Pervasive substance abuse among persons who are homeless significantly impairs efforts to improve the health, housing stability, and social status of this group. The occurrence of alcohol and drug use disorders among persons with a history of chronic homelessness has been reported to be as high as 78% (

1), and substance use can be a primary barrier to transitioning from homelessness to stable housing (

2). Moreover, homeless persons who misuse substances experience elevated risks of mortality (

3), general medical and mental health problems (

4), and criminal justice involvement (

5). These risk factors incur enormous social and economic costs to systems attempting to improve the health and safety of this group (

6,

7). Therefore, identifying supportive housing strategies, wherein homeless persons with substance use problems receive stable housing and access to appropriate clinical and social services, is a high national priority (

8).

The predominant approach to providing supportive housing for homeless persons with substance use problems is the continuum-of-care model, in which housing is contingent upon ongoing compliance with addiction and mental health treatment services (

9). In this model, achieving and maintaining sobriety are required for housing placement and retention. In contrast, Housing First, a more recent supportive housing model, emphasizes a client-centered approach to services and immediate housing placement without requirements for sobriety or treatment participation (

10).

Over the past decade the Housing First model has provoked both advocacy and criticism in the media and scientific literature (

11–

14). Some critics caution against widespread adoption of Housing First, citing a lack of controlled research and concern that providing housing to individuals with chronic substance use problems might lead to worsening addiction, property damage, and harm to other housing clients (

12). Conversely, the model’s proponents argue that multiple empirical studies have reported encouraging results for Housing First providers that target psychiatric as well as substance use disorders—results that include high housing retention rates (

15–

17), significant cost savings (

6), and stabilized or improved substance use (

18–

21).

Virtually absent from the body of evidence about the Housing First model is how consumers respond to variation in the implementation of Housing First practices. Housing First sites nationwide are thought to vary considerably in the Housing First practices they feature and how faithfully the practices are delivered (

22,

23). Differences between organizations in the implementation of a given intervention or model can have a significant influence on client outcomes (

24,

25). Recent studies have offered promising new methods for assessing Housing First implementation, but so far there has been limited examination of the relationship between implementation and outcomes (

26–

33).

In November 2005, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Governor George Pataki signed NY/NY III, committing to create 9,000 units of supportive housing for a variety of disabled homeless people in New York City over ten years. The agreement funded housing for nine target populations, one of which, referred to as population E, is defined as chronically homeless individuals for whom substance use is a primary barrier to independent living. Population E housing was designed to follow a Housing First approach. The adherence of housing providers to Housing First principles was measured by using a fidelity scale derived from qualitative interviews with policymakers and experts who were central to the framing and enactment of population E housing.

This study analyzed the association between differences in program implementation and retention in supportive housing and client substance use during the 12-month period after receipt of housing. We hypothesized that clients housed in programs with high fidelity to Housing First principles related to consumer participation would experience longer housing retention and less substance use at follow-up compared with clients housed in low-fidelity programs.

Methods

Program description

Nine housing providers were awarded NY/NY III funding to provide over 500 units of scatter-site (dispersed in apartment buildings throughout the area) supportive housing to chronically homeless individuals whose substance use is a primary barrier to independent housing.

Table 1 presents key provider characteristics. Providers were expected to follow a Housing First approach for providing client-centered supportive services. All providers were given the same programmatic guidelines and opportunity to participate in learning collaboratives wherein they received centralized guidance regarding client substance use and discharge. This housing is considered permanent, and tenants pay no more than 30% of their income toward rent and utilities.

Procedures

Individuals were offered research participation upon housing entry. Initial “baseline” interviews were conducted within 60 days of moving in and were completed between May 2008 and September 2009. Follow-up interviews were conducted on average 11.5 months after baseline interviews and were completed between October 2009 and July 2010. For each interview, participants were provided a $25 gift card to one of four popular chain stores and compensation for travel expenses. Written informed consent was obtained at baseline. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the governing institutional review board at the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University.

Participants

A total of 550 individuals were admitted to population E housing between December 2007 and September 2009; 358 (65%) housed clients agreed to participate in the baseline interview, 11 (2%) refused to be interviewed, 94 (17%) were ineligible for the study because they moved into the housing from other supportive housing programs, and 87 (16%) did not respond to the interview invitation. The interview sample at the nine housing agencies ranged from seven to 62 clients, representing 20% to 90% of the total number of population E at a given provider. Follow-up interviews were completed by 287 participants, representing 80% of those interviewed at baseline. Among the baseline interview participants who did not complete the follow-up interview, nine (3%) had died, 28 (8%) refused to participate, and 34 (9%) had been discharged from housing before being housed for one year.

Measures

Descriptive information.

Demographic variables (age, gender, race-ethnicity, education, employment, legal history, and housing history) were assessed from the baseline interview. General medical and mental health were measured by using the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) (

34).

Substance use.

The Addiction Severity Index was used to measure the frequency of alcohol, marijuana, heroin, and cocaine use in the 30 days prior to a given interview (

35). The alcohol and drug abuse and dependence modules of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview were used to assess symptoms associated with substance use disorders (

36).

Housing retention.

Housing programs reported entry and exit dates for each client. The total number of days spent in housing was calculated by subtracting the exit date from the entrance date for all clients who had left the program by December 2010. Although follow-up interviews were conducted with clients approximately 12 months after moving into supportive housing, this study documented and analyzed clients’ housing status over a two-year period.

Program fidelity measurement.

In order to identify the essential components of population E housing, qualitative semistructured interviews were conducted with eight key stakeholders (the policy makers, public administrators, experts, and advocates involved in the enactment and framing of the NY/NY III agreement). The research team also reviewed the original funding announcement and program planning documents. Through collaborative review of these primary sources, the research team synthesized eight program components deemed essential to providing housing with high fidelity to the Housing First principles defined by our informants; the full measure is presented in

Table 2.

The resulting eight components constitute two distinct fidelity scales: the supportive housing scale and the consumer participation scale. The supportive housing scale assesses housing agency administration and the design and delivery of supportive services (specifically, staff training, quality of supervision, multidomain intramural services, linkage to extramural general medical and mental health services, and specialized capacity to connect clients to benefits programs). The consumer participation scale assesses fidelity to components that differentiate abstinence-based and Housing First approaches (specifically, client-centered services, interventions to minimize harmful consequences of substance use, and open discussion of substance use behaviors).

The components of the fidelity measure are considered to be critical ingredients of high-quality Housing First programs for population E. However, our measure should not be considered a universally applicable measure of Housing First fidelity. The number of informants queried in this study was relatively small compared with studies that develop general tools for the measurement of Housing First fidelity (

30–

32). Also, some key elements of the Housing First model were held constant across all nine providers and could not be included in our fidelity scale. Eligibility and referral were overseen by government agencies, so components related to these functions were not evaluated. Similarly, because the terms of the funding for all nine providers dictated that the units would be scatter site and master-leased to tenants, components related to housing structure and lease design type were not evaluated.

The Housing First fidelity measure was used to assess program implementation at each study site. The research team conducted interviews with program directors and focus groups of program case managers; reviewed internal program documents; administered questionnaires to program staff; and performed site visits and hosted Housing First implementation learning collaboratives. Two raters with strong experience consulting on supportive housing models developed consensus ratings across all eight dimensions of the framework for each provider. Raters were blind to outcome data. Programs that met fidelity standards for more than three items on the supportive housing scale were rated as supportive housing consistent. Programs that met standards for more than one item on the consumer participation scale were rated as consumer participation consistent.

Statistical analysis

Multivariate analyses were used to test whether provider implementation consistency was associated with client outcomes. Time until exit from housing was modeled with Cox proportional hazards analysis while accounting for clustering of observations within housing provider. Clients’ substance use after being housed was analyzed by using separate mixed-effects logistic regression models for alcohol, cannabis, and stimulants or opioids. For the latter analysis, data were available for only follow-up interview participants. Covariates for all fitted models are listed in

Table 3. Variables describing client substance use in the 30 days prior to baseline interview were used as predictors in substance use models only. All statistical analyses were conducted with Stata 11.

Results

Client demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 3 presents data on housed individuals at baseline. Participants were middle aged, mostly male, and mostly from a racial or ethnic minority group. Participants reported low levels of education, poor work history, and high levels of housing instability. A high proportion reported criminal justice histories. Participants’ responses to the SF-12 were standardized to the mean score of the U.S. population. The average physical health score fell within the lowest quartile of the range of the general U.S. population, but the average mental health score was near the mean of the U.S. population. As expected, clients had recent histories of substance use. Two-thirds of the sample had entered substance use disorder treatment in the five years prior to being housed. There were no statistically meaningful differences among housing providers in clients’ demographic, substance use, or clinical characteristics.

Fidelity to Housing First principles

Five of the nine providers were rated as supportive housing consistent (N=242), and four providers were rated as supportive housing inconsistent (N=116) (

Table 2). In general, supportive housing–consistent providers emphasized training and skill building among staff around practices like motivational interviewing (

37,

38) and brokered a comprehensive array of services for clients. Five housing programs were rated as consumer participation consistent (N=268) and four programs were rated as consumer participation inconsistent (N=90). Consumer participation–consistent programs were successful in adopting client-centered approaches to services planning, openly communicating with clients around substance use, and not requiring participation in substance use treatment. Overall, four providers were rated as both supportive housing consistent and consumer participation consistent, whereas three were rated as both supportive housing inconsistent and consumer participation inconsistent. Two providers had mixed subscale ratings.

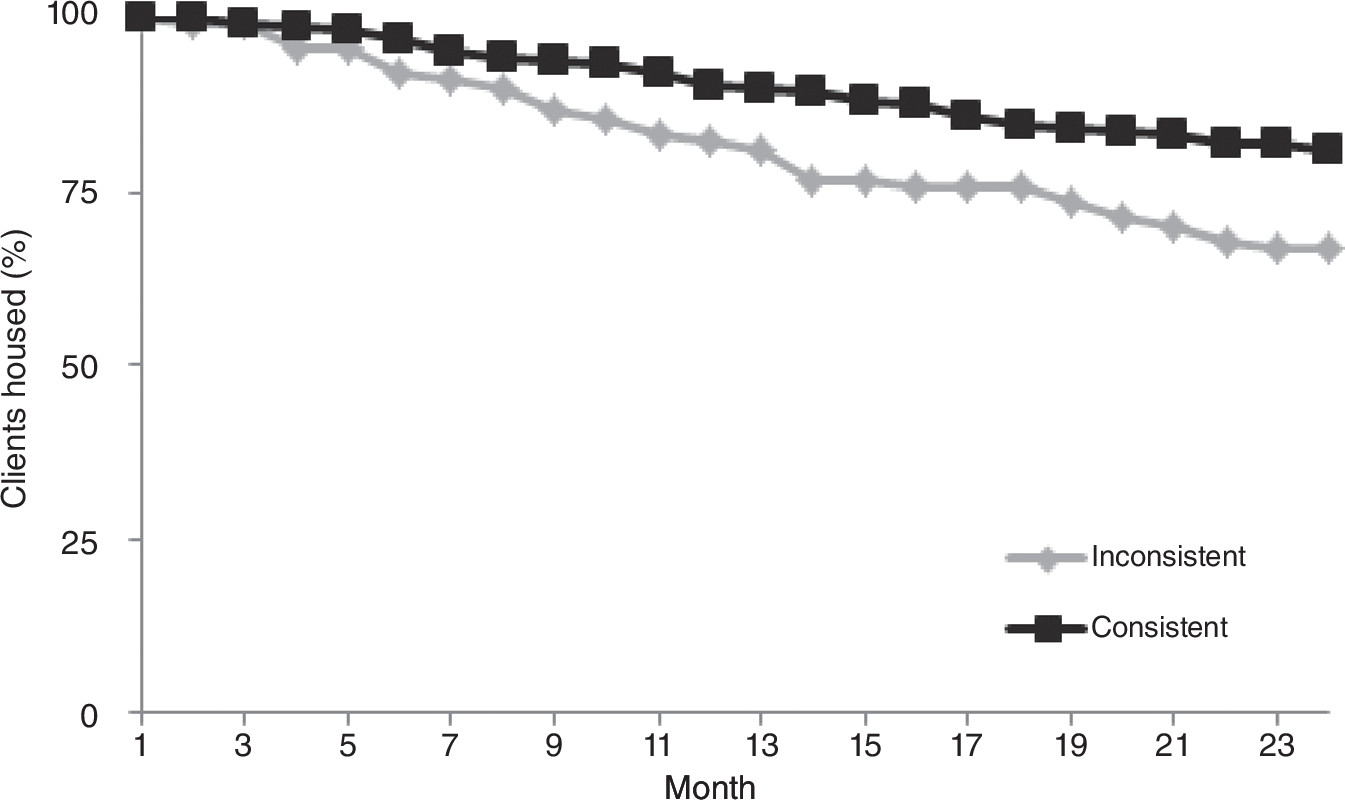

Implementation and retention in housing

As of October 2010, 269 (75%) participants were still housed. The average length of stay was 613±193 days. Among the 89 discharged clients, 18 (20%) left the program voluntarily, 14 (16%) were incarcerated, 13 (14%) were discharged for breaking housing provider policies, and 12 (13%) had died; for 32 (37%), the discharge reason was unknown. Clients in programs that were rated as consumer participation consistent were less likely to be discharged (hazard ratio [HR]=.35, 95% confidence interval [CI]=.14–.87, p=.02) compared with clients in programs that were rated consumer participation inconsistent (

Figure 1 and

Table 4). Consistent implementation of the general supportive housing components had no effect on housing retention (HR=1.37, CI=.59–3.23).

Implementation and client substance use

Alcohol, cannabis, and stimulant or opiate use during the follow-up period was evaluated in separate logistic regression models. There was no association between fidelity in implementation of supportive housing components and client substance use (

Table 4). On the other hand, clients in consumer participation–consistent programs were less likely than others to report using stimulants or opiates at follow-up (odds ratio=.17, CI=.07–.57, p=.002) (

Table 4).

Discussion

The primary aim of the study was to investigate whether variation in the implementation of a supportive housing program modeled on Housing First affected housing stability and client substance use at 12 months. Implementation fidelity was assessed by using a roster of practices defined as core elements of Housing First by policy makers and experts involved in developing the framework for the population E supportive housing program. The elements were organized into two subscales, one related to program administration and the design and delivery of services and the other measuring the degree to which programs offered consumer education about harm reduction practices and allowed clients choice in the services they received. Change in tenant substance use behaviors was measured by conducting client interviews at housing entry and 12 months later.

As expected, compared with clients in programs rated as consumer participation inconsistent, those in programs judged to have consistently implemented consumer participation components were significantly more likely to be retained in housing. This finding provides support for the argument that Housing First programs with client-centered practices foster housing retention of a traditionally difficult-to-house population and is in line with other research linking Housing First with superior housing retention rates compared with abstinence-based programs (

16,

21,

39).

Compared with clients in programs with low fidelity to consumer participation components, those in consumer participation–consistent programs were also significantly less likely to report using stimulants or opiates at follow-up. More research is needed to determine why fidelity to consumer participation components had no effect on alcohol or marijuana use. This finding should be viewed in the context of Housing First practice, which utilizes principles that engage clients in creating their own goals regarding sobriety and harm reduction. It may be that factors such as social stigma or health risks associated with the use of stimulants and opioids led clients to formulate and adhere more readily to goals surrounding these substances. These findings add to the literature reporting that allowing tenants to drink or use drugs on the premises does not necessarily lead to high-risk substance use (

18–

21).

Contrary to expectations, the supportive housing scale was not associated with retention or substance use outcomes. The lack of association may be related to imprecision of the measure or due to the particular characteristics of this population of persons who use substances. There may be predictive or construct validity problems with the supportive housing scale. For example, general components of supportive housing may have a greater influence on retention and substance use–related outcomes than on health and employment outcomes. It is also possible that the scale does not fully capture the essential elements of supportive housing.

The fidelity roster used in this study should be understood in the context of measures emerging in the Housing First field. Researchers at Pathways to Housing (

31,

32) and Watson and colleagues (

30) have each created fidelity scales for evaluation of implementation of the Housing First model. The fidelity scale used in this study has about two-thirds fewer items than the other extant scales. All items on our scale except “Program directors and supervisors provide quality supervision” can be matched to items on the other scales.

Items from other fidelity scales that do not appear on our scale fall into one of two categories. First, several items on other scales pertain to the structure of population E housing and cannot be evaluated at the provider level. Examples of components in this category are flexible admissions policy, population served, housing affordability, scatter-site housing, permanent housing, tenants as leaseholders, and speed of housing placement. Second, items that are not part of our scale but could be measured at the program level include case manager caseloads, regularity of case manager client meetings, unit-holding due to hospitalization or incarceration, and a formal policy to prevent eviction.

This study had several limitations. First, participants were not randomly assigned to programs. However, there were no demographic or substance use differences at baseline between clients across programs. Furthermore, the sample size for the nested statistical models applied in this study limited our ability to declare statistical significance for all but the most robust associations between program type and client-level outcomes.

The fact that we did not drug-test clients was a limitation. Self-report of substance use can be particularly prone to reporting bias (

40–

42). However, it is possible that reporting bias was higher among clients in programs that did not effectively implement consumer participation components, given that those clients may be more concerned about negative repercussions related to disclosure, such as eviction or mandatory substance abuse treatment.

The study was conducted in scatter-site programs located in New York City. Consequently, the results may not generalize beyond users of urban-based scatter-site Housing First programs who have a range of substance use problems and a history of chronic homelessness. Last, it is both a strength and a limitation that the study population did not include people with a serious mental illness. Much of the existing research examines the use of Housing First programs for a population with serious mental illness, and this study extends the evidence base for use of Housing First for those without serious mental illness (

9).

Conclusions

Although Housing First has been associated with encouraging outcomes, variations in the implementation require stakeholders, practitioners, and researchers to better understand the relation between program implementation and key outcomes. Clearly delineated Housing First models and fidelity scales that fit a range of contexts are needed to guide those looking to achieve desirable outcomes similar to those reported in the literature following adoption of a Housing First program. This study lends support to the hypothesis that the consumer participation principles unique to Housing First are associated with positive housing and substance use outcomes among substance dependent, chronically homeless individuals. The key principles examined here included client-centered approaches to goal setting and active communication about substance use and its consequences. Supportive housing providers that demonstrated greater fidelity to these principles retained clients for longer duration and had good substance-related outcomes.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

All study activities and manuscript preparation were supported by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation (grant 2080174). Benjamin Goodman and Jeremy Sorgen contributed substantial assistance to tenant and case manager data collection. Jaqueline Anderson, Rachel Fuller, and Ryan Moser contributed substantial assistance to the implementation evaluation.

The authors report no competing interests.