Persons with serious mental illnesses are overrepresented in jails and prisons (

1), and some of their charges likely stem from officers’ misinterpretation of disorder-related behaviors (

2). The criminalization of serious mental illnesses may be partly a manifestation of insufficient training on the front lines (

3,

4). During patrol duties, law enforcement officers, who often take on a mental health triage role, encounter many persons with serious mental illnesses (as well as alcohol and drug problems and developmental disabilities). Most officers are unaware of the signs and symptoms of mental illnesses and available resources (or they lack confidence in the latter). Therefore, they might arrest subjects rather than refer them to psychiatric services, even when arrest is discretionary— perhaps viewing individuals as responsible for their illnesses or better off separated from the community (

5). (For brevity and consistency with common policing terminology, we use “subject” to denote the individual with whom the officer interacts.) Recognition of criminalization has prompted the implementation of jail diversion programs nationwide (

6). The crisis intervention team (CIT) model, based on the original Memphis program (

7), has become increasingly popular among law enforcement agencies as a means of prebooking jail diversion.

The CIT model is a collaborative effort among the law enforcement, advocacy, and mental health communities, designed to improve outcomes of encounters between individuals with serious mental illnesses and the police. Key goals are improving the safety of the officer and the subject, minimizing use of force, and facilitating referral to treatment in lieu of incarceration, when appropriate. A fundamental aspect of the CIT model is a 40-hour training that provides officers with knowledge and techniques essential to identifying signs and symptoms of mental illnesses, deescalating crisis situations, and making appropriate dispositions. Because officers’ decision making is shaped by both formal and informal rules applied to address each encounter’s unique characteristics (

8), CIT training may shift dispositional decisions when arrest is not obligatory.

Although enhanced knowledge and attitudes, reduced stigma, and improved self-efficacy and skills among CIT-trained officers have been reported (

9–

11), little is known about their use of force and dispositional decisions. In this study of officers’ encounters, we first examined the effects of CIT training on seven levels of force and three dispositions (resolution at the scene with no further action, referral to services or transport to a treatment facility, or arrest). We then assessed how level of force was related to disposition and whether that relation was affected by CIT training status. A third, exploratory set of analyses described how CIT training status affected disposition separately in four subsamples based on subjects’ suspected condition.

Methods

Participating law enforcement agencies and officers

This report is based on a sample of police encounters that occurred in Georgia from March to November 2010. To increase both the size and representativeness of the sample, we engaged six diverse, though primarily urban and suburban, law enforcement agencies (

Table 1) that had implemented CIT within three to five years of the study and that had a relatively high percentage of CIT-trained officers among their sworn personnel (from 12% in Atlanta to 40% in Savannah).

We analyzed reports of 1,063 encounters provided by 180 officers (91 with CIT training and 89 without). The modal number of encounters reported per officer was four, and the number submitted did not vary significantly by CIT training. Initially, 586 officers who earlier had participated in a study of CIT training’s effects on officers’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills (

12) were invited to participate; 397 (68%) enrolled. Written informed consent was obtained through a process approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board, and these officers received a booklet containing 30 encounter forms and were asked to “complete a form for every interaction with a person who you think has a serious mental illness, alcohol or drug problem, or developmental disability” during a six-week period. A total of 180 officers (45%) returned a booklet with at least one completed encounter form. Data were reported for 1,063 encounters, although some data were missing for some encounters (see below).

Encounter form and encounter variables

The encounter form was developed after reviewing literature and forms used for reporting by various CIT programs. After initial development, the form was refined through two waves of review by police officers, CIT program coordinators, and others. The resulting form, a doubled-sided page consisting mostly of check-boxes, can be completed in one to two minutes.

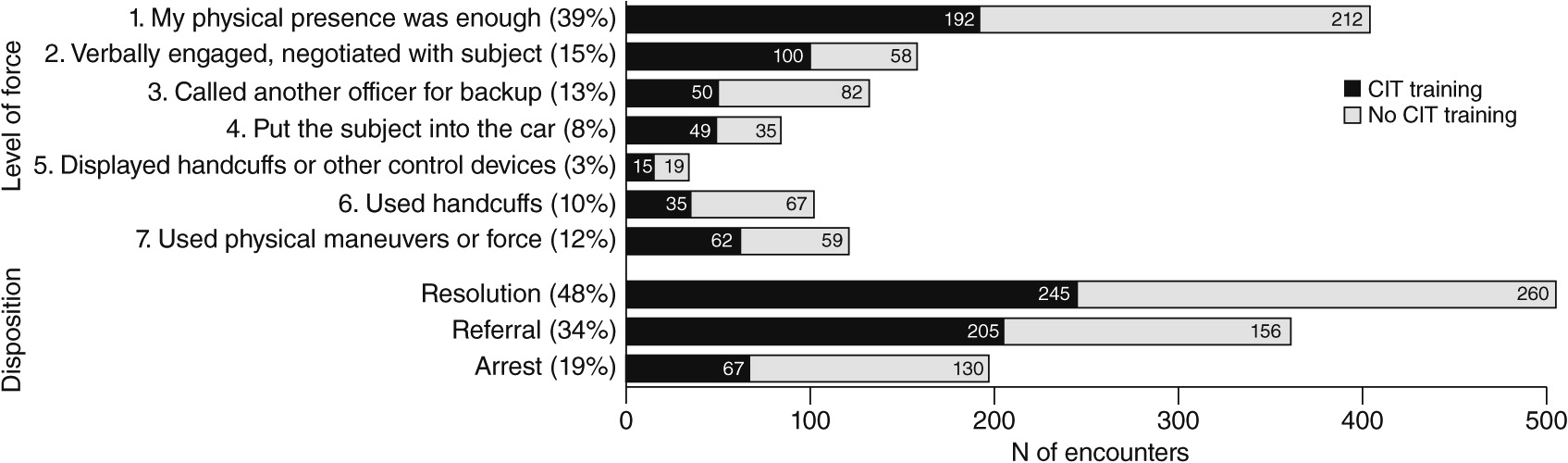

The primary variables derived from the encounter form for this report were level of force and disposition. For level of force, officers checked which of several techniques or equipment was used (no level of force was checked for 28 encounters; N=1,035) We defined seven levels of force and coded each encounter by the highest that applied. Thus level 1 was coded if the officer checked only “My physical presence was enough” (N=404 encounters, 39%) and level 7 if the officer checked “I pushed, hit, grabbed, or otherwise physically engaged the subject” or used physical maneuvers (for example, soft or hard empty hands) or devices to handle the situation (N=121, 12%).

For disposition, encounters were coded as resolution at the scene with no further action (N=505, 48%), referral to services or transport to a treatment facility (N=361, 34%), or arrest (N=197, 19%). Disposition was recorded for all encounters (N=1,063).

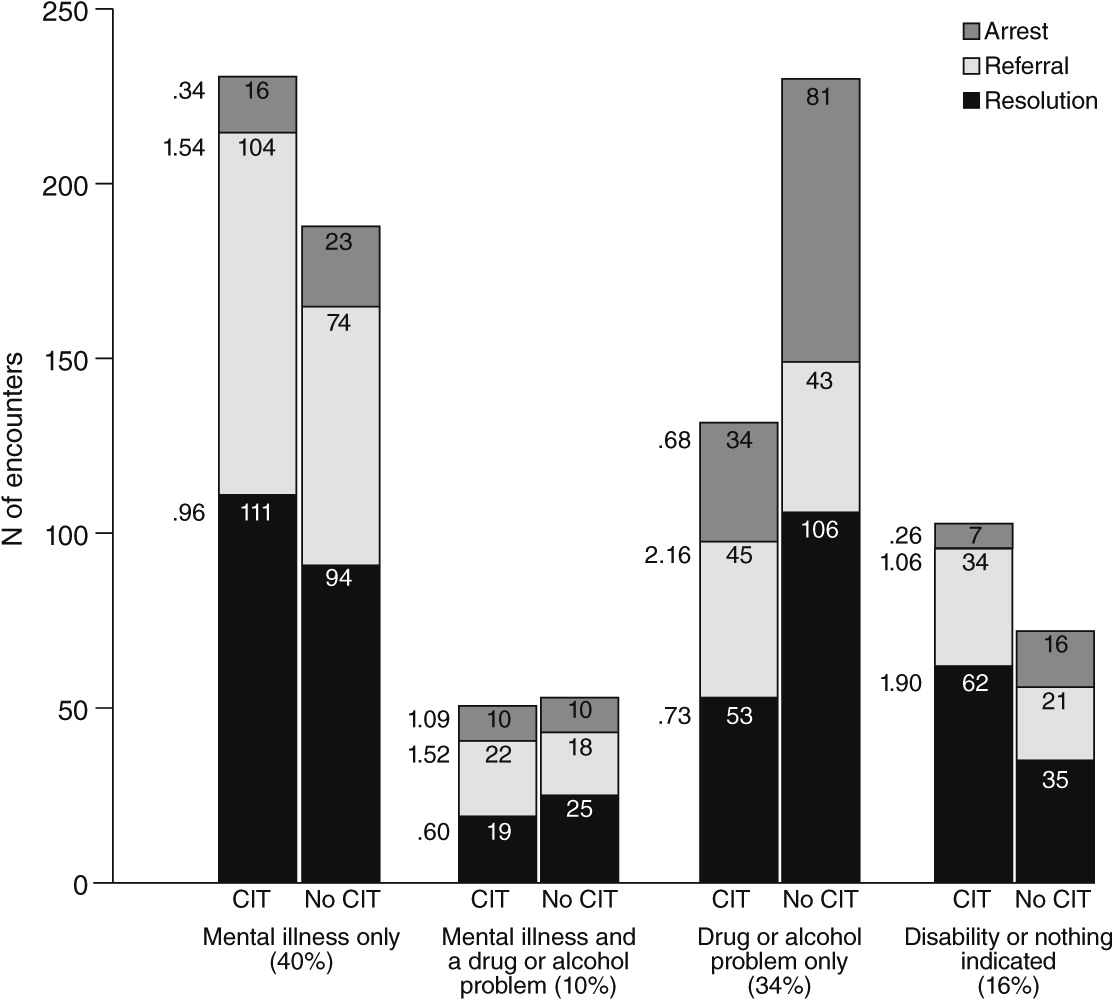

Officers also recorded whether the subject was suspected to have a serious mental illness, a drug or an alcohol problem, or a developmental disability (they could check more than one). We defined four subsamples: mental illness only (N=422, 40%; including 24 encounters in which developmental disability was also checked), mental illness plus a drug or an alcohol problem (N=104, 10%; including eight encounters in which developmental disability was also checked), a drug or an alcohol problem only (N=362, 34%; including eight encounters in which developmental disability also checked), and disability or nothing indicated (N=175, 16%; including 82 encounters in which only developmental disability was checked and 93 encounters in which nothing was checked). We pooled the final two groups because analyses suggested that they did not differ meaningfully with respect to our primary variables.

Statistical analyses

We used SPSS, version 18, to recode and examine distributional properties of variables. Descriptive statistics are reported primarily in percentages. Odds ratios (ORs) were used to characterize effects of officers’ CIT training status. Because encounters were nested within officers, ORs were estimated with MPlus, version 6.1, which accommodates multilevel models, including those with binary outcomes. These ORs are >1 when the CIT percentage is higher than the non-CIT percentage and <1 when it is not. Generally, ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) excluding 1 (no effect) are interpreted as significant. However, CIs of quite small or quite large ORs may fail to exclude 1 when cell numbers are small (that is, low power). In such cases, a useful guideline is that OR values ≤.33 or ≥3.00 indicate strong effects, >.33 but ≤.50 or ≥2.00 but <3.00 indicate medium effects, and >.50 but ≤.80 or ≥1.25 but <2.00 indicate weak effects (

13).

Discussion

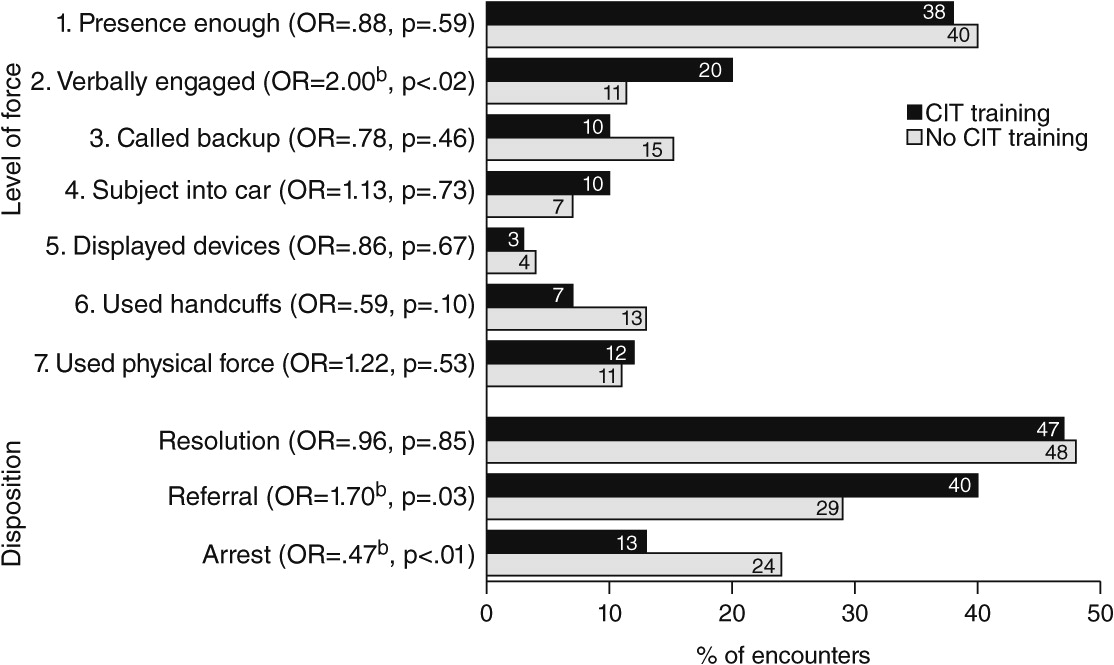

Several new findings emerged from this study. With regard to level of force, it is noteworthy that only 12% of encounters escalated to the level of physical maneuvers or force and that there was no difference in use of force between officers with CIT training and those without it. A probable explanation for this finding is that use of physical force is driven primarily by the violence potential of the encounter and the subject’s level of resistance, as has been shown in prior research (

14), as well as by officers’ standard training and by policies on the force continuum, in which the officer’s response is driven by the subject’s resistance (

15). Morabito and colleagues (

16) reported that among 216 officers in four police districts in Chicago, subjects’ physical resistance was the strongest predictor of force (OR=20.15). However, an interaction was found between the officer’s CIT status and the subject’s resistant demeanor, such that CIT-trained officers were less likely to use force than officers without CIT training as the subject’s demeanor became more resistant.

Although use of physical force in our study did not differ between officers with or without CIT training, one of the seven levels did differ. Specifically, for 20% of encounters involving CIT-trained officers, the highest level of force used was verbal engagement or negotiation with the subject, whereas this was the highest level of force used in only 11% of encounters involving officers without CIT training. This difference suggests that the 40-hour CIT training, which focuses heavily on experiential and role-play training in verbal deescalation, enhances officers’ use of these techniques in encounters. A previous survey-based study (

17), in which participants responded to a vignette describing an escalating scenario involving a man with psychosis, demonstrated that compared with officers who had no CIT training, CIT officers opted to use less force and perceived physical force to be less effective and nonphysical actions to be more effective. The findings of that study and other CIT studies, along with the findings reported here, indicate that the CIT model has an impact on officers’ actions and use-of-force decisions, although in complex ways.

Regarding encounter dispositions, referral to services or transport to a treatment facility was significantly more likely and arrest was significantly less likely when encounters involved CIT-trained officers. Steadman and colleagues (

18) initially reported a lower arrest rate for a CIT program compared with other models (community service officers and a mobile crisis unit). Teller and coworkers (

19) documented an increased rate of transport of persons in mental health crisis by CIT-trained officers. Watson and colleagues (

20) found that compared with their peers with no CIT training, CIT-trained officers in Chicago resolved a greater proportion of calls involving persons with mental illnesses by linking them to mental health services; however, they found no difference in arrest rates. In the CIT model, a core element is a designated emergency mental health drop-off site (or multiple sites) with a no-refusal policy, which is key to improving officers’ willingness and ability to access services (

21,

22). Thus the 40-hour training likely works in conjunction with other elements of the CIT model to bring about desired outcomes, such as increased referral and diversion from arrest and incarceration to mental health services.

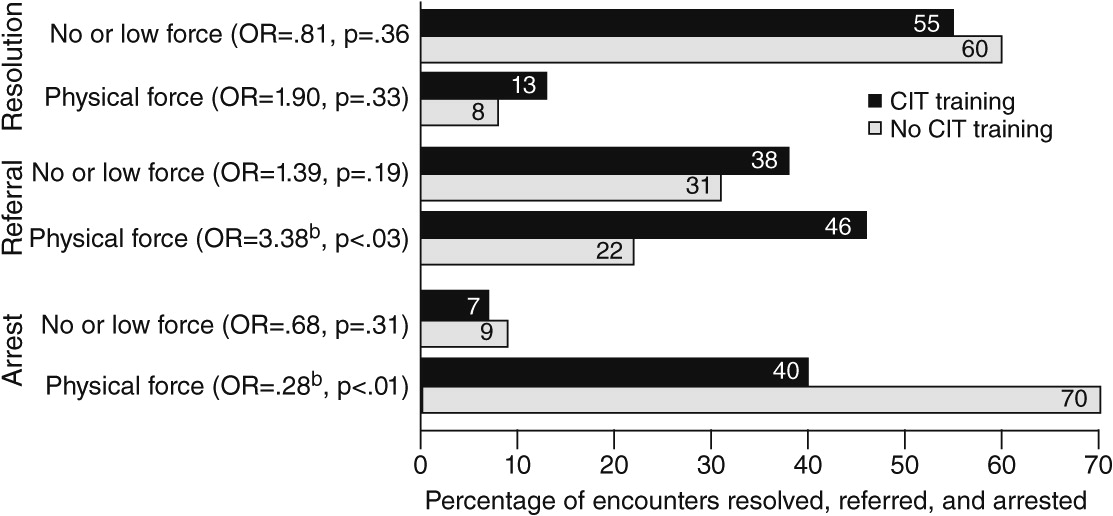

It is interesting that the effects of CIT on referral and arrest were strong and statistically significant when physical force was required and weak and not statistically significant when physical force was not used. Thus, when CIT-trained officers must revert to using force (which, as noted above, is driven primarily by violence potential of the encounter and the subject’s level of resistance), they are nonetheless more likely than officers without CIT training to refer the subject to services and less likely to execute an arrest. The likelihood of referral or arrest differed little between the two groups in encounters in which force was not required.

The sample of encounters was divided into four subsamples on the basis of the type of behavioral condition the officer suspected. Although subdividing the sample limited statistical power, the magnitude of several ORs suggested that the effects of CIT training status on dispositional decisions may vary by the officer’s perception of the subject’s primary problem. Encounters involving CIT-trained officers were less likely to result in arrest, especially for subjects who were suspected of having a mental illness only. On the other hand, encounters involving CIT-trained officers were most likely to result in referral or transport to mental health services when subjects were suspected of having a drug or an alcohol problem only.

We acknowledge five methodological limitations. First, because of the limited number of encounters reported by officers in specific agencies, it was not feasible to include the agency as an analytic variable. However, our intent was to study encounters, not departmental differences. Given the state-level coordination of CIT across jurisdictions in Georgia (

23) and the fact that CIT was well established in each agency, we had no hypotheses concerning departmental variables. Second, although 397 officers provided informed consent and received encounter forms, only 180 returned completed forms. We do not know whether the remaining officers later decided not to participate, failed to document any encounters, did not have any pertinent encounters during the six weeks, or recorded data on encounter forms but did not submit them. Officers’ participation may have been associated with factors that created a selection bias; for example, CIT-trained officers may have been more likely to complete encounter forms when they thought they did a particularly good job. However, the encounter form intentionally did not include officers’ CIT status; they were categorized as CIT trained or not CIT trained using data from the prior survey (

12).

Third, officers without CIT training documented 191 encounters in which they suspected that the subject had a serious mental illness; this figure was 231 for officers with CIT training (21% higher). However, in the CIT model, trained officers can be dispatched to calls in which the subject is believed to have a mental illness. Therefore, one might expect that compared with officers with no CIT training, CIT-trained officers would have reported many more encounters with individuals with mental illnesses. However, dispatch is often unaware that a mental illness is a factor in a call; officers commonly determine that a subject has a mental illness only when they arrive on the scene. Fourth, because officers could have been selective in completing encounter forms, we cannot assume that the arrest and referral rates observed in this large sample of encounters are equal to the arrest and referral rates for all encounters. These encounters were a sample; other methods would be required to determine arrest and referral rates for all encounters, which could then be compared with those of other jurisdictions. Finally, interpretation of most research on CIT is complicated by the fact that officers who undertake the training may differ in personal attributes (for example, a personal or family history of mental health treatment) from those who do not, which might confound differences between groups. Officers typically volunteer for CIT training, and are likely to be motivated to engage more productively with people with behavioral disorders. Additional research should address potential subject-level outcomes while attempting to control for such factors.