The stigma of mental illness has an egregious effect on people labeled with psychiatric diagnoses, including robbing them of life opportunities necessary to achieve goals related to work, independent living, relationships, and health (

1). Therefore, erasing the stigma of a mental illness is a major public health priority. Language, and more specifically word choice, is often targeted as one way to diminish stigma. For example, person-first language (“persons with mental illness” versus “the mentally ill”) has become the standard for referring to people with disabilities in research, policy, and advocacy efforts, because this phrasing emphasizes the human aspects of the person over the disabling condition (

2). In addition, Japanese psychiatrists have replaced the word “schizophrenia” with the term “integrative disorder” in order to decrease stigma (

3), and scholars in the United States have advocated for similar changes in terminology of mental illness (

4).

Recently, the word “stigma” itself has been proposed as a stigmatizing word. Stigma implies a mark that places responsibility for prejudice and discrimination with the person rather than with his or her society (

5). Stigma also seems to be a word primarily aimed at mental illness rather than at other health conditions (

6). Thus, in 2008, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) removed the word “stigma” from their Resource Center to Address Discrimination and Stigma (ADS Center) in response to these concerns. Since then, SAMHSA seems to have intentionally avoided using “stigma” in public documents. Some advocates suggest that words such as “prejudice” and “discrimination” are suitable replacements for “stigma.”

Although steps toward more politically correct language are well intentioned, policy commitment is best informed by empirical research. Japanese efforts at relabeling schizophrenia, for example, seem to have resulted in favorable changes in attitudes toward individuals with the disease (

3,

7). Thus the question remains: Is “stigma” a stigmatizing word? This study examined this question empirically through a nationwide survey. Specifically, we tested whether the public would endorse more negative attitudes or behavioral intentions toward an individual with schizophrenia when that individual was described as worried about “stigma” versus about “prejudice” or a more generic term, “reactions.”

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained through the Illinois Institute of Technology, and data collection was completed in June 2015. Amazon Mechanical Turk (Mturk) survey participants from throughout the United States (N=340) provided online written consent for the survey and were randomly presented with one of three vignettes describing Harry, an employed, middle-aged man with schizophrenia. The vignettes, adapted from the short version of the Attribution Questionnaire (AQ-9), were identical except for the final sentence, which read, “He [Harry] sometimes worries that he will experience [stigma/prejudice/reactions] from his coworkers.” Immediately after reading the vignette, participants completed the AQ-9 as a measure of stigma. Responses to the AQ-9 are on a scale from 1 to 9. Possible scores range from 9 to 81, with higher scores indicating higher stigma endorsement. Regardless of condition, participants then rated how disrespectful they found each word: “stigma,” “prejudice,” and “reactions.” Possible scores ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater disrespect.

To ensure participants had sufficient attention to task, attention checks were embedded in the survey. Of the 397 individuals who began the survey, 30 were directed to exit the survey without pay after the initial attention check; all other participants were compensated through Mturk. An additional 27 participants entered insufficient data for inclusion in the analyses, resulting in 340 valid surveys.

Results

Participants’ mean±SD age was 35.00±11.44, with a fairly equal distribution between males (N=166, 49%) and females (N=171, 50%). Most participants (N=311, 92%) identified as non-Hispanic/non-Latino, with 283 (83%) identifying as white, 33 (10%) as black, and 21 (6%) as Asian. Forty-one participants (12%) reported having a mental illness. The two most common categories of marital status were single (N=156, 46%) and married (N=115, 34%). Most participants (N=269, 79%) reported some undergraduate college education. Over half (N=195, 57%) were working full-time, with a comparable percentage (N=191, 56%) reporting income levels between $10,000 and $49,999.

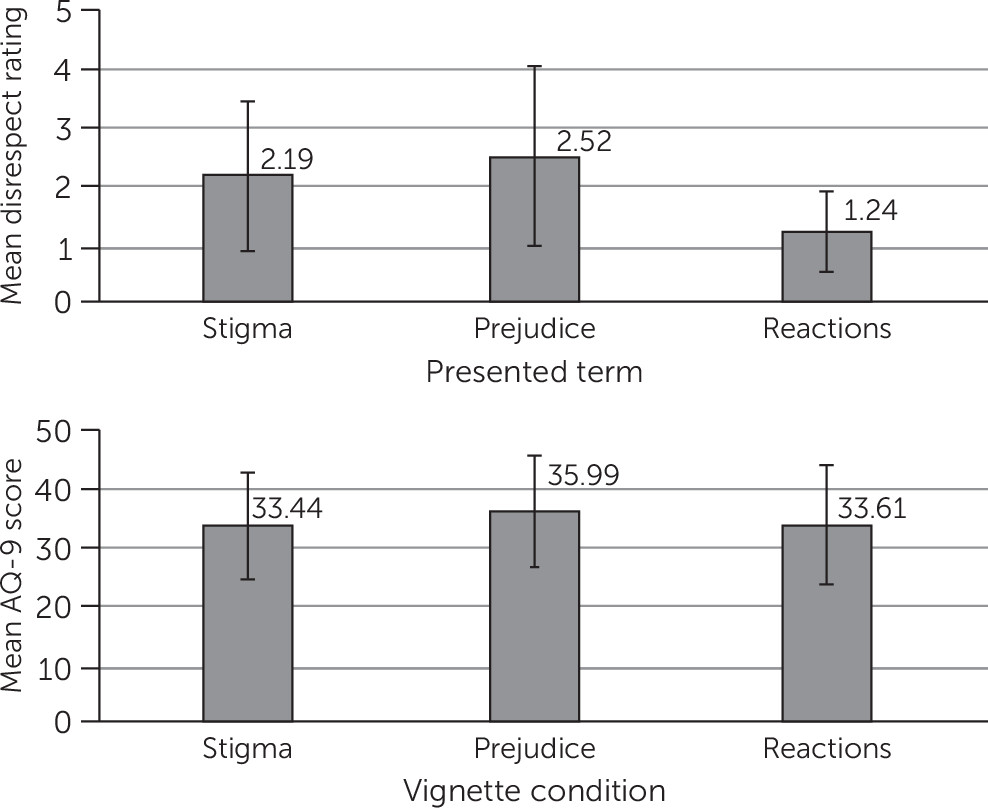

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 22. Means and standard deviations across conditions are summarized in

Figure 1 for the AQ-9 and for perceptions of stigma-related terms. Scores on the AQ-9 closely approximated those of other recent community (34.8±7.5) and student (34.7±9.8) samples (

8). To check for balance of sample characteristics across experimental groups, we tested for differences in gender and ethnicity, neither of which was significant. A one-way between-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted across the three vignette conditions with the AQ-9 as the outcome variable. No significant differences were observed between the three vignette conditions.

To analyze participants’ perceptions of the three words (“stigma,” “prejudice,” and “reactions”), a within-group ANOVA was conducted for disrespect ratings. The analysis determined that mean disrespect ratings differed significantly between the three terms (F=199.09, df=2 and 554, p<.001). Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction revealed that “prejudice” was viewed as significantly more disrespectful than both “stigma” and “reactions” (2.52±1.28, 2.19±1.52, and 1.24±.68, respectively, p<.001 for both comparisons). The word “reactions” was viewed as significantly less disrespectful than both “stigma” and “prejudice” (p<.001).

Discussion

This study examined how the word “stigma” affects public attitudes and behaviors toward individuals with mental illness. Results showed no significant differences between groups as measured by the AQ-9. Participants who read the “stigma” vignette did not have a higher AQ-9 score than those who read the “prejudice” and “reaction” vignettes. Ironically, participants rated the word “prejudice,” a touted replacement for “stigma,” as being more disrespectful than the two other words. The methods used in this study were intended to capture both attitudinal responses (through the AQ-9) and behavioral responses (through the disrespect ratings) to three different stigma-related terms.

An obvious limitation of this study is the interpretation of nonsignificant results. Our vignette manipulation may have been insufficient to fully simulate the real-world connotations of these terms. AQ-9 scores of participants who read the “stigma” vignette may not have indicated a higher level of stigma because they viewed stigma as an action against the character, rather than as a reflection of his identity. Other factors for which we did not control, such as social desirability, could also have contributed to an inability to reject the null hypothesis.

Research validating the use of MTurk workers for social science research has shown modest differences in data quality, with sample diversity superior to that of other data collection methods (

9,

10). Heeding recent research on the importance of quality safeguards (

11), we embedded attention check questions and excluded data from participants who failed these questions. Given that AQ-9 mean scores were consistent with those of recent studies, we have reasonable confidence that this sample roughly represented the general public. However, compared with the U.S. population, our sample had notably fewer people of color and a slightly younger mean age, which limited generalizability. Inclusion of a sample that has been shown to have more stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs about mental illness (for example, older adults and Latinos) might have led to different results (

11).

Inadequate statistical power may have constrained our ability to show significant differences between subgroups in our sample. A sensitivity analysis indicated that the study was sufficiently powered to detect effect sizes on the order of d=.30, which is within the range of effects achieved through antistigma interventions (

12). A larger sample may have revealed differences not apparent in our data; however, small effect sizes may be of limited practical significance.

In light of our findings, further empirical guidance should precede systemic policy change to censor the word stigma. Unnecessary terminology changes cause confusion for researchers, advocates, and other stakeholders fighting against stigma. A focus on semantics may detract from the larger issues that substantially and materially disrupt the lives of people with mental illness. Moreover, euphemistic terms for stigma could undermine the struggle to end mistreatment. If politically correct terminology sugar-coats social attitudes and behaviors, the public might not fully comprehend the egregious effects that stigma has for people with mental illness.

Furthermore, Steven Pinker (

13) has cautioned against the “euphemistic treadmill,” wherein words change while the essence of social understanding remains virtually stable. That is, the experience of stigma lasts beyond the change in labels. Examples of this exist in historical efforts to change mistreatment of racial and disability groups. Subtle discrimination against African Americans has persisted beyond the decline of widespread racial slurs, and leprosy is still stigmatized when called Hansen’s disease (

14).

Conclusions

We end with a cautionary note about language change. The mental health community is a diverse group with a multitude of preferences and perspectives (

14). Although resounding agreement among all is unlikely, the broad array of stakeholders, especially those with lived experience of mental illness, should be involved in decisions about language changes. If future investigation shows that the word “stigma” is harmful, then mental health advocates with lived experience should be the ones to identify a replacement, because when change in language is the endeavor of policy makers and researchers rather than those who live with mental illness, efforts risk alienating individuals most affected by these changes (

15).