One goal of the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health was to improve access to mental health treatment for all groups (

1). To do so, it is necessary to identify groups that do not use services despite being ill. Children and adolescents with a psychiatric disorder often do not receive treatment (

2–

6) or receive inadequate care (

6,

7). This level of unmet mental health service need among children, while worrisome, could rise further during the transition to adulthood, a developmental period during which vulnerability for substance use disorders, panic disorder, and other mental disorders is high (

8–

10) and access to mental health services typically declines.

For example, many young adults lose access to services provided through school (typically a primary portal into mental health services), and many cease to be eligible for health insurance under their parents’ policies (although this may change with recent legislation). Young adults are also less likely than any other age group to have private insurance (

11), and many lose eligibility for publicly funded mental health services when they turn 18 or 21.

To date, information about mental health treatment services among young adults primarily comes from cross-sectional studies. Analyses combining the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) and National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) samples found that 18- to 24-year-olds had the lowest rates of any mental health service use among all age groups (

12). However, an analysis of the NCS-R data, which included data for persons ages 25–29 and which were collected more recently than the NCS data, found that 18- to 29-year-olds did not have lower rates of treatment than other age groups in any service sector (

13). The NCS-R found that 41.4% of adults ages 18–29 received some treatment for mental health problems in the previous 12 months. By comparison, 45.0% of adolescents (ages 13 to 17) studied in the NCS-Adolescent (NCS-A) received some treatment for mental health problems in the previous 12 months (

14). A study of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) that focused on young adults (ages 19 to 25), however, found that fewer than one in four had sought services in the prior year (

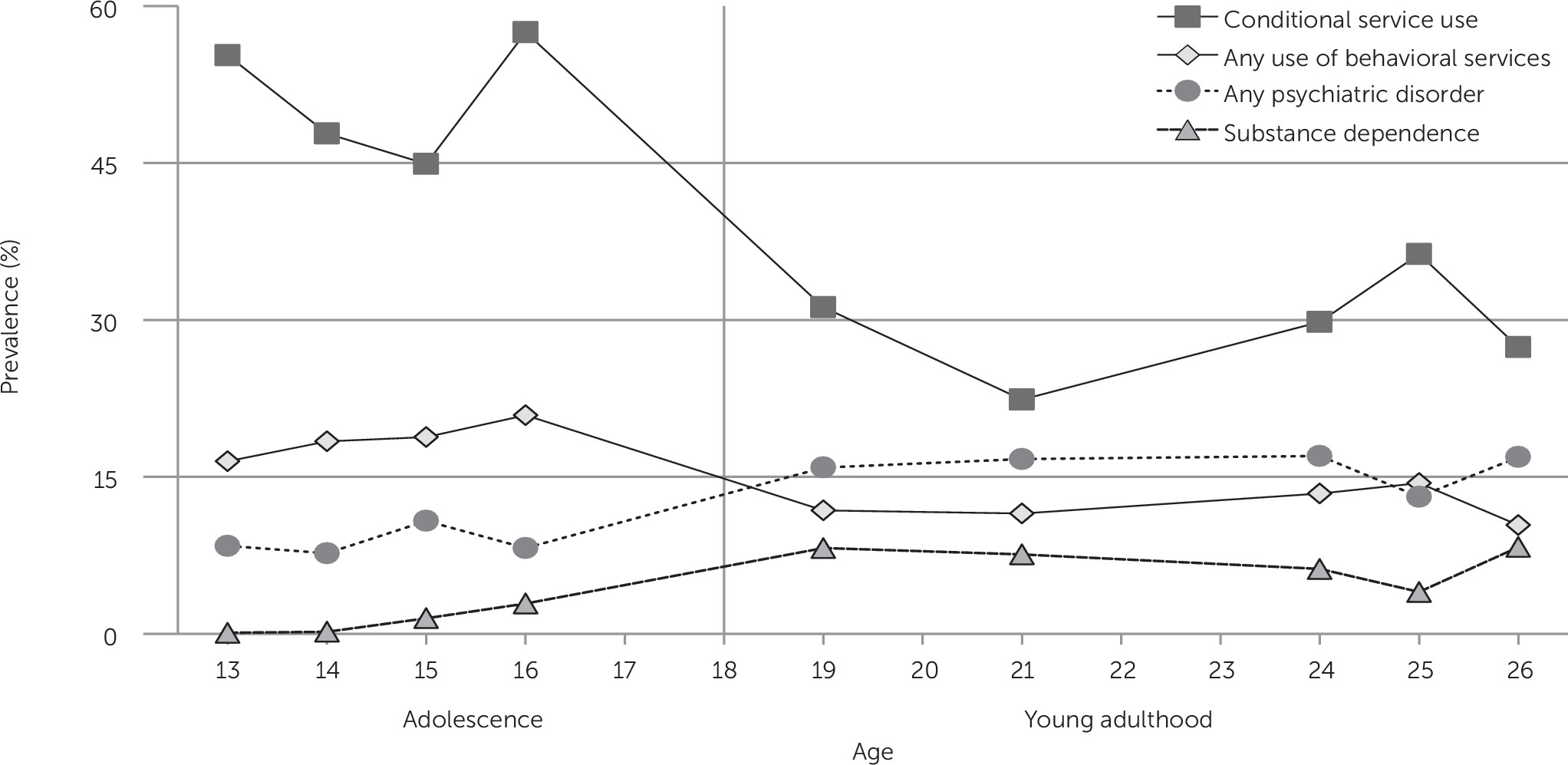

15). Together, these studies imply a significant drop in service use between adolescence and young adulthood that may be erased when youths reach their late twenties. None of these samples followed the same group of children through the transition to clarify whether observed differences were due to factors other than age, for example, cohort or other differences, and to determine the reasons for the differences.

We used data from a longitudinal study of a community-representative sample in the southeastern United States that conducted repeated assessments of children until the age of 26 in order to examine use of mental health treatment during the transition from childhood to adulthood. The prospective-longitudinal design allowed us to look at changes in service use among participants with a psychiatric disorder as well as changes in predictors of service use. This study estimated changes in rates of service use from adolescence to young adulthood among participants with a psychiatric disorder; tested associations between service use and sociodemographic characteristics (for example, sex, race-ethnicity, and poverty), insurance, and psychiatric diagnosis during this transition, and tested whether service use was associated with key developmental tasks of the transition to young adulthood, such as attending college, living independently, marriage, and parenthood.

Discussion

Neuropsychiatric disorders are the leading cause of disease burden among youths ages 10 to 24 (

27). During this period, youths are faced with a series of educational, family, and social transitions. In this sample, the rates of untreated cases of psychiatric disorders increased sharply from adolescence to young adulthood: less than one in three young adults who met criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis reported use of services in any sector. Part of this drop was accounted for by loss of secondary education services, but young adult participants with psychiatric disorders were less likely to use specialty behavioral and informal services. Increased rates of substance dependence coupled with decreased use of services put young adults at high risk of unmet need for psychiatric services.

This sample came from a relatively rural area in the southeastern United States, and, although the sample was representative of that area, blacks and Latinos were underrepresented and American Indians were overrepresented compared with the U.S. population. The racial make-up of the sample raises the question of how informative the sample can be about patterns and predictors of conditional service use. Rates of psychiatric illness in this sample were very similar to those found in other national and international population samples (

28,

29), and the proportion of children receiving needed care for psychiatric disorders was similar to rates in other areas of the United States (

3,

6,

30–

32). Among adolescents, the three-month rate of conditional service use (50.9%) compared closely with the 12-month rate in the NCS-A (45.0%) (

14); among young adults, the three-month rate of conditional service use (28.9%) compared closely to NESARC reports of “fewer than 25% of individuals with a mental disorder in the prior year” (

15). The service use rates in this study were very similar to those from nationally representative cross-sectional surveys. Service use was not assessed with administrative records, because many affected individuals never access any services and not all services for psychiatric disorders are recorded in accessible databases. However, self- and parent-reported service use typically converged with data from institutional records (

22,

33,

34). Finally, a longitudinal design may be susceptible to historical confounds. In this study, this risk was minimized by use of multiple cohorts at intake.

The three-month rate of conditional service use for psychiatric disorders among young adults (28.9%) was much lower than the rate among adolescents (50.9%) and also much lower than the rate reported for young adults by prior cross-sectional studies (

13,

35). Young adulthood seems to be a distinctive period of unmet need compared with adolescence and also later adulthood (41.1% of adult cases of psychiatric disorders in NCS-R [

13]). One obvious reason is that public, tuition-free schooling ends in late adolescence, taking away youths’ primary entry point to the service system for psychiatric disorders (

7). College-based services failed to fill this gap in this study. College students may not always be aware of the services available to them. Surveys of active college students showed that students at private colleges with lower enrollments had higher service use rates (

36), but a majority of young adults is not enrolled in such colleges. Young adults also were less likely than adolescents to access either insurance- and non–insurance-based services. This pattern implicates referral behavior as a reason for unmet service need. Adolescents are typically referred for services by parents (

7), but for many young adults, particularly those living independently, service use is dependent on self-referral. This finding, therefore, raises questions about young adults’ beliefs about service need, stigma, or effectiveness as well as motivation in the face of other distractions and symptoms of their illness. Finally, the rise of substance use disorders during young adulthood may lead youths who misuse substances to believe that their dependence behavior is normative, reducing the perceived need for help. Alternatively, it could be that fewer services are available for substance problems compared with general mental health issues.

Some young adults with psychiatric disorders did receive services. Among young adults, the likelihood of receiving services was not related to either insurance status or poverty, two variables that are often assumed to be barriers to receipt of services. Young adults who received either specialty behavioral or general medical services tended to be white and American Indian youths who lived at home, had a diagnosis of anxiety, or both. Living with one’s parents in young adulthood is on the rise in the United States (

37) and abroad (

38). This trend has been bemoaned in the popular press (

39,

40), where such children have been described as “boomerang kids.” Although aspects of this arrangement may be problematic, our study showed that young adults coping with mental illness experienced advantages from living at home compared with living independently or with a romantic partner or spouse.

Racial-ethnic disparities in use of services are common (

13,

35), but the lower rates of any service use and use of specialty behavioral services in particular among African-American versus white young adults were a sharp departure from the pattern in adolescence. These disparities were not accounted for by poverty, insurance status, or living situation. The period of young adulthood should be a priority of studies of barriers to use of mental health services by African-American youths.