans did not complete an outpatient treatment visit in the first 30 days after discharge from VA residential PTSD treatment programs (

1,

17). Poor compliance with medications might also contribute to poor outcomes (

18,

19). In one study, only one-third of veterans who were prescribed antidepressants during residential PTSD treatment consistently refilled them after discharge (

12).

Prior studies have shown that telephone monitoring and support can facilitate initial entry into mental health treatment (

20,

21), enhance medication compliance (

19,

22), and reduce rehospitalization (

23). Telephone-based care management can improve outcomes for depression and alcohol use disorders among patients treated in primary care (

24–

26). Telephone-based continuing care has reduced relapse among patients discharged from intensive treatment of addiction (

27,

28). A quasi-experimental pilot study confirmed that providing biweekly telephone support to veterans after discharge from residential PTSD treatment was feasible, was acceptable to patients, and reduced time from discharge to completion of a first outpatient visit (

17).

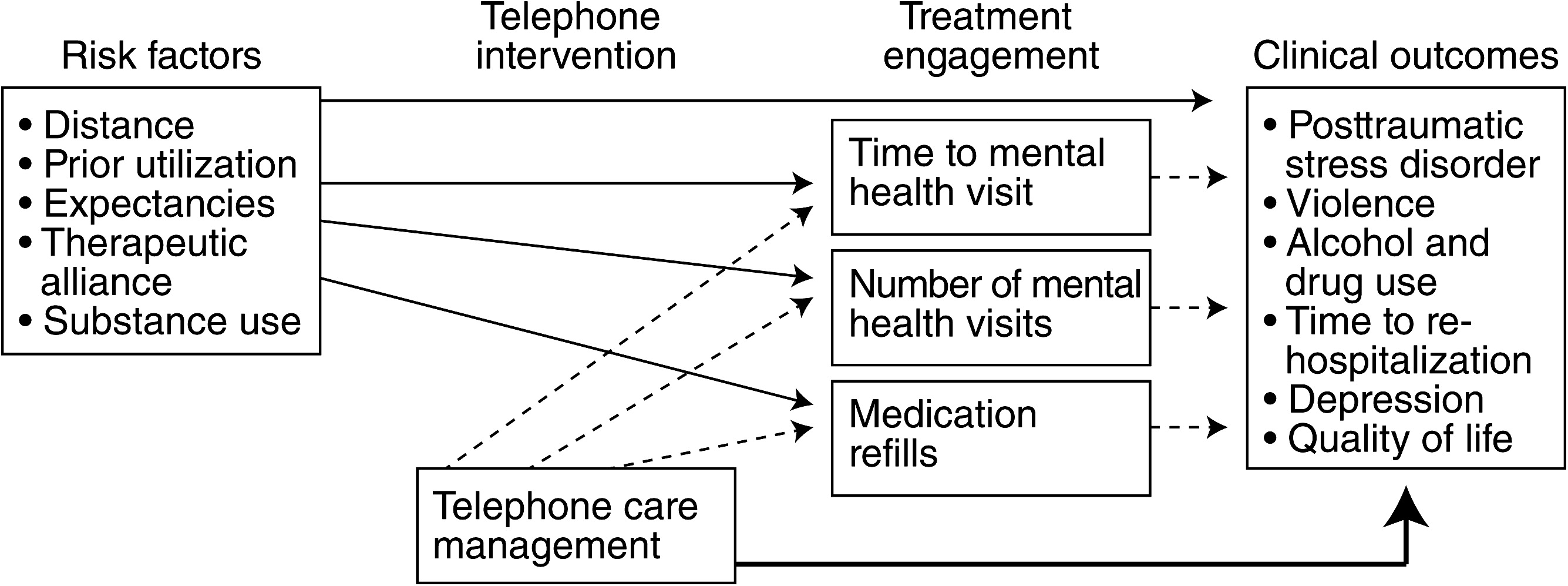

This study tested whether augmenting usual aftercare with biweekly telephone monitoring and support would improve veterans’ outcomes after discharge from residential PTSD treatment. The model underlying our study hypotheses is depicted in

Figure 1.

Our primary hypotheses were that veterans randomly assigned to the telephone care condition would have less severe PTSD symptoms, fewer aggressive behaviors, and less severe alcohol and drug use problems four and 12 months after discharge compared with veterans who received treatment as usual. Our secondary hypotheses were that participants who received telephone care would have longer time to rehospitalization, less depression, and better quality of life four and 12 months after discharge compared with veterans who received treatment as usual.

The tertiary goal of the study was to assess whether telephone monitoring improved outcomes by facilitating engagement in outpatient care. We expected that compared with participants who received treatment as usual, participants in the telephone monitoring condition would have fewer days between discharge and first outpatient mental health appointment, would complete more mental health visits in the year after discharge, and would have higher medication possession ratios (days with completed refills of antidepressants). We also anticipated that improved treatment engagement would mediate observed differences in outcomes between study conditions.

Additional exploratory analyses examined whether the effects of telephone care management were moderated by risk factors for poor treatment engagement identified in prior studies (

29,

30). We anticipated intervention effects would be strongest among patients who previously had fewer treatment visits, lived further from care, had a less robust therapeutic alliance with their outpatient provider, and had lower treatment expectancies.

Methods

Study procedures were overseen by institutional review boards at each study site. All participants gave written consent to participate.

Participants

Veterans were recruited within two weeks of admission from consecutive admissions to five VA residential PTSD treatment programs. Patients were excluded if cognitive impairment precluded giving informed consent, if they were discharged from treatment after fewer than 15 days, or if they were transferred directly to another inpatient treatment program. Active-duty military personnel were excluded because they receive aftercare outside the VA system.

Measures

Participants completed self-report measures of all outcomes at intake to residential treatment and roughly four months and 12 months after discharge. PTSD and depression symptoms were also assessed at the end of residential treatment and before the start of the telephone intervention. PTSD symptoms were assessed with the PTSD Checklist (PCL) (

31). Aggressive behavior was assessed by using a six-item index adapted from the Conflict Tactics Scale (

32). This expands on a four-item index widely used with VA patients (

7,

9). Alcohol and drug use problems were assessed with the composite scores from the self-report version of the Addiction Severity Index (

33,

34). Depression symptoms were evaluated with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (

35). Subjective quality of life was assessed with a scale developed for the Veterans Affairs Military Stress Treatment Assessment (

36).

Rehospitalizations in a psychiatric or substance use bed section and mental health and substance use outpatient treatment visits in the year after discharge were determined from the National Patient Care Database. For patients prescribed antidepressants, medication possession ratios (days’ supply of medications divided by total days) were determined from the National Data Extracts’ pharmacy database following procedures used by Lockwood and others (

12). Distance from patients’ homes to the nearest VA clinic or veterans center was determined from VA administrative data. Therapeutic alliance with participants’ main outpatient mental health provider was determined by using the short version of the patient form of the Working Alliance Inventory (

37). Treatment expectancies were assessed by using a procedure developed by Battle and colleagues (

38).

Procedure

Participants were recruited between October 2006 and December 2009. Referring clinicians invited patients to meet with a research assistant who explained the study and obtained consent. Randomization by site, gender, and service in the recent wars in Iraq or Afghanistan was done centrally with Efron (

39) randomization by someone blind to participants’ treatment histories. Survey data at four and 12 months postdischarge were obtained by mail, with mail and telephone follow-up used to encourage participants to return the questionnaire (

40).

Treatment

After discharge, participants in treatment as usual received standard referral to outpatient counselors, psychiatrists, or both. Participants in telephone care management received standard referrals plus biweekly telephone monitoring and support during the first three months after discharge. The telephone monitoring intervention was delivered from a centralized call center by 11 clinical psychology graduate students and one social worker supervised by four clinical psychologists. Telephone monitors normally contacted patients every two weeks. If participants were unavailable on the first call attempt, the telephone monitor left a message with a toll-free call-back number and made two additional contact attempts on different days of the week at different times of day.

After three unsuccessful call attempts, participants were not recontacted until their next scheduled call. If the phone number given was no longer in service or the participant was no longer at that number, we obtained the participant’s new telephone number from a family member or friend whom the participant had provided as a contact.

When monitors reached the participant, they followed a scripted protocol to briefly assess the participant’s outpatient treatment attendance; medication compliance; severity of symptoms and coping related to PTSD, depression, and anger; substance use; suicidality; and risk of violence (

17). Severity of PTSD, depression, and anger symptoms were rated on a 10-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Participants’ overall confidence in coping with symptoms was rated on a 10-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater confidence. Participants received verbal reinforcement of positive behaviors. Participants who had a problem in any given area got interventions to address that issue, including problem-solving support or brief motivation enhancement. For example, if participants reported becoming verbally aggressive, the monitor asked whether the aggression had caused them any problems and whether they were satisfied with how they had handled their anger. If participants were satisfied, the monitor briefly reiterated the negative consequences mentioned by the participants and moved on.

If participants felt they handled the argument badly, the monitor asked the participants to generate some alternative actions they could have taken and encouraged them to discuss this concern with their outpatient provider. If participants were at risk of harming themselves or others, monitors immediately alerted their supervisor and the participants’ outpatient provider. Telephone monitors also informed outpatient mental health providers if a participant reported an increase of ≥3 points in measures of PTSD, depression, or anger symptoms.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted on an intent-to-treat basis, by using multiple imputation to address potential bias introduced by missing data (

41,

42). All analyses were conducted by using R version 2.9.2 (

43), and multiple imputations were completed with the R MICE library (

44). The sample size provided 90% power to detect small (d=.20) effects of condition on outcomes. To address our primary and secondary hypotheses, we assessed the effect of condition on clinical outcomes at four and 12 months postdischarge with regression models that included the effects of condition, site, and condition by site, controlling for baseline scores on the outcome measure and time from intake to four-month follow-up. Analyses of PTSD and depression outcomes controlled for scores at both intake to (baseline 1) and discharge from (baseline 2) residential treatment. Analyses for all other outcomes included only the intake baseline as a covariate. The effects of condition on time to rehospitalization were assessed by using Cox regression that controlled for the effects of condition, site, and condition by site.

To address our tertiary hypotheses, time to first outpatient visit was assessed by using the same Cox regression model as for rehospitalization. Regression models were used to test the effects of condition, site, and condition by site on (log-transformed) number of mental health treatment visits completed in the year after discharge and on medication possession ratios. If there were significant differences by condition in both outcomes and treatment engagement, additional analyses were conducted to test whether degree of treatment engagement mediated differences in clinical outcomes. Exploratory regression analyses tested whether there were significant interactions between each of our five moderators and treatment condition in predicting violence, alcohol problems, and drug problems at four months postdischarge and in antidepressant medication possession ratios and mental health or addiction treatment visits in the year after discharge.

Results

Of 1,025 eligible participants, 925 agreed to participate. Six participants dropped out prior to randomization, and 82 were disenrolled because they were discharged within 14 days or were discharged directly to another inpatient program. The remaining 837 participants were randomly assigned to telephone monitoring (N=412) or treatment as usual (N=425) conditions. [A figure summarizing participants’ participation at each stage of the study is available online as a data supplement to this article.] Participants’ length of stay in the programs ranged from 15 to 149 days (median=26 to 64 days). There were no significant differences in demographic or baseline clinical characteristics of participants in the two treatment conditions (

Table 1).

Telephone monitors successfully reached and completed at least one call for 86% of participants (N=355) in the intervention condition. Patients contacted by phone completed an average of 4.5±1.6 calls of six planned calls. The average call length was 16.4±10.8 minutes (range two to 113 minutes). Approximately 16% of completed calls identified an emergent issue that required phone or e-mail follow-up to patients’ outpatient mental health providers. Serious suicidal ideation was reported in 6% of calls, homicidal ideations in 6% of calls, and heavy alcohol or drug use in 5% of calls.

Our primary and secondary hypotheses, that telephone monitoring would improve clinical outcomes and extend time to hospitalization, were not supported. There were no differences in PTSD symptoms, aggressive behaviors, alcohol problems, drug problems, depression, or subjective quality of life between patients who received telephone care management and usual care at four months or one year postdischarge (

Table 2). Time to rehospitalization for psychiatric or substance use problems was similar in both conditions, with 11% (N=46) of intervention participants and 13% (N=55) of participants in treatment as usual rehospitalized within a year of discharge.

Our tertiary hypotheses that the intervention would improve engagement in care were also not supported (

Figure 1). Time to first outpatient visit was similar in both groups, with 86% (N=354) of intervention participants and 87% (N=370) of participants in treatment as usual completing a mental health visit within 30 days of discharge. In the year after discharge, patients in the telephone condition completed an average of 37.8±46.6 in-person mental health or addiction treatment visits compared with 34.4±39.9 among controls.

The only difference in utilization was for telephone visits in the first 90 days after discharge other than those delivered as part of the study. The average number of telephone visits with mental health providers was higher among patients who received telephone monitoring than among patients who received treatment as usual (3.2±4.1 and 1.3±2.8, respectively, t=8.0, df=1,831, p<.001). This reflected providers’ checking on their patients after being informed by telephone monitors that a patient was experiencing problems. Among the 758 participants prescribed antidepressants, mean medication possession ratios were similar for both groups (.60±.26, telephone monitoring, and .62±.27, treatment as usual). Exploratory analyses showed that the effects of telephone care on clinical outcomes and treatment engagement were not moderated by prior use of mental health care, distance from clinic, therapeutic alliance, treatment expectancies, or substance use problems.

Discussion

Why did telephone care management fail to improve veterans’ outcomes compared with usual care after discharge from residential treatment? We were able to successfully deliver the intervention. Three-quarters of participants received at least three of the six telephone calls intended, a dose comparable to other successful trials of telephone interventions (

21,

22). Many patients and their clinicians said that they appreciated the calls and found them helpful. Nonetheless, the intervention did not improve patients’ functioning.

Our intervention model assumed that poor compliance with aftercare contributes to veterans’ problems after discharge (

Figure 1). This assumption was incorrect. In contrast with prior reports (

1,

17), over 85% of participants completed a mental health visit within 30 days of discharge. Rather than having poor treatment attendance, veterans in this study were high utilizers of outpatient care, attending an average of one mental health appointment every ten days in the year after discharge. In this context, there was little incremental value in providing an additional telephone contact every 14 days.

Our null findings contrasted with prior studies in which telephone care management improved outcomes of patients in primary care, addiction, and psychiatric aftercare programs (

23,

24,

26,

28). In these studies, patients saw their providers infrequently and telephone care management represented a substantial increase in patient contact. That was not the case in this study. Telephone support may have stronger effects on patient outcomes in settings where there is limited aftercare (

2).

Our treatment utilization findings likely reflect VA efforts to improve continuity of care in the years since our pilot study was conducted. Between fiscal years 2000 and 2009, the proportion of PTSD patients completing an outpatient visit within 30 days after discharge from VA inpatient mental health care rose from 68% to 78% (

5,

45). During that same period, rates of rehospitalization within six months of discharge from residential PTSD treatment declined from 29% to 24%.

However, continuity of care does not ensure good clinical outcomes (

1). Many veterans in this study had continuing problems despite receiving substantial amounts of residential and outpatient care. Selection factors may be present, with more chronically impaired individuals being the most likely to be referred for residential PTSD treatment. Reliance on pension compensation could also potentially reduce veterans’ response to treatment, given that 95% of patients in VA residential treatment either receive or seek disability pensions for PTSD (

46,

47). However, empirical evidence on how compensation seeking affects treatment outcomes has been inconsistent (

47,

48).

Our findings raise questions about whether we are providing the right mix of services for chronic PTSD patients. Not all residential treatment programs, especially those with shorter lengths of stay, included evidence-based psychotherapies that directly target PTSD symptoms. Providing these treatments could enhance patient outcomes (

49).

Despite receiving a large dose of aftercare, patients showed little mean improvement in PTSD symptoms between the four-month and 12-month follow-up assessments. It is likely that most of these treatment contacts provided case management or supportive care rather than active psychotherapy (

50). There may be more efficient and effective ways of providing supportive care. There may be less need for frequent in-person appointments to monitor patient safety now that the VA has a 24-hour crisis counseling hotline. Some supportive services currently delivered during clinic visits could be provided via brief telephone contacts, peer-led support groups, or Internet or mobile phone technologies (

51,

52). These alternatives could free up more of clinicians’ time for delivering evidence-based psychotherapies that can have a greater impact on veterans’ functioning (

53).

We are unaware of any significant unintended effects or harms of this telephone intervention. Five (1.2%) participants asked to discontinue calls because of distress and four (1.0%) because of concerns about confidentiality. This study was limited to patients who sought intensive residential treatment in the VA health care system, where aftercare was readily available. Telephone case monitoring might function differently in other treatment environments.

Conclusions

Augmenting usual care with biweekly telephone care management support in the first three months after discharge failed to improve veterans’ clinical outcomes in the year after residential PTSD treatment. This is likely due to the fact that patients were already high utilizers of outpatient care in the year after discharge. Many veterans had continuing difficulties in functioning despite receiving a large dose of care. This suggests a need for more effective and efficient ways of providing continuing support to veterans living with severe and chronic PTSD.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was partially supported by grant TEL-03-135 awarded to Dr. Rosen by the Office of Research and Development, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration. It was also supported by the VA Center for Health Care Evaluation and the VA Palo Alto Health Care System. The authors thank the veterans whoparticipated in this trial as well as Eric Crawford, Ph.D., and Carolyn Greene, Ph.D., for clinical and administrative supervision; Julie Fitt, B.A., B.S., and Kathryn Kalaf, B.S., for study coordination; Douglas Anderson, M.A., Debra Boyd, M.Ed., Emerald Katz, B.A., Leslie McCulloch, Ph.D., Skye Sellars, B.A., and Samantha Tidd, B.S., for subject recruitment; and Brad Belsher, Ph.D., Allison Broennimann, Ph.D., Zeno Franco, Ph.D., Megan Goodwin, Psy.D., Erin Joyce, Psy.D., Candy Katoa, Psy.D., David Scott Klajic, Ph.D., Megan McElheran, Psy.D., Kate Marino, Psy.D., Jennifer Sweeton, Psy.D., and Seth Tuengel, M.S.W., for delivery of the telephone care intervention. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of the VA.

The authors report no competing interests.