Over the last three decades, homelessness has emerged as a significant social problem in Canada and the United States (

1–

4). The prevalence of chronic general medical problems, mental illness, and addictions and the associated acute care costs are significantly higher among homeless populations compared with the general population (

5–

7).

The predominant program model for reducing homelessness among persons with severe and persistent mental illness and other medical conditions can be characterized as a continuum of services in which individuals progress through shelters, transitional housing, and, eventually, permanent housing. The aim of this approach, often referred to as “treatment first,” is based on the assumption that individuals must be stabilized before being housed. Research indicates that treatment-first programs can be effective in reducing homelessness among clients who follow the programs’ treatment regimens (

8,

9). However, this approach has shown limited success among clients who encounter obstacles to treatment adherence. Such individuals tend to remain homeless and have extensive contact with emergency rooms, detox centers, criminal justice institutions, or other acute care systems, or they may stay disengaged from services (

6).

Pathways to Housing, an organization located in New York City, developed an alternative program for this population called “Housing First” (

10). Founded on the principles of psychiatric rehabilitation and consumer choice, Housing First offers immediate access to housing and community support without requiring participation in treatment or sobriety as preconditions.

Studies to date indicate that Housing First programs that include recovery-oriented assertive community treatment (ACT) are a promising approach (

8,

9,

11). Compared with recipients of standard care—often a continuum of residential settings—recipients of Housing First obtained housing earlier and remained stably housed longer, showed greater reductions in use of health and social services, and reported higher levels of quality of life (

8,

9,

11). However, the evidence base for the effectiveness of Housing First remains limited, consisting of published research from two small trials conducted in New York City and five quasi-experimental studies conducted in other American cities (

12–

19). As well, most of the studies have focused narrowly on housing outcomes.

This article presents the one-year findings from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing the effectiveness of Housing First and treatment as usual across five Canadian cities (

20).

Methods

Study Design and Population

The study design was a nonblind, parallel-group RCT conducted in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal, and Moncton. The cities were chosen to ensure that the study population reflected Canada’s racial and ethnic diversity and was representative of the country’s five regions. Prior to randomization, participants were screened and stratified into high-need or moderate-need groups. This article presents one-year findings for high-need participants who received Housing First that included ACT. In Moncton, the sample was too small to allow for a stratified design, so both high-need (36%) and moderate-need (64%) participants, who received ACT, were included.

High need was defined as a score of less than 62 on the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (MCAS) (

21,

22), assessment of bipolar disorder or psychotic disorder on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview 6.0 (MINI 6.0) (

23), at least two hospitalizations in one year of the past five years, a comorbid substance use disorder, or arrest or incarceration in the past six months. Individuals were referred to the study by health and social service agencies in the five cities.

The sample size in each city was set to 100 individuals receiving Housing First and 100 individuals receiving treatment as usual. Site-level studies were powered to have a minimum of 65 individuals per group, allowing for the detection of a moderate effect (effect size=.5) with a significance level of alpha=.05 and beta=.20, and anticipating about a 25%−30% attrition rate. Approval for the study was obtained from the research ethics boards from the seven institutions of participating researchers.

Eligibility criteria for the study were legal adult status (age 18 or older, except 19 or older in Vancouver); absolute homelessness (no fixed place to stay) or precarious housing (living in a rooming house, SRO housing, or hotel or motel with two episodes of absolute homelessness in past year); a serious mental disorder as determined by

DSM-IV criteria on the MINI 6.0 (

23) at the time of entry; legal status as a Canadian citizen, landed immigrant, refugee or claimant; and no receipt of ACT at study entry.

Intervention Group

Housing First services for the demonstration project were developed on the basis of the Pathways to Housing approach (

10). Rent supplements were provided so that participants’ housing costs did not exceed 30% of their income. Housing coordinators provided clients with assistance to find and move into housing. Support services were provided by using ACT, a multidisciplinary team approach with a 10:1 client-to-staff ratio. At a minimum, study participants agreed to observe the terms of their lease and be available for a weekly visit by program staff. An assessment of fidelity conducted nine to 13 months after the beginning of the study found the programs at all five sites showing on average a high level of fidelity to the Pathways Housing First model (

24). Fidelity assessment entailed site visits by three individuals knowledgeable about Housing First, who rated the programs on 38 Housing First standards related to housing choice and structure, separation of housing and services, service philosophy, service array, and program structure (

25).

Treatment-as-Usual Group

Individuals assigned to treatment as usual had access to the existing network of programs (outreach; drop-in centers; shelters; and general medical health, addiction, and social services) and could receive any housing and support services other than services from the Housing First program. The vacancy rate of rental housing (Spring 2011) was .7% in Winnipeg, 1.6% in Toronto, 2.5% in Montreal, 2.8% in Vancouver, and 4.1% in Moncton (

26).

Outcome Measures

Participants were interviewed in person at study entry and at six and 12 months, and their housing history was documented every three months. Participants were randomly assigned to treatment conditions at the end of the baseline interview by using a computer-generated algorithm programmed into the central data collection system. Interviewers administered a wide range of measures previously used with the population and found to have good psychometric properties (see published study protocol [

20]). The outcomes reported in this article include residence in stable housing (Residential Time-Line Follow-Back Inventory [

27]), quality of life (20-item Quality of Life Interview [QOLI-20] [

28]), severity of psychiatric symptoms (Colorado Symptom Index [CSI] [

29,

30]), substance use (Global Appraisal of Individual Needs–Short Screener [GAIN-SS] Substance Problems Scale [

31,

32]), and community functioning (MCAS [

21,

22]). Stable housing was defined as living in one’s own room, apartment, or house or with family for an expected duration of at least six months or having tenancy rights (holding a lease to the housing). Problematic substance use was defined by the presence of two or more symptoms on the GAIN-SS Substance Problem Scale in the past month (

31).

All of the measures are self-reported except the MCAS, which entails a rating of community functioning by the interviewer. All of the interviewers had previous experience working with the population under study and received extensive initial training, ongoing training, and supervision throughout the trial. The same interviewers interviewed participants from the two groups.

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression was used to test whether participants in Housing First were more likely to be in stable housing at the 12-month interview compared with participants in treatment as usual. The proportion of time spent in stable housing in the first year after treatment entry was also calculated. Analysis of time spent in stable housing was performed by using negative binomial regression, a generalization of a Poisson regression that is appropriate for analysis of count variables that are overdispersed (variance greater than the mean).

Other outcomes were analyzed by using mixed-effects modeling. Because of difficulties in locating participants and scheduling interviews, intervals between measurements varied (six months, standard deviation [SD]=27 days; 12 months, SD=31 days). Follow-up periods were slightly longer for treatment as usual than for Housing First at six months (190 days versus 184 days, respectively, t=3.25, df=885, p<.01) and 12 months (374 days versus 370 days, respectively, t=2.11, df=854, p=.02). Therefore, time was treated as a continuous variable. Models included a random intercept at the person level and a random slope for time. Site was included as a fixed effect. Because time effects were monotonic but often nonlinear, the method of fractional polynomials was used to select the best-fitting one-term transformation of time for each outcome.

Linear mixed-effects models were fit for the QOLI-20, the MCAS, and the CSI. A mixed-effects logistic model was used for the GAIN-SS. The intervention effect in these models was evaluated by including group × time interaction terms, which yielded estimates of the rate of change in each group. These results were then used to calculate the covariate-adjusted difference between groups at the 12-month time point. For continuous outcomes, these differences were divided by the pooled baseline SD to produce effect sizes. Standard errors of predicted differences were calculated by using Stata’s implementation of the delta method (

33).

The sex, racial-ethnic minority status (other than Aboriginal), and Aboriginal status of participants varied across the sites by design, so these variables, in addition to site, were entered as covariates in all analyses. In addition to using the models reported above, the study explored variation in treatment effects by site by using interaction terms. Analyses were repeated after multiple imputation of missing data. Because these analyses did not change the results, the results of the original analysis are presented here. The one-year outcomes reported in this article represent an interim analysis, given that participants were followed for 24 months. As a result, the alpha level for significance for the analyses described in this article was set at .01 in order to preserve an overall alpha level of .05 for the entire study. An alpha level of .04 will be used for the two-year analyses (

34). We conducted the analysis on the principle of intention to treat.

Results

Study Participants

A total of 950 participants presented with high need. These participants were randomly assigned on the basis of an approximately equal allocation (1:1) to either Housing First (with ACT) (N=469) or treatment as usual (N=481) from October 2009 to July 2011. The final sample of 950 individuals represented 95% of the targeted sample (N=1,000). One-year follow-up occurred from October 2010 to June 2012. A total of 856 (90%) participants completed the 12-month follow-up, including 406 of 481 (84%) participants in treatment as usual and 450 of 469 (96%) participants in Housing First.

Table 1 provides a breakdown of the two groups by demographic and clinical characteristics. There were no significant differences between the two groups at study entry.

Housing

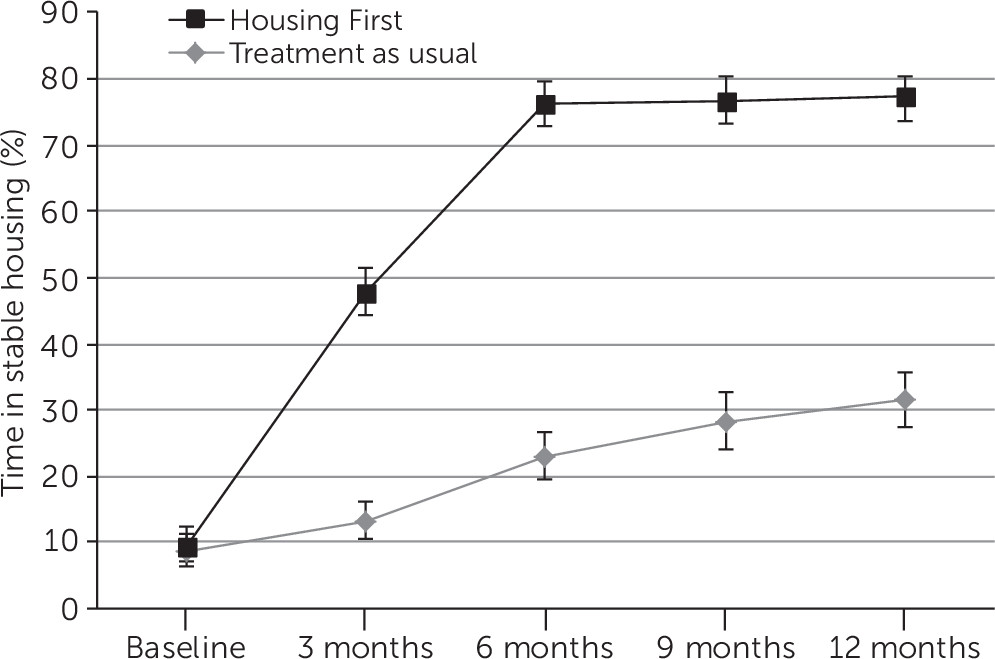

On the basis of participants on whom we had data on their housing situation at the 12-month follow-up, 73% (N=316) of Housing First participants and 31% (N=124) of treatment-as-usual participants resided in stable housing. A logistic regression analysis that controlled for sex, racial-ethnic minority status, and Aboriginal status indicated that Housing First participants were significantly more likely to have stable housing (p<.001, odds ratio=6.35, covariate-adjusted difference=42%, 95% confidence interval [CI]=36%−48%). Of the 116 Housing First participants who were not in stable housing at 12 months, 21 (18%) were staying in shelters, 17 (15%) were in prison or jail, 14 (12%) were in the hospital, and eight (7%) were living on the street. Of the 270 treatment-as-usual participants who were not in stable housing at 12 months, 54 (20%) were staying in shelters, 16 (6%) were in prison or jail, 26 (10%) were in the hospital, and 25 (9%) were living on the street. The mean proportion of time spent in stable housing over the first year was 69% for Housing First and 23% for treatment as usual (

Figure 1). The proportion of time spent in stable housing in the last three months of the year was 77% for Housing First and 31% for treatment as usual. Negative binomial regression confirmed that the difference in consecutive days housed at the 12-month interview was significant (p<.001) and substantial (incidence rate ratio=2.89, covariate-adjusted difference=113 days, CI=67–160). Treatment effects in this model did not vary significantly by site.

Quality of Life

Both Housing First and treatment-as-usual groups reported substantial improvements in quality of life (

Table 2). However, a group × time interaction in a mixed-effects model indicated that the absolute gain was significantly greater among Housing First participants for total score (z=.16, p<.001) and for the subscales related to living situation (z=8.16, p<.001), personal safety (z=4.25, p<.001), and leisure activities (z=3.06, p<.001). Differences between QOLI-20 scores for the two groups after adjustment for baseline QOLI-20 scores, sex, racial-ethnic minority status, aboriginal status, and site are shown in

Table 2. Effect sizes for differences between the groups’ QOLI-20 scores at 12 months (Cohen’s d) were .31 (CI=.16–.46) for total score, .70 (CI=.53–.86) for living situation, .33 (CI=.18–.48) for safety, and .23 (CI=.08–.38) for leisure activities. Both groups also reported substantial improvements in quality of life related to finances, family relations, and social relations, but differences between the groups were not significant. Treatment effects for the quality-of-life outcomes did not vary significantly by site, with the exception of the safety subscale, for which there was some variation in intervention effects across sites.

Community Functioning and Health

Both groups demonstrated improvements in community functioning (p<.001) (

Table 3). Levels of absolute gain were significantly greater among Housing First participants compared with participants in treatment as usual (z=3.05, p=.002). An examination of MCAS subscales revealed significantly greater absolute gains by Housing First participants in social skills (social effectiveness, size of social network, and participation in meaningful activity; z=2.96, p=.003) and behavior (cooperation with treatment providers, substance use, and impulse control; z=3.65, p<.001). Differences between the two groups in community functioning after the analyses adjusted for QOLI-20 scores, sex, racial-ethnic minority status, aboriginal status, and site are shown in

Table 3. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for interactions of group and time were .25 (CI=.09–.41) for total score, .21 for social skills (CI=.07–.36), and .29 (CI=.13–.44) for behavior. Both groups reported decreases in severity of psychiatric symptoms and substance use problems, but the differences between the groups over time were not significant.

Treatment effects for the functioning and health outcomes did not vary significantly by site.

Discussion

Our findings show that Housing First can assist individuals to rapidly exit homelessness even if they are actively symptomatic and using substances (

10). One year after enrollment, Housing First participants were more likely to be housed, had spent a much greater proportion of time stably housed, reported greater gains in quality of life, and demonstrated greater improvements in community functioning compared with participants in treatment as usual. These findings suggest that a majority of individuals with severe mental illness who are homeless are able to move immediately into and manage their own housing if given the right supports. This Canadian study extends the results of previous research conducted in large American cities (

12–

19). The finding that Housing First participants had greater improvements in observer-rated community functioning in the first year of receiving services compared with participants in treatment as usual has not been reported in previous research. These improvements were relatively small in size (d=.25), but they were statistically significant.

Similar to findings of previous research, a minority of Housing First participants (27%) were not stably housed at the one-year follow-up compared with a majority of treatment-as-usual participants (69%). Several factors contributed to housing instability, including loss of initial housing, incarceration, and hospitalization. It is also likely that the low vacancy rates in some cities contributed to housing instability, particularly among treatment-as-usual participants, who did not receive the type of ongoing focused assistance provided to Housing First participants when they were homeless. It is important to note that Housing First programs continue to work with participants regardless of their current housing status (

10). Our findings also showed that participation in a Housing First program produced improvements in overall quality of life and in the quality of specific aspects of life related to housing, safety, and leisure activities. Not surprisingly, the strongest effect on improvements in quality of life among Housing First participants was associated with their living situation (d=.70). In contrast, the effect sizes for safety (d=.33) and leisure activities (d=.23) were relatively small, indicating that Housing First conferred more modest benefits in these two areas of quality of life. It is plausible that Housing First participants felt a sense of greater security and were able to shift their focus toward participating in leisure activities as a result of being housed.

Housing First participants also demonstrated greater improvements in community functioning compared with treatment-as-usual participants. Housing First participants showed larger gains in social skills and in behaviors associated with medication compliance, cooperation with treatment providers, frequency of substance abuse, and impulse control. These findings provided further evidence of the benefits of establishing housing stability. It is important to note that both Housing First and treatment-as-usual participants showed comparable levels of improvement related to the severity of psychiatric symptoms and substance use problems. These findings suggest that treatment as usual is as effective as Housing First in achieving positive clinical outcomes. However, although participants who received treatment as usual and Housing First made comparable gains in severity of psychiatric symptoms and substance use, they did not experience similar reductions in homelessness. In the absence of stable housing, the clinical gains from conventional services may be at greater risk of being lost.

Strengths of the study included the size of the sample, the diversity of the site populations, the low attrition rate, the frequency of data collection, and the range of outcomes, including self- and observer-rated measures. Limitations of the study included the nonblinding of interviewers and participants. Given the nature of the methodology and intervention, it was not possible to hide the treatment condition of participants from interviewers or from themselves. It is possible that a potential bias associated with this nonblinding contributed to differences in quality of life and community functioning between the groups. The relatively short period of time that participants received Housing First was a further limitation.

Conclusions

Housing First services typically focus on assisting individuals to establish stable housing in the first year (

10). It remains to be seen whether Housing First participants will show greater improvements than treatment-as-usual participants on clinical and other outcomes during the second year of this trial. Our interim findings provide support for the redirection of programs and policies toward adopting Housing First to address chronic and episodic homelessness (

7,

35). In fact, as a result of these interim findings, the federal government in Canada has revised its federal homelessness initiative to emphasize the development of Housing First programs (

36).