Alcohol use disorders are common and characterized by a low occurrence of treatment seeking among affected individuals (

1–

6). In the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, only 7.9% of participants with a past-year alcohol use disorder received treatment (

7). Although some individuals successfully recover from an alcohol disorder without formal treatment (

8), treatment has been shown to improve outcomes (

9–

13).

Factors related to treatment utilization for alcohol problems are multifaceted and complex. In this study, we drew on Andersen’s model of health service use, which identifies predisposing characteristics (social and demographic factors and personal health attitudes), enabling factors (financial and structural resources), and need as predictive of service utilization (

14). Predisposing characteristics are the most distal predictors of service use, followed by enabling factors, with need (perceived or real) being most proximal. As we review below, previous alcohol treatment studies have established associations between many of Andersen’s factors and treatment utilization and have found perceived treatment need to be one of the strongest predictors. However, many individuals who perceive a treatment need also perceive barriers to treatment. These perceived barriers are an important impediment to treatment (

4,

7,

15–

18).

Andersen’s predisposing characteristics show the least robust associations with treatment utilization. Several studies have found that unmarried individuals are more likely to receive treatment for substance use disorders (

1,

2). Numerous studies have found that men are more likely to receive treatment (

1,

2,

19–

25), but others have found higher treatment rates among women (

26,

27). Similarly, studies have reported that individuals from racial-ethnic minority groups are more likely (

4,

20,

23,

28), as likely (

1,

21,

29), or less likely to receive treatment (

30,

31) compared with non-Hispanic whites. Finally, studies have reported higher treatment rates among both older (

1,

3,

25) and younger (

20,

23) individuals.

With regard to Andersen’s enabling factors, studies have found that individuals with higher income and education levels were less likely to receive substance use disorder treatment (

1,

2,

19,

20,

28). These individuals may be more likely to have stigmatizing attitudes toward treatment, to consider themselves as having “more to lose,” or to have less severe drinking behaviors and consequences (

1). Individuals who are uninsured also have been found to have lower rates of treatment (

20,

30,

32), likely as a result of decreased access to or increased cost of services.

Treatment need, comprising both actual and perceived need, is identified by Andersen as one of the most proximal determinants of treatment (

14). Yet the overwhelming majority of individuals with an alcohol use disorder (approximately 90%−95%) do not perceive a need for treatment (

4,

7,

33). This hallmark of alcohol disorders may be the most pervasive impediment to treatment (

18,

33). For individuals with a perceived treatment need, perceived need has been shown to be one of the strongest predictors of treatment utilization (

4,

5,

32,

34,

35). Factors associated with perceived need include age, marital status, family history of alcohol problems, severity of alcohol problems, and comorbid psychiatric problems (

5,

17,

33,

35). Disorder severity is another component of need: individuals are more likely to receive treatment if they experience alcohol dependence compared with abuse (

1–

3,

36) or if they experience greater consequences of drinking (

23,

28,

37). Comorbid psychiatric conditions are also strongly associated with treatment utilization (

1,

3,

5,

17,

19,

20); it is possible that comorbidity increases treatment need or that individuals who are receiving psychiatric treatment are more likely to be referred for alcohol treatment.

Even though perceived need is a strong proximal factor for treatment utilization, only 15%−30% of individuals with perceived treatment need receive treatment (

1,

2,

7,

34). Perceived barriers to treatment help explain this treatment gap, given that those who do not seek treatment typically report more barriers than treatment seekers (

15,

16). Attitudinal barriers, such as the belief that one should be “strong enough” to handle alcohol problems on one’s own, have consistently been found to be the most prevalent barriers (

4,

15–

17,

34). Previous studies have primarily examined prevalence and correlates of barriers. Little work has examined heterogeneity among individuals with respect to perceived barriers. It is likely that individuals who do not seek treatment can be categorized into subgroups characterized by distinct sets of perceived barriers.

In this study, we used latent class analysis (LCA) to examine data from a large, population-based survey of U.S. adults to identify subgroups of individuals with a lifetime alcohol use disorder and a perceived treatment need who do not seek treatment. In addition, we examined the associations between subgroup membership and factors previously shown to be associated with perceived need and treatment seeking. This study is one of the first to examine heterogeneity in barriers among treatment-naive individuals with a recognized treatment need. Identifying subgroups among those who do not seek treatment can inform screening and treatment outreach efforts and represents an important step toward increasing alcohol treatment.

Methods

Sample

Data are from wave 1 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (

38,

39). Face-to-face interviews assessed present and past alcohol consumption, utilization of alcohol treatment services, and an extensive diagnostic battery of substance use and psychiatric disorders. Wave 1 of the NESARC (N=43,093) was conducted in 2001–2002.

In total, 11,843 (27%) of wave 1 NESARC participants met DSM-IV criteria for a lifetime alcohol use disorder (lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence or both), the majority of whom had never received treatment (N=10,004). Of these treatment-naive individuals, only 10.5% (N=1,053) perceived a need for treatment as assessed by the following question: “Was there ever a time when you thought you should see a doctor, counselor, or other health professional or seek any other help for your drinking, but you didn’t go?” Questions regarding specific treatment barriers were asked only when individuals reported a perceived treatment need; thus our study sample consisted of the 1,053 treatment-naive individuals with a lifetime alcohol use disorder and a perceived treatment need. [A figure illustrating sample selection is available in an online supplement to this article.]

Assessment

Individuals who reported a perceived need were asked to identify reasons for not seeking treatment from a list of 26 barriers. In this analysis, a subset of 15 items was used because of infrequency of responses and content overlap of the remaining items.

Alcohol abuse and dependence, nonalcohol substance use disorders, and psychiatric conditions were assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (

40) on the basis of

DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. Individuals were classified as having a lifetime history of abuse only or of dependence with or without abuse. Mood disorders included in the analyses were major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder. Anxiety disorders included generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, and agoraphobia. Substance use disorders included abuse of or dependence on marijuana, stimulants, sedatives, tranquilizers, cocaine, heroin, opioids, inhalants, hallucinogens, and other drugs. Individuals were classified as having a lifetime history of a mood, anxiety, or nonalcohol substance use disorder if they met lifetime criteria for at least one mood, anxiety, or nonalcohol substance use disorder, respectively.

Other variables included in the analyses were sex, age (18–29, 30–49, and ≥50), race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other), education (less than high school, high school, and greater than high school), household income (<$15,000, $15,000–$29,999, $30,000–$59,999, and ≥$60,000), insurance status (none, public, and private), whether the individual lived with a partner, and parental history of alcohol problems.

Statistical Analysis

LCA empirically identifies the structure of an underlying categorical latent variable based on observed patterns in latent class indicators (

41). Using 15 NESARC items addressing specific barriers to treatment, we conducted LCA to identify subgroups of individuals with similar barrier patterns. To determine the optimal number of latent classes, we implemented LCA models with one to five classes and considered the following fit statistics: Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), adjusted BIC, Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR LRT), and entropy (

42–

46). Lower values of AIC, BIC, and adjusted BIC indicate better fit, yet these statistics often marginally decrease with each additional class. To avoid overfitting the LCA model, we selected the class size associated with the last substantial decrease (

47,

48). As a sensitivity analysis, we also fit LCA models with all 26 items; the resulting class structures were highly similar; therefore, for parsimony we present the results from the 15-item LCA.

Latent class regression (LCR) was implemented to estimate the associations between covariates and latent class membership. Covariates that had previously been shown to be associated with perceived treatment need or treatment utilization were selected for inclusion in the LCR. Univariate (unadjusted) regressions were considered first, and all variables significant at the .20 level were included in the final multivariate (adjusted) LCR model. LCA and LCR were performed in Mplus version 7.11, which uses maximum likelihood estimation to obtain estimates of model parameters (

49). All analyses accounted for NESARC survey weights, clustering, and stratification.

Results

Sample Characteristics

In our sample of 1,053 treatment-naive adults with a lifetime alcohol disorder and a perceived treatment need, the mean±SD age was 43.8±13.4 years; 68% were male; 76% were non-Hispanic white, 9% were Hispanic, 8% were non-Hispanic black, and 7% were from other racial-ethnic groups (

Table 1). Eighty-three percent met lifetime criteria for alcohol dependence, and the remaining 17% met criteria for alcohol abuse. A parental history of alcohol problems was common: 52% reported paternal drinking problems, and 20% reported maternal drinking problems. Lifetime psychiatric disorders were prevalent: mood disorder, 56%; anxiety disorder, 40%; and nonalcohol substance use disorder, 52%.

Consistent with previous studies (

4,

15–

17,

34), individuals primarily reported attitudinal barriers to treatment (

Table 1). Most frequently reported was the belief that “I should be strong enough to handle [it] alone” (42%), followed by the belief that “the problem would get better by itself” (33%). In addition, 21% reported that their drinking problem “was not serious enough” to seek treatment. The most common stigma-related barrier was that an individual was “too embarrassed to discuss it with anyone” (19%). The most common financial barrier was that the individual “couldn’t afford to pay the bill” (14%). Structural barriers (“didn’t know any place to go for help,” “didn’t have any way to get there,” and “didn’t have time”) were the least frequently reported; each was endorsed by less than 10% of participants.

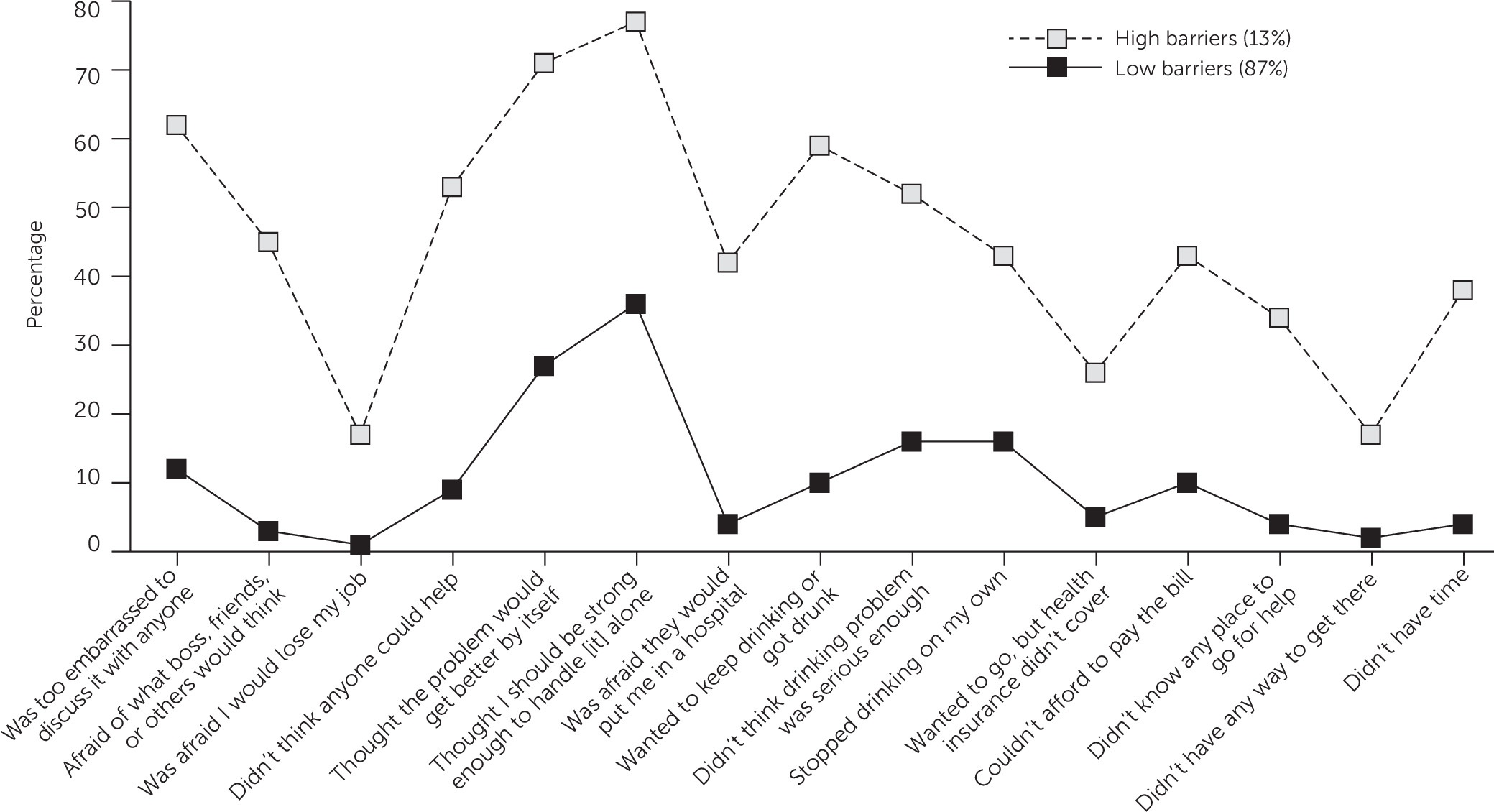

LCA Results

A two-class model was determined to be optimal on the basis of the information criteria statistics (AIC, BIC, and adjusted BIC) and the LMR LRT test (

Table 2). This model had an estimated entropy of .89, indicating good class differentiation (

44). We characterized the two classes as the high-barriers class and the low-barriers class, with a majority of individuals (87%) belonging to the low-barriers class. Individuals in the low-barriers class were moderately likely to endorse several attitudinal barriers and relatively less likely to endorse other items for all of the remaining items (

Figure 1). The most commonly endorsed item for the low-barriers class was “I thought I should be strong enough to handle [it] alone” (36%), followed by “the problem will get better by itself” (27%), and “I stopped drinking on my own” (16%).

In contrast, 13% of individuals were estimated to belong to the high-barriers class, characterized by a moderate to high probability of endorsement across all items. Indeed, for every individual item, the probability of endorsement was higher for the high-barriers class than for the low-barriers class. As in the low-barriers class, the most commonly endorsed items were “I should be should be strong enough to handle [it] on my own” (77%) and “the problem will get better by itself” (71%). However, the high-barriers class also reported stigma, lack of readiness for change, and financial and structural barriers. For example, 62% of individuals in the high-barriers class were “too embarrassed to discuss it with anyone,” compared with 12% in the low-barriers class; 59% “wanted to keep drinking or got drunk,” compared with 10% in the low-barriers class; 45% were “afraid of what boss, friends, family, or others would think,” compared with 3% in the low-barriers class; and 43% “couldn’t afford to pay the bill,” compared with 10% in the low-barriers class. In summary, the classes were similar in that the most common barrier for both classes was attitudinal; yet the high-barriers class faced notably more barriers across multiple domains.

LCR Results

LCR was conducted to estimate the unadjusted and adjusted associations between class membership and personal characteristics, including demographic characteristics, alcohol disorder severity, family history of alcohol problems, and comorbid conditions. We present the estimated odds ratios (ORs) for being in the high-barriers class relative to the low-barriers class for each covariate (

Table 3). In the univariate analyses, all variables except race-ethnicity, insurance status, and partner status were associated with class membership at the p<.20 level; these three variables were not included in the multivariate analysis. Alcohol dependence, compared with alcohol abuse, was significantly associated with the high-barriers class (OR=2.63, p=.02). A maternal history of alcohol problems was also predictive of being in the high-barriers class (OR=1.91, p=.02), and a paternal history was associated at the trend level (OR=1.61, p=.08). A lifetime mood disorder, anxiety disorder, and nonalcohol substance use disorder were each significantly associated with the high-barriers class (OR=2.36, OR=2.81, and OR=2.07, respectively; all p<.05).

In the adjusted model, a lifetime anxiety disorder was significantly associated with the high-barriers class (AOR=1.93, p=.03). The association with maternal history of alcohol problems was attenuated and significant at the trend level (AOR=1.79, p=.06), but the association with alcohol dependence was no longer significant (greater than high school compared with less than high school, AOR=1.52, p=.40). A higher education level was significantly associated with the high-barriers class (AOR=2.70 p=.03). Finally, lower income was associated with the high-barriers class at the trend level (<$15,000 compared with ≥$60,000, AOR=2.07, p=.08).

Discussion

We conducted a novel analysis that identified heterogeneous subgroups with respect to perceived alcohol treatment barriers among treatment-naive adults with a lifetime alcohol disorder and a perceived treatment need. In this population-based sample, individuals were best characterized as belonging to one of two distinct groups, characterized as the low-barriers class and the high-barriers class. The vast majority of individuals (87%) were in the low-barriers class and endorsed primarily attitudinal barriers to alcohol treatment. Individuals in the high-barriers class (13%) represented a small but important subgroup that endorsed a complex set of attitudinal, readiness-to-change, structural, financial, and stigma barriers.

Attitudinal barriers were the most commonly reported barriers across both classes, consistent with previous studies (

4,

15–

17,

34). Furthermore, for a majority of individuals, the only perceived barriers were attitudinal. Given that attitudinal barriers may be the most modifiable, our findings suggest that interventions to reduce the stigma of alcohol treatment and to increase motivation for behavior change may be effective and sufficient for the majority of individuals with perceived treatment barriers. To this end, we endorse the use of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) in primary care (

50). SBIRT’s screening component may be particularly beneficial for individuals with no perceived treatment need, who constitute the majority of individuals with alcohol problems. The brief intervention component could include motivational interviewing (

51), which may be beneficial to individuals with attitudinal barriers. Routine screening may encourage discussion with health care providers. Similar screening campaigns for depression have been successful at increasing awareness, reducing stigma, and increasing treatment uptake (

29). Although physicians are increasingly implementing such evidence-based practices, many still report feeling uncomfortable asking patients about alcohol and other substance use. Medical education should seek to improve clinician self-efficacy in discussing alcohol and other substance use problems with patients. Furthermore, we believe that alcohol screening could be augmented to include several screening items regarding treatment barriers. This would help clinicians identify whether individuals primarily face attitudinal barriers or a more complex set of barriers, which could aid in decisions regarding treatment and supportive services.

Our results also highlight independent associations of several factors with the high-barriers class: alcohol dependence, family history of alcohol problems, and comorbid psychiatric disorders. These factors have previously been found to be associated with treatment seeking and perceived barriers (

1,

3,

5,

19,

20,

33,

36). The observed attenuations in the adjusted model may be due to the co-occurrence of these factors. For example, 88% of those with a maternal history of alcohol problems and 86% of those with a paternal history met criteria for alcohol dependence rather than abuse. Overall, we found that lifetime psychiatric disorders, particularly anxiety, were associated with belonging to the high-barriers class. Increasing integration of substance use and mental health services may promote treatment uptake by this population.

This analysis is a cross-sectional description of class membership. Membership may change over the course of an individual’s alcohol use disorder because of shifts in readiness for change, attitudes, or life circumstances. These classes may reflect individuals at different stages of change as described by the transtheoretical model of change (

52): individuals who are farther from the action stage may belong to the high-barriers class and may transition to the low-barriers class as they near the action stage. Alternatively, changes in employment, financial circumstances, or relationship status may affect barriers and result in shifts between classes.

Several limitations deserve mention. First, this analysis was not designed to identify causal associations. Because of the cross-sectional nature of the data, we cannot establish temporal ordering of covariates and class membership. For example, we were not able to establish whether psychiatric disorders were present during the period of perceived treatment need. Second, social and temporal trends regarding stigma and treatment accessibility over the past decade may somewhat limit the generalizability of our findings. Although national surveys indicate that rates of alcohol treatment seeking have remained essentially flat since the NESARC data were collected (2001–2002) (

7), data are lacking regarding temporal trends in perceived barriers. Third, although the use of LCA accounted for measurement error with regard to barriers to treatment (

41,

53), our analysis may still be subject to misclassification bias. Furthermore, all NESARC data were self-reported and thus may be subject to recall bias or social desirability bias. Finally, NESARC data were limited to barriers from the participants’ perspectives and did not include information regarding barriers at the provider, state, or national level.

Conclusions

This study identified two distinct subgroups among treatment-naive adults with a lifetime alcohol use disorder and a perceived treatment need. Our results highlight that the majority of individuals face few, and primarily attitudinal, barriers and that a notable subset faces a complex set of barriers. Routine screening may help identify individuals with an alcohol use disorder who do not seek treatment. Individuals in the low-barriers class may benefit from motivational interviewing, and those in the high-barriers class may require more innovative and comprehensive treatment strategies.