Systematic Review of Integrated General Medical and Psychiatric Self-Management Interventions for Adults With Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

Objective:

Methods:

Results:

Conclusions:

Methods

Search Strategy

Study Selection Criteria

Data Extraction

Methodological Quality Assessment

Potential for Implementation

Results

| Study | Design | Sample | Setting | Diagnosis | Intervention | Duration | Interventionist | Comparison | Measures | Main outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated telehealth | ||||||||||

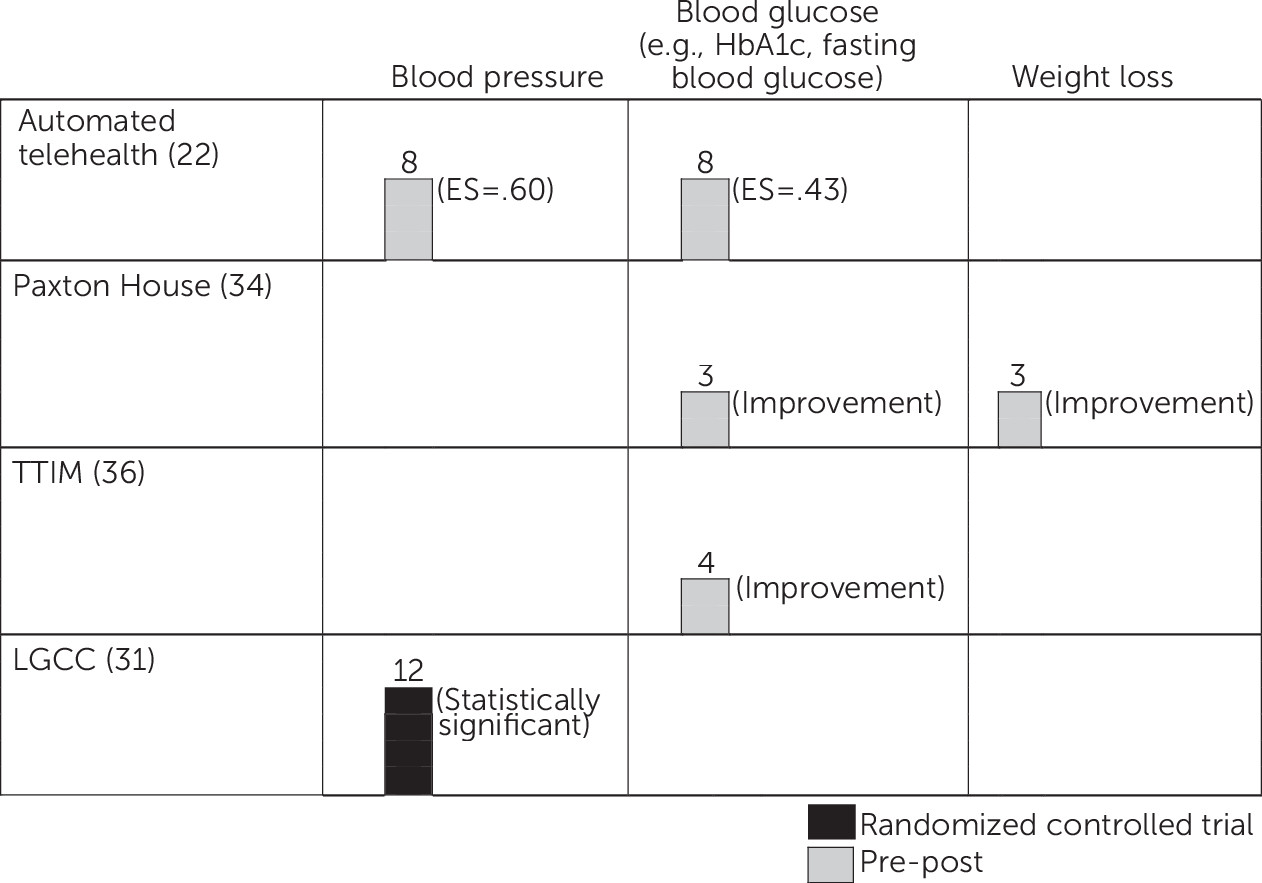

| Pratt et al., 2013 (22) | Pre-post | N=70 (54 female; 1 minority); mean age, 52.7±10.6 | Remote and home based | 12 bipolar disorder; 29 major depressive disorder; 18 PTSD; 11 schizophrenia; 7 COPD; 11 chronic pain; 6 congestive heart failure; 46 diabetes mellitus | A remote device that targets self-management of multiple psychiatric and general medical illnesses | 6 months of automated self-management behavioral prompts (e.g., “Have you taken your medication today?”), prompts to input biological indicators of health (e.g., blood glucose, weight), and psychiatric and general medical psychoeducation prompts | Remote technology in the consumer’s home supported by a nurse at a mental health center | na | Feasibility based on participant adherence; SCDSES, SF-12, BPRS, self-reported service use, health measures collected by the remote technology (BP, weight, and blood glucose) | Adherence over 70%; significant (p<.05) improvements at 6-month follow-up in depression self-management (SCDSES) (ES=–.33) and decrease in diastolic BP (ES=.60). Among those with diabetes, significant (p<.05) reductions in blood glucose (ES=.43), routine primary care visits (ES=.64), and urgent care visits (ES=1.11) |

| HARP | ||||||||||

| Druss et al., 2010 (23) | RCT | N=80 (41 HARP; 39 usual care; 56 female; 66 minority); mean age, 48.1±10.1 | CMHC | 26 bipolar disorder; 21 major depressive disorder; 9 PTSD; 23 schizophrenia; 39 arthritis; 18 asthma; 18 heart disease; 50 hypertension | Targets self-management (i.e., connection between mind and body, cross-systems medication coordination, psychiatric and general medical advance directives, healthy lifestyles, pain and fatigue management, finding and interacting with a doctor) | 6 group sessions; 6 months | 2 certified mental health peer specialists | Usual care (continuation of all general medical, mental health, and peer-based services prior to study entry) | PAM, BRFSS, health service use, self-reported medication adherence, SF-36 PCS and MCS | Significant (p<.05) improvement in patient activation (PAM) and use of primary care, compared with usual care |

| HOPES | ||||||||||

| Bartels et al., 2004 (26) | Controlled pilot | N=24; mean age, 66.5±5.7 | Assisted living facility | 4 bipolar disorder; 2 major depressive disorder; 2 psychotic disorder NOS; 3 schizoaffective disorder; 13 schizophrenia; (mean medical diagnoses, 4.3±2.7) | Enhanced Skills Training and Healthcare Management (STHM), later renamed HOPES (22) | 12 months of twice weekly group meetings and weekly nurse preventive health care visits | Rehabilitation specialist and psychiatric nurse | Health care management only (N=12) | ILSS, SBS, BPRS, SANS, GDS, MMSE | STHM resulted in significant (p<.05) improvements in care-of-possessions item (ILSS), compared with the control group, but not on the mean ILSS score. No between-group differences for other measures |

| Bartels et al., 2014 (24); Mueser et al., 2010 (25) | RCT | N=183 (90 HOPES; 93 treatment as usual); mean age, 60.2 | Mental health center or local senior center | 26 bipolar disorder; 44 major depressive disorder; 52 schizoaffective disorder; 51 schizophrenia; 25 asthma; 23 heart disease; 42 COPD; 50 diabetes; 80 hypertension; 32 hypothyroidism | Targets psychosocial rehabilitation and psychiatric and general medical self-management (i.e., social skills, illness self-management, medication management, communication with health care providers) | 12 months of weekly group meetings, two community trips per month to practice skills, and monthly preventive health care visits; during maintenance phase are monthly group skills training, community trips, and meetings with nurse | Groups co-led by a nurse and bachelor’s-level case manager; nurse preventive health care visits | Treatment as usual (usual mental health services, including pharmacotherapy, case management or outreach by nonnurses, individual therapy, and rehabilitation services, such as groups or psychoeducation | UPSA, MCAS, SBS, ILSS, RSES, SANS, cognitive functioning (D-KEFS, CVLT-II, card sorting test, Tower of London task, proverbs test, word context test, 20 questions test), BPRS, SF-36, CESD, CCI | Retention was high (80%). Compared with treatment as usual at 2-year follow-up, HOPES resulted in significant (p<.05) improvements in performance skills (UPSA), psychosocial and community functioning (MCAS), leisure and recreation (ILSS), negative symptoms (SANS), and self-efficacy (RSES). Results at 3-year follow-up showed significant (p<.05) improvements in community living skills (ILSS and MCAS), performance skills (UPSA), self-efficacy (RSES), and psychiatric symptoms (BPRS). At 3-year follow-up, significantly (p<.05) greater use of preventive health care, screening, and care planning with advance directives |

| I-IMR | ||||||||||

| Mueser, et al., 2012 (27) | Pre-post | N=7 (3 female); mean age, 59 | CMHC | 3 schizophrenia; 1 bipolar disorder; 3 major depressive disorder; 7 hypertension; 4 hyperlipidemia; 3 COPD; 2 osteoarthritis; 1 diabetes | Targets self-management of multiple psychiatric and general medical illnesses (i.e., individualized goal development, recovery strategies, connection between mind and body, psychoeducation, healthy lifestyles, managing stress, managing psychiatric and general medical health, medication management, and relapse prevention plans). | 8 months of weekly individual sessions | Master’s-level social worker supported by a nurse care manager | na | BPRS, IIMR scales, SRAHP | High participation in I-IMR (71% attended ≥10 sessions); some improvements among individual participants but no aggregate results reported |

| Bartels et al., 2014 (28) | RCT | N=71 (36 I-IMR; 35 usual care; 39 female; 2 minority); mean age, 60.3±6.5 | CMHC | 13 bipolar disorder; 31 major depressive disorder; 27 schizophrenia spectrum; 16 COPD; 34 diabetes; 33 hyperlipidemia; 29 hypertension; 46 osteoarthritis | See above (27) | 8 months of weekly individual sessions | Master’s level social worker supported by a nurse care manager | Usual care (included pharmacotherapy, case management or outreach by nonnurse clinicians, individual therapy, and access to psychosocial support and rehabilitation services) | I-IMR scales, SCDSES (SCDSES-adapted measures of diabetes, COPD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, arthritis self-management), BPRS, MCAS, SPCS, API, self-reported hospitalizations and emergency visits | Compared with usual care, I-IMR resulted in significant improvements (I-IMR scales) in psychiatric (ES=.46) and general medical (ES=.29) illness self-management and significant improvements (SCDSES) in diabetes self-management skills (ES=.15). During primary care visits, there was an increase (API subscale) in preference for comprehensive diagnosis and treatment information (ES=.88) and decreases in self-reported psychiatric or medical hospitalizations (p=.037). |

| LGCC | ||||||||||

| Kilbourne et al., 2008 (29) | RCT | N=58 (all veterans; 27 BCM; 31 usual care; 5 female; 6 minority); mean age, 55.3±8.4 | Veterans Affairs outpatient mental health facility | 44 bipolar disorder I; 4 bipolar disorder II; 10 bipolar disorder NOS; 19 diabetes; 52 obesity; 47 hypertension; 44 hyperlipidemia; 11 coronary artery disease; 10 COPD; 4 chronic hepatitis; 19 osteoarthritis | BCM, later renamed LGCC (30) | 4 2-hour group sessions followed by 6 months of monthly telephone care management services | Care management by a nurse; groups led by a nurse manager | Usual care | SF-12, WHO-DAS, ISS, LSMECD, CAS, current medication use, number of outpatient general medical visits | Compared with usual care, BCM resulted in significant (p<.05) improvements in physical health–related quality of life (SF-12 PCS). |

| Kilbourne et al., 2012 (30) | RCT | N=65 (32 LGCC; 33 usual care; 39 female; 12 minority); mean age, 45.3±12.8 | Community-based mental health outpatient clinic | 65 bipolar disorder; 35.2±7.3 BMI; 45.0±6.0 inches waist circumference; 133.9±1.7 mmHg systolic BP; 85.1±11.1 mmHg diastolic BP | Targets self-management of bipolar spectrum disorder and risk factors for cardiovascular disease (i.e., individualized goal development, healthy behavioral change, and action plans to cope with symptoms); care management, and self-management practice guidelines are given to providers | 4 2-hour group sessions followed by 6 months of telephone care management services | Master’s-level social worker | Enhanced treatment as usual (included monthly receipt of mailings on wellness topics over the 6-month LGCC intervention period, in addition to available mental health care and referral to primary care services off site | Cardiometabolic risk (BMI, systolic/diastolic BP), SF-12; WHO-DAS, ISS | Only for consumers with BMI ≥30, compared with usual care, LGCC resulted in a significant decrease in impaired functioning (WHO-DAS) (β=–2.2) and depressive symptoms (ISS) (β=–2.0). Among those with systolic BP ≥140, LGCC resulted in a significant decrease in impaired functioning (WHO-DAS) (β=–3.8) and depressive symptoms (ISS) (β=–3.5). |

| Kilbourne al., 2013 (31) | RCT | N=118 (all veterans; 60 LGCC; 58 usual care; 20 female; 6 minority; mean age, 52.8±9.9 | Outpatient mental health or primary care clinic | 44 bipolar disorder I; 26 bipolar disorder II; 45 bipolar disorder; 3 schizoaffective bipolar disorder subtype; 30 diabetes mellitus; 22 heart disease; 98 hyperlipidemia; 81 hypertension; 58 obesity | See above (30) | 4 2-hour group sessions followed by 6 months of telephone care management services | Master’s-level health specialist | Enhanced usual care (regular mailings on wellness topics, in addition to standard mental health and general medical treatment; standard treatment included outpatient case management and group psychotherapy sessions specifically focused on mental health treatment and provided by a mental health team, as well as access to a primary care provider) | Systolic/diastolic BP, cholesterol, SF-12, WHO-DAS, ISS | Compared with usual care, LGCC resulted in a significant (p<.05) reduction in systolic (β=–3.1) and diastolic BP (β=–2.1) and fewer manic symptoms (ISS) (β=–23.9). |

| Living Well | ||||||||||

| Goldberg et al., 2013 (32) | RCT | N=63 (32 Living Well; 31 usual care; 33 female; 42 minority); mean age, 49.5±9.1 | Outpatient clinic and psychiatric rehabilitation day program | All bipolar disorder with psychotic features or schizophrenia spectrum disorder; 27 arthritis; 17 cardiovascular disease; 31 diabetes; 25 respiratory disease | Targets psychiatric and general medical illness self-management (i.e., healthy lifestyles, medication management, addictive behaviors, and cross-system coordination of services); adapted from the CDSMP and focuses on confidence building to develop self-management skills, with additional material on how serious mental illness affects general medical status and vice versa | 13 weekly group sessions and weekly follow-up telephone calls | Groups co-led by a mental health peer and a mental health provider or by 2 mental health peers who also have a chronic general medical condition; follow-up telephone calls by peers | Usual care | SF-12, SMSES, PAS, MHLC, RAS-SF, IMSM, MMAS | Compared with usual care, between baseline and 13 weeks, Living Well resulted in significant (p<.05) improvements as follows: in physical functioning (ES=.55), emotional well-being (ES=.66), and general health functioning (ES=.68) (SF–12 MCS and PCS); in self-management self-efficacy (ES=.65) (SMSES); in patient activation (ES=.55) and approach to health care (ES=.61) (PAS); and in self-management behaviors (ES=.57) and use of health care (ES=.81) (IMSM). Only improvement in use of health care remained significant at 2-month follow-up (ES=.54) (IMSM). At 2-month follow-up, significant improvements in internal locus of control (ES=.66) (MHLC) and in physical activity (ES=.56) and healthy eating (ES=.64) (IMSM) |

| Norlunga program | ||||||||||

| Lawn et al., 2007 (33) | Pre-post | N=38 (35 Flinders care planning; 17 Stanford groups; 3 Stanford groups only; 21 female); males’mean age, 39; females’ mean age, 46 | Primary care | 4 anxiety disorder; 5 bipolar disorder; 8 major depressive disorder; 1 personality disorder; 4 schizoaffective disorder; 16 schizophrenia; 22 with ≥2 conditions; most common conditions: obesity, asthma and other respiratory conditions, heart disease, and diabetes | Targets psychiatric and general medical self-management through education and peer support | 12 months of a hybrid individual and group approach | Peer educators | na | PIH, P&G, WSAS, SF-12 | Norlunga program resulted in significant (p<.05) improvements at 3 and 6 months in self-management (PIH) and mental functioning (SF-12 MCS), in social leisure activities (WSAS), and in reduced problem impact (P&G). Qualitative feedback was supportive of the intervention. |

| Paxton House | ||||||||||

| Teachout et al., 2011 (34) | Pre-post | N=13 (4 female; 9 minority); mean age, 45.0±6.9 | Supported housing residence | 2 major depressive disorder; 1 psychotic disorder NOS; 6 schizophrenia; 4 schizoaffective disorder; all with type II diabetes | Offers psychosocial rehabilitation and diabetes self-management services (i.e., diabetes education and nutritional programs), psychiatric support, intensive case management, and residential support | 6 months of individual and group sessions | Advanced-practice nurses and clinical staff | na | Weekly weight; daily blood glucose, satisfaction survey, DES-SF | At 6-month follow-up, Paxton House resulted in weight loss for all participants (mean=20.35 pounds), improved fasting glucose for 40%, and overall satisfaction with the program. |

| TTIM | ||||||||||

| Blixen et al, 2011 (35); Sajatovic et al., 2011 (36) | Pre-post | N=12; age range, 33–62; median age, 49.5 | Primary care | Bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder; all with diabetes | Targets psychiatric and diabetes self-management | 12 weekly 60- to 90-minute group sessions and 4-week maintenance period consisting of weekly telephone sessions | Groups co-led by peer educator with serious mental illness and diabetes and nurse educator | na | BPRS, MADRS, CGI, GAF, SDS, HbA1c, BMI; SF-12, SDSCA | TTIM qualitative findings suggest increased illness knowledge, self-confidence, and motivation. Quantitative findings suggest increased self-management of serious mental illness and diabetes, such as reduction in psychiatric symptom severity (BPRS) and improvement in perceived mental and physical health status (SF-12 MCS and PCS). For 8 participants, improvement in HbA1c was noted. Significant (p<.05) improvement in dietary behaviors for diabetes self-management (SDSCA) |

Evidence of Intervention Feasibility, Acceptability, and Effectiveness

Methodological Quality Assessment

| Attribute (range of possible scores) | Sajatovic et al. (36); Blixen et al. (35) | Druss et al. (23) | Bartels et al. (26) | Goldberg et al. (32) | Mueser et al. (25); Bartels et al. (24) | Kilbourne et al. (29) | Kilbourne et al. (30) | Kilbourne et al. (31) | Lawn et al. (33) | Teachout et al. (34) | Mueser et al. (27) | Bartels et al. (28) | Pratt al. (22) et al. (22) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design (0–4) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Replicability (0–1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Baseline (0–1) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Quality control (0–1) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Follow-up length (0–2) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Follow-up rate (0–2) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Objective measurement of outcomes (0–1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Dropouts (0–1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Independent (0–1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Analyses (0–1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Study site (0–1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Collateral (0–1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total score | 4 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 12 | 8 |

Potential for Implementation

Discussion

Conclusions

Footnote

Supplementary Material

- View/Download

- 55.52 KB

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

Cover: covered jar with star decoration, by Solomon Grimm, 1822. Glazed red earthenware. Gift of Ralph Esmerian. American Folk Art Museum, New York City. Photo: John Begelow Taylor; American Folk Art Musuem/Art Resource, New York City.

History

Authors

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing PsychiatryOnline@psych.org or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).