Despite the humane motivations and popularity of the CIT model, it (like other programs in these times of shrinking resources) will be scrutinized for its impact and the soundness of its approach. The research base regarding this innovation can be expanded to provide a better understanding of how the program works currently and how it might work better. There are two major gaps in the research on CITs: whether changing officers’ attitudes, knowledge, and skills translates into behavioral change, and how criminal justice–mental health partnerships affect officers’ behavior. If done well, research addressing these questions could help set informed benchmarks of success and identify evidence-based practices for CITs. Here we propose an agenda for future research on CIT effectiveness, focusing on these issues. Although some of the proposed research will be challenging or require substantial funding, it is nonetheless necessary to understand the impact of CITs to potentially improve practice in this area.

Links between training and injury prevention and jail diversion

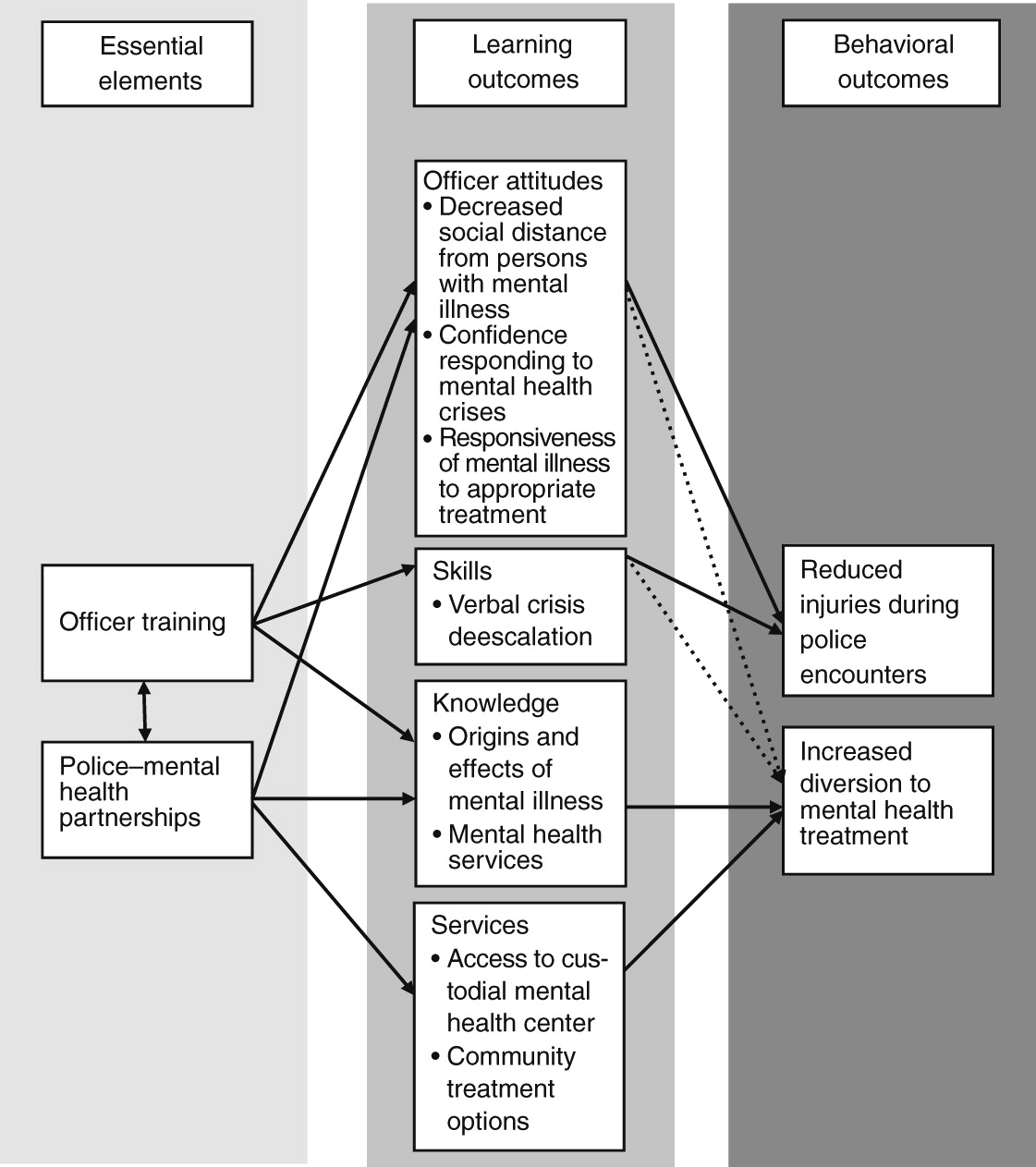

To date, it has been assumed that CIT implementation yields changes in learning outcomes, which in turn promote behavioral change on the part of officers during encounters with individuals with mental illness in the community. Whether changes in officers’ attitudes, knowledge, and skills targeted by CIT training actually lead to behavioral changes is an important empirical question at the core of the justification for the widespread implementation of this program. Yet sufficient empirical data have not been brought to bear on this question. Typical CIT training involves interactive techniques, such as role-play. Compared with professional development education, these training approaches are linked to better practice outcomes (

31). However, these approaches also show postintervention attitude changes that are much larger in magnitude than behavioral changes (

32). Studying behavioral change, in addition to attitudinal change, is thus a crucial next step for CIT effectiveness research. Research should explore each of the proposed pathways between officer training, learning, and behavioral outcomes (

Figure 1).

This is not an easy task. In addressing this question, researchers must confront the reality that many standard approaches for program evaluation will be impossible or impractical to implement. Two issues make this type of research particularly difficult: validly measuring police behavior and accounting for selection bias.

Observational data might improve the quality of measures of police behaviors; however, police encounters with individuals in a mental health crisis involve a relatively small proportion of police calls. One study in a large city observed police patrols for more than a year and found that for every 73 person-hours of observation, there was only one encounter with an individual with apparent mental illness (

33). Another analysis of two large observational studies found that just 6% of police contacts involved an individual with mental illness (

34). Therefore, collecting observational data on a scientifically sufficient number of encounters would be a lengthy process. Useful data could be obtained if on-call researchers selectively accompanied CIT-trained officers on mental health disturbance calls (identified by dispatchers) and if the data obtained from these calls could be compared with data from a sample of calls not related to mental health issues.

The alternative of using officers’ reports of incidents poses other problems. Arresting officers may not be objective informants about the circumstances that prompted them to use force or arrest. In addition, some evidence suggests that police officers tend to miss signs of mental illness in subjects (

33), so the accuracy of officers’ ratings of an individual’s mental condition might be questionable. Reports by officers can certainly be improved, possibly enough to be useful for circumscribed determinations. For example, authors of a report from the Criminal Justice and Mental Health Consensus Project (

35) recommended that officers report only observable conduct, such as incoherence, delayed response, disorientation, mania, anxiety, and hallucinations or delusions, rather than attempting to ascribe the cause of such behaviors (for example, the person is “mentally ill” or “off his meds”). These and other official records (for example, arrest and hospitalization records) could be combined to document the behavioral changes associated with CIT training, but investigators will have to capture valid encounter-level behavioral data that may not be reflected in official records.

Several other approaches might yield valid police encounter data. Follow-up interviews with both police officers and involved citizens (completed as soon as possible after the incident to maximize recall) might be used to obtain impressions of the incident (for example, how the event unfolded, level of perceived threat, use of force, and incident resolution). If time demands and caseloads allow, ratings of change in the street performance of officers obtained from their supervisors might also provide an indicator of the impact of officer training. In addition, technology has created the possibility of remote observation of police-subject interactions. Officers are increasingly wearing small cameras on their uniforms during patrol for the purposes of collecting evidence, protecting the public from police misconduct, and protecting officers from false claims (

36). Video from these cameras could be a rich source of data regarding the effects of CIT training. Using a combination of these approaches could increase the validity of reports of police behavior; none are perfect alone.

Accounting for selection bias is a second impediment to assessing the link between changes in officers’ attitudes, knowledge, and skills and their on-duty behavior. Research has generally relied on comparisons of trained volunteers (or officers selected by their supervisors for training) and untrained officers, making it difficult to separate individual characteristics (for example, predisposing temperament) from the effects of training. However, CIT developers consider officer self-selection to be one of the most important characteristics of a successful CIT program (

37). Several research strategies could address the issue of selection bias in CIT research without much disruption of departmental policies regarding selection of officers for CIT involvement. A randomized trial is not the only way to address this issue.

First, officers who volunteer for CITs could serve as their own controls. Their use of force, arrest, and treatment referral rates before and after CIT training could be compared in an interrupted time-series model. Second, the implementation of mandatory training can create natural experiments. In some smaller departments, CIT training is mandatory for all officers, and in some larger departments (such as in Houston, Texas), CIT participation is voluntary for experienced officers but mandatory for new officers (

38). In these situations, departments delivering mandatory CIT training could be compared with similar departments that have not instituted CIT training. Third, officers who volunteer could be randomly assigned to receive CIT training immediately or to wait for training. These groups could be compared on outcomes of interest during the period between training the first and second groups. Fourth, matching procedures, such as propensity score matching (

39), could be employed to account for potential differences between the voluntarily trained group and other officers. The propensity score matching approach, however, would require a large data collection effort in order to obtain enough relevant information about officers (for example, attitudes about mental illness, history of use of force, and personal relations with individuals with mental illness) to create acceptably equivalent matched groups.

Effects of CIT partnerships

Implementation of CITs varies between departments, particularly regarding the establishment of functional criminal justice–mental health partnerships. Often because of budget constraints, many municipalities focus most of their CIT resources on officer training rather than on mental health partnerships (

5,

27,

28,

37), producing an officer training intervention instead of the originally conceived systems change intervention. Whether and how the partnership with mental health providers affects the achievement of the goals of the CIT approach is an open question for future research.

It seems unlikely that officer training alone will suffice to reduce arrest of persons with mental illness (dashed lines in

Figure 1). Some districts lack a reliable system for transferring a subject into mental health custody or a facility that will admit any police-referred person who is willing to accept treatment and who does not meet criteria for involuntary hospitalization. In these districts officers are sometimes left with arrest and jail as the only option for resolving a situation (

28,

29). Officer training, even high-quality training, may not be enough to offset such organizational factors.

It has been long recognized that organizational structure and support affect officers’ behavior in the community (

40). These factors are likely pivotal to the success of CIT programs. Yet they are rarely considered when measuring CIT effectiveness (the study by Watson and others [

5] is an exception). Future studies of CITs could examine organizational factors as possible moderators of the success of officer training, providing valuable information about how context fuels success. Future work could include a qualitative assessment of political, economic, social, and personnel issues that facilitate or impede implementation efforts (from both the criminal justice and mental health sectors). At a more basic level, studies should carefully report exactly what was implemented under the CIT program, including the training elements delivered, characteristics of trained versus untrained officers, and contextual information regarding criminal justice–mental health relationships. Across multiple studies, this level of detail would build a knowledge base about implementation characteristics associated with success.

Comparative community studies would be useful if they could test clearly formulated hypotheses about how CIT-trained officers apply their training differently in method or quantity in locales with strong or weak mental health partnerships (the determination of which would require attitudinal surveys across both the mental health and criminal justice sectors). The application of attitudes, skills, and knowledge might be affected by perceptions about available alternatives or likely personal risk from taking certain actions. In pursuing this agenda of basic descriptive, quasi-experimental research, investigators could identify aspects of an organization’s culture or practices that promote the successful translation of training principles into desired behaviors of officers.

There is much room for productive research across jurisdictions. For example, research could examine arrest rates of persons with mental illness in localities where strong criminal justice–mental health partnerships are facilitated by a program other than the CIT model (Los Angeles, for example). Such research could illustrate how CIT training and organizational practices might make independent or synergistic contributions to achieving fewer arrests and more frequent appropriate jail diversion for individuals with mental illness. It might also be possible to capitalize on recent advances in geographic information systems mapping to examine how the built environment of mental health crisis services that is available to law enforcement within a jurisdiction affects practice (

41). Combining data regarding officers’ perceptions of the number and location of jail alternatives and these objective indicators could clarify some of the processes related to service referral patterns. For instance, difference scores (objective options minus perceived options) may be an important component for understanding encounter disposition and could highlight an area for officer training. The effects of organizational and community context on achieving the goals of the CIT model are greatly underexplored, even though they are assumed to be a central component of success for these efforts.