Adverse birth events are more common among women who have depression during pregnancy (

1). Antenatal depressive symptoms increase the relative risk of preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation) by 39%, low birth weight (LBW) (<2,500 g) by 49%, and intrauterine growth retardation (below the tenth percentile for gestational age) by 45% (

2). This risk is higher among women of lower socioeconomic class (

2). Elevated depression scores at 32 weeks’ gestation (

3) and major depression diagnosed at any time during pregnancy (

4) are also related to adverse birth events, with greater duration of antenatal depression associated with higher odds of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (

5–

7). Not only are adverse birth events more common among women with antenatal depression, but obstetric complications and adverse birth events are also associated with rates of postpartum depressive symptoms as high as 40% (

8). Mothers with LBW babies continue to be at increased risk of depression at one year postpartum (

9). For mothers with low socioeconomic status this period of risk extends to two years (

10).

According to the stress-diathesis model (

11), for a person with predisposing factors for depression (family history or past history), experiencing a significant stressor is more likely to lead to a depressive episode, compared with a person without this predisposition (

12,

13). Antenatal depression is one of the strongest predisposing factors for postpartum depression, even after normal full-term deliveries (

14,

15). Adverse birth events constitute a significant and stressful life event (

16). Thus having an adverse birth event could increase the risk of postpartum depression (

6) among women with antenatal depression.

Infants who experienced adverse birth events, such as prematurity or LBW, are at high risk of long-term negative outcomes, such as lower educational achievement and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (

17), anxiety disorders, and autism spectrum disorder (

18). In addition to prematurity, environmental factors, such as parental psychological distress, contribute to this set of risks for the infant. Mothers who have depression can be less responsive and less sensitively attuned to their infants (

19). Of note, maternal responsivity moderates the effects of LBW on hyperkinetic and internalizing behaviors among LBW babies (

20,

21). In other words, maternal postpartum depression, by reducing maternal responsivity, can magnify the risk of poor outcomes for preterm or LBW infants.

Thus any effort to prevent poor infant outcomes is incomplete without attention to maternal psychological distress, especially because maternal depression has been shown to mediate the remoteness seen in parenting interactions between mothers and their preterm babies (

21). To that end, various interventions to reduce mothers’ psychological distress after adverse birth events have been tested, including educational-behavioral programs (

22), anxiety reduction (

23), and sensitivity training (

24). These programs have components of child development or parenting support; however, none addresses maternal depression specifically. Overall, although studies reported decreased stress (

22,

24) and increased rates of breastfeeding (

25), most studies found no improvement in maternal depression (

22–

24).

With the exception of a single study (

26), research has not addressed the population of women who were depressed during pregnancy and who experienced adverse birth events and, therefore, were at higher risk of postpartum depression (

27). Postpartum support can improve maternal mental health in high-risk populations (

28), and parents’ coping after an adverse birth event has been reported to be influenced by the availability of social support (

29). The literature suggests that general social support and parenting support may reduce risk of postpartum depression among mothers without antenatal depression who experience adverse birth events (

22,

30). However, mothers who have had antenatal depression and also experience adverse birth events may require more specialized support to reduce depression during the perinatal period (

26).

We recently reported that the MOMCare collaborative care intervention for perinatal depression was more effective on average in reducing depression severity and increasing remission rates from pregnancy to 15 months postpartum than a comparison condition of intensive public health maternity support services (MSS-Plus) (

31). The purpose of the analysis reported here was to determine to what extent MOMCare, compared with MSS-Plus, reduced postpartum depression severity for mothers who experienced one or more adverse birth events. That is, for the study sample of women who had antenatal depression, to what extent did the intervention moderate the negative effect of experiencing an adverse birth event on postpartum depression severity?

We hypothesized that despite having an adverse birth event, women with antenatal depression would have less postpartum depression severity if they received the MOMCare intervention rather than MSS-Plus. We also hypothesized that despite experiencing an adverse birth event, mothers in the MOMCare intervention would have better functioning in the postpartum period compared with mothers in MSS-Plus.

Methods

In a multisite randomized controlled trial with blinded assignment, we evaluated the MOMCare collaborative care intervention for perinatal depression compared with MSS-Plus in ten Seattle–King County public health centers from July 2009 to January 2011. Participants were recruited who met criteria for a probable major depressive disorder on the basis of the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (

32) (at least five symptoms scored as ≥2, with one cardinal symptom; and functional impairment noted on the PHQ-9) or a probable diagnosis of dysthymia on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (

33). Study procedures were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board and monitored by a Data Safety Monitoring Board. All participants signed study consent and HIPAA release forms, allowing the project to request their hospital labor, delivery, and birth information; 98% of hospital records were obtained.

Participants

The original study sample included 168 Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women; 83 were randomly assigned to the MOMCare intervention and 85 to the MSS-Plus comparison group. Randomization was by an adaptive block scheme, stratified on initial depression severity via the 20-item Symptom Checklist (SCL-20) (

34) (≤2.0 or >2.0) and gestational age (<22 weeks or ≥22 weeks). The analyses reported here included 160 women; it excluded those for whom hospitals failed to provide medical records (N=4) and those who dropped out of the study prior to the baseline interview (N=4).

MSS-Plus

Maternity support services (MSS) is the usual standard of care in the public health system of Seattle–King County for Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women, delivered by a multidisciplinary team of public health social workers, nurses, and nutritionists, who screen at least once for depression from pregnancy to two months postpartum. Goals of usual MSS include services to promote healthy pregnancies and positive birth and parenting outcomes, case management services, and facilitating contact with an obstetric provider. Pregnant women with PHQ-9 scores ≥10 were eligible for intensive MSS-Plus services, entailing more frequent and longer visits from their multidisciplinary team from pregnancy to two months postpartum. MSS-Plus providers referred depressed patients for mental health treatment in the community or from their obstetric providers. The MSS-Plus providers did not provide evidence-based depression care, systematic outreach, or stepped care.

MOMCare

The MOMCare intervention was added onto MSS-Plus and extended from pregnancy to 12 months postpartum (

35). MOMCare was delivered by depression care specialists (DCSs) in consultation with the principal investigator (NKG) and the study psychiatrist (WK). The DCSs collaborated with their patients’ obstetric providers, providing updates on progress, and collaborating on medication management if indicated. Intervention services were provided in the public health centers, by phone, in community settings, and at home. The DCSs specifically provided depression care management, and the MSS-Plus providers did not (

Table 1).

MOMCare was designed to decrease mental health treatment disparities in access to and quality of care (

35). Novel components include a pretherapy engagement session to help resolve practical, psychological, and cultural barriers to care; patient choice of brief interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), pharmacotherapy, or both; telephone sessions in addition to in-person visits; outreach for women who miss sessions; and DCSs who deliver both the intervention and case management to meet basic needs (

35).

Measures

The primary outcome measure was the SCL-20, a reliable and valid measure of depression (

34). It is sensitive to change (

36) and has good internal consistency (

37) and good convergent validity with the items on the PHQ-9 (

38). Scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. The mean score was used to measure overall depression severity and to calculate depression treatment response (≥50% reduction from baseline depression severity) and remission (SCL-20 score <.5).

Functional impairment was assessed by the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) (

39), a five-item, self-report scale that measures functional impairment attributable to an identified problem. It is reliable and valid and has high correlation with clinician reports. Questions were asked in reference to “emotional difficulties.”

The Peripartum Events Scale (PES) (

40) has established reliability and validity and is used to quantify labor, delivery, and birth outcome events obtained from hospital records. Two coders (one primary coder [HJ] and one reliability coder [CER]) were trained by the project’s obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) consultant physician. The primary coder had a doctoral degree in social work, and the reliability coder was a resident OB/GYN physician. The first ten cases were coded by both coders to establish reliability. Subsequently, 20% of the medical records were coded by both coders, and interrater reliability averaged 99% agreement. The project’s OB/GYN consultant physician (JLM) and a resident physician provided assistance in coding when needed. The PES produces 11 subscales assessing a variety of stressful events associated with childbearing. For the purpose of this analysis, we defined an adverse neonatal birth event as any event endorsed on the PES infant outcome subscale (ten items) or whether the infant was placed in the NICU or special care nursery.

The Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist–Civilian Version is a 17-item questionnaire that assesses intrusive symptoms, avoidance, and arousal associated with traumatic events (

41). A continuous PTSD severity score was calculated.

Statistical Analyses

We first calculated descriptive statistics for the entire sample. Because previous analyses showed significantly reduced depression severity for mothers in the MOMCare intervention compared with those in MSS-Plus (

31), we tested postpartum depression symptom levels between women with and without an adverse birth event within each intervention arm separately. Because the adverse birth event groups were not based on randomization, we examined baseline differences between variables, including obstetric complications, parity (number of births after gestational age 20 weeks), and social support in these groups within each intervention arm by using chi-square analyses and t tests. We found no differences, and the variables were not utilized as adjustments in our models. However, because baseline PTSD symptom severity was found to have a substantial impact on depression symptom levels in our initial primary outcome analyses (

31), we included it in our models.

We used generalized estimating equations (GEEs) to estimate differences in depression measures and functioning between women with and without adverse birth events within the treatment arm cohorts. The GEE longitudinal model allowed inclusion of all women, including those with missing assessments. All GEE models were fitted with robust error estimation and an unstructured covariance matrix. The dependent variables were SCL-20 depression severity and response and remission at six, 12, and 18 months postbaseline (that is, postpartum depression for a year after birth). Each model contained main effects for adverse birth event and time, adjusted for baseline depression severity and PTSD severity level. For the analysis of functioning, baseline WSAS level was used in the model in lieu of baseline depression. Means and standard errors were estimated from the GEE models.

Results

There were 160 women in the analysis sample; 68 (43%) had one or more adverse birth events and 92 (58%) had no adverse event. Data on baseline demographic variables are presented in

Table 2. There was no association between having an adverse birth event and treatment group; 47% (N=37) of the MSS-Plus group experienced an adverse birth event, compared with 40% (N=32) of the MOMCare group. Within the MSS-Plus and MOMCare groups, all baseline variables between those with and without an eventual adverse birth event were similar. Frequencies of events considered to be adverse are presented in

Table 3.

Adverse Birth Events and Postpartum Depression Severity

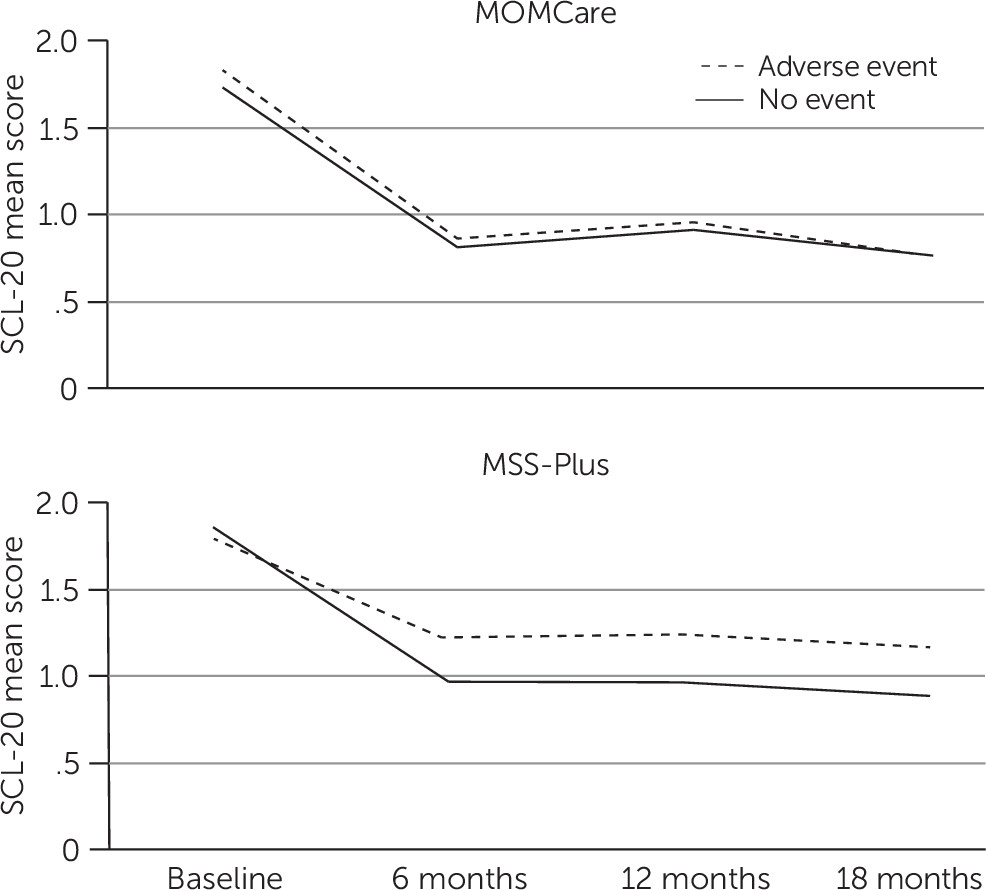

Time was not a significant main effect or interaction in any of the models (

Figure 1). In the MOMCare group, the model for continuous SCL-20 depression severity scores indicated a nonsignificant main effect of adverse birth outcome. The average depression score (average of scores at six, 12, and 18 months postbaseline) was .86 for the mothers with an adverse birth event, compared with .83 for those with no adverse birth event (

Table 4). In contrast, in the MSS-Plus group, there was a significant main effect of adverse birth event (Wald χ

2=4.16, df=1, p=.04), with average depression severity scores of 1.20 for mothers with an adverse birth event, compared with .93 for those without an adverse birth event.

Depression response results (≥50% reduction from baseline severity) were similar for MOMCare; the model showed a nonsignificant main effect of adverse birth event. The average depression response (average at six, 12, and 18 months postbaseline) was 51% for mothers with an adverse birth event, compared with 55% for those without an adverse birth event (

Table 4). In contrast, in the MSS-Plus group, there was a significant main effect of birth event (Wald χ

2=4.04, df=1, p=.04), with an average depression response of 36% for the mothers with an adverse birth event, compared with 55% for mothers without an adverse event. Remission from depression (SCL-20 score <.5) was not significantly different between those with and without adverse events for either MOMCare or MSS-Plus.

Adverse Birth Events and Postpartum Functioning

In the MOMCare cohort, the mothers with and without adverse birth events did not differ on WSAS functioning scores (

Table 4). However, in the MSS-Plus group, those with an adverse birth event reported significantly more impairment (Wald χ

2=4.29, df=1,p=.04). The mean WSAS score was 15.22 for MSS-Plus group mothers with an adverse birth event, compared with 11.65 for those without an adverse birth event.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we examined the effectiveness of collaborative care for perinatal depression among mothers with antenatal depression who were enrolled in Medicaid and who experienced an adverse birth event such as preterm delivery, intrauterine growth retardation, “small for gestational age,” low Apgar score, or admission of the infant to a progressive care nursery or NICU. To our knowledge, this is the first study testing the effectiveness of an intervention in reducing postpartum depression among women with antenatal depression and low incomes who have experienced an adverse birth event.

The rate of adverse birth events of 43% in our sample is comparable to previous reports of 46% in other pregnant populations (

26). Corresponding to the stress-diathesis hypothesis, women with antenatal depression (

42) and women of low socioeconomic status (

43) are vulnerable to postpartum depression. For these women, the stress of events, including premature birth and infant illness (

44), can increase the risk of postpartum depression. Our intervention, the patient’s choice of IPT, pharmacotherapy, or both, appears to have mitigated the risk of worsening maternal postpartum depression severity and impaired functioning associated with adverse birth events (

45).

For mothers who received the MOMCare intervention, postpartum depression scores and functioning did not differ among those who did or did not experience an adverse birth event. By contrast, for women who received the MSS-Plus comparison condition, having an adverse birth event was associated with persistent distress in the postpartum period. That is, without the additional, longer-lasting support of MOMCare, those in MSS-Plus fared worse in terms of postpartum depression severity and impaired functioning after an adverse birth event.

Adverse birth events such as preterm labor have also been associated with a perception of the child as vulnerable to medical illness—more so in women of lower socioeconomic status (

46). Both postpartum depression and perceived child vulnerability can lead to disturbance of the mother-child interaction (

47) and contribute to an increased risk of behavioral and emotional disorders’ persisting into adolescence (

48). Thus interventions such as MOMCare that reduce risk of maternal postpartum depression severity after adverse birth events can have especially far-reaching benefits for high-risk mother-baby dyads.

A strength of the study was that it was conducted in a sample of socioeconomically disadvantaged women, a population at higher risk of both postpartum depression and adverse birth events. We have previously reported on the effectiveness of MOMCare in reducing depression among women of lower socioeconomic status with perinatal depression (

31), and we also reported that for women with comorbid depression and PTSD, MOMCare performed better than MSS-Plus in terms of depression severity improvement (

49). The analysis reported here adds to these findings, in finding that for mothers with the vulnerability of low socioeconomic status, antenatal depression, and at least one adverse birth event, receipt of the MOMCare intervention prevented continuing postpartum depression. We did not find a reduction in adverse birth events among women who received MOMCare; however, randomization was not based on risk of adverse birth events, and thus the study was not designed or powered to examine this question.

Randomization was not based on adverse events, which was a limitation. However, on comparison of multiple variables, the two groups (mothers with and without adverse birth events) were strikingly similar. Reports of psychiatric outcomes are limited to probable major depression and dysthymia and were based on rating scales and not diagnostic assessments. However, in the perinatal period, even subsyndromal symptoms of anxiety and depression can have implications for mother and child and are no less important than diagnoses (

50,

51). The PES does not specifically include the adverse event of LBW, which is an important outcome among women with perinatal depression. However, it does include “small for gestational age,” which factors in LBW. Although improvement in child outcomes is increasingly emphasized as a paired index of successful treatment of maternal depression, we did not have objective measures for this.

The United States continues to have high rates of adverse birth events, such as preterm birth (9.7% in 2014) and LBW (8% in 2014), with the highest rates found among women from racial-ethnic minority groups and women of low socioeconomic status (

52). Given that low socioeconomic status and adverse birth events contribute to accumulation of risk for postpartum depressive symptoms, there is a compelling need to implement stepped care interventions, such as MOMCare, that are effective for socioeconomically disadvantaged women and other high-risk groups. IPT is effective in the treatment of postpartum depression (

53), and as we report, it was effective in mitigating the risk of postpartum depressive severity after adverse birth events. In other words, for women with antenatal depression, MOMCare can reduce the risk of persistence of depression in the postpartum period despite the additional risk of an adverse birth event.

Providers caring for mothers with complicated deliveries and adverse birth events, for preterm LBW neonates, or for pregnant and postpartum women with mental health conditions are all well placed to identify persistent depression in the postpartum period. It is important for them to be aware of available effective interventions, such as MOMCare, that can be implemented in the context of caring for vulnerable infants.