Factors predicting violent assaults on staff by patients in psychiatric inpatient settings are poorly understood. Some studies suggest that the risk of committing assaults is increased among patients with certain diagnoses, such as schizophrenia (

1,

2), affective disorder (

3), and impulse control disorder (

4). Other patient characteristics, such as being male (

2), having a history of violence (

3,

5) or substance abuse (

2,

3), having sleeping problems (

6) or having poor self-reflective skills (

5), have also been associated with assaults.

However, patient characteristics may explain only a proportion of violent assaults (

7). Other factors may increase the risk of being subjected to violent assaults, such as shift work (

8,

9) and a fixed schedule of night work (

10), poor information flow among coworkers (

8), patient overcrowding (

11), and uncertainty among nurses regarding treatment (

9). Nurses’ characteristics, such as being male (

8,

9), being young (

8,

9,

12), having a lower level of qualifications (

9,

12), or having less training (

12) or work experience (

12,

13), may also be associated with an increased risk of being subjected to assaults. One qualitative study reported that when nurses feel pressured at work, distractions or miscommunications between patients and staff may arise, which may result in patient assaults (

14). This observation supports earlier findings that have associated high job strain, psychological distress (

15), job demands (

16), time pressure at work (

9), and problems in staff-patient interaction (

17,

18) with patient assaults. Likewise, workplace support (

15), interpersonal relationships between staff (

8), quality of teamwork (

9), and organizational justice (

15) may play a role in patient assaults.

Justice refers to an action or decision that is understood to be morally right on the basis of ethics, religion, fairness, equity, or law (

19). Organizational justice, originally derived from equity theory (

20), refers to an employee’s perception of his or her organization’s behaviors, decisions, and actions and how these influence the employee’s own attitudes and behaviors at work (

21). Previous research has shown that low organizational justice causes increases in employees’ stress levels (

22,

23), intragroup conflicts (

24) and work group misbehavior (

25). Poor teamwork creates inadequate program organization, which results in higher levels of stress among nurses (

26) and may cause additional assaults on psychiatric wards (

7,

27).

Despite inconsistency in the literature about the causes of patient violence, the topic has attracted constant attention from researchers (

8,

28). It has been suggested as one of the main reasons for decreased commitment (

8,

9) to an organization among staff, for the intention of leaving the profession (

9,

29), as well as for accidents, disability, death, absenteeism (

29), negative feelings (

30), lower job satisfaction (

29) and burnout (

9) among staff members. Given that patient violence toward nurses in psychiatric settings is a complex and multidimensional problem (

7), there is an urgent need to identify the factors contributing to its prevalence.

In this cross-sectional survey study, we developed a hypothesis that extended the ideas from existing research on the interaction of organizational justice, collaboration between nurses, nurses’ stress, and patient violence. On the basis of this hypothesis, we formulated and tested a model using the following assumptions. First, the perception of low organizational justice by nurses is associated with increased stress, which in turn is associated with an increased number of violent assaults by patients. Second, low organizational justice is associated with poor collaboration among nurses. Third, poor collaboration among nurses is associated with increased stress, which in turn is associated with increased numbers of violent assaults by patients.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants were selected from the Finnish Public Sector (FPS) study cohort, which includes employees in ten towns and six hospital districts. Employers' records are used to identify eligible employees for nested survey cohorts that have been sent questionnaires by mail or e-mail every four years since 2000. For our study, we used a subset of FPS cross-sectional questionnaire data collected in 2012 from five of the nation’s 20 hospital districts and one regional hospital providing specialized psychiatric care. Eligible participants were nurses (registered nurses and licensed practical nurses) working on the 90 psychiatric inpatient wards operational at the time of the survey (N=1,033). Of these, 758 (73%) responded to the survey in Finnish measuring psychosocial work environment and patient assaults, which was part of the FPS questionnaire survey exploring behavioral and psychosocial factors and health. The Ethics Committee of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District approved the study. The principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

Measures

The occurrence of violent assaults by patients was surveyed retrospectively with a measure developed for the purposes of the FPS study (

11). Respondents are asked whether they had encountered any of the four listed types of violent incidents at work (verbal threats; physical violence, such as hitting or kicking; assaults on ward property, such as throwing objects; and armed threats during the past year (yes=1, no=0). Respondents also indicated the month in which the exposure occurred, from 1, January, to 12, December. The occurrence of violent assaults by patients was combined into a sum score by calculating the number of months in which any of the four types of violence had occurred during the past 12 months (range 0–48). In this study, the internal consistency of the scale was respectable (.77), as measured by the Kuder-Richardson formula.

Organizational justice was measured by using a questionnaire of procedural and relational justice adopted from Moorman’s organizational justice measure (

31,

32). Procedural justice refers to the extent that decision-making procedures include input from all parties affected, are consistently applied, are accurate, suppress bias, and are correctable and ethical. Relational justice refers to considerate, polite, and fair treatment of individuals (

33). The questionnaire measures respondents’ current opinions on procedural justice (seven items) and relational justice (six items) at their organization on a 5-point scale, from 1, totally disagree, to 5, totally agree, with higher scores indicating better organizational justice. A mean scale score was calculated for both scales by averaging the scores on each item. The instrument has been used with Finnish health care staff (

34), and its internal consistency has been strong (procedural justice, α=.90 [

32], α=.80 [

35]; relational justice, α=.81 [

32], α=.90 [

35]). In our data, the internal consistency of the scales remained strong (procedural justice, α=.94; relational justice, α=.91).

Collaboration was measured by using two subscales derived from the 14-item Team Climate Inventory (TCI) (

36,

37). Participative safety, with four items, measures the extent to which “involvement in decision-making is motivated and reinforced while occurring in an environment which is perceived as interpersonally nonthreatening.” Support for innovation, with three items, refers to the “expectation, approval, and practical support of attempts to introduce new and improved ways of doing things in the work environment” (

38). Items are rated from 1, totally disagree, to 5, totally agree, with higher scores indicating better collaboration. A mean scale score was calculated by averaging the scores on each item. The subscales have been used with Finnish health care staff (

39). The internal consistency of the subscales has been strong in earlier studies (participative safety, α=.87; support for innovation, α=.81 [

40]) and remained strong in our data (participative safety, α=.86, support for innovation, α=.82).

Nurses’ psychological distress, or stress, was measured with the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), which measures minor psychiatric morbidity (

41). Respondents rate the extent to which they have experienced the symptoms of distress in the past few weeks, from 0, not at all, to 3, much more than usual, with higher scores indicating greater stress. A mean scale score was calculated by averaging the scores on each item.

The scale has previously been used as an indicator of stress (

42–

45). The GHQ-12 has been used with Finnish health care staff (

46) and has been validated in the Finnish population (

47). The internal consistency of the scale has been strong (α=.90 [

48], α=.85 [

49]), and it remained strong in our data (α=.88).

All instruments (organizational justice scale, the TCI, and the GHQ-12), which were originally written in English, had been translated to Finnish before this study.

Data Analysis

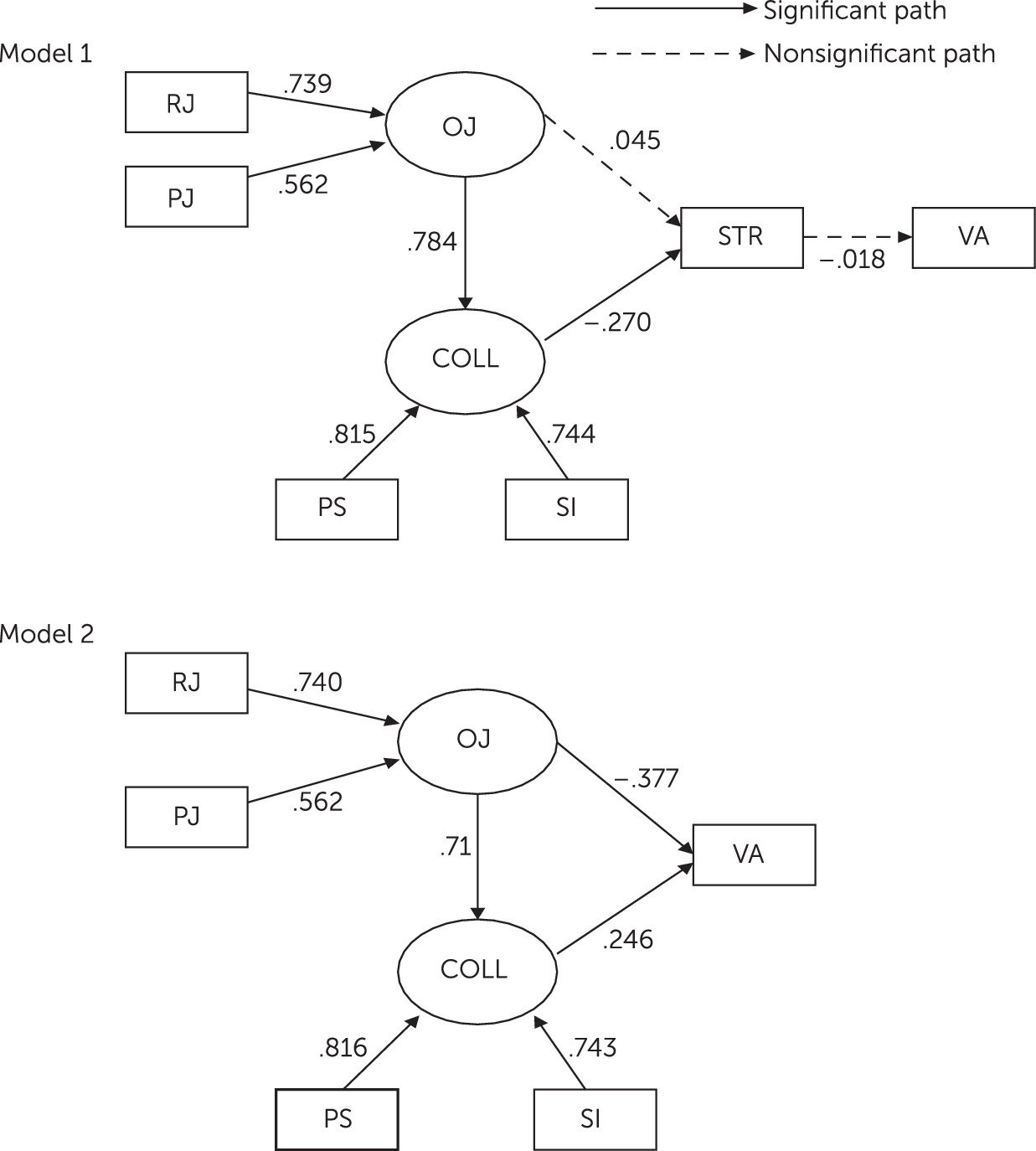

Our proposed model consisted of organizational justice, collaboration among nurses, stress, and patient violent assaults. The model construction is described in model 1 of

Figure 1. Stress was considered as a mediator between the two factors (organizational justice and collaboration) and violent assaults by patients. The model was encoded into a multiple regression equation by arrows indicating the relationships between specific factors. The fit of the model was determined by using structural equation modeling (SEM) with maximum likelihood estimations to test the hypothesized model. SEM was chosen because it is suitable for confirmatory testing of hypothesized models that are supported by either theories or empirical research. Criteria for goodness of fit of the model included nonsignificant chi-square statistics as well as findings for the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). The chi-square test is an absolute test of model fit, so the model is rejected in case of p<.05. CFI values may range between 0 and 1, with values close to 1 indicating very good fit (

50); in this study the CFI was set at >.95. Further, a TLI index close to 1.0 and RMSEA values <.05 were set as criteria for a fit model (

51). SRMR, the most sensitive index for detecting misspecified latent structures or factor covariances, was set at ≤.08 (

51). The model’s ability to explain assaults was assessed by using the coefficient of determination (R

2) (

52). Mplus was used for the SEM, and SPSS, version 21, was used for the other analyses.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics

The majority of participants were female (74%) registered nurses (58%) who worked full-time (95%) on a permanent employment contract (78%). The majority had been exposed to verbal threats (59%, N=424) during the past year; 46% (N=338) reported assaults on ward property, 35% (N=251) reported exposure to physical violence, and 5% (N=34) reported receiving armed threats. Demographic and work-related information about the participants is presented in

Table 1.

Table 2 presents the mean±SD scores and internal consistency values for each observed variable (participative safety, support for innovation, relational justice, procedural justice, nurses’ psychological distress, and violent assaults by patients) as well as correlations between the observed variables.

Constructed Structural Equation Models

In the original model (model 1), stress was considered a mediator between organizational justice, collaboration, and patients’ assaults (

Figure 1). That model was rejected because of poor model fit, indicated by significant chi-square values and RMSEA values (90% confidence interval [CI]=.03–.08). The role of stress as a mediating factor was also rejected because stress levels were not dependent to a significant degree on organizational justice, nor were patients’ assaults dependent on stress levels. Therefore, the explanation of assaults in model 1 did not reach statistical significance.

Based on these parameter estimates, we modified the model by removing the mediating factor of stress to achieve better goodness of fit (model 2 in

Figure 1). Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) were used to compare the alternative models (

53). The overall lowest values of AIC and BIC represent the best model fit (

54). The results from the analysis of model 2 indicated a more acceptable model fit on all indices compared with model 1 (RMSEA, CI=.00–.05). AIC and BIC indices were lower in model 2 compared with model 1, also indicating a better fit for model 2. Furthermore, in model 2, relationships between factors were all statistically significant at the .05 level. Organizational justice was positively related to collaboration among nurses, suggesting that low organizational justice is associated with poor collaboration among nurses. Organizational justice was negatively related to assaults, suggesting that lower organizational justice is associated with more frequent assaults. Collaboration was positively related to assaults, which may indicate that better collaboration among nurses is associated with more frequent assaults. However, the correlations between the observed variables related to collaboration (participative safety and support for innovation) and assaults were negative (

Table 2), indicating a negative relationship between collaboration and assaults. The association between collaboration and assaults might be affected by the strong associations between organizational justice and collaboration factors (p≤.001) and between organizational justice factors and assaults (p=.001), which could create a false-positive dependency. Therefore, we may assume that the relationship was negative, rather than positive, indicating that poor collaboration among nurses was associated with more frequent patient assaults. Model 2 explained 5.7% of patient assaults at nearly significant levels (p=.052).

Table 3 shows the goodness-of-fit indices and the coefficient of determination (R

2) for the alternative models for explaining violent assaults by patients.

Discussion

To examine violent assaults by patients on psychiatric wards, we hypothesized that nurses’ stress was a mediator between other model factors (organizational justice and collaboration among nurses) and patient violent assaults, and we developed a model to test that hypothesis. However, stress was not related either to violent assaults by patients or to organizational justice, and therefore the mediating role of stress was not supported.

Although we are unaware of studies that are highly similar to ours, we assume that our results, surprisingly, are not likely to be in line with those of earlier studies. For example, in a cross-sectional study conducted among workers in the Italian public health care sector, indications were found that psychological disorders among staff, measured by the same questionnaire as used in our study, preceded certain types of violence toward staff (

15). However, the study population, consisting of all professionals working in any specialty in the public health care sector, differed greatly from our study population, comprising only nurses working on psychiatric wards.

The very nature of the work performed by psychiatric nurses may explain the contradictory study results. For example, one study reported that nurses’ mental health status, as measured by the GHQ-12, was not associated with patient violence in psychiatric settings, whereas such an association was found in other settings (

29). There may be several reasons for this discrepancy. It can be assumed, for example, that psychiatric nurses are more accustomed to dealing with aggressive patients compared with nurses in other medical fields. Also, the behavior of psychiatric nurses may not be as strongly affected by stress compared with that of nurses working in other specialties.

It is also possible that the instrument used in this study did not capture the dimensions of stress that have been previously documented to be associated with violence. For example, the Italian cross-sectional study found certain aspects of stress, such as job demands and poor workplace social support, as defined in Karasek’s model (

55), to be risk factors for violence (

15). These types of stress—increased job demands (

15) and pressures (

14) and lack of support in the workplace (

15)—were not captured by the measure of psychological distress used in our study.

Our results regarding the association of poor collaboration among nurses and patient violence are in line not only with those of the Italian cross-sectional study concerning workplace support (

15) but also with other findings (

8,

9). Quality of teamwork (

9) and workplace interpersonal relationships (

8) have also been associated with violence. Good collaboration among nurses may have a positive effect on the team’s ability to respond to violence and may add to an overall atmosphere of calm on the ward, which may reduce patient aggression.

Our findings regarding an association between lower perceptions of organizational justice by nurses and increased patient assaults are in accordance with those of an earlier study (

15). However, the mechanisms remain unknown. Research has shown that perceptions of low justice negatively affect workers’ behavior in groups (

25) and increase intragroup conflicts among nurses (

24). Therefore, we could draw the tentative conclusion that low justice perceptions not only may negatively affect nurses’ behavior toward colleagues but also may contribute to poor staff-patient interactions and alter nurses’ behavior toward patients, which may be associated with increased patient assaults (

18).

This study had limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prevents us from making causal statements about the results. The fact that patient assaults were evaluated retrospectively, whereas other model variables were based on nurses’ current experiences, may have resulted in a reversal of the direction of causality proposed in the hypothesized model (for example, increased assaults may predict poor collaboration and low organizational justice rather than vice versa). Therefore, longitudinal research is needed to evaluate the impact of organizational justice and collaboration on patient assaults.

Second, relying on nurses’ retrospective recall of assaults may have caused some misclassifications. Staff may overestimate the frequency of assaults, for example, although other assessment methods—such as daily staff reports, standard instruments, and official incident reports (

56–

58)—may underreport assaults, irrespective of the severity of the assault (

56). Staff may consider assaults part of their job (

59) or feel embarrassed about being assaulted (

60), which may increase underreporting. It has been suggested that self-reporting methods that rely on memory, like other types of assessment methods, are likely to underestimate the occurrence of assaults (

61). However, the validity of our measurement for assessing the occurrence of assaults is supported by earlier studies that have found an increasing risk of self-reported physical assaults connected to patient overcrowding, a risk of violence in psychiatric settings (

11), and an exceptionally high risk of exposure to mental abuse and physical violence among special education teachers compared with their colleagues in general education (

62). In addition, the occurrence of aggression found in this study is quite similar to the findings of earlier studies (

28,

63).

Third, the model explained only a small amount of the variance in patient assaults, which might raise questions about the significance of the findings. However, we had no information on the most important predictors of aggression, such as patient characteristics or severity of the disease. Thus it is to be expected that the model would explain a small amount of variance in patient assaults. It should be noted that the associations between model factors were statistically significant. Thus the study contributed to the understanding of the phenomenon of patient violence toward psychiatric nursing staff, even though its purpose was not to make precise predictions about the role of various factors in assaults by patients.

Conclusions

Nurses’ perceptions of poor organizational justice and poor collaboration among nurses were found to be linked to increased patient assaults, whereas nurses’ stress, as measured by psychological distress, was not linked to increased patient assaults. Longitudinal research is needed to verify our findings and determine the direction of causality. Also, future research should attempt to clarify the mechanisms underlying the associations between nurses’ work-related stress and patient assaults in the context of psychiatric nursing, especially the aspects of stress that may increase the risk of assaults. In addition, the mechanisms underlying the association between nurses’ perceptions of organizational justice and patient aggression must be clarified.

Our findings suggest that evaluating a variety of factors, including organizational justice and collaboration-related issues, both on the frontline and at the administrative level, is important in minimizing patient assaults in psychiatric settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jaana Pentti, B.Sc., for preparing the data for analysis and Jouko Katajisto, M.Sc., for conducting the data analysis.