Community mental health organizations face increasing challenges as a function of governmental oversight and accountability associated with funding of services. This scrutiny results in increased burden (such as increased administrative work and productivity requirements) and demands (including following national guidelines and accountability to funders) on mental health organizations and direct service providers (

1). Increased burden and demands may contribute to a stressful organizational climate, defined as perceptions of, and emotional responses to, an overwhelming work environment (

2–

4), that may in turn result in decreased commitment to an organization and its goals (

5,

6). Meta-analytic research on stressful organizational climates has demonstrated negative consequences, including lower job satisfaction and service quality (

7). The relationship between stressful organizational climates and reduced organizational commitment is one of the most corroborated (

6,

8–

10). Organizational commitment, defined as a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization and a strong desire to remain a member of the organization (

11), is correlated with improved workforce stability, job performance, and service quality, as well as lower job burnout and use of sick leave (

3,

12–

18), and is one of the strongest predictors of staff turnover (

3,

14,

15). Hence it is imperative to understand how organizational stress and other factors may affect organizational commitment among desirable employees, including those high in adaptability, a trait associated with more positive attitudes toward evidence-based practices among mental health providers (

19) and with better work performance (

20).

Mental health organizations undergo frequent transformations (

21), necessitating a workforce that can be flexible in adapting to change. We define individual adaptability in line with the definition from Baard and colleagues’ review (

22) as a tendency to make “cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioral modifications . . . in response to the demands of a new or changing environment, or situational demands.” Adaptability is related to a number of important personal constructs, such as task orientation, conscientiousness, and satisfaction (

23). Further, workers higher in adaptability and psychological flexibility demonstrate better mental health, motivation, job performance, innovation, and creativity, as well as reduced absence rates and reduced turnover intentions (

24–

26). In a study examining the role of emotional competence, personality, and job attitudes as predictors of job performance, the adaptability component of the Emotional Competence Inventory was the single strongest predictor of job performance ratings among public-sector factory workers (

20). Hence studies suggest that individual differences in adaptability play an important role in both individual and organizational performance. In addition, the association of individual adaptability with reduced absenteeism and turnover intentions in corporate settings suggests that mental health provider adaptability may increase provider organizational commitment. However, it is unknown how provider adaptability may operate within the context of stressful organizational climates in community mental health settings.

Previous research in the health care field has found a negative relationship between organizational stress and organizational commitment (

6,

8), such that employees reporting high job stress were more likely to exhibit lower organizational loyalty (

8). A stressful organizational climate, as measured by the Organizational Social Context (OSC) scale (

11) comprises emotional exhaustion, role conflict, and role overload. Respectively, these factors relate to feeling overwhelmed, experiencing multiple conflicting demands, and having impossible amounts of work to accomplish (

11). In meta-analyses, role conflict was positively correlated with both job dissatisfaction and job-related tension (

27), and role conflict and role overload were negative antecedents of organizational commitment (

9). Although previous research has found adaptability to be a desirable characteristic among workers (examples include increasing positive attitudes toward evidence-based practice and decreasing intentions to switch jobs), it is still unclear how adaptable workers operate within stressful organizational climates. For example, the same characteristics of adaptability that lead to positive employee attributes in a workplace, such as flexibility and ability to manage change well, may also lead to exercising discretion, manifesting as willingness to change jobs in situations where the worker perceives the current work environment to be untenable (

28). As such, although workers higher in adaptability may be more likely to accept change and new initiatives, they may also be more likely to engage in active strategies to find other employment and pursue alternatives that are more in line with their career goals when the work environment is overly stressful (

28,

29).

In this study we examined the relationships between stressful organizational climate, provider adaptability, and organizational commitment. In accordance with previous literature, we hypothesized that higher levels of stressful organizational climate would be negatively related to organizational commitment. We also hypothesized that provider adaptability would be positively associated with organizational commitment. Finally, we hypothesized that organizational stress would moderate the relationship between provider adaptability and organizational commitment such that providers with higher levels of adaptability would have greater levels of organizational commitment when organizational stress is low but be less committed than those who are less adaptable when organizational stress is high.

Methods

Participants

Participants were clinical and case management service providers working in public-sector mental health programs for children and their families in a large California county between November 2000 and September 2001 (

30). The county provided the research team with a list of all county-operated and county-contracted mental health programs providing services to children and families (N=54). Managers from each mental health program were contacted and provided with a detailed description of the study, which aimed to examine organizational characteristics among mental health programs for children and families by using survey methods. Forty-nine of the 54 programs (91%) agreed to participate in this study and provided time during work hours for their clinicians and case managers to complete the survey. Program types included outpatient (42%), day treatment (21%), wraparound (19%), case management (17%), and inpatient (2%). A total of 335 clinicians and case managers worked within the 49 programs that agreed to participate, and 96% of clinicians (N=322) consented and participated in the study. Complete data on all variables of interest were available for 311 (93%) of the 335 clinicians and case managers from participating programs.

Chi-square and t test analyses comparing providers who had missing data for at least one variable with those who had complete data revealed no significant differences in demographic variables, work characteristics, or variables examined in the primary analysis. The number of mental health providers at each program ranged from one to 72 full-time-equivalent employees (M±SD=14.6±16.2). Clinicians and case service managers who did not work for a county-operated or county-contracted mental health program serving children and families (out of private practice, military organizations, adult treatment programs) were excluded from participating in this study.

Procedures

Using a county-provided list of all county-operated and county-contracted mental health programs serving children and families, we contacted a program manager at each program and described the study in detail. Survey sessions were scheduled at the program site at a time designated by the program manager, and surveys were administered to groups of direct-service providers without supervisors present. The project coordinator and a trained research assistant administered pen-and-paper surveys, assuring participants of confidentiality and emphasizing the need to answer honestly, and were available during the survey session to answer any questions that arose. Participants received a verbal and written description of the study and provided informed consent prior to the survey administration. The study and procedures were approved by the appropriate institutional review boards.

Measures

Organizational stress.

The OSC scale was used to assess organizational stress. The factor structure of the OSC scale has been confirmed in a large national sample of 100 mental health agencies (

11). OSC subscales of role conflict (for example, “Interests of the clients are often replaced by bureaucratic concerns such as paperwork”; seven items, current sample α=.85), role overload (for example, “The amount of work I have to do keeps me from doing a good job”; seven items, current sample α=.84), and emotional exhaustion (for example, “I feel emotionally drained from my work”; six items, current sample α=.90) create the OSC stress measure (current sample α=.93). All 20 items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0, “not at all,” to 4, “to a very great extent,” with the stress score calculated as the average across all items. In addition, we provide the T score for the sample to enable comparison with the national sample.

Adaptability.

The adaptability subscale of the Emotional Competence Inventory (

31) was used to measure the extent to which providers are flexible in handling change and new circumstances in the work environment (items include “smoothly juggles multiple demands” and “adapts by changing overall strategy, goals, or project to fit situation”; five items, current sample α=.62). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0, “not at all,” to 4, “to a very great extent,” with provider adaptability scores calculated as the average of all items.

Organizational commitment.

The organizational commitment subscale of the OSC scale was used to assess the extent to which a provider is committed to the agency (examples include “I am proud to tell others that I am a part of this organization” and “For me this is the best of all possible organizations to work for”; eight items, current sample α=.91). The subscale has excellent psychometric properties, has been used in numerous studies in children’s mental health and social services, and has been shown to be related to staff turnover (

3). Each item is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0, “not at all,” to 4, “to a very great extent,” with the organizational commitment score calculated as the average of all items.

Analyses

Moderated regression analyses were conducted to examine the associations of provider adaptability and organizational stress with organizational commitment as well as the moderating effect of organizational stress on the relationship between provider adaptability and organizational commitment. Aggregation analyses were conducted because organizational stress is believed to represent a team-level construct (

11). In order to examine this assumption, we computed the average within-group correlation (a

wg) and the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the stressful climate measure. The a

wg interrater agreement statistic was used to assess the degree to which members within each program agreed in their responses to the stressful climate scale. In order to facilitate interpretability and comparability to other reliability and consistency measures, we scaled the a

wg statistic with a range of 0 to 1, where 1 indicates perfect agreement and .70 indicates moderate agreement (

32).

Because providers were nested within mental health programs, multilevel hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) analyses were conducted to control for the effects of the nested data structure (

33–

35). Provider age, gender, and months working in the agency were included in the analyses as control variables. HLM analyses were conducted with maximum marginal likelihood estimation for mixed-effects models in IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (

36). The final model included participants with no missing data (N=311). An unconditional model including only the intercept was estimated to compute the ICC for organizational commitment.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Seventy-six percent (N=237) of the sample was female. The race-ethnicity of the sample was non-Hispanic Caucasian (62%, N=193), Hispanic (13%, N=42), African American (7%, N=22), Asian American (6%, N=18), American Indian (1%, N=2), other race-ethnicity (7%, N=22), and not reported (4%, N=12). The mean±SD age for the sample was 35.93±10.68 years, and the mean job tenure was 23.4±37.6 months. Provider education for the sample included those with a master’s degree (57%, N=178), college graduates (19%, N=59), and those with some graduate work (11%, N=33), a doctoral degree (10%, N=30), or some college (3%, N=10). Thirty-two percent of the sample (N=100) reported that their primary discipline was marriage and family therapy, 31% (N=97) social work, 21% (N=65) psychology, 13% (N=39) other (drug or alcohol counseling or psychiatry), and 3% (N=10) not reported.

The average OSC stress score was 1.37±.79. The average T score utilizing the normative national sample was 47.20±9.57. The average provider adaptability score was 2.52±.55, with higher scores signifying higher levels of provider adaptability, and the average level of organizational commitment was 2.57±.76, with higher scores indicating greater commitment to one’s organization.

Multilevel Regression Analyses

The ICC for the unconditional HLM model was .10, indicating that 10% of the variance in organizational commitment was accounted for by mental health program. There was moderate agreement across mental health programs on organizational stress (a

wg=.73, ICC=.11). The first step in the HLM model examined whether stressful organizational climate was negatively associated with organizational commitment, as well as whether provider adaptability was positively associated with organizational commitment (

Table 1). A strong negative relationship was found between stressful climate and organizational commitment (B

=–.54, p

<.01

); however, no significant relationship was found between adaptability and organizational commitment when analyses controlled for the effects of organizational climate, mental health program clustering, age, gender, and tenure at an organization.

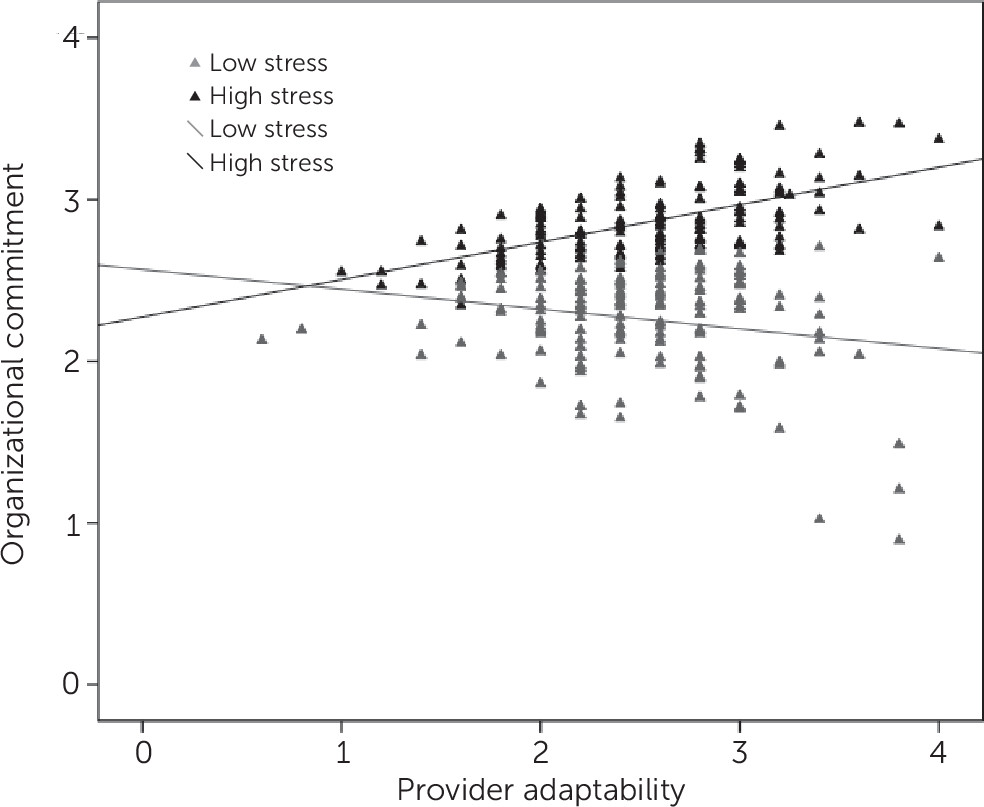

The second step in the model tested the hypothesis that stressful climate would moderate a relationship between provider adaptability and organizational commitment. This analysis revealed a significant positive relationship between provider adaptability and organizational commitment (B=.36, p<.01). However, this effect should be viewed within the context of the significant interaction effect between adaptability and stressful climate (B=–.17, p<.05). Compared with those lower in adaptability, providers with higher levels of adaptability reported reduced organizational commitment when organizational stress was high and increased organizational commitment when organizational stress was low. To examine this interaction graphically, we used a median split on the organizational stress variable, categorizing providers into high (top 50%) and low (bottom 50%) levels of organizational stress.

Figure 1 displays the relationship between provider adaptability and the HLM predicted values for organizational commitment by high and low stress.

Discussion

Although significant relationships with organizational commitment were found between provider adaptability and stressful organizational climate in HLM models with and without the interaction term, respectively, the relationship among the variables is best explained by the significant interaction effect rather than main effects. Examining the moderating role of organizational stress revealed that although adaptability was associated with higher organizational commitment at lower levels of organizational stress, it was associated with lower organizational commitment at higher levels of organizational stress. It may be that providers high in adaptability do well at adapting to their work environment when it is more functional, enhancing commitment; however, in line with the work of Fugate and colleagues (

29), flexibility and openness to change may allow providers to exercise more discretion regarding employment options when they perceive their work environment as stressful. Alternatively, providers lower in adaptability may be more likely to avoid change, even within the context of a stressful organizational climate. Such findings suggest that organizations characterized by role overload, role conflict, and emotional exhaustion may be in danger of losing providers who are more adaptable.

Implications for Practice

We argue that efforts should be made to retain adaptable providers, in that adaptability is associated with positive worker attributes, such as occupational preparedness, job satisfaction, and organizational performance (

23,

37). The loss of such individuals is detrimental to community mental health agencies because they are more likely to be open to evidence-based practice implementation (

38), they have higher work-team performance and productivity (

39), and their loss raises mental health care costs for agencies and consumers (

40). Given the moderation effect of stressful climates on the relationship between provider adaptability and organizational commitment, mental health programs should assess and understand their organizational climate and intervene when necessary to reduce stressful climates.

Competing work demands in community mental health service systems often come in the form of increased clerical and administrative duties and productivity demands (

41,

42). These factors may lead to more stressful climates and may be untenable for providers whose primary training lies in the provision of direct mental health services. Organizational interventions can be implemented to assist providers in using structured methods to streamline record keeping and reporting of data.

Although organizational stress-reduction interventions are understudied compared with individual stress-reduction techniques (

43,

44), possible strategies that organizations can use to reduce stressful organizational climates include redesigning tasks, redesigning the work environment, establishing flexible work schedules, encouraging participative management, including the employee in career development, analyzing work roles and establishing goals, providing social support and feedback, building cohesive teams, establishing fair employment polies, and sharing the rewards (

45). These strategies are often an incentive for organizations to build a more employee-empowered culture (

43). A more specific example is the ARC (availability, responsiveness, continuity) organizational intervention (

46). The ARC organizational intervention has been shown to improve the organizational climate of human service organizations, resulting in improved staff retention and client outcomes and facilitation of the outcomes of evidence-based practice implementation (

4,

47).

Limitations

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, only cross-sectional data were collected; therefore, causality cannot be inferred. Second, all variables were based on respondent self-reports, and therefore common method variance may have influenced the results presented here. However, we attempted to minimize this potential bias by using one of Podsakoff and colleagues’ (

48) approaches for increasing procedural control and promoting accurate and unbiased responses, “protecting respondent anonymity and reducing evaluation apprehension.” Surveys were administered in groups without the presence of supervisors, respondents were assured that they would be identified only by a researcher-generated number, and research staff reinforced the importance of honest responding and asking questions. Future research using more objective measures, such as organizational turnover rates, and corroborative methods should be used to confirm results obtained on the basis of self-report data (

49,

50). Finally, this study took place in one county mental health system, and results may not generalize to other geographic areas or service sectors. However, these results may inform studies in other sectors and service systems, given that workforce issues are often common across service sectors and types.

Conclusions

Service systems are becoming increasingly demanding for mental health service providers. For example, the Affordable Care Act has increased the impetus for integration of mental health, substance abuse treatment, and general medical services. Major initiatives have emerged to increase the implementation and sustainment of evidence-based practices in mental health systems and organizations. Such demands and efforts are fraught with complexity, and it is clear that approaches for decreasing work stress and facilitating the delivery of high-quality mental health services are needed. Organizations can work strategically to develop supportive organizational climates that reduce stressfulness and increase functionality. Such a course of action is needed to reduce emotional exhaustion, role conflicts, and role overload and to retain adaptive providers in the workplace so that they may provide high-quality care and continuity in the delivery of mental health services.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01MH072961 and K01MH001695 (Dr. Aarons, principal investigator). The authors thank the organizations, supervisors, and service providers who participated in the study and made this work possible.