Spending on psychotropic medications exerts considerable pressure on mental health budgets. From 1996 to 2001, the increase in real terms was 20% per year (

1), with increases of 4% per year since then (

2). The early increases reflected, in part, new second-generation antipsychotics, which dominated budgets for Medicaid patients and nonelderly Medicare patients (

1). One approach to reducing pharmacy costs is to rely on psychiatrists to prescribe cheaper alternatives. An analysis of different pharmacy cost containment plans concluded that physicians were unaware of prescription costs, which undermined potential savings (

3). Unfortunately, educating physicians through academic detailing has not been shown to decrease costs (

4).

In contrast, mandating use of generic medications is promising. A comparison of states that do and do not require patient consent for medication switches has shown that mandating generic use lowers pharmacy costs (

5), as has a within-state comparison in a state that permits different approaches (

6). However, the potential savings must be balanced against costly adverse outcomes. Two outcomes that could wipe out savings are increases in hospitalizations resulting from medication instability and gaps (

7,

8) and increases in the number of prescriptions per patient (

9).

Our organization mandated use of generics after financial challenges compelled budget scrutiny. In this column, we present some pre-post data suggestive of what could happen after such a policy is implemented.

The policy change

It is important to understand the funding context of the policy change. In Michigan, publicly funded mental health services are coordinated through 46 regional community mental health service programs, one of which covers Wayne County (approximately two million residents). To increase competition, the local program delegated the funding and coordination of psychiatric clinical care to two competing provider networks and placed them at fiscal risk, with payments risk adjusted for services provided. Gateway Community Health (GCH) is one of the nonprofit networks, and in fiscal year 2013 it was responsible for 22,444 active members. Approximately 40% of members are covered only by general funds (for those without behavioral health insurance or who have suboptimal coverage or have exhausted their coverage), but the exact number is fluid because people move in and out of other coverage, such as Medicaid. As the clinical care funder, GCH is responsible for its members’ mental health services (including psychotropic medications for members covered by general funds) and psychotropic and nonpsychotropic prescription medications during psychiatric hospitalizations. During the period of this analysis (2010–2013), the number of general fund members increased by 10%, 3%, 27%, and 16% annually.

To address high costs, GCH’s medical director held several meetings in the summer of 2011 with clinic physicians and directors to educate them about medication costs and the need for evidence-based treatment in the hope that they would prescribe less costly medications. In the face of continued high expenditures, a mandated generic psychotropic medication policy was implemented—a three-month transition period culminated in full implementation in November 2011. Appeals were granted if there had been two or more adequate trials of generics from the same medication class and if coverage had been denied by medical and pharmacy assistance plans. GCH’s medical director was responsible for reviewing appeals and cases in which more than one generic medication from a class was prescribed. To avoid gaps in medication, selected nonpsychotropic medications (for example, antibiotics and medications for diabetes, cardiac and respiratory problems, and seizures) were also covered after discharge from inpatient psychiatric care until the person obtained Medicaid or other coverage. Despite adding to costs, the concern was keeping the member healthy. Because these costs were part of the mental health pharmacy budget, they are included in the analysis.

Analysis of expenditures

We examined monthly pharmacy expenditures for the six months before the policy mandate (preimplementation), the three-month implementation period, the five months postimplementation, and 13 months later. The monthly information, which was gathered for members without pharmacy benefits from other payers, covered total pharmacy expenditures, number of prescriptions, mean cost per prescription, number of members with a prescription, mean number of prescriptions per member with a prescription, and percentage of expenditures on brand-name medications. To assess impact on hospitalization, the number of hospitalizations per month for all members and for members whose hospitalization was not covered by other payers (although their medications may have been) was also summarized. Plots were used to assess trends within these periods before the data were aggregated. All comparisons of pharmacy data across the four periods were significant (p<.001). The study was classified as not human research by the Wayne State University Institutional Review Board.

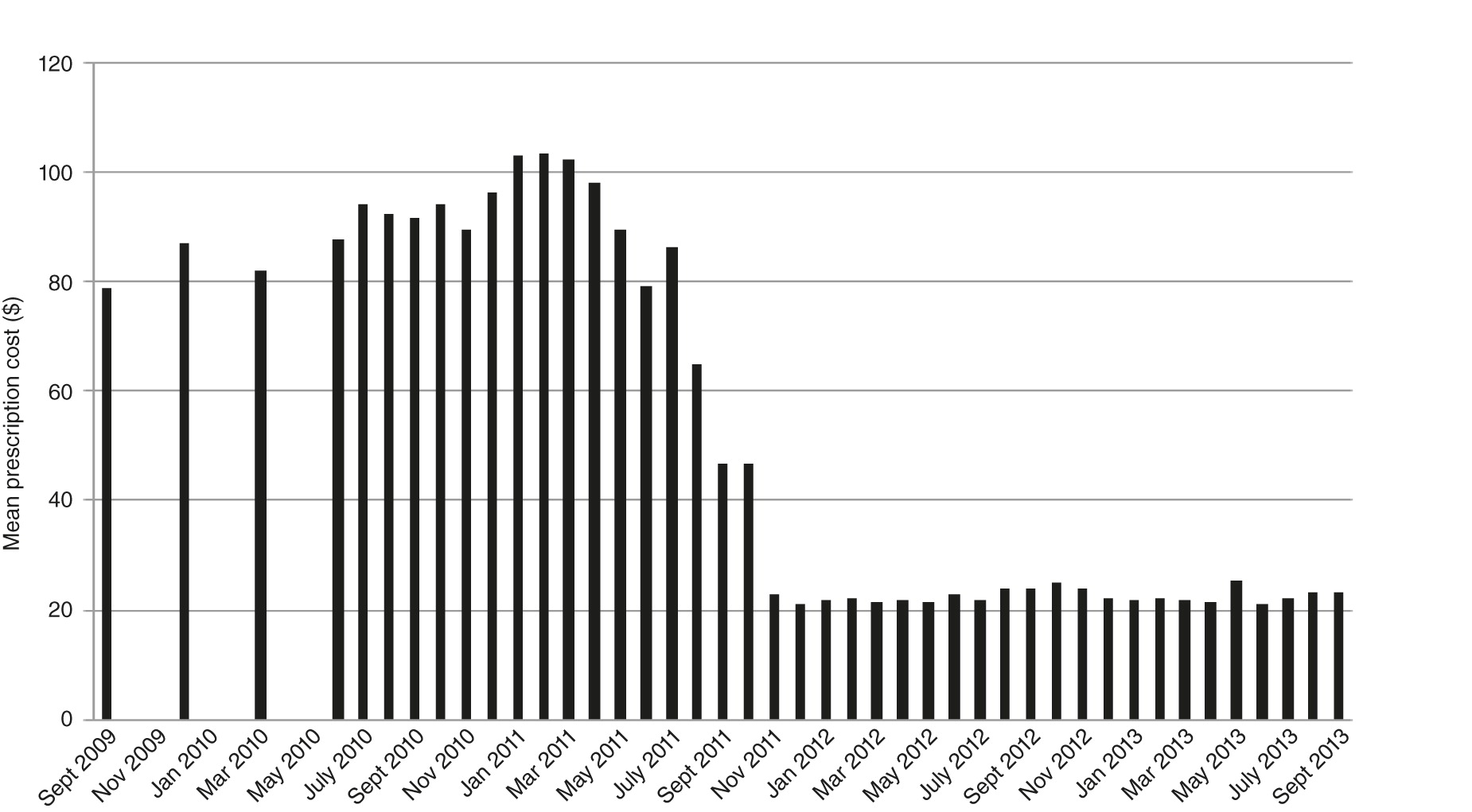

The costs per prescription were consistently high before the policy implementation (

Figure 1). Postimplementation, costs dropped dramatically, as did the proportion of brand-name medications. [A table summarizing cost and other data is available in an online

supplement.] During this period Zyprexa, Geodon, Seroquel, and Lexapro went off patent. The policy was temporally associated with changes in monthly expenditures. Changes were also related to the number of members filling prescriptions.

Adverse outcomes did not increase postimplementation. The mean monthly number of prescriptions per member did not increase. No consistent trend was observed in mean hospital admissions, although during the implementation period a jump was noted in hospitalizations per month among members covered by general funds.

Discussion and conclusions

This was a retrospective analysis of a community-based provider network taking actions in financially challenging times—not a clinical trial—and there are substantial limitations in interpreting the numbers. We looked for changes in agencies, prescribers, barriers to filling prescriptions, and members that might have affected our findings. No new agencies joined the network, and no agency stopped being a member. The monthly number of prescribers varied from a low of 121 in June 2013 (follow-up) to a high of 162 in January 2011 (preimplementation). The percentage of physicians with one prescription filled monthly—about 20%—showed less variability. The median number of prescriptions per physician climbed from two to four. One barrier, closure of a pharmacy at a major clinic, occurred during preimplementation. After a few months, a new pharmacy opened in the same location.

The number of new members is more difficult to measure. The number of new members covered with general funds increased over the period. However, these members may have switched to Medicaid, which has its own pharmacy benefit. In a per capita system, an accurate member count is expected. In a system based on risk-adjusted compensation with members allowed to switch monthly and different funding streams, an accurate count is more difficult. The changes reflect GCH’s financial problems, which meant that new members were steered to the other provider network by the regional community mental health program. When the financial situation improved, partly as a result of the pharmacy policy, new members were again assigned to GCH.

Other limitations include the single-site, pre-post design with no comparison group and the relative rarity of psychiatric hospitalization, which made it difficult to assess changes over time. Also, quality of care was not examined, such as by assessing changes in medication adherence. In addition, the periods examined were not of equal length, resulting in a shorter time to smooth out fluctuations during implementation. An examination of the plots indicated no large fluctuations, except for cost of nonpsychotropic medications, which was dependent on the admission and discharge of patients with general medical illnesses. Another limitation was lack of statistical control for potential seasonal effects. The data show the limitations of evaluating policy implementation in the real world; events beyond one institution’s control, such as the closing of a pharmacy and an increase in newly eligible members, may play pivotal roles.

In conclusion, pharmacy expenditures can overwhelm public mental health budgets. This analysis shows that controlling medication costs for people with serious mental illness in an urban area is feasible through mandated use of generic medications. Feasibility was greatly assisted when brand-name antipsychotics went off patent. The decline in total pharmacy expenditures occurred even as more people filled prescriptions. Mandating generic use did not result in increases in prescriptions per person or in hospitalizations. Limited expansion of nonpsychiatric medication coverage after hospitalization did not result in a large cost increase. It is important to emphasize that prescriptions of brand-name medications were still allowed, but generic alternatives had to be tried first. A rapid appeal process to a practicing psychiatrist was available. In the absence of medical breakthroughs or new support for mental health budgets, mandating generic use is an effective tool to control one portion of the budget.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Study funding was provided by the Lycaki-Young Funds (State of Michigan), Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority, and Gateway Community Health.

The authors report no competing interests.