Depression is a costly chronic condition affecting 9% of adults in the United States, 4% of whom meet criteria for major depression (

1). Veterans may be at increased risk of depression compared with the general population (

2,

3). Effective treatments for depression exist, and clinical guidelines recommend use of antidepressants and psychotherapy as the standard of care (

4). Nevertheless, rates of treatment for depression are low, particularly among older adults and underserved racial-ethnic groups (

5).

Several gaps in knowledge about disparities in depression care in the veteran population exist. First, many previous studies have focused on either patients with new-onset depression or all patients with depression, regardless of duration. In addition, most guidelines address the initiation of depression care rather than ongoing care. Less is known about the large group of veterans with chronic depression. Second, various studies have used rates of receipt of antidepressants to determine quality of care and have paid less attention to psychotherapy, even though treatment guidelines recommend either or both modalities. Third, most studies evaluating treatment have compared a few racial-ethnic groups—such as black veterans compared with white veterans—which provides an incomplete picture of depression care for veterans from other minority groups (

5). This study aimed to characterize differences in treatment for multiple racial-ethnic groups of veterans with ongoing depression, examining rates of both antidepressant and psychotherapy use.

Results

We identified 62,095 veterans with chronic depression whose medical records were reviewed by EPRP in 2009 and 2010 (

Table 1). Of these, 72% were white, 16% black, 4% Hispanic, 2% Asian, 2% AI/AN, and 4% unknown racial-ethnic group. Most patients were male (71%), and most were exempt from copayments (88%). For the six-month period after the most recent depression visit, 51% of patients received adequate antidepressant care, 13% attended at least six psychotherapy sessions, and 57% received guideline-concordant care.

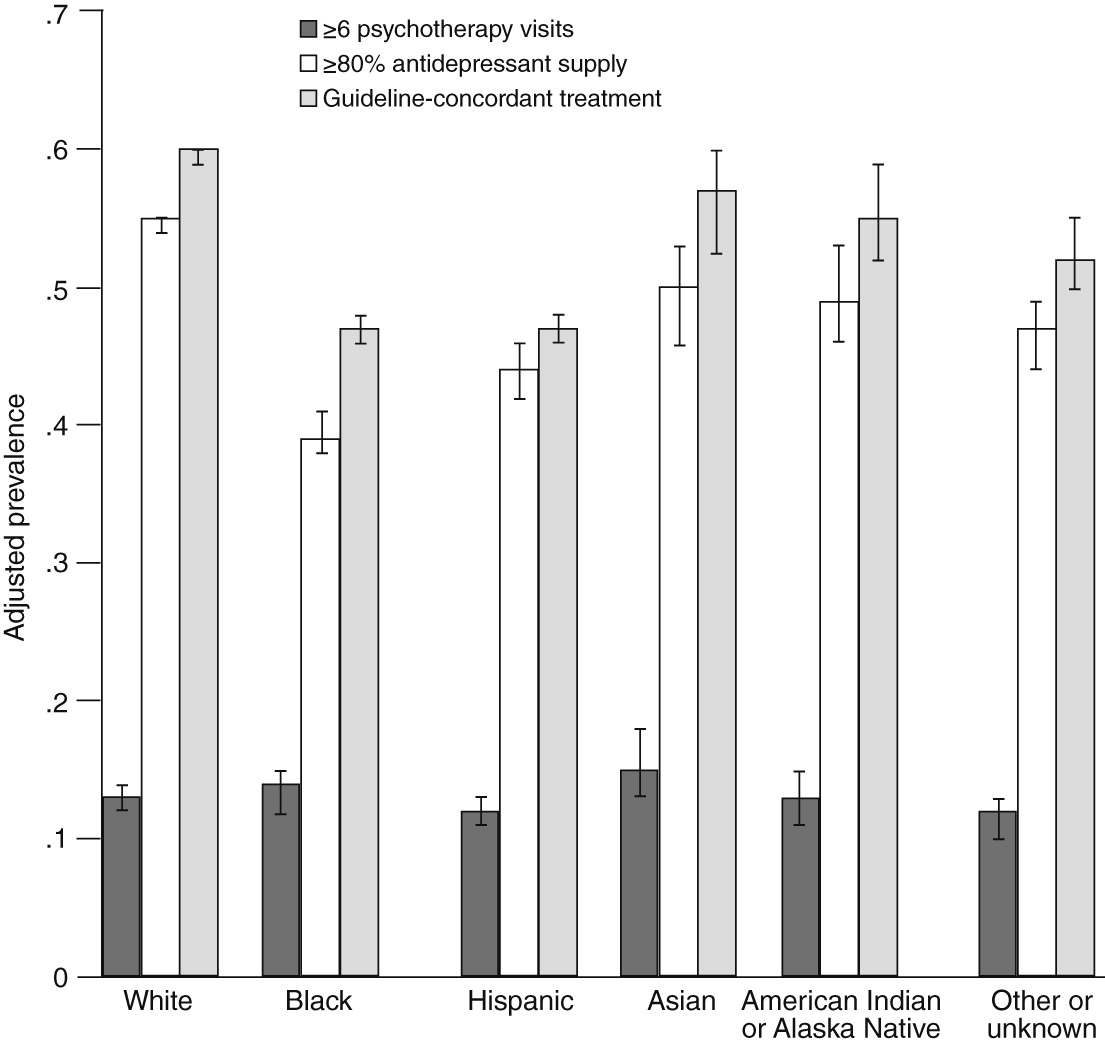

Table 2 presents unadjusted and adjusted results for logistic regression models for adequate antidepressant therapy (model 1), adequate psychotherapy (model 2), and guideline-concordant treatment (model 3). For adequate antidepressant therapy, the unadjusted and adjusted iterations (with and without accounting for distance to the parent VA facility) yielded similar results. The adjusted models reflected slight attenuation of the effects, but overall, minority groups had lower odds of receiving adequate antidepressant therapy compared with white veterans (adjusted model with distance to the parent VA facility, black OR=.53; Hispanic OR=.65; Asian OR=.82; and AI/AN OR=.80). The adjusted prevalences reported in

Table 2 also showed significantly lower adequate antidepressant therapy for veterans from minority groups compared with white veterans.

In contrast to the findings for antidepressant therapy, veterans from racial-ethnic minority groups had significantly higher unadjusted odds of receiving adequate psychotherapy (attending at least six psychotherapy sessions in the defined six-month window) (black OR=1.52; Hispanic OR=1.18; Asian OR=1.51; AI/AN OR=1.29). When we adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, health behaviors, and health status factors, the odds were attenuated, although they remained significantly higher for black veterans (OR=1.20) and Asian veterans (OR=1.32). However, once we adjusted for distance to the parent VA facility, no differences in receipt of adequate psychotherapy were observed between black and white veterans, but differences remained between Asian and white veterans (Asian OR=1.26).

Results for model 3 showed differences by racial-ethnic group in the receipt of guideline-concordant care. Overall, findings were attenuated in the adjusted versions of the model. Both adjusted iterations—with and without distance to the parent VA facility—yielded similar numerical and statistical results. Black, Hispanic, and AI/AN veterans had lower adjusted odds of receiving guideline-concordant care relative to whites (adjusted model with distance to parent VA facility, black OR=.59; Hispanic OR=.66; and AI/AN OR=.83). However, Asian veterans were as likely to receive guideline-concordant care as whites.

Figure 1 summarizes the adjusted prevalence results for receipt of adequate antidepressant therapy, adequate psychotherapy, and guideline-concordant depression care across racial-ethnic groups. Relatively low levels of adequate psychotherapy were found across all racial-ethnic groups. White veterans had the highest adjusted prevalence of adequate antidepressant therapy and guideline-concordant depression care. Black veterans had the lowest adjusted prevalence of adequate antidepressant therapy, and black and Hispanic veterans had nearly identical levels of guideline-concordant depression care, which were lower compared with the other groups.

Discussion

This study used data from a large patient database of chronically depressed veterans to examine differences in the receipt of depression care between multiple racial-ethnic groups. In adjusted models, we found significant differences between racial-ethnic groups. Rates of adequate antidepressant therapy and guideline-concordant depression care were lower for almost all nonwhite groups than for whites. Our finding of lower overall rates of guideline-concordant care could be interpreted as evidence of the existence of a disparity in the quality of depression care that black, Hispanic, and AI/AN veterans receive compared with white veterans, as might happen if clinicians were less likely to treat depression among racial-ethnic minority groups. However, the results may not necessarily imply a disparity in the quality of depression care received by veterans. First, reliance on a composite outcome, such as guideline-concordant treatment for depression, may be misleading. Our findings for guideline-concordant care were largely driven by the racial-ethnic differences in antidepressant therapy that persisted even after the analysis accounted for differences in health, socioeconomic, and geographic variables. These findings lead us to question the utility of a combined metric when greatest insight is gained from examining receipt of adequate psychotherapy and adequate antidepressant therapy separately.

Second, patients from racial-ethnic minority groups may be reluctant to take antidepressants, after these medications are recommended, prescribed, or initially tried (

31). We were not able to ascertain providers’ attempts to prescribe antidepressants or whether patients refused them. Additional research is needed to clarify the full context of patients’ preferences for depression treatment across racial-ethnic groups.

Third, we found that in unadjusted analyses, receipt of psychotherapy was more common among nonwhite veterans. Whereas black, Hispanic, Asian, and AI/AN groups all demonstrated lower odds than whites of adequate antidepressant therapies, these minority groups all had significantly higher odds than whites of receiving psychotherapy treatment. The divergent racial-ethnic patterns seen in psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are consistent with previous research (

10,

11), which focused solely on black and white veterans. The findings for psychotherapy could suggest that veterans from minority groups may more often request or be offered psychotherapy or be more amenable to it than white veterans. The findings may also point to a greater preference for psychotherapy (in lieu of medications) among certain racial-ethnic groups.

Unlike previous analyses, which did not adjust for geographic factors, our study found that the differences between racial-ethnic groups in receipt of psychotherapy were not significant once we accounted for distance from the patient’s residence to the VA facility where the depression diagnosis was given (parent facility). This finding suggests that geographic factors may account for divergent receipt of psychotherapy. It is also worth noting that the overall prevalence of psychotherapy in this study was relatively low for all racial-ethnic groups. Together, these findings suggest that veterans living further away from VA facilities may encounter particular difficulties in accessing VA mental health providers for face-to-face psychotherapy care. These findings may suggest the need for VA to augment access to psychotherapy to rural veterans. For instance, telehealth interventions have the potential to reach veterans regardless of distance to a parent VA facility, provide acceptable mental health care, and decrease rates of psychiatric hospitalizations (

32–

34). Telehealth may be a way to invest in the delivery of mental health services to provide greater access for patients and care that is acceptable across various racial-ethnic groups.

This study had several limitations. A general limitation of relying on quality assessment and administrative data is the limited number of control variables available. However, our data allowed the examination of behavioral, socioeconomic, and demographic factors, an improvement over many VA studies. Second, the data included only clinical encounters within the VA, whereas veterans may have received psychotherapy or antidepressants outside the VA. However, recent efforts to increase access to mental health services—such as by integrating mental health care into primary care settings and requiring primary care clinics to conduct mental health screening—has enabled many veterans to receive all or most of their mental health care in the VA (

35). Thus receipt of outside care is unlikely to be a significant factor driving the differences in depression care between racial-ethnic groups. In addition, because of low copayments, most veterans fill medication prescriptions through the VA pharmacy, which were captured in our analyses.

Third, although we were able to ascertain details about diagnoses and receipt of care, we could not determine additional details about how patients and their providers opted to treat or not treat depression. For instance, providers may have offered antidepressants or psychotherapy only to have patients refuse them, or symptoms may have resolved often enough that ongoing treatments were considered unnecessary. There may also be differential rates of diagnosing depression between racial-ethnic groups, particularly for patients being seen for other serious or chronic mental and general medical problems (for example, substance use disorders). This selection bias could confound the measurement of adequate treatment.

We were not able to ascertain severity of depression diagnosis with our data. Treatment recommendations and guidelines for care are contingent on the severity of the depression episode. Whether depression severity varies significantly between racial-ethnic groups remains an important consideration in the interpretation of these results and warrants further investigation. Finally, race-ethnicity data in VA patient records has been criticized as lacking in completeness (

22). Recent efforts have led to vast improvements in VA information on race-ethnicity, raising completeness in VA records to 85% across all veterans (

36). Still, analyzing large and heterogeneous racial-ethnic categories is not optimal. Future research should take within-group differences into account when examining depression treatment differences.

It is critical to identify and remediate racial-ethnic disparities in care, especially when improved care can reduce suffering and improve quality of life (

5). Although our findings suggest that racial-ethnic differences may persist in the VA at a level similar to that found in 2003 (

10), the study did not clearly identify a disparity in the quality of mental health care that veterans from minority groups received. It is possible that observed differences in treatment arose from patient-centered preferences for care and not from provider nonadherence to best-care practices for their patients from minority groups. In other words, there may have been unexamined factors that influenced receipt of care that do not constitute a disparity in depression treatment for racial-ethnic minority groups. For instance, recent research about attitudes and cultural beliefs toward antidepressant use among older black adults raises interesting considerations about patient preferences for depression care (

37). Cultural beliefs and attitudes toward specific treatment modalities may also have a bearing on the mental health care–seeking behavior of racial-ethnic minority veterans.

Future research concerning disparities in depression care should examine preferences for treatment as well as receipt of treatment and should try to identify treatment attempts made by providers in addition to use of treatments. In addition, analyses of psychotherapy use should account for geographic barriers, especially distance to the parent facility where a veteran receives depression care. Ultimately, equitable depression treatment will consist of care that is clinically effective and that at the same time offers patients the sorts of treatments they want in ways that are both acceptable and accessible.