Participants

Police officers (N=586), including both CIT-trained (N=251) and traditional officers without CIT training (N=335), were recruited from six police departments in Georgia. As described in a companion article (

16), each department had implemented CIT training of officers with local instructors and a standardized 40-hour curriculum, which was developed and made available through a statewide CIT initiative (

14). Self-selection (volunteering) for CIT specialization is commonly considered a core element of the CIT model. The percentage of participating CIT officers who reported having volunteered for CIT training (rather than having been assigned to it) ranged from 36% to 100% across the six departments (N=171, or 68% of the 251 CIT officers).

After hearing about the study through roll-call presentations, e-mail notices, flyers posted in department precincts, or word of mouth, officers with or without CIT training who were interested in participating called the research team to register for one of 34 proctored, group-based, in-depth survey administrations between April and October 2010. Between six and 29 officers participated in the survey groups. Officers took part during off-duty hours and were compensated to remunerate them for travel time to and from the assessment, approximately three hours of survey participation, and parking.

The mean±SD age of the 586 officers was 37.0±8.7 years. Participants had been officers for an average of 10.0±7.7 years. Nineteen percent of participants (N=114) were women. Sixteen percent (N=95) were high school graduates, 40% (N=237) had completed some college, 10% (N=58) had an associate’s degree, 26% (N=150) had a bachelor’s degree, 6% (N=34) had a master’s degree, and 2% (N=12) did not specify. Thirty-five percent (N=203) self-identified as African American; 59% (N=347) as Caucasian and non-Hispanic; 3% (N=20) as Hispanic; and 1% each as Native American or Pacific Islander (N=8), Asian (N=4), or other or did not specify (N=4). Among the 251 CIT-trained officers, time since training varied from less than one month to more than seven years (median months since training was 22). For half of the CIT-trained officers (N=126), time since training was between seven and 36 months. For subsequent analyses, participants were coded 1–5 for the first to fifth quintiles of time since training.

Procedures and measures

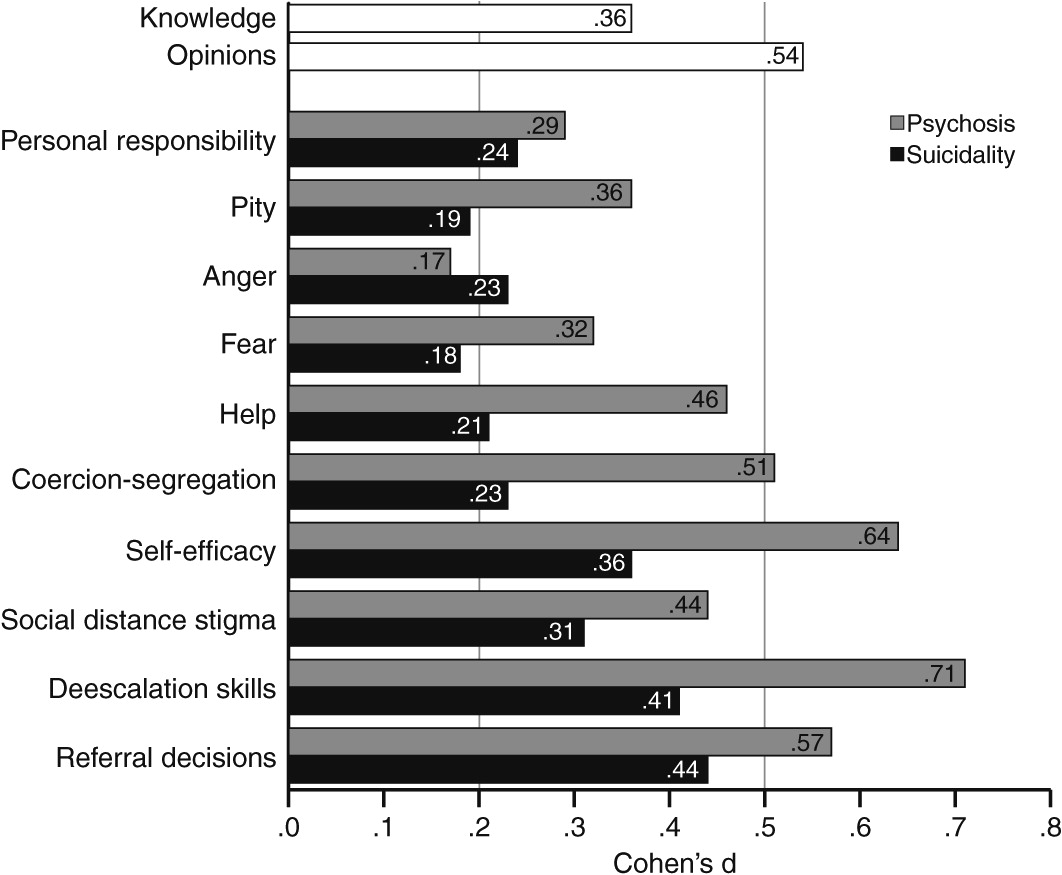

Survey administration required approximately three hours. About a third of the survey focused on demographic characteristics, experience, empathy, knowledge, and attitudinal factors. The remainder focused on attitudinal and behavioral responses to two vignettes, one written and one video, which were developed (the videos were professionally produced) specifically for this study. Groups of officers received one vignette in a video format and the other as a written script, in a counterbalanced manner. One vignette (4.2-minute video) depicted an agitated, disheveled, disorganized, and psychotic man digging through a trashcan outside a business establishment, with an officer arriving on the scene (herein called the “psychosis vignette”). The other vignette (2.5-minute video) presented an intoxicated and suicidal woman who was distraught because of a relationship break-up and who had locked herself in her home bathroom, with an officer arriving on the scene (the “suicidality vignette”). The study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board, and participants provided written informed consent.

With regard to the in-depth assessment, all constructs were scored as the mean of items answered if responses were given for at least 75% of items, except for experience with mental health treatment and knowledge about mental illnesses. Reverse scoring was conducted as appropriate, so that higher scores for all measures represent more of the named attribute.

The first portion of the assessment included a number of measures not linked to vignettes. To assess experience with mental health treatment, three items asked whether the participant (“self”), a family member, or a friend had received or was now receiving mental health treatment and a fourth items asked whether the participant, a family member, or friend had volunteered or worked in the mental health field (“other”). We created an experience index, coded 0–5, to summarize these four items: 0 if the participant responded negatively to all four items (N=193, 33%), 1 for an affirmative response only for “other” (N=64, 11%), 2 for an affirmative response for a friend but not for a family member or “self” (N=94, 16%), 3 for an affirmative response for a family member but not for friend or “self” (N=59, 10%), 4 for an affirmative response for both a family member and a friend (N=94, 16%), and 5 for an affirmative response for “self” (N=82, 14%).

The construct of empathy toward individuals with mental illnesses, which served as a potential personality-related covariate, was assessed with an adapted version of a nine-item measure (

17). Respondents are asked to “indicate how much you feel each emotion toward people with mental illnesses”; each item (for example, compassion, disgust, and respect) is rated 0, not at all, to 10, extremely (Cronbach’s α=.78). To measure knowledge about mental illnesses, officers completed the 33-item Knowledge of Mental Illnesses Test (

18), scored as the percentage of correct items.

Several measures were administered to thoroughly assess the construct labeled attitudes about mental illnesses and their treatments. The Opinions About Mental Illnesses Scale (

19,

20) consists of five subscales: authoritarianism (scored such that high scores indicate less authoritarianism), benevolence, mental hygiene, social restrictiveness, and interpersonal etiology (Cronbach’s α=.69, .63, .42, .72, and .75, respectively). Two additional scales assessed attitudes about community mental health treatment facilities (

21,

22) and attitudes about psychiatric treatments more broadly, in addition to hospitals and community facilities (

23) (Cronbach’s α=.83, and .72). The six reliable scales (excluding mental hygiene) were intercorrelated (mean r=.57, range=.29–.67). Accordingly, an “opinions about mental illnesses” variable was computed as the mean of these six scales (items for all scales were rated 1–6) (Cronbach’s α=.84).

All remaining measures were administered twice, linked to the two vignettes. Two rating scales pertained to the attitudes construct. The Attribution Questionnaire (

24,

25) consists of 21 items in six domains (for example, personal responsibility, pity, and anger). The 12-item Revised Causal Dimensions Scale (

26–

28) assesses causal attributions along four domains: external control, personal control, locus of causality-internality, and stability. The latter two domains had unacceptably low internal consistency and were not considered further. The mean Cronbach’s α for these eight attitudinal domains was .76 when linked to the psychosis vignette (range=.59–.87) and .78 with respect to the suicidality vignette (range=.62–.87).

The construct of self-efficacy for deescalating crisis situations and making referrals to mental health services was measured with a 16-item questionnaire that was rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1, not at all confident, to 4, very confident (

23) (Cronbach’s α=.94 when linked to both vignettes). To measure the construct of stigma toward people with mental illnesses, we used two instruments—an adapted version of the Social Distance Scale and a semantic differential measure. On the former, participants rated their willingness to be close to (for example, live next door to) the individual depicted in the vignette on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1, very willing, to 4, very unwilling (

23) (Cronbach’s α=.92 when linked to both vignettes). For the second stigma measure, respondents rated an average person, the man in the psychosis vignette, and the woman in the suicidality vignette on 12 semantic differentials (for example, valuable/worthless) using a rating scale from 1 to 7. The 12 items were scored so that higher values reflected more positive judgments (Cronbach’s α=.86, .83, and .84 for the three persons rated, respectively). A score reflecting total stigmatizing attitudes toward the man with psychosis was computed by subtracting the mean score on the psychosis vignette from the mean score for the average person; the same method was used for the suicidal woman. To make all values positive, 4 was added to each score, resulting in an index varying from just above 0 to just below 9.

Finally, the two constructs of deescalation skills and referral decisions were measured by two instruments designed specifically for this study and tested previously in an independent sample of nearly 200 officers (

23). Both were eight-item instruments assessing officers’ opinions about the effectiveness of specific actions in the two situations depicted; responses were rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1, very negative, to 4, very positive.