Associations between second-generation antipsychotic initiation and impaired glucose metabolism have been well documented with adults (

1–

3), yet studies with children and adolescents (

4,

5) have only recently addressed the issue despite evidence that youths’ hormonal and developmental status subjects them to greater metabolic risk (

6,

7). In both randomized and observational studies, second-generation antipsychotics caused a significant increase in the body mass index (BMI) of children and adolescents (

8–

10), and weight gain was pronounced among children who took second-generation antipsychotics in combination (

11). Still, second-generation antipsychotic prescribing continues to increase among children and adolescents (

12,

13), in part because movement disorders have been reported to occur among about one in three children taking a first-generation antipsychotic (

14). By 2009, second-generation antipsychotics were as likely to be prescribed to a child as to an adult during any visit to a psychiatrist (

13).

In February 2004, the American Diabetes Association (ADA), in conjunction with the American Psychiatric Association, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity, released guidelines for monitoring the initiation of second-generation antipsychotics, which included guidance for blood glucose monitoring (

15). The guidelines recommend that prescribers of second-generation antipsychotics screen patients at baseline, 12 weeks postinitiation of medication, and annually thereafter. Prior studies of the effect of the 2004 ADA guidelines showed a small increase in glucose testing of patients initiating second-generation antipsychotics (

16), but monitoring was still underused in populations of adult Medicaid beneficiaries (

17) and commercially insured adults (

18). Among pediatric Medicaid beneficiaries, a study found that 32% of children initiating a second-generation antipsychotic between July 2004 and June 2006 received a blood glucose test between 30 days preinitiation and 180 days postinitiation of the medication (

19).

We sought to evaluate the frequency of both blood glucose and HbA1c testing among commercially insured children and adolescents who began their first course of second-generation antipsychotics before or after the ADA guidelines were issued.

Methods

Study patients were identified in a large, nationwide commercial insurance claims database from United Healthcare. The plan provided full coverage for physician services, pharmacy dispensing, and hospitalizations with varying copays. Claims were linked both longitudinally and for each patient. An active data use agreement was in place, and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

The study population was a cohort of new users of second-generation antipsychotics (risperidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone). We examined the period January 1, 2003, through December 31, 2011; users were ages five through 18. The second-generation antipsychotic initiation date was defined as the day of first dispensing of a second-generation antipsychotic. New use was defined as not having had a dispensing of any second-generation antipsychotic throughout the period preceding the initiation of a second-generation antipsychotic. Patients with less than six months of enrollment in the database before initiation of a second-generation antipsychotic were excluded from the study; therefore, patients could enter the cohort only beginning July 1, 2003. Patients with recorded diabetes also were excluded, and the diagnosis was defined as any one of the following in the baseline period: at least two outpatient diagnoses of diabetes mellitus (ICD-9 code 250X) or one hospital discharge diagnosis of diabetes mellitus or one diagnosis of diabetes mellitus plus dispensing of insulin or an oral antidiabetic. Second-generation antipsychotic dose was not considered.

We identified instances of metabolic screening in the study population by using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) charges for conducting blood glucose and HbA1c tests and which could include such tests as components of test panels. [Detailed information on CPT-4 codes is available in an online supplement.] The study outcomes were glucose or HbA1c tests ordered in the six months before initiation of a second-generation antipsychotic or the six months after initiation. We computed the proportion of patients in each year for whom a metabolic screening test was ordered. We also stratified the analysis by second-generation antipsychotic agent and by psychiatric diagnosis in the years 2005 through 2011. Major psychiatric diagnoses recorded as ICD-9-CM codes at office visits or at hospital discharge were tabulated.

Results

The study population consisted of 52,407 new users of second-generation antipsychotics. The mean±SD age of the cohort was 13.14±3.72 years, and 61% of the study population was male. (Race-ethnicity data are not collected in United Healthcare insurance claims and thus are not reported here.) [Population selection is detailed in a flowchart in the

online supplement.] The most frequently prescribed second-generation antipsychotic from 2003 through 2011 was risperidone, with 21,319 new users, while over the same period 13,464 new users initiated aripiprazole and 12,315 new users initiated quetiapine (

Table 1). A list of the most frequent psychiatric diagnostic codes was compiled for inpatient and outpatient visits (

Table 2). The most common diagnostic code in the study population was affective psychosis (

ICD-9 296.xx), which includes bipolar disorder and major depressive affective disorder. Among patients with one of the most common psychiatric diagnoses, hyperkinetic syndrome (

ICD-9 code 314.xx), glucose testing rates were lowest, at 13.7% preinitiation and 14.3% postinitiation (

Table 2).

Glucose Testing

Averaged over the study period, 16.1% of the population had a blood glucose test in the six months before initiation, and 15.6% had a glucose test in the six months after initiation (

Table 3). From 2003 to 2004, preinitiation glucose screening increased by 1 percentage point, from 17.9% to 18.9%, but the difference was not significant. During the same period, postinitiation glucose testing significantly increased from 14.7% to 16.6% (p=.01). The proportion of preinitiation blood glucose testing was highest in 2004, and the postinitiation testing rate was highest in 2011, when 17.5% of these youths had a claim for a test.

Over the study period, patients receiving aripiprazole had the highest proportion of glucose tests in both the pre- and postinitiation periods, at 14.5% and 14.8%, respectively (

Table 4). Conversely, patients taking olanzapine had the lowest proportion of tests ordered pre- and postinitiation period, at 8.0% and 7.5%, respectively.

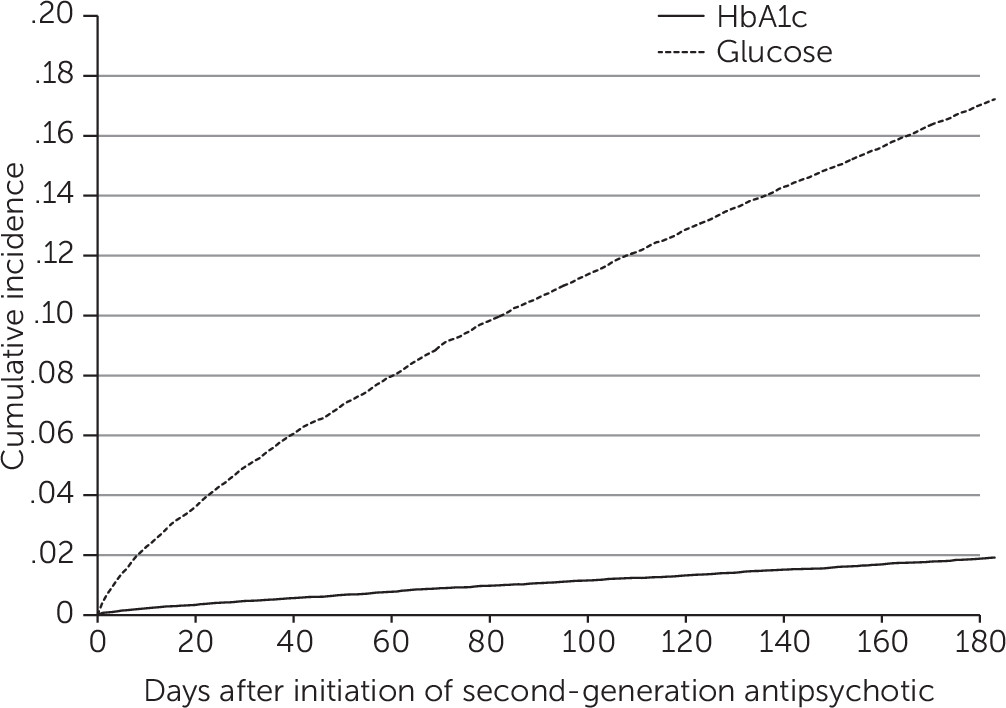

Figure 1 provides the cumulative incidence of glucose testing in the days after initiation of a second-generation antipsychotic. The graph suggests a fairly constant incidence of tests over time, which contradicts adherence to ADA guidelines, which recommend ordering the first metabolic test three months after second-generation antipsychotic initiation.

HbA1c Testing

Overall, the trends in HbA1c testing were similar to those for glucose tests but at a lower level. For example, from 2003 to 2004, preinitiation HbA1c testing rose from .4% to .7% (p=.07) (

Table 3). Over the same period, postinitiation HbA1c testing significantly increased from .6% to 1.1% (p=.01). Pre- and postinitiation HbA1c testing rates were highest in 2011, when 2.0% received a preinitiation test and 2.7% received a postinitiation test.

Discussion

In a commercially insured population of children and adolescents initiating second-generation antipsychotic medications, we found a significant but temporary improvement in blood glucose monitoring for metabolic syndrome immediately after the 2004 ADA guidelines were issued. However, glucose testing rates did not improve again until 2008 and were suboptimal in the overall study period. Considering the guidelines, we found that the average metabolic screening rate over the study period was too low—around 16% for glucose tests and 1.5% for HbA1c tests. The nearly constant incidence in glucose testing over time displayed in

Figure 1 implies that testing is unrelated to typical scheduling of follow-up visits. Therefore, reasons other than initiating a second-generation antipsychotic, such as weight gain, may be the most important determinants of glucose testing. Among youths initiating use of second-generation antipsychotics, those receiving aripiprazole were screened more often than those taking a different antipsychotic. Yet compared with olanzapine, aripiprazole has been shown to be less associated with weight gain and metabolic syndrome (

7). An explanation could be that, because of olanzapine’s harmful metabolic profile (

20,

21), physicians preferentially prescribe it to patients deemed to be at the lowest risk of metabolic side effects, and therefore physicians do not closely monitor for them. Several impactful studies on the comparative safety of second-generation antipsychotics may be responsible for changes in drug utilization over the study period, particularly the decline in prescriptions of olanzapine (

22–

25). One possible reason why children and adolescents with a diagnosis of hyperkinetic syndrome were screened less often than others is that second-generation antipsychotic prescribing for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is intended for shorter periods, such as in response to a behavioral outburst, and concerns of metabolic effects may therefore not factor into treatment decisions (

26).

A prior study of metabolic screening rates for children covered by Medicaid found higher but still suboptimal rates of metabolic screening (

19). Although the study of Morrato and colleagues (

19) is not directly comparable with our own, higher metabolic screening in Medicaid populations compared with commercially insured populations has also been found for adults (

17,

27). Although publicly insured children have been shown to have decreased access to outpatient care (

28), in the case of metabolic syndrome, physicians may consider children covered by Medicaid to be at a higher baseline risk due to their socioeconomic status, making screening more likely (

29). Another reason metabolic screening rates may be higher in Medicaid populations compared with commercially insured populations could be that Medicaid includes more children with severe mental illness. There is evidence that metabolic screening of adult Medicaid patients who have schizophrenia improved dramatically after issuance of the 2004 guidelines (

30) and that screening is more likely for children with a diagnosis of severe mental illness (

31). In these high-risk populations with reduced life expectancy (

32,

33), the metabolic risks of second-generation antipsychotics may have been communicated to patients more clearly.

Our finding of low metabolic screening rates is in line with surveys of practicing physicians, which show a contrast between high awareness of metabolic risks of second-generation antipsychotics and low metabolic monitoring practices (

34,

35). Prior research suggests that potentially important barriers to compliance with treatment guidelines are lack of familiarity or disagreement with the ADA guidelines and severity of the patient’s condition (

36,

37). The importance of addressing these barriers to compliance is underscored by a recent study in a pediatric Medicaid population, which found that use of second-generation antipsychotics with children and adolescents ages six to 17 conferred a threefold higher risk of type 2 diabetes (

5).

Consensus guidelines are one of many ways to change clinical practice. Another way to change clinical practice is through targeted education programs for prescribers, which can address particular groups of physicians directly. Programs on the appropriate use of psychiatric drugs already exist for pediatricians, who often prescribe antipsychotics to children. Such programs may serve as a template for targeted education in other areas of clinical practice (Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project,

www.mcpap.com).

Our results could be explained by other factors for which we could not control. An alternative explanation for the modest improvement in screening over the study period could be the parallel increase in childhood obesity over the same period (

38). An increase in the proportion of obese adolescent patients, more likely to receive metabolic screening because of their weight, would raise metabolic screening rates in the absence of treatment guidelines. We could not adjust for patients’ BMI in our analysis of the claims database. An increase in the rate of type 1 diabetes over the study period could also account for some of the observed increase in glucose testing (

39). In addition, labeling changes to olanzapine and quetiapine in March and December of 2009, respectively, highlighting metabolic risks to children, may have had an impact on screening rates in the later years of the study, although metabolic testing rates did not change significantly in the subsequent years.

Conclusions

In light of the increased use of second-generation antipsychotics and the consolidating evidence of their metabolic side effects, it is concerning that metabolic screening rates through 2011 remained nearly as low as they were before the 2004 consensus guidelines were published. Uncontrolled blood sugar among children has serious consequences, such as weight gain and type 2 diabetes, particularly among those with mental illness, who are already at higher risk of poor health outcomes, thus further emphasizing the importance of metabolic screening.

The mild increase in metabolic testing in recent years parallels a mild increase in childhood obesity and type 1 diabetes (

39,

40), which does not imply a causal relationship but makes for an interesting observation. Although the ADA recommendations of 2004 corresponded with a significant increase in metabolic testing rates, the increase was not sustained in this commercially insured population. The ADA recommendations were focused on adults, however, and in the absence of child-specific guidelines, the recommendations may have been overlooked by providers who treat children. Future work should assess whether the determinants of metabolic screening in a commercially insured population differ from those in the Medicaid population.