The model.

Three full-time peer CTI specialists, a half-time clinical director, and a psychiatrist (.1 FTE) staffed the program. Peer specialists, who had experienced mental illness, substance abuse, or homelessness themselves, carried caseloads of approximately 15 clients. Clients were eligible to receive services for up to six months after leaving the psychiatric ER at Columbia University Medical Center, which in 2010 had approximately 4,500 visits annually.

CTI has two goals: to provide support and practical assistance during a transition and to strengthen individuals’ long-term ties to services and supports. Peer specialists met with clients in the community, using assertive outreach strategies to engage and develop relationships; identify reasons for repeated ER use; obtain ongoing mental health and substance abuse treatment, insurance, entitlements, housing, and vocational training; and facilitate reconnections with social supports.

Implementation.

Startup included hiring staff, obtaining stakeholder input, adapting the CTI manual for peer workers’ use with frequent ER users, building relationships with ER staff and community providers, and developing a resource guide. Adaptations included shortening the intervention from nine to six months to increase program capacity. Experienced peer staff were recruited without difficulty. They had significant work experience as case managers, substance abuse counselors, and outreach workers. They received CTI training and weekly clinical supervision. They had flexibility regarding when and whether to identify themselves as peers to clients and others.

Each month, program staff used ER data to update lists of frequent users (three or more ER visits in the prior year) (

6). Individuals with dementia or developmental disabilities or who lived outside New York City were excluded. If a Project Connect slot was available when an eligible individual arrived in the ER, a peer specialist approached the individual to describe the project and offer enrollment. Eligible individuals who entered the ER when none of the 45 slots were open received usual care. Enrollment occurred between February 2009 and April 2010. Project Connect enrolled 75 clients, of whom 55 provided informed consent to have their service use data reviewed; Medicaid claims data were available for 47. Because we could not examine data for nonconsenters, we could not determine differences with consenters.

Peer specialists advocated for high-quality discharge plans that addressed clients’ needs, helped problem solve before the first follow-up appointment, and assisted them when aftercare arrangements fell through. Peer specialists provided “safety nets,” working intensively with clients after discharge until stable plans were implemented. Peer specialists focused on facilitating engagement in psychiatric treatment, enhancing motivation for substance abuse treatment, facilitating access to medical care, finding housing, providing assistance in obtaining benefits, increasing family involvement, teaching self-management skills, encouraging return to work or school, and enhancing hope. Guiding principles included time-limited, flexible assertive outreach and engagement; recovery orientation; shared decision making; cultural competence; harm reduction; and motivational enhancement.

Evaluation.

According to supervisory staff and ER clinicians, peer specialists were well received by clients, engaged those who had been difficult to engage, and helped foster relationships between clients and community clinicians. Initially, some ER and inpatient staff were skeptical about working with peers; however, they quickly came to value peers’ contributions, sharing their feedback with program leadership.

Within three months of Project Connect admission, research staff approached clients to request informed consent for accessing their data. We used Medicaid claims data to compute the number of emergency visits, inpatient hospitalizations, and outpatient mental health services for each client before, during, and after the intervention and for a comparison group. For the comparison group, we identified Medicaid enrollees in the ER database who were otherwise eligible for Project Connect but who were not referred because of limited capacity, selecting 50 who entered the ER immediately after a Project Connect slot was filled. The NYS Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board granted a waiver of consent to review service use data from this group. Service use data were examined for three periods of Medicaid eligibility: six months before enrollment, six months after enrollment, and six months after completion. For the comparison group, we selected a comparable period six months before and 12 months after an index ER visit.

We analyzed claims data from 47 consenting participants and the 50-member comparison group using t tests and zero-inflated Poisson regression models. Participants (N=97) were mostly male (N=82, 85%), with mean age of 43±11 years. All were eligible for Medicaid on the basis of disability. Data on race-ethnicity and homelessness were available only for the 47 Project Connect participants. Thirty (63%) were homeless at entry, and most were non-Caucasian (Hispanic, N=20, 42%; African American, N=19, 41%; and other or mixed race, N=5, 11%). Although both groups were high users of behavioral health services in the six months before study entry, Project Connect participants had significantly more inpatient and emergency services days than the comparison group (p=.02). A larger proportion of Project Connect participants had a substance use disorder, but the difference was not significant (p=.07). These differences may be attributable to the fact that individuals who used the ER more frequently had more chances to arrive when a program slot was open.

Program participants had 1.45 times (95% confidence interval [CI]=1.02–2.07) the rate of use of emergency or inpatient services (general medical or behavioral health) than the control group during the six months after the index ER visit. Both groups reduced use of emergency and inpatient services .46 times (CI=.35–.61) per log-transformed month. For both groups, intensity of service use in the six months before the index ER visit significantly predicted subsequent service use, with higher use at baseline predicting slower rates of decrease.

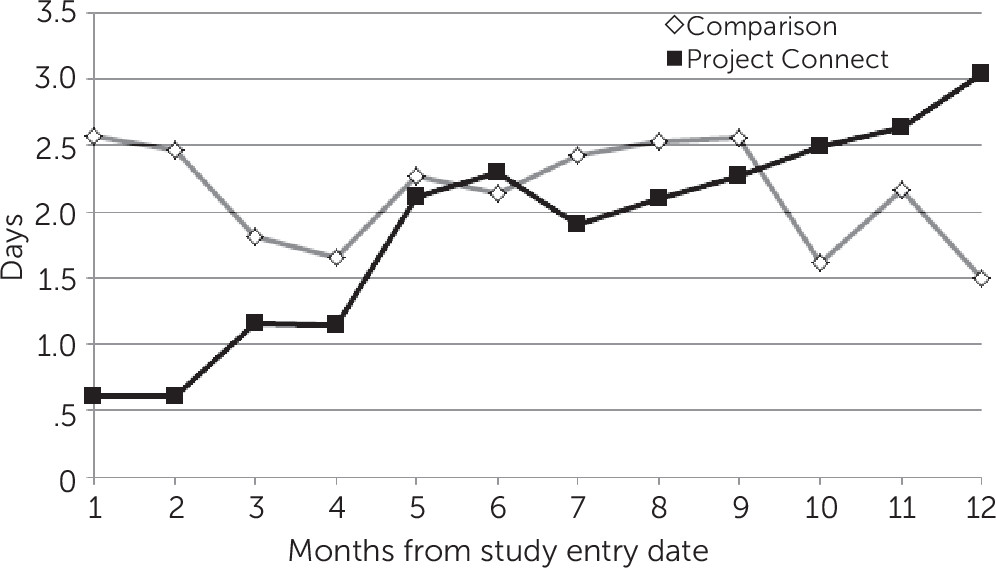

Figure 1 shows trends over time for outpatient service use, which increased for Project Connect participants from less than one day per month at study entry to about three days per month at 12 months. The increased use extended beyond the six-month intervention. For the comparison group, use of outpatient services decreased over the 12-month period. Across both groups, individuals with co-occurring substance use disorders engaged in outpatient services .64 times (CI=.48–.84) less than those without co-occurring disorders.