Family psychoeducation interventions are associated with positive outcomes for consumers and caregivers (

1) and are recommended by the American Psychiatric Association and the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (

2). The multifamily group (MFG) model of family psychoeducation, endorsed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration as an evidence-based practice (

3), details a multiphase approach. Clinicians first engage with each family in “joining” meetings, followed by an educational workshop for families and consumers who will be participating in the group. The third phase of the MFG model specifies at least nine months of biweekly problem-solving MFGs facilitated by clinicians for families and consumers. By involving several families over an extended period, the MFG model decreases stigma and offers opportunities for mutual support through an expanded social network (

4). The MFG model is associated with lower relapse rates; increased employment rates; improved social functioning; and reduced costs of care (

5), service utilization (

6,

7), and caregiver distress (

8). Consumers who participated in high-fidelity MFGs had better outcomes compared with those receiving low- or moderate-fidelity MFGs (

9).

Despite its demonstrated efficacy, penetration of the MFG model into routine treatment settings has been low. Findings from the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project suggest that the MFG model may be more challenging to implement than other programs (

10). Positive clinician attitudes toward the model, consensus building, and availability of funding have contributed to successful implementation (

11). Barriers to family psychoeducation exist across the mental health system, including stigma, time and financial pressures on the family, lack of staff training and gaps in agency infrastructure, and inadequate resources or attention at the level of the state mental health authority (

1,

5,

12). A recent review noted that the lack of published evaluation data on large-scale implementations of family psychoeducation limits the information available about potentially effective strategies to guide future implementation efforts (

13).

The Family Institute for Education, Practice and Research (FIEPR), established by the New York State Office of Mental Health in partnership with the University of Rochester Medical Center and with the collaboration of the Conference of Local Mental Hygiene Directors and the National Alliance on Mental Illness–New York State, is charged with promoting access to family services in mental health settings. FIEPR’s first project focused on implementation of the MFG model in outpatient mental health programs (

14). We report findings from the first large-scale prospective implementation study of MFG fidelity outcomes over time. In addition, we examined the relationships between organizational characteristics and fidelity outcomes and between time to implement MFG milestones and successful implementation of MFGs. Finally, we explored the impact of two consultation formats on fidelity outcomes.

Methods

The research protocol was approved by the University of Rochester’s Research Subjects Review Board.

Participants and Study Sample

FIEPR solicited requests for proposals for a statewide MFG implementation initiative in spring 2003. Seventeen of 52 applications (33%) were accepted, representing 37 outpatient mental health programs. Sites were selected to achieve diversity in size, location, and treatment environment. Thirty-one sites enrolled in the project. No data are available on the six nonenrolled sites.

Project Activities

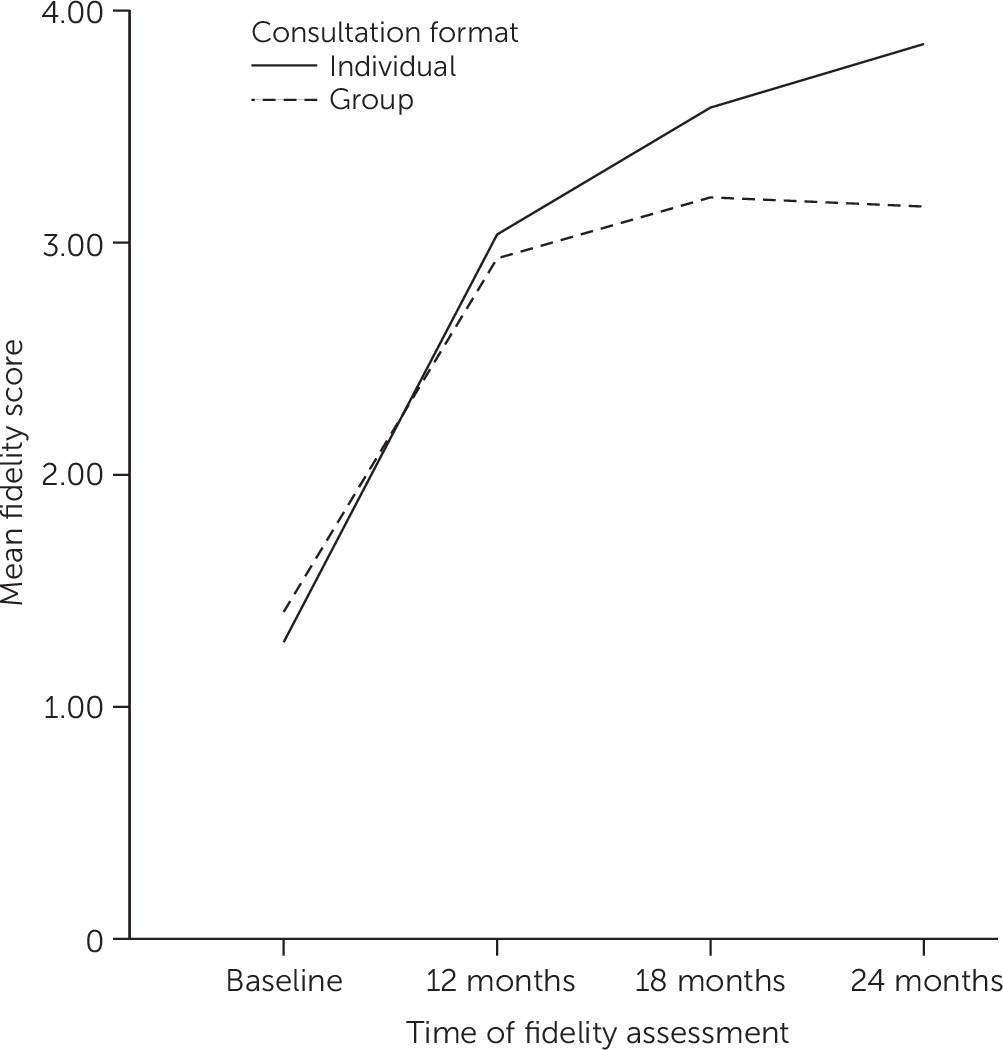

The implementation model was informed by the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project (

15). Each participating agency was required to establish an implementation team to oversee project activities. FIEPR staff conducted initial site visits and two-day trainings beginning in fall 2003, followed by monthly expert consultations either with individual implementation teams (15 sites) or in groups of four implementation teams (16 sites that were already participating in a regional behavioral health consortium). Thus assignment to the consultation format was not random. Consultation sessions were facilitated by experts in the MFG model who modeled problem-solving strategies that mirrored the MFG approach to address implementation challenges. Monthly consultation with individual teams took place via face-to-face meetings at each site with project coordinators, supervisors, and frontline practitioners. Monthly consultation with groups of teams occurred in face-to-face regional meetings with site project coordinators and supervisors only. FIEPR staff also facilitated regional, quarterly, face-to-face meetings for project coordinators from all participating sites and provided ad hoc consultation by telephone and e-mail. Participating sites were expected to achieve implementation of all key components of the MFG model over the course of the 18-month project, including joining sessions with families, an educational workshop for families and consumers, and at least nine months of one or more MFGs.

Measures

Fidelity to the MFG model was assessed by using the Family Psychoeducation Fidelity Assessment Scale (

10). The scale includes 14 items reflecting structural and clinical components of the model—for example, content of joining sessions with families, use of a structured group process, and frequency and length of MFGs. Each item is scored from 1 to 5 according to specific anchors, with higher scores representing higher fidelity to the model. Fidelity data were collected by research staff via telephone interviews with one or more key informants at each site at baseline and 12, 18, and 24 months. Key informants included the site director, family psychoeducation coordinator, or other staff knowledgeable about the implementation. Items were scored independently by at least two research staff, who then determined a consensus score. Interrater reliability was assessed with intraclass correlation (ICC 2,K) by using the consensus rating. An ICC of .95 was achieved for the 12-, 18-, and 24-month fidelity assessments, but the ICC was considerably lower at baseline (.67) due in part to challenges rating programs’ existing work with families.

Overall fidelity was calculated by using the mean score across all scale items. Following McHugo and colleagues (

10), scores of ≥4 were classified as high fidelity, scores of 3 to <4 as moderate fidelity, and scores <3 as low fidelity. For intent-to-train analyses, we used the last available fidelity assessment to characterize program fidelity.

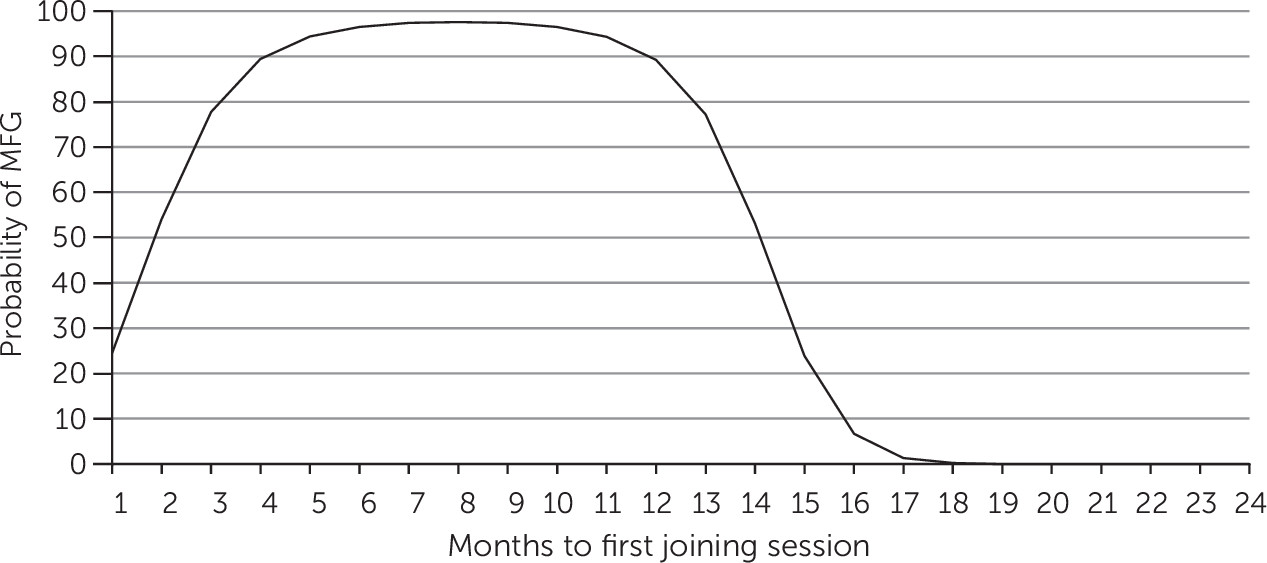

Research staff documented the time required to implement key MFG milestones, recording the time in days from each site’s staff training to the site’s first family joining session, family educational workshop, and MFG meeting. Time in days was converted to months by dividing by 30.

Organizational characteristics were taken from a survey completed by site administrators at baseline and 12 and 24 months. The first available observation was used to characterize participating organizations. Variables selected for inclusion were geographic setting (rural, suburban, small city, or urban), total annual operating budget for the entire organization in dollars, number of consumers served by the entire organization each year, and number of full-time-equivalent staff (FTEs). Prior experience with the MFG model was operationalized (yes or no) by asking, “Have you tried to implement MFG before?”

Analysis

Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted in SPSS 19.0, and multivariate analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4. Descriptive univariate analyses provided proportions for categorical variables and minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviations for continuous variables. Bivariate tests of association were conducted to examine relationships between organizational characteristics and fidelity outcomes. Logistic regression was used to assess whether time from staff training to a site’s first joining session predicted implementation of at least one MFG. Based on post hoc analyses, a quadratic term squaring the time to first joining session was added to the model to test for a curvilinear relationship (

16). Model fit statistics were calculated to compare the linear and curvilinear models to determine the best fitting model. Finally, fixed-effects multilevel regression models were estimated, nesting fidelity assessments over time by site, to assess changes in fidelity over time and differences in fidelity by consultation format.

Discussion and Conclusions

Despite the strong evidence base for numerous interventions to improve outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness, dissemination of these practices has lagged (

17). Barriers to implementation of the MFG model of family psychoeducation have been identified across levels of the mental health system, including characteristics of the intervention itself; characteristics of practitioners, consumers, and families; the agency context; and the larger systems environment (

18). Few studies have reported on implementation and fidelity outcomes of the MFG model. This study attempted to address that gap.

This is the first large-scale study to examine fidelity outcomes of an MFG implementation. Although the findings are promising, outcomes of the New York State MFG initiative reinforce findings in regard to the challenges associated with “research to practice” efforts. Because 11 of the 31 sites (36%) failed to conduct at least one MFG, future projects should consider the potential for failure to achieve project milestones when establishing target numbers for site recruitment. Prior clinic experience with MFG psychoeducation was associated with higher fidelity, perhaps resulting from a “practice effect” or an organizational culture more favorable to the MFG model. Twenty of the 31 sites (65%) achieved moderate- to high-fidelity outcomes, and the same number succeeded in conducting at least one MFG. This suggests that implementation of the MFG model is feasible in routine outpatient mental health settings. However, sites struggled to implement certain clinical components of the model. Given the relationship between clinician adherence to the MFG model and client outcomes (

9), this may be an important area for technical assistance in future implementations. Fidelity ratings and milestone achievement did not always align, reflecting the multidimensional nature of the Family Psychoeducation Fidelity Assessment Scale; some sites with low overall fidelity succeeded in conducting at least one MFG, whereas others with higher fidelity did not. More research is needed to assess the contribution of MFG model elements to family and consumer outcomes as well as potential adaptations that may yield benefits but require less intensive implementation.

This project also highlights the importance of timing when planning and conducting implementation of the MFG model. The mean time from staff training to conducting the first MFG was just under one year, similar to other reported implementations (

19); however, at 12 months half of participating sites were rated as low fidelity. This suggests that sites implementing the MFG model may require support past the one-year mark. The curvilinear relationship between time to first joining session and probability of conducting an MFG is of particular interest. Programs that moved too quickly may not have allowed enough time for careful planning and sustainability, whereas programs that moved too slowly may have lost momentum or suffered from competing priorities that interfered with implementation success.

The consultation format findings indicate that this may be in an important area for future study. The mean overall fidelity score for programs receiving group consultation plateaued in the second year of implementation but continued to increase among sites receiving individual consultation—approaching scores observed for family psychoeducation sites in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project at 24 months (4.0±.58) (

10). The continued increase among sites receiving individual consultation may reflect greater engagement of frontline staff in that format. Given the resource demands of individual site consultation, it is encouraging that the sites receiving group consultation used in New York State did not result in statistically worse fidelity outcomes than sites receiving the individual consultation format. There is some evidence to suggest that programs may vary in the extent to which they utilize consultant resources to promote fidelity, even within individual consultation approaches (

20). Identifying effective and efficient means of providing support to sites implementing evidence-based practices is a critical area of implementation science.

State evaluation of program implementation can inform future planning and resource allocation and provide data on effectiveness of current programs. At the same time, given the demands of a large-scale implementation initiative, evaluation may be underresourced. Data collection protocols should account for time and resource constraints of local site administrators. For example, this study found that telephone interviews were able to identify both high- and low-fidelity MFG implementation with high levels of interrater reliability. New York State’s experience with MFG implementation suggests that states should clarify expectations of participation, track time to implement specific milestones, and consider multiple methods of operationalizing implementation outcomes.

This study had several limitations. Lack of data on nonparticipating organizations made it difficult to assess the representativeness of the sample. Furthermore, participating agencies volunteered to be part of the project and were selected through a screening process. Results may therefore not be generalizable to other settings, either in New York State or elsewhere. Eight sites did not respond to the administrative survey, resulting in less power to detect relationships between organizational characteristics and fidelity. Telephone-based fidelity assessments, such as those used in this study, have been used in research on other evidence-based practices but have not yet been validated for the Family Psychoeducation Fidelity Assessment Scale, and comparisons to studies using other methods should be made with caution. Power considerations or the need for a longer-term follow-up may have contributed to the lack of a finding regarding the consultation format. Finally, fidelity outcomes used in this study have not been assessed relative to client outcomes.

This study offers a number of promising areas for further research. Exploring factors associated with milestone achievement and agencies’ perceived needs for implementation support may be useful when planning future statewide implementations. In particular, different types of barriers may exist at different levels of fidelity; for example, sites may overcome certain barriers to implement with moderate fidelity but confront different challenges when attempting further improvement. The growing literature on organizational factors associated with successful implementation suggests that the context in which clinical practice occurs both shapes and is shaped by implementation initiatives and is an important area for more in-depth research. Finally, exploring the relationship between consumer outcomes and varying levels of fidelity to the MFG model as defined by the Family Psychoeducation Fidelity Assessment Scale, in terms of both overall fidelity and specific fidelity items, is needed to inform implementation decisions for both state policy makers and agency leadership.