Antipsychotics have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression—disorders that impose an enormous morbidity and mortality burden (

1,

2). These medications are used off-label for many other indications (

3). Physicians face a choice of more than 90 antipsychotic products (24 molecules and their reformulations). Six second-generation antipsychotics introduced between 1989 and 2002 rapidly became first-line treatments on the basis of claims that they were more effective and safer than first-generation antipsychotics. Second-generation antipsychotics continue to claim a majority of the market despite their higher costs (

4).

However, comparative effectiveness research findings published ten to 15 years after second-generation antipsychotics were introduced indicate that these agents pose significant risks and that, with the exception of clozapine, they may be no more effective than first-generation antipsychotics. For example, the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE), published in 2005, which compared four second-generation antipsychotics with one first-generation antipsychotic among patients with schizophrenia, found few differences among the drugs on all-cause discontinuation rates, the trial’s primary endpoint. Notably, CATIE also found that the risk of adverse effects and reason for discontinuation differed widely across the five antipsychotics (

5).

Although CATIE findings remain controversial (

6,

7), one might expect physicians to have changed their antipsychotic prescribing in response to these findings and those from other studies (

8). Before the CATIE results were published, the FDA issued safety warnings in 2003 and 2005 (

9,

10) in response to evidence of risks (

11), and consensus statements emphasized heterogeneous risk profiles across second-generation antipsychotics (

12). Prescribing preferences are also shaped by formularies and utilization management tools (

13,

14), which were used by some payers during this period (

15,

16). Little is known about whether new evidence or changes in policy led clinicians to change their preferences for certain drugs or diversify their prescribing (

17,

18). Studies of prescribing for depression and bipolar disorder indicate that physicians rely heavily on preferred agents (

19–

24) One study examined the degree of concentration in antipsychotic prescribing, but results were reported at the facility level, not at the provider level, for a single year (

25). We measured changes in physician antipsychotic prescribing behavior using data from a longitudinal cohort (2002–2007) of physicians from multiple specialties.

Methods

We used monthly physician-level data from the Xponent database, maintained by IMS Health, on the number of prescriptions dispensed for all antipsychotics between January 2002 and December 2007. Xponent directly captures over 70% of all U.S. prescriptions filled in retail pharmacies and utilizes a patented proprietary projection methodology to represent 100% of prescriptions filled in these outlets. We linked prescribing data to information on physician characteristics from the American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile (

26). These data were available for a 10% nationally representative sample of physicians from ten specialties with the highest antipsychotic prescribing volume (internal medicine, general practice, family medicine, family practice, pediatrics, psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, neurology, and child neurology) (N=24,206). We limited the 10% sample to a longitudinal cohort of physicians who regularly prescribed antipsychotics (defined as ≥20 dispensed antipsychotic prescriptions or the equivalent of two patients filling prescriptions for ten months per year) both in 2002 and in 2007. Our rationale was that very-low-volume prescribers tell us little about the diversity of a physician’s prescribing. For example, a physician who writes a single prescription is by definition 100% concentrated on that particular drug. Thus including observations for very-low-volume prescribers may yield unstable or misleading results. This reduced sample of 7,399 physicians accounted for 83% of all antipsychotic prescriptions among the 24,206 physicians in our sample in 2007. Sensitivity analyses that included the larger sample yielded qualitatively similar results.

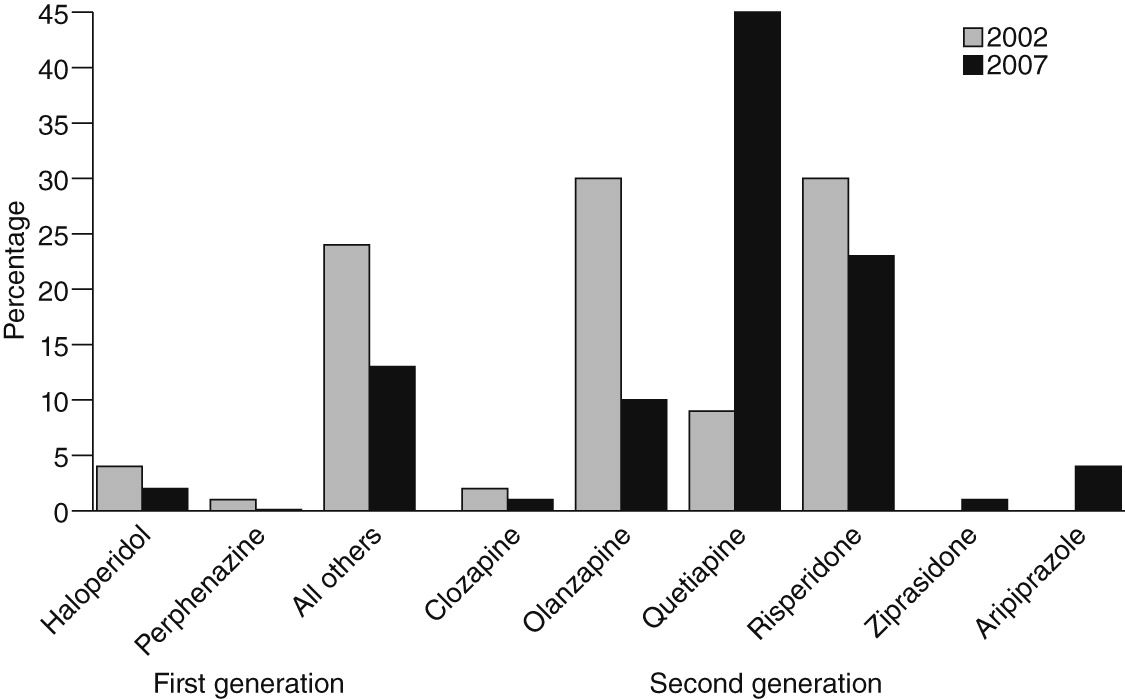

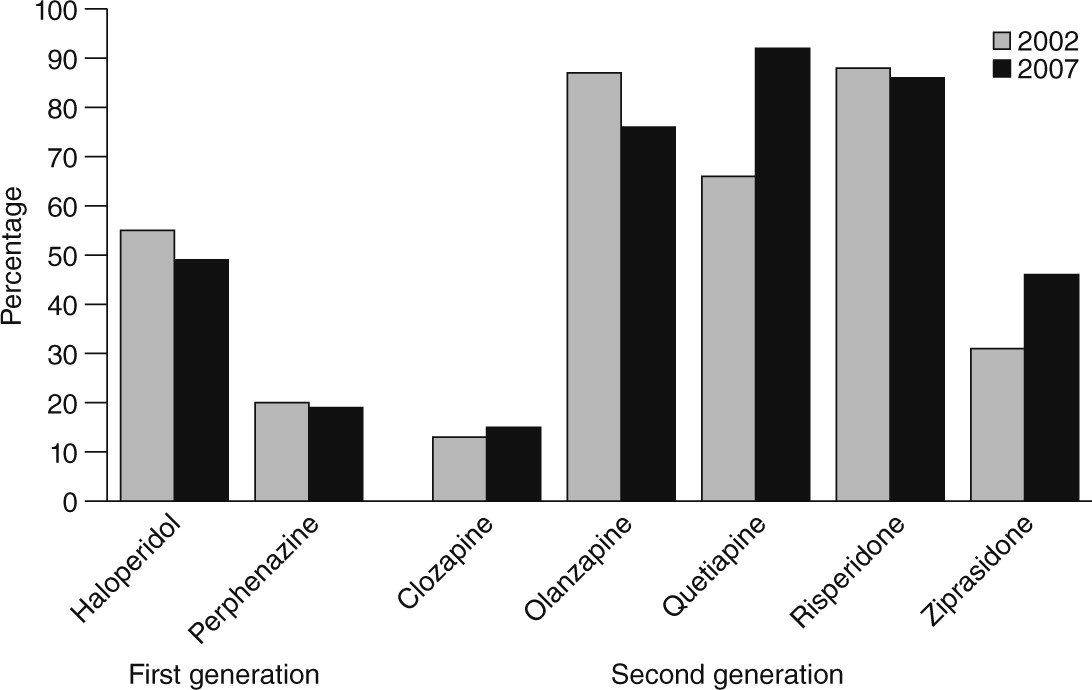

We examined prescribing patterns for six orally administered second-generation antipsychotics (clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole). Because aripiprazole was launched late in 2002 and was seldom used that year, we do not report its use separately in some analyses. We also examined prescribing of two oral first-generation antipsychotics: haloperidol, the most commonly prescribed first-generation antipsychotic, and perphenazine, because of its inclusion in CATIE. We combined other first-generation antipsychotics into a single group. Prescriptions for reformulations (for example, Zyprexa Zydis) were merged with the original ingredient (for example, olanzapine).

Dependent variables

We analyzed trends in three aspects of prescribing behavior. First, we measured the concentration of a physician’s prescribing by constructing a Herfindahl index, a metric that characterizes the degree of competition in a market. Here we use it to describe the diversity of a physician’s prescribing of antipsychotics to his or her patient population. The index is constructed as

where si is the share of prescriptions for drug i in the antipsychotic market, and N is the number of drugs in the market. The smallest possible value of H is 1/N (prescribing each drug with the same frequency), and the largest is 1 (prescribing only one drug). Notably, H is dependent on the volume of a physician’s prescribing (for example, H=1 by definition if the physician writes a single prescription), which is why we excluded very-low-volume prescribers. We hypothesized that physicians would reduce the concentration of their prescribing in response to evidence of differential side effects.

Second, we quantified changes in the specific drugs most preferred by physicians between 2002 and 2007. For each physician, we identified the drug with the most prescriptions filled in 2002 and then in 2007, yielding estimates of the proportion of physicians who demonstrated stable (or unstable) preferences over time. Third, we assessed changes in the proportion of physicians with any prescriptions for each drug in 2002 versus 2007. We hypothesized that physicians may have changed not only their preferences for but also their general use of specific agents on the basis of risk of metabolic effects, potentially reducing use of drugs with the highest risk (olanzapine and clozapine) and increasing use of drugs with intermediate risk (risperidone and quetiapine) and low risk (aripiprazole and ziprasidone) (

12). We also examined whether physicians increased their use of lower-cost agents (first-generation antipsychotics) following evidence that these agents were cost-effective relative to second-generation antipsychotics (

27).

Key explanatory variables

We examined whether changes in prescribing behavior differed by physician specialty and prescribing volume. We classified physicians based on specialty into two groups: psychiatry (general, child and adolescent, and geriatric) and “other,” which included neurologists (general and child); pediatricians; and physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine, family practice, and general practice. Notably, general practitioners and other nonpsychiatrist specialists behaved similarly on the prescribing practices we observed. To assess prescribing volume, a potential proxy for a physician’s experience prescribing antipsychotics, physicians were classified according to the total number of antipsychotic prescriptions their patients filled in 2001, one year before the study period. Physicians above the 50th percentile were considered high-volume prescribers. We included a dummy variable in the concentration analysis for the 1.8% of physicians whose patients did not fill any antipsychotic prescriptions in 2001.

Covariates

We included as covariates physician sex; age in 2002; and practice setting (solo practice; two-person; other, such as locum tenens, medical school, and inpatient attending only; or no classification available, with group practice as the reference category); whether the physician practiced in a hospital setting part- or full-time; attendance at a medical school ranked in the top 25 in 2010 by

U.S. News &

World Report; and whether the physician graduated from a foreign medical school. The final variable was included to explore any differences arising from training in other countries, where preferences for or availability of specific agents may have differed. As a potential proxy for less contact with the pharmaceutical industry, we included an indicator of whether the physician requested that the AMA withhold his or her information from pharmaceutical sales representatives. We included dummy variables for the state in which physicians practiced to account for time-invariant geographic variation in prescribing practices (

28), including Medicaid program restrictions on some antipsychotics in some states (

15).

Analyses

To examine the concentration of antipsychotic prescribing, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for repeated measurements made for the same physician each year. We used a gamma distribution with a log link function because of the skewed distribution of the Herfindahl index in our sample. We tested for differences in changes in the physician-level Herfindahl index over time by specialty or by volume by including three-way interaction terms between specialty, volume, and time (yearly indicators) and the three two-way interaction terms for these variables. In addition to these variables, the model adjusted for the other covariates listed above.

To explore the stability of preferences over time, we conducted a test of proportions comparing the proportion of physicians who preferred each drug in 2002 versus 2007.

Finally, we describe changes in the unadjusted rate of physicians’ prescription of each drug to any of their patients in 2002 and in 2007.

Discussion

We report three key findings. First, physicians’ reliance on a preferred antipsychotic agent, as measured by the concentration of their prescribing, declined between 2002 and 2007, particularly among psychiatrists. Second, clear differences were found by specialty and prescribing volume in the concentration of a physician’s antipsychotic prescribing. Third, substantial changes were noted in the antipsychotic agent most preferred by physicians. These findings have a number of implications for clinicians, researchers, and policy makers.

We measured changes in the concentration of prescribing in the wake of high-profile FDA safety warnings, consensus statements issued from professional societies, a landmark comparative effectiveness study, expanded approval of new indications and off-label use, highly publicized litigation against second-generation antipsychotic manufacturers (

29), and policy changes regarding coverage of these drugs. We hypothesized that evidence of substantial heterogeneity in risk profiles might have induced physicians to diversify their choice of agent, and we found evidence of this effect, particularly among psychiatrists. The rise in antipsychotic polypharmacy during this period may have increased the diversity of agents prescribed (

30). We found a mean Herfindahl index of .27 to .33 depending on the year, which is slightly higher than that reported for antidepressants, suggesting greater concentration in antipsychotic prescribing (

22,

24). Customizing drug treatment to individual patients requires more time and communication with patients and can impose a significant burden on physicians (

19). To reduce this burden, physicians often rely heavily on a few drugs per class (

19–

21,

23,

24,

31), an approach often reinforced in clinical pharmacology education (

32). However, heavy reliance by physicians on a few antipsychotics could be problematic for patients because of heterogeneity in their side effects.

Our finding that psychiatrists were so much less concentrated (more diversified) in their choice of antipsychotic than physicians in other specialties suggests that the capacity to customize treatment may vary by the degree of specialization, by experience, or with the severity of patient illness (

33,

34). Psychiatrists generally focus their prescribing on a few therapeutic categories, whereas psychiatric medication makes up a smaller (if growing) part of primary care physicians’ prescribing (

35). Variability in concentration may also be related to interspecialty differences in the clinical indications for use or in patient severity. Notably, the effects of specialty remained strong even after adjustment for volume differences. Given the dramatic expansion in antipsychotic prescribing in primary care settings, it is important to better understand these specialty differences (

36,

37) and their implications for the quality of pharmacotherapy for mental disorders (

38–

40).

Even after the analyses controlled for specialty, antipsychotic prescribing volume was negatively associated with concentration, suggesting that physicians’ ability to diversify medication choice may increase with experience, perhaps because the burden of customization decreases. Although a volume-quality relationship is well documented in other areas of health care, we are unaware of evidence of such a relationship for prescribing (

31).

Preferences for specific drugs changed dramatically. The antipsychotic for which the greatest decline was noted was olanzapine, and the share of physicians who prescribed any of the two first-generation antipsychotics we studied (haloperidol and perphenazine) also fell. In terms of physician preference, quetiapine showed the greatest increase. How does one explain these shifts? We were unable to tease out the effects on prescribing behavior of any single event, because all physicians were equally “exposed,” and we lacked a comparison group. However, four important factors warrant discussion. First, although metabolic effects are arguably one of the most salient issues influencing antipsychotic prescribing, the shifts in observed physician preferences cannot be entirely explained by differences in metabolic effects. Physicians increased use of one drug with intermediate risk (quetiapine) but not the other (risperidone), and a reduction in prescribing was noted for a drug with low metabolic risk (ziprasidone). Second, some shifts in preferences may have been driven by off-label use (for example, quetiapine for sleep disturbances) (

3,

41). Third, the reduction in use of first-generation antipsychotics and clozapine suggests that physicians either were unaware of or not influenced by evidence of the cost-effectiveness of first-generation antipsychotics (

27) and the greater effectiveness of clozapine for patients with treatment-resistant illness (

42). Fourth, antipsychotics are heavily promoted by the pharmaceutical industry through sales representatives, sponsorship of professional meetings, and other means (

43), which have significant effects on physician prescribing preferences (

44–

46). Unfortunately, data on the exposure of individual physicians to promotion are not available. Notably, aripiprazole has also been advertised to consumers (

43).

Our study had several limitations. First, we lacked patient-level information and therefore could not determine the reason for antipsychotic use or the severity of illness or distinguish between new treatment starts and ongoing treatment episodes. Second, although we selected our time period to coincide with key events, such as FDA warnings and the CATIE trial, other underlying factors may have had an effect on prescribing behavior, and we cannot infer a causal relationship between the release of studies or warnings and prescribing decisions. Third, our data were for prescriptions filled through retail outlets (that is, no data were included from mail order programs or long-term care facilities), and we thus could not observe changes in these settings. Furthermore, to the extent that we had data only for filled prescriptions (not for all those written), our results were confounded by factors affecting patient decisions to fill prescriptions. However, it is not likely that discrepancies between prescriptions written and filled differed systematically by drug. Finally, we were unable to adjust for some important influences on prescribing behavior, such as manufacturers’ promotional efforts. Such factors may vary by specialty, by health systems in which physicians practice, and by payers, which may shape physician preferences through formularies and utilization management tools (

15,

16).

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grants R01MH093359, P30 MH090333, and R01MH087488 from the National Institute of Mental Health; grant R01HS017695 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; and a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Investigator Award in Health Policy Research. The authors thank Hocine Azeni, M.S., for expert statistical programming. The study team had full access to all data from the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; the team had complete freedom from the study sponsors to direct analysis and reporting. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this article are based in part on data obtained under license from the following IMS Health Inc. information service: Xponent (1996–2008). The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed herein are not necessarily those of IMS Health Inc. or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities.

Dr. Berndt and Dr. Huskamp serve on the Academic Advisory Committee for the Health Services Research Network at IMS Health Inc. (uncompensated). Dr. Berndt has received research grants from Pfizer, Inc., and Sanofi. The other authors report no competing interests.