Providing for the complex needs of homeless populations involves a variety of services, yielding high costs for housing programs, psychiatric and substance abuse treatment, and general medical care. Estimated costs of these services may top $50,000 per person annually (

1–

3). Research demonstrates that many individuals move in and out of housing, and some do so repeatedly. Sixty percent of stays in emergency shelters last less than one month, 60% of stays in transitional housing last less than six months, and permanent supportive housing typically lasts less than five years (

4).

For homeless populations, greater service costs may not necessarily reflect better outcomes. One possible reason is that satisfaction with services is not necessarily included as an outcome measure. In a recent study (

6), persons who were homeless perceived benefit from service use if they sensed that it is appropriate to accept social support from others and the service is considered helpful. In this case, receiving a specific service is less about helping meet a particular need and more about improving general satisfaction. An individual’s satisfaction is not typically considered and measured as an effectiveness outcome in research. Consequently, costs of services accrued would not be congruent with effectiveness. In addition, there is no consensus on how attaining housing affects service use costs. In contrast to our research (

7,

8), Larimer and colleagues (

3) found that attaining housing was associated with reduced medical care costs.

Providing services that are not sufficiently matched to the assessed problems of a population may generate costs but not necessarily contribute to improved outcomes. This issue is not about whether outcomes align with costs but about whether the allocation of resources is congruent with assessed needs. Given that needs for treatment of substance use and psychiatric disorders are disproportionately high among persons who are homeless compared with the general population, it is logical to examine whether service costs are congruent with these specific treatment needs.

We developed a series of cost-congruence hypotheses to test assumptions that needs are associated with resources provided for appropriate services in homeless populations. These hypotheses are as follows: attainment of stable housing is associated with lower costs for homeless maintenance and amelioration, attainment of stable housing is associated with higher medical care costs, alcohol and cocaine use disorders are associated with higher costs for substance abuse treatment services, and serious mental illness is associated with higher costs for acute psychiatric and behavioral care.

The purpose of this study was to test the cost-congruence hypotheses in the context of two related issues—whether changes in housing status were associated with changes in costs of specific services used and whether specific service needs were associated with costs. Little is known about how costs for services change with the temporal evolution of housing status in homeless populations. This study empirically tested whether these hypotheses were affected by housing status by using prospective two-year longitudinal data collected from a systematically selected homeless sample in St. Louis, Missouri.

Results

Details about the baseline characteristics of this sample of 255 homeless individuals have been previously reported (

5,

8). To summarize, the sample was predominantly African American (N=192, 75%) and male (N=187, 73%), with a high school education on average (N=149 of 249 participants; 60%). Many had a lifetime history of “legal trouble” (N=158 of 247 participants; 64%), alcohol use disorder (N=151 of 254 participants; 59%), cocaine use disorder (N=113 of 253 participants; 45%), or serious mental illness (N=82, 32%).

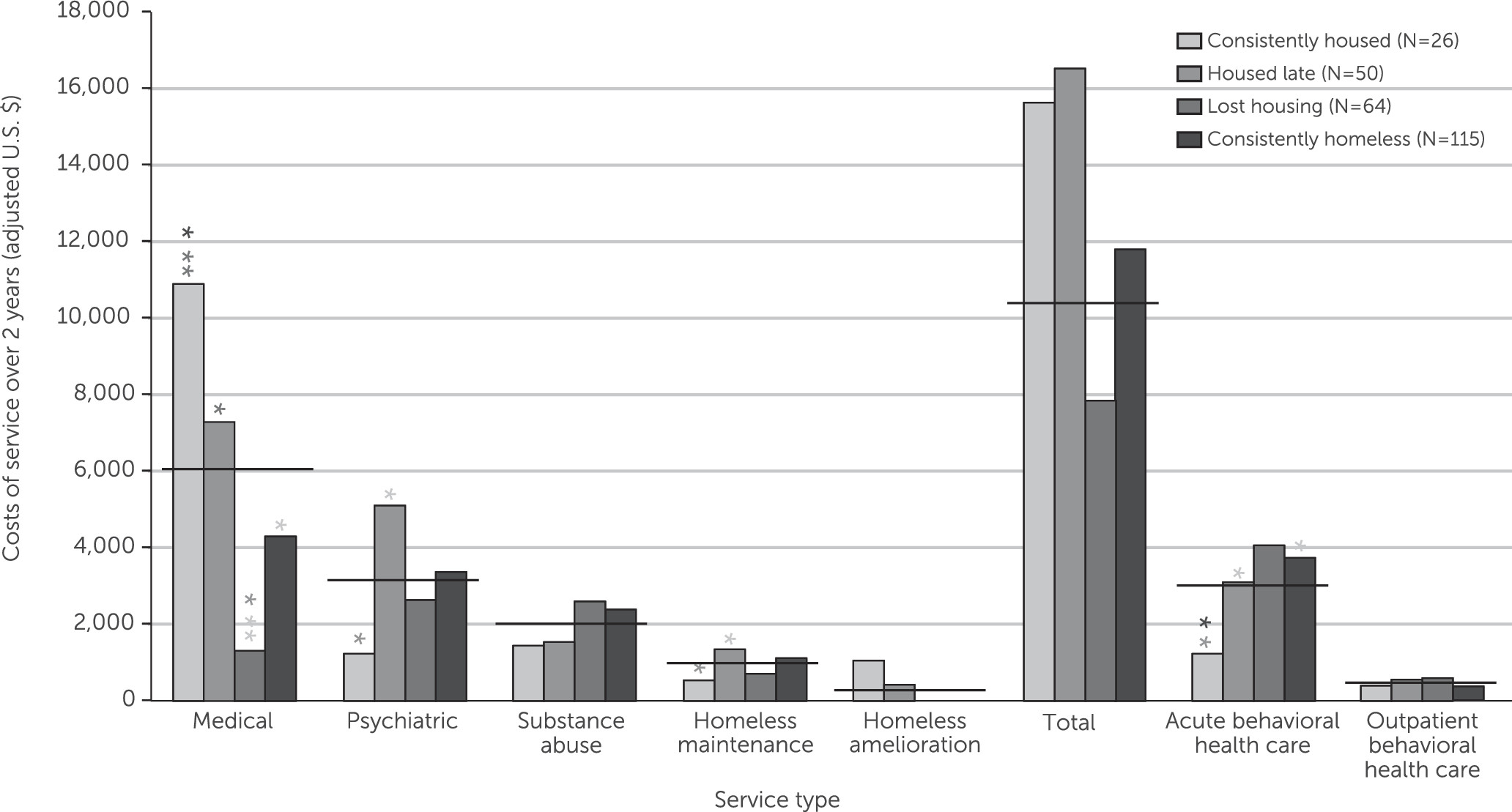

Figure 1 shows costs over the two study years by service use category among the four housing groups. The group that was housed late had the highest total service use costs (mean±SD=$16,545±$17,595), followed closely by the group that was consistently housed ($15,634±$23,279). The medical services category was the most costly overall ($6,029±$13,394). The cost of the next most expensive overall category, psychiatric services ($3,305±$6,973), was significantly lower (Wilcoxon S=75,636, p<.001). Costs of psychiatric services were marginally greater than costs of substance abuse services ($2,004±$4,961; Wilcoxon S=68,238, p=.051).

Compared with mean spending for all other groups, mean costs for medical services were highest for the group that was consistently housed ($10,922±$22,130 versus $4,835±$9,921; Wilcoxon S=7,585, p=.012) and lowest among persons who lost housing ($1,295±$2,007 versus $6,566±$14,020; Wilcoxon S=2,377, p=.008). Among all the groups, psychiatric service costs were lowest for the group that was consistently housed ($1,181±$2,055 versus $3,823±$7,626; Wilcoxon S=5,598, p=.074) and highest among persons who lost housing ($5,090±$8,515 versus $2,707±$6,288; Wilcoxon S=9,515, p=.007). Substance abuse service costs did not vary among the housing groups. Most psychiatric and substance abuse service costs were for acute behavioral care ($3,114±$7,693), and these costs were greater for persons who remained unhoused in one or both years ($3,575±$8,217) compared with those who were consistently housed ($1,224±$4,598; Wilcoxon S=5,133, p=.001). Persons who were housed late had higher homeless maintenance costs than those who were consistently housed.

Figure 1 also shows significant differences in costs in all pairwise comparisons of the four housing groups by each type of service use.

Table 1 summarizes significant results from models testing whether the costs of each service type were predicted by need variables, housing group, and demographic control variables. There was one model for each service type, and the dependent variables were costs. Consistent with the bivariate models, medical and psychiatric service use costs and homeless maintenance costs varied significantly among housing groups, although substance abuse service costs and homeless amelioration services did not. As expected, serious mental illness predicted psychiatric service costs, and alcohol use disorders—but not cocaine use disorders—predicted substance abuse service costs. Serious mental illness also predicted substance abuse, acute behavioral health, and total costs. Women had higher costs relative to men for homeless amelioration ($965±$3,259 versus $2±$20), outpatient behavioral health ($890±$1,634 versus $290±$774), and total services ($15,928±$21,204 versus $12,383±$15,484).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to follow a homeless cohort prospectively and use data from the agencies providing services to calculate cost estimates reflecting resource use per service. Follow-up over a two-year period allowed examination of how obtaining, retaining, and losing housing from year to year affected service use costs during the natural progression of homelessness.

This study found that medical service costs were highest among persons who were consistently housed and lowest among persons who lost housing. One possible explanation is that persons with chronic and severe general medical problems who require costly services may be able to obtain housing through additional resources available for people with disabling general medical conditions. It also may be that persons with housing tend to have greater access to general medical care.

Psychiatric and acute behavioral health service costs showed an opposite relationship with stable housing. Psychiatric service costs were lowest among persons who were consistently housed and highest among persons who were housed late. Similarly, acute behavioral health costs were lower for persons who were consistently housed than for those with any other pattern of housing status. Perhaps services that address psychiatric morbidity do not facilitate the acquisition of housing. Perhaps psychiatric illness, by its nature, does not necessarily lead to service utilization, even when stable housing is obtained. This study examined data on various services directly addressing homeless maintenance. Not unexpectedly, persons who did not obtain stable housing until the second year had higher homeless maintenance costs than those with stable housing in both years.

As discussed further below, the cost-congruence hypotheses predicted that the group that never attains stable housing will have the highest overall service use costs and that the group that attains stable housing will have the lowest overall service use costs. The findings, however, demonstrated a much different pattern, largely attributed to higher medical costs among persons who were consistently housed. This team has previously postulated that obvious acute needs, such as psychiatric illness and literal homelessness, may create barriers to meeting chronic needs (

8).

In contrast, findings of this study supported the cost-congruence hypotheses that costs of medical services, homelessness services, psychiatric and mental health services, and substance abuse services are associated with service needs. Results of multivariate analyses further demonstrated that the costs of services for persons who are homeless are sometimes predicted by factors that are not logically congruent with the persons’ needs. Examples are the associations of housing group with psychiatric services (as noted above), serious mental illness with substance abuse services, alcohol use disorder with outpatient behavioral health services, and serious mental illness with overall costs. In addition, women had greater costs than men for homeless amelioration, total services, and outpatient behavioral health services. Although the cost-congruence hypotheses were generally supported by the findings, understanding the larger cost picture requires application of more nuanced and complex behavioral models to this study’s specific patterns of findings.

Although the findings agree with the services literature documenting the complexity of homelessness, they do not necessarily agree with the conclusion that housing leads to lower societal costs (

3). This difference in findings may in part reflect methodological differences. Prior studies intervened by providing housing and then estimating costs, a method that may not have adequately accounted for the two-way relationship between housing and service use. Further, these intervention studies compared housed groups with groups that remained homeless after the intervention, not accounting for the well-documented phenomenon of movement in and out of homelessness over time—a finding that this team has demonstrated to be significantly associated with overall service use (

5,

7).

Although this study had significant methodological strengths—including a probability sample, longitudinal data collection, and agency-based cost derivation—it also had limitations. The relatively modest analytic sample size (N=255) may have limited power to detect effect sizes. A larger sample might have revealed more subtle interactions among individual needs and appropriate costs. As noted elsewhere (

8), this study’s collection of cost data did not include criminal justice costs—a significant cost driver in other studies (

17). In addition, had follow-up continued for longer than two years, further significant findings would likely have emerged. Perhaps housing needs to be in place for more than one to two years before true cost increases or decreases are fully realized. It may also be the case that cost increases are associated primarily with a small number of high-cost service utilizers. Important information may be gained by focused analysis of high-cost outliers. Further, the cross-sectional sample provided a relative overrepresentation of homelessness chronicity, and thus the findings are especially pertinent to population groups with a history of chronic homelessness. Finally, a proportion of the self-report service use data for each year of the study was collected after collection of the housing-status data.

The findings provided important information to help direct future research. To understand costs over time, studies may need larger samples and examination of costs over longer periods. Studies collecting data over shorter periods may risk inclusion of costs incurred for acute conditions and fail to capture costs associated with periodic acute exacerbations of chronic conditions. This point is of particular relevance for studies examining immediate cost consequences of interventions for specific acute conditions.

Future research is needed to address how societal costs change with housing status, both in the aggregate and across agencies. The findings suggest that aggregate societal costs associated with services for persons who had been homeless may increase after the individuals find housing, and there may be cost shifting among agencies. Future research may indicate that providing services to improve outcomes among people in need does not always save money. However, detailed and accurate estimates of costs are critical to understanding how to distribute scarce service resources.

The findings also suggest the need to consider the potential benefits of including preventive health services as part of the care provided to homeless persons. As we suggested in another publication (

8), medical costs may increase if providers prefer addressing acute needs, ignoring asymptomatic chronic conditions. As indicated in the broader homelessness literature, the relative risk of death among persons who are homeless is considerably higher than in the general population (

18), consistent with this study’s findings of five known deaths over the course of the study (

11). Including medical services as part of routine homelessness care may decrease medical service costs and improve outcomes related to both mortality and morbidity.